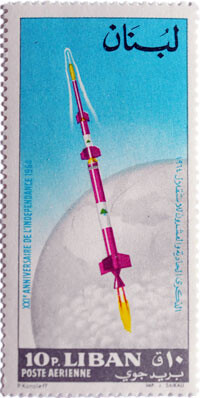

It begins with an image we discover in a book.1 The image is of a stamp with a rocket on it. The rocket bears the colors of the Lebanese flag—an image we don’t recognize, we don’t understand. It does not belong to our imaginary.

What does it show—a weapon, a missile, a rocket for space exploration? Is it serious or just a fantasy? Did the Lebanese really dream of participating in the conquest of space? It’s hard to believe and rather surreal. We ask our parents, our friends … No one remembers anything, no one knows what we’re talking about.

It is 2009 and we begin our research. A web search for “Lebanese rocket” yields only images of war, specifically Hezbollah missiles targeting Israel and Israeli missiles targeting Lebanon. When we search for “rocket” or “conquest of space,” we find many images, but no trace of our Lebanese rocket. But we do find some useful information.

The adventure began in the early 1960s, when a group of students from Haigazian University in Beirut, led by their mathematics professor Manoug Manougian, designed and launched rockets into the Lebanese sky. They produced the first rocket in the region. While the United States was preparing to send its first Apollo rocket into space, while the USSR was on the verge of launching the first manned spaceflight, Manougian and his students began their research on rocket propulsion. A crazy challenge for a tiny country!

We go through the daily newspapers from that period. At first, we find very few details about Manougian’s rocket research, except for the dates on which his rockets were launched. More than ten rockets were launched, each one more powerful than the last; their range increased from 12 kilometers to 450 and even 600 kilometers, reaching the stratosphere. The state and the army helped with logistics and financing and provided the scientists with a permanent launching base in Dbayeh. The Lebanese Rocket Society was born. A stamp—the very one we had seen—was issued to celebrate the event on the occasion of independence day in 1964.

It was a scientific project, not a military one. Manoug and his students wanted to be part of the scientific research going on at the time, when the great powers were vying for the conquest of space. The period from 1960 to 1967 (when the Lebanese space project came to an end) was considered by many to be a time of revolutions, with the possible alternative offered by the pan-Arabism of Egyptian President Abdel Nasser, before the Arab defeat in the 1967 war. Lebanon was just emerging from a civil conflict between Nasserists and pro-Western groups, which in 1958 had led to the landing of 15,000 Marines to support the latter. When elected President, General Fouad Chehab needed to bring society together under a strong and centralized state, which made the space project convenient for the political interests of the time. This made for two opposing strategies: On the one hand, the state could use the project as a symbol for its army, which hoped to weaponize the project. On the other hand, the scientists from Haigazian University, mainly Armenians who came to Lebanon from all over the Arab world (Palestine, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and so on—Manougian himself was born and grew up in Jerusalem) were convinced that only through research and education could peace be built.

Strangely, this project has totally disappeared from individual and collective memory. No one really remembers it. There is no trace of it in our imaginary. This absence surprised us. It was like a secret, a hidden, forgotten story. As artists who have built a great part of our work on stories buried or otherwise kept secret, we were interested in this type of narrative and the way it resisted the dominant imaginary.

With this, we began doing in-depth research and making a film on the Lebanese Rocket Society.

1. The Unrealized Imaginary

The representations of the rockets do not call on any imaginary of our past. Is this gap in our imaginary due to an absence of images of the rockets?

In Beirut, we find an album of photos by Edouard Tamérian that the members of the Lebanese Rocket Society offered to President Chehab. At Haigazian University, where the project was born, we find a few images, and then we find a few more at the Arab Image Foundation. There are about ten altogether. They were taken by photographers Assad Jradi and Harry Koundakjian. Both photographers lost their negatives during the Lebanese Civil War. Jradi lost his in 1982; when Israel invaded Lebanon, his brothers got scared and burned the negatives. Koundakjian lost his when a bomb fell on the Associated Press offices where he kept his images.

When we meet Assad Jradi, he tells us something we find quite interesting: during the civil war, all the photos he took were out of focus. He didn’t understand it, he still doesn’t understand it: he couldn’t capture clear images—the outlines, the features were all blurred. This immediately reminds us of a text by writer and artist Jalal Toufic, who asserts that during a war, the images taken are necessarily out of focus. The photographer is subject to imminent danger, has little time to focus, and his compositions are erratic. His images are nearly always blurred by the speed of war. After the war, the fuzziness still present in the images is due to the withdrawal of what is photographed, which is no longer there to be seen. Toufic argues that, because of this withdrawal, part of the referent cannot be precisely located, whether in matters of framing, of focusing, or both.

This is also what we have focused on in our own research: referents that cannot be located.

We begin to work on the film, using as a starting point the absence of images. But very soon the situation changes. We end up finding images of the Lebanese rockets in Tampa, Florida, with Manoug Manougian, the professor who started the project before leaving Lebanon, never to return to the region again. From the smallest to the largest rocket—from Cedar 1 to Cedar 8—Manoug kept all the films and photo archives! He saved everything for over fifty years.

Even when we see these images, we do not completely recognize them. The history of that period was written without them, maybe because most of the witnesses—those who participated in the project—left Lebanon and are scattered all over the world.

This may also be a consequence of the Lebanese Civil Wars, which took with them memories of the past. Or even before that, it may be a consequence of the June 1967 War between the Israeli and Arab armies. When the space program was halted definitively and suddenly sometime after the 1967 war, it was the end of a certain idea of the Pan-Arab project that was supposed to unite the region and inspire people to shape their own destiny. The end of this project shattered an alternative vision, a progressive and modernist utopia that promised to transform our region and the world. Such is the phantasm that we have inherited from the ‘60s, and even if we refuse any kind of nostalgia or idealized link to it, it keeps haunting us. Our research on the space project is in a way a reflection on those years and those mythologies that changed after the war of ‘67.

But maybe what has changed the most is the image of ourselves, of our dreams. We just can’t imagine ourselves having undertaken a project like the Lebanese Rocket Society. But while that imaginary has withdrawn, perhaps telling the story could enable the photographs and documents to somehow bring it back. It is what we attempt to do in the first part of our film. And as the narrative unfolds, we ask ourselves: How were we able to totally forget this story?

2. Different Reconstitutions

It is not the first time we have faced oblivion and invisibility. They were what first prodded us to make images in the aftermath of the Lebanese Civil Wars. Artists of our generation have often investigated the writing of history and the difficulty of sharing it.

For certain cultures, permanency stems from the act of redoing, destroying, and reconstructing. But in a country that has preferred amnesia, what does it mean to save traces, archives? If we need history, how can it be written without our being mesmerized by memory, whether individual or collective? How to think about history, about its manipulation, its rewriting, its function, while trying to understand which representation of ourselves we choose, or which we allow to be chosen for us?

What is left of the space project today? No commemorative stone or monument relates the adventure of the rockets. Facing this absence, how can this story be told in the present? What would it mean today to think about this forgotten story and reconstitute part of it? What does it mean to reproduce the gestures of the past today?

Issues of reconstitution and reenactment can be said to go way back in our lives, before even our practice and research. In 1922, Joana’s paternal grandfather and his family were thrown out of the city of Izmir by the Turkish army. They took refuge in Lebanon, having lost everything, including the contents of a safe holding the dowry of Stephanie, the mother of her grandfather. At first they lived in real misery, and her grandfather furiously tried to recover the family estate and the contents of the safe. When negotiations with the Turkish government proved successful and the safe was finally opened, there turned out to be a big hole in the back. Its contents had been stolen.

Joana’s grandfather then rented a safe in a Lebanese bank and began, with great determination, to reconstitute his mother’s dowry. It took his whole life: from the two silk handkerchiefs, to the drachmas and rubles, to the diamond ring and bonds. Nevermind if some of the currencies had lost their value, everything had to be exactly as it was before. This is the original instance of reconstitution Joana observed, and it gave her much food for thought.

In 1999, while shooting a film on the Khiam detention camp, those questions of reconstitution arose in a very practical manner: The camp of Khiam, located in the area occupied by Israel and the army of South Lebanon, was a camp about which much was heard but no image was ever seen. There was a kind of impossibility of representation. We met and filmed six detainees who had been recently freed. Through their testimony, the film is a kind of narrative experimentation, an exploration of the way the image, through speech, can be built progressively on the principles of evocation; this work echoes a long reflection on latency that we have been carrying out.

In the film Sonia, Afif, Soha, Rajae, Kifah, and Neeman, who spent about ten years in detention, recall the camp and narrate how they managed to survive, and to resist, through the creation and the clandestine production of a needle, a pencil, a string of beads, a chess game, and a sculpture. Faced with a total lack of elementary and necessary objects, the detainees developed and exchanged astonishing artistic production techniques. When we met them, most of them wanted to demonstrate how they made these objects. They wanted to reproduce their gestures in front of the camera, to recreate the objects for us. We had very long discussions on the subject: the gestures they had made, in spite of fear and torture, arose in the camp from their rage, their will to survive, to disobey, to preserve their humanity. Spending hours rubbing olive stones against the wall and getting bloody fingers trying to pierce them—how can one reproduce that?

Very soon, their gestures appeared, in our eyes and in theirs, as fake, out of context, just the opposite of what they were trying to convey to us. Reconstitution seemed impossible. Only speech could really evoke all this, underline its strength. When the camp was dismantled in May 2000, it was possible, at last, to go to Khiam. The camp was later turned into a museum. However, during the war of 2006, it was totally destroyed by the Israeli army. Faced with ruins, there was a debate about rebuilding the camp as it had been. But is it possible to reconstitute a detention camp? What would that mean? And if it’s not possible to reconstitute the camp, how to keep a trace of it?

In 2007, we again filmed the six detainees we had met in 1999. We asked them to react to the destruction of the camp and also to its possible reconstitution. They shared with us their reflections about memory, history, reconstitution, and imagination. They seemed to us somehow defeated. With the liberation of South Lebanon and the dismantling of the camp, the “winners” of the moment had no real consideration for them. The history of the camp was being rewritten without them. In the film, many of the former detainees mention the Ansar camp, which was much larger than Khiam, and which was also demolished. Today, on the site of the Ansar camp there is a restaurant, an amusement park, a swimming pool, and even a zoo.

The former detainees mention this camp as if they feared that Khiam would someday also be forgotten. It is a question of the trace, of the monument, of reconstitution. But how does one proceed? Can we rely on our memories, our perception? How can transmission occur? How to ensure the transmission of testimonies when faced with the impossibility of reconstitution and the danger of disappearance?

When, in 2001, Jalal Toufic asked us to comment on our work for a special edition of the magazine Al Adab, we simulated an interview with Pierre Ménard, a fictitious character create by Jorge Luis Borges. In Borges’ short story “Pierre Ménard, Author of Don Quixote,” Ménard wants to rewrite identically the famous novel by Cervantes, but without merely copying it. Rather, he wants to place himself in the same writing conditions as Cervantes in order to find the original process which gave birth to the novel. Borges describes this whimsical and surreal work as philosophical proof of the superior, nearly overwhelming power of the historic and social context that surrounds a literary work.

In the interview, Pierre Ménard criticized us for burning, in our project Wonder Beirut, postcards of the ‘60s. The burning was meant to imitate the destruction of the real buildings depicted in the postcards by bombings and street battles. Pierre Ménard said:

We had spoken about them and I had keenly advised you to do a literal version of the literal version, a literal photograph of the literal photograph. To photograph anew these postcards, yes, I do agree! But why burn them? You could have stopped just before that.

I have here two images, one taken by the photographer in 1969, the other of this same postcard, dated 1998. Even if the photographs, as you say, are basically identical, the picture from 1998 is infinitely richer and subtler than the original photograph from 1969. It is amazing.

By simply photographing these images you invented a new path, that of deliberate anachronism and wrong techniques.

To simply reproduce them in 1998 would have been a revelation. To burn them is an understatement that weakens the strength and the power of the work.

In Pierre Ménard’s opinion, redoing a gesture is never redoing it. It is doing it for the first time. It is like ecmnesia, the emergence of old memories, of the past relived as a contemporary experience. It is like dejà vu, this false temporal recognition due to a confusion between the present situation and a similar but not identical one in the past.

3. A Trace of a Trace: The Reconstitution of the Rocket Cedar 4

Faced with the absence of any record of the adventure of the Lebanese rockets, we feel the desire to rethink it in the present. While we are working on the film, we have the idea of redoing these gestures in the form of various art installations.

The first one consists in producing and offering to Haigazian University, where the project began, a scale reproduction of the Cedar 4 rocket, eight meters long and weighing a ton. The rocket is built in a factory in Dbayeh, mounted on a truck, and then transported through the streets of Beirut to Haigazian University. In doing this, we try to combat a narrowing of significations and of our territory. Those rockets were first devised in a Protestant university, directed by a reverend dean who considered this research a gesture of peace through education. Nowadays, the same object is synonymous with war and perceived only as a missile—knowing of course that missiles and weapons are a major political topic in Lebanon. Doing this is also an affirmation that this is not a weapon but the result of the research of a group of dreamers and scientists. And it’s here, on the campus of the university, on this territory, that it will be recognized for what it is: an artistic and scientific project.

Furthermore, making a sculpture as a tribute to the project and those dreamers means giving a materiality to that absent imaginary. It also means questioning the possibility of a “monument” (with all its connotations) to science, insofar as our society has very few unifying elements, little shared history, and many community or sectarian monuments erected by micro-powers. It also means overcoming the nostalgia for what used to be, the regret over what could not be achieved. We attempt to tell the story, to extend the gesture of the Lebanese Rocket Society into the present, to activate the chain of transmission. It means somehow respecting the archives when narrating this story, and at the same time eluding their excessive authority, as well as the charm of the photographic process. It is essential to avoid fetishizing the image. What is at stake is not conformity to an original. The gesture does not refer to the past. The gesture recalls it, but happens in the present, reaching for the possibility of conquering a new imaginary. To question this process, we tried to restage, to relaunch the rocket itself.

We remembered a discussion we had with the photographer Assad Jradi. Looking at one of his images, Assad believed that he had screwed up the photo and he was furious: he photographed only the trace of a rocket, a spoiled, unusable photo. We disagreed and said that we loved the photo, which we considered highly artistic. He looked dubious. There lies the difference between the document, its producer, and its use: to us, the image was artistic, while to Assad, it was rubbish. This gap expresses the transfer of the very stakes of the image. In our view, this image was a trace, the trace of a trace. It gave us the idea to replay what had been played.

Once again we requested the authorizations—about ten of them—to parade the rocket through town, but instead of moving the entire rocket, we transported, six months later, its cardboard outline in two pieces. We no longer feared being arrested or bombed, or causing an accident or a drama. We went along the same route, with the same convoy, to block the streets and attempt a photographic experience.

With the help of two other photographers with a digital cameras, and with our own argentic camera, we were to photograph the rocket passing through the frame during the time exposure of the photo, which meant that the photo depended on the speed of the convoy, the distance traveled, and the distance at which we stood from the moving convoy. Such an experience can only be carried out through repetition; various tests had to be conducted, many attempts for each image, starting all over again, blocking the streets, the highway, sending the convoy through once more until we found the right speed both for the truck and the camera shutter.

Since the outline of the rocket was white, the streaks behind it were ghostly, like the trace of a trace. This led to the Restaged series, a photographic reenactment of the event of transporting the rocket. These gestures of rebuilding the rocket and restaging its passage through the city differ from a traditional reenactment. In a traditional reenactment, you do again something that has already been done. Usually, the purpose is to relive important moments in history, to bring back to life and transmit a historic heritage. Reenactment of this sort has a pedagogic and an illustrative aspect, as seen in common practices of recalling and recording social history. Usually it is based on communication strategies. An established power would like to make it known that a certain event occurred, and resorts to theatrical form. What we are talking about is different. The notion of reenactment we are working with is not a representation or an investigation of a past event in order to better understand it. It is not a repetition or an illustration. Rather, it is an experience: it consists in introducing an element from the past into today’s reality and seeing what happens.

4. Between Reenactment and Reenaction: On Ruptures, Past, Present, and Science Fiction

In the preface to The Crisis of Culture, Hannah Arendt defines the notion of breach as the moment of rupture in which man, caught between past and future, is compelled to project himself into an uncertain future, and therefore into the possibility of starting something new, of inventing himself in uncertainty. Arendt begins her article by quoting René Char: “No testament ever preceded our heritage.” This aphorism testifies to the abyss created after the Second World War. Arendt describes a situation that is “at odds with tradition.” Work, or more precisely action, should not attempt to link both. It is not a question of reviving a tradition or inventing a replacement to fill the breach between the past and the future. This very breach is at the heart of our vision of reenactment, facing a rupture which at the same time questions the relation between two worlds, between a past and a future.

The point, therefore, is to invoke a story to be able to reconfigure, to reinvent ourselves, and at the same time to experiment, to perform in the present, in doubt and uncertainty. Rather than reenactment, we should call it “reenaction,” like an experiment, a restaging, a restart. In our work as filmmakers, we assemble the elements and let things happen, hoping something unusual will arise. Reenaction is doing something that has already occurred, but for the first time, such as repeating a gesture that did not originally registered in the collective consciousness. The traditional definition of reenactment—“do once more in the present what occurred in the past”—could be replaced by “do for the first time something that already occurred.” This brings us back to Pierre Ménard.

What is required is not to communicate but to experiment, to discover, to search without knowing the ultimate result. The possibility of failure always exists. Above all it is a matter of experience but also of negotiating with reality, within reality, aiming at creating new situations, new contexts, new meanings. Such an experiment is a sort of resistance to existing powers, a strategy of opposition and contestation.

What is performed in the Lebanese Rocket Society is the gesture of dreamers, the will to push against limits, to consider that science and art are the place of this possibility. In such a case, the rocket appears no longer as an object of war but refers to a scientific and artistic project. Such an action should not be a collective one that could be seen as an instrument of patriotism or nationalism. It is a personal and singular experience, an individual effort, a singularity which attempts to reconfigure and link itself to history. It does not stem from a place of power or of knowledge, from a place of certainties, but rather from a place of doubts in the face of the unknown and the future. It is also a recognition of filiation, a tribute.

This is what we try to get at in the installation The Golden Record. Starting in 1962, the Lebanese Rocket Society began installing in the heads of the Cedar rockets a radio transmitter, which broadcast the message “Long live Lebanon.” This reminded us of the American space exploration missions, such as Voyager 1 and 2, which carried on board a gold-plated copper disk as well as a cell and a needle to read it. Engraved on the disk were sounds selected to draw a portrait of the diversity of life, history, and culture on earth, a message of peace and liberty, a “bottle thrown into the sea of interstellar space”.

We wondered how we could represent that period of the ‘60s through sound. This led to the creation of “The Golden Record of the Lebanese Rocket Society,” a soundtrack created from sound archives of the ‘60s, based on the memories of the various members of the Lebanese Rocket Society. It is a portrait and a sound representation of Beirut and the world in the ‘60s. “The Golden Record” is at the heart of the animated film that ends our documentary on the Lebanese Rocket Society. The uchronia we developed with Ghassan Halwani imagines a Lebanon in 2025 where the space project did not cease in 1967. Strangely, in the Arab world there are very few science fiction works that imagine the future, not only in cinema but also in literature.

These various tributes to dreamers are individual attempts to, as Hannah Arendt says it, move in this breach between past and future. Like a game of reference and historical crossings … That is maybe where history, past, present, but also science fiction and anticipation, can be questioned, where we can project ourselves into a future, even an uncertain one.

The book was Vehicles, edited by Akram Zaatari and published by the Arab Image Foundation and Mind The Gap.