Nowadays, artists’ voices are thought to be important in giving shape to society, and art is considered to be useful. Moreover, the state, the private sector and society attribute to art a decisive political role as on the one hand, they invest in culture with the purpose generating political and economic surplus value. On the other hand, art and cultural practices are now part of the same network of strategies and questions as social movements are (this space is known as the “Infosphere”). In a context in which the creative, political, and mediatic fields are intrinsically linked, contemporary cultural practices point toward a new social order in which art has merged with life, privileging lived experience, collective communication and performative politics. In turn, the commodification of culture and its use as a resource—as well as the fusion of art, politics, and media—have had a significant impact in the way in which capitalist economies operate. A consequence has been the predominance of immaterial or cognitive labor over industrial production. Not to say that industrial production has ceased to exist, on the contrary, it has increased more than ever and for the most part it has been transferred to third-world countries. The prevalence of cognitive or immaterial work in contemporary capitalism implies that the main source of surplus value is the production and dissemination of signs. In other words,“creative’ work” has been injected to all areas of economic life. Immaterial labor also means the production of social life as lifestyles, and forms of life—a new form of the common at the center of which culture is located.1

In this context, the production of contemporary art, as Brian Kuan Wood and Anton Vidokle pointed out, has been foreclosed by a network of protocols dictating the forms and means of production of art circulating in exhibitions, galleries, biennials, and fairs. And while artists may address exhibition politics as a theme in their work, they are limited in terms of producing something outside of the consensual barriers placed on exhibition politics. This is due to the existence of a systemic enclosure which extends well beyond the consensus of the art world: art is fused with political sensibilities that exploit art’s diplomatic potential, as these political sensibilities consider culture to be a form of social capital, a resource. Thus, a lot of money is put into play.2 Under these conditions, is there any room left for autonomous, committed art?3

1. Politicized Contemporary Art

When considering the relationship between contemporary art and politics, it is simply assumed that art, in one way or another, can serve as a catalyst for political action or participation, as it can reveal capitalism’s “hidden” contradictions. And while the present is always dark and opaque, art is given the task of teaching us how to see or perceive things in a different way—it is considered to be training, an act of observation or exegesis. Recent exhibitions and biennials address questions that are perceived to be “political,” for example: labor, poverty, exploitation, violence, globalization, war, and exclusion.

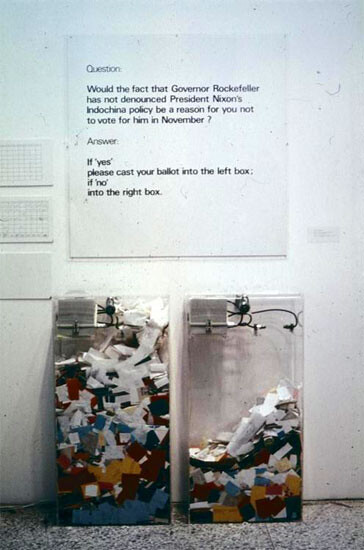

Examples of recent exhibitions in Mexico whose titles underscore the politicization of their content include “For the Love of Dissent” and “Exercises of Resistance” (MUAC, 2012), “The Redeeming Institution” (SAPS, 2012), and “Resisting the Present” (Amparo Museum-Puebla, 2011). Last year, two exhibitions at the Modern Art and Digital Cultural Center Estela de Luz addressed the way power interferes with the flows of information and representational codes, as well as the blurring distinctions between art, action, social movements, media, and semiotic ownership. On an international level, we had Manifesta 9 in Genk, Belgium, the European biennial for young European art curated by Cuauhtémoc Medina entitled: “The Deep of the Modern.” The exhibition deals with the political and economical history of the city of Genk from the point of view of the heritage of its coal mines. The works in the show address the realities of the coal miners’ work, the production and business of coal mining—as well as, include an iconographic study of coal in modern art and a display of mining paraphernalia. The politicized nature of this exhibition was justified by Walter Benjamin’s dialectic materialism, insofar as the exhibition incorporated material traces of Genk’s industrial past in order to renegotiate them in the present day. In this case, the art shown illustrates a curatorial framework that signals the conditions and relations of the production of a specific historical moment—the age of industrial capitalism. Another example from last summer is the Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, which invited the Occupy movement to participate and camp out in the show’s most important site (Kunstwerke). A small group, also related to the Occupy movement, was welcomed by dOCUMENTA curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev after the group set up outside the Fridericianum. Occupy interventions borrowed techniques and tactics from contemporary art and offered a participatory, anti-elitist4cultural practice, as indicated by one of the signs hung by Occupy members in one of the Kunstwerke showrooms: “This is not our museum, this is your action space.”

Linked to the Occupy movement in terms of similar politics, there is also what has been termed “semi-autonomous” art, a manifestation that goes beyond the confines of studio practices to focus on being active in the social field. Artists working on this vein, follow an ethic of action and commitment outside of the artworld, seeking to intervene in urgent issues in the public sphere, with all its complexity. Traces of these manifestations are occasionally exhibited in museums or conducted within the framework of other cultural institutions. This melding of art and life presents new forms of collective civic experience and is based on communication and exchange. It is known as “relational art,” “participatory art,” “community art,” or “socially engaged art,” among other names. According to Claire Bishop, socially engaged art opposes, in principle, political and aesthetic “spectacles,” favoring social participation as a guiding strategy. Beginning with the premise that “contemporary capitalism produces passive subjects with very little agency or empowerment,”5 participatory seek to stimulate the public and turn them away from the passive, private consumption of spectacle in favor of creating a shared space for collective social engagement through constructive or symbolic gestures that have social impact and create new alternatives.6 These works propose solutions for short term improvement, unlike more traditionally politicized art that opposes the status quo and reveals contradictory social truths.

The past decade consolidated an alliance in the field of cultural production between the states, corporations, the art market, and private sector.enterprise. In this context, the politicization of art may imply can involve the search for openings in order to affirm the (rapidly dwindling) public character of cultural institutions defending their autonomy (which they don’t really have) from the marketplace and from corporate patrons.7 An heir to what’s known as “Institutional Critique,” we have, for example, a recent project by visual artist Jonathan Hernández, which was vetoed by the head of the Tamayo Museum in Mexico City. Hernández’s proposed contribution to “First Act” (2012) consisted of making available to the general public information about the Museum’s remodeling costs and of the exhibition production budgets. Blurring the line between civic duty (demanding transparency) and institutional critique (revealing the hegemonic interests behind the politics of the museum’s exhibitions), interventions of this kind seek to exacerbate the tensions between institutions, public opinion, and the art world at large.

2. Contemporary Art and the Democratization of Culture

Being “contemporary,” art exists in the same temporal space as culture and has therefore been integrated into it. Culture is the social process through which we communicate meaning in order to understand the world, build identities, and define our values and beliefs. In the late 1990s, theorist Fredric Jameson argued that the social space was completely saturated with the image of culture.8 This is because in our professional and daily activities, as well as in the various forms of entertainment we enjoy, society consumes cultural products all the time. This characterizes the postmodern “cultural turn” diagnosed by Jameson, which was further elaborated by George Yúdice upon observing (in 2003) that the uses of culture had undergone an unprecedented expansion not just in the marketplace but also along social, political, and economic lines. According to Yúdice, since the states and corporations already utilize culture as a tool as they search for economic and sociopolitical betterment—for instance,in peacefully resolving violence and crime, reconstructing the social fabric, transforming society, creating jobs, increasing civic participation, and so forth—culture has become a resource.9 In Mexico, for example, one of the priorities of the National Action Party (PAN) was “the development and democratization of culture.” The government invested an unprecedented amount of money in producing, disseminating, and managing culture, inviting and even facilitating the participation of corporate and private sponsors, collaborating with the art market by investing in the Zona MACO art fair, and in general implementing an official program to guide the symbolic development and satisfy the demand for cultural and creative assets.10

The notion of “democratizing culture” is inspired by the definition of culture set forth by the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. According to this declaration, culture plays a crucial role in social and economic development, since the cultural and creative industries generate jobs and income and attract investment.11 The directives of the global consensus on the functionality of culture as a democratizing entity establish a link between cultural freedom, cultural promotion, and democracy, with the goal of expanding individual choices, encouraging the active participation of the people, respecting other cultures, promoting the freedom to choose one’s own identity (and to respect the identity of others), and so forth. Despite the high expectations we might have regarding the value of culture, however, the effects and benefits of showing politicized art and organizing cultural discussions and exchanges are unpredictable.

The relationship between the cultural and political spheres (that is, the instrumentalization of culture in the name of politics) is nothing new. Yet according to Yúdice, UNESCO’s cultural projects, globalized civil society, governments, NGOs, the market, cultural managers, and those who work in cultural and creative industries have brought about an unprecedented transformation in our understanding of culture and what we do on its behalf.12 This transformation brings up a well-worn contradiction between the trivialization of cultural products to serve the mass consumer market, which is seen as something negative, and the process of cultural democratization, which is seen as something positive. In transcending this contradiction, I am interested in explicating why art (subsumed to the demands of the cultural and creative industries, subsidized by the state, market, and corporations) is considered a privileged field of politicization and even an integral part of political action and voice when it comes to anti-hegemonic practices. What are the implications of this for committed, autonomous art?

3. Art with Political Purpose: Art and Social Movements

In her 1968 essay “The Crisis in Culture,” Hannah Arendt argues that true art has no purpose and is useless and therefore not a part of political action.13 According to Arendt, art and politics are two separate spheres, since political action or “speaking out” necessarily implies means or ends, while art is autonomous and needs no justification. When art has political aims, it becomes propaganda (for example, socialist realism under Stalin’s regime). For Arendt, what art and politics have in common is that both are “carried out”—to use a term posterior to Arendt—in the public sphere. With the advent of industrialized culture, however, once mass society became interested in cultural values and began to monopolize culture for its own ends, transforming cultural values into exchangeable values, a fusion between art and politics occurred in the greater cultural sphere.14 From this moment on, modernism’s political project of transforming the world by means of criticism, subversion, transgression, transformation, and negativity took its place within postmodernism at the very center of society.

The fusion of art and politics in the cultural sphere takes place within the domain of the Infosphere (also referred to as the “media landscape” or the “field of perception”), which can be defined as the layers of communication that comprise the social system. These include the internet, society, culture, means of mass communication, and symbolic and affective regimes. Within the Infosphere, cultural currents flow across cultural space, changing the language and forms of self-representation and the meaning of reality.15 Culture is, therefore, a significant sphere of production that manages to multiply meanings by mobilizing a whole system of overlapping cultural references and generating, on one hand, economic surplus, and on the other, social life—its forms and styles. In the context of the Infosphere, it has been said that political activism implies spreading and sharing the desire to change lifestyles, and that social movements are the vehicles for spreading desires and implementing changes.16

Neoliberal policies tend to erode ways of life. For this reason, contemporary social movements haven’t been triggered by problems of wealth distribution or antagonism between the working and wealthy classes (as was the case in the previous century) but rather by concerns regarding the grammar of forms of life: quality of life, equality, individual self-realization, democracy (participation and transparency when it comes to both the media and the government), human rights, the environment, anti-globalization, security, and so forth.17 With this in mind, Brian Holmes observed that social movements necessarily incorporate a matrix of four convergent elements: art, scientific research and critical theory, media, and politics (self-organization). This implies that social movements are built within society’s cultural sphere. On one hand, creativity and culture lie at the heart of the struggles that social movements engage in, because their primary means are information and communication technology, which are instrumental when it comes to challenging existing power structures and creating alternative means of dialogue. On the other, we have to consider that politics has become a question of epistemology, a means of expression and a technique for making certain topics intelligible—topics which gain relevance the more visible they are in the media and sociopolitical fields, enabling them to mobilize emotions such as fear, insecurity, indignation, and anger. Political work involves not only the creation of new forms of life, but also the modification of what is visible in the Infosphere in order to shape political “forms of consciousness” (adding, deconstructing, denouncing, diverting signs, codifying and decodifying). However, while being “counter-hegemonic,” these interventions favor the power structure. How? On one hand, if we consider Jodi Dean’s a crucial distinction between politics practiced in the Infosphere and politics exercised institutionally. This distinction brings to light the abysmal disconnect between committed criticism and national strategy, between politics as a means of circulating content and politics as official policy. It could even be argued that politics as a means of circulating content benefits the power structure under the logic of repressive tolerance (freedom of expression is a sign of a healthy democracy): messages are contributions to the circulation of content, not actions seeking answers, and the exchange value of messages overtakes their use value.18 On the other hand, in terms similar to those used by Brian Holmes, Chris Kraus suggests that the consequence of fusing art with daily life is that art is the final frontier for vindicating the desire to live differently.19 Nevertheless, conceiving of social movements and politicized art as vehicles for changing forms of life is problematic because it implies the subsumption of social and economic criticism into art criticism in proposing solutions for short-term improvements. It runs the risk of reducing politicized art to a simple beautification program in gentrified neighborhoods, museological factories, and corporate parks. Changing forms of life is not about creating a reality antagonistic to the prevailing one, because it perpetuates the blockage of what could be. To modify forms ways of life instead of building a distinct reality—negating the established way of life, its institutions, its material and intellectual culture, its liberal morality, its forms of work and entertainment—is self-repression. Constructing a reality that differs from the current one, requires opening an enabling channel for society to intervene directly in political matters, the ability to veto the government’s neoliberal plans, and to offer alternatives to the current social orders of exploitation and political and economic exclusion.20 The problem is that the bourgeois state of law and its institutions—which are the pillars supporting prevailing neoliberal economics and ideology—are the sacred cows which remain untouchable. What must be taken into account is that some recent social movements have been fighting to maintain their ways of life—their privileges—rather than to change them.21

4. For a Committed, Autonomous Art

Besides artistic production that is at the center of social movements (along with communication, critical theory, and self-organization, as we have seen), there is autonomous art—that is, art that is not created specifically to serve social movements or causes. More than other forms or expressions (with the possible exception of film and theater), art that is produced for museums or biennials occupies a privileged space of politicization, while simultaneously being intimately linked to neoliberal processes. By this I mean that today art plays the twin roles of compensating and reducing the effects of neoliberalism, while at the same time actively participating in the new forms of predatory economics and geopolitical power distribution, thus contributing to the transition to the New World Order.22 How so? By being at the center of population displacement processes in impoverished urban areas in order to renovate them and generate capital (in other words, gentrification), and by abetting speculation and urban marketing, branding, and cultural engineering. Cultural engineering embodies corporate and government interference in the design and form of living spaces, because it means developing projects with the goal of constructing realities in which culture acts as a fundamental element of innovation, dynamism, and individual and social welfare. For example, culture has been used to revive economically depressed areas, develop educational strategies, and design social spaces. By being present in every corner of the world as an instrument of intervention and improvement—and to promote liberal values—contemporary art also helps normalize neoliberal policies. A recent example of this is the extension of dOCUMENTA (13) to Kabul. In this case, “culture” came before the fighting ceased, before the NGOs and other foreign companies arrived to rebuild and install civil infrastructure, fiber optics, security and surveillance devices, among other things. This sort of thing is possible because cultural expressions are easily integrated into the global panorama of states of emergency, militarized zones, and permanent war, which have become the norm in the early twenty-first century.

When it comes to contemporary art, we must also consider that the bourgeois order that sustains the economy—along with the internal conditions of producing, exhibiting, and consuming art—are strictly taboo: untouchable by even the artists considered most radical.23 This is because contemporary art is a playground for corrupt opportunism, speculation, and manipulation, a place where Darwinian competitiveness has created a work force that will never achieve solidarity.24 In this context, the profile of the artist as an antisocial radical has softened, giving way to a new, affirmative image of an enterprising artist in and of himself, able to solve problems in a nonlinear, creative manner.25 As such, the contemporary artist embodies the figure of the precarious, entrepreneurial worker, the manager of his own human capital, freelancing from project to project. We must also take into account that society disproportionally rewards A-List artists, curators, and other cultural producers in a way not unlike it rewards managers or CEOs of massive corporations, conferring on them direct membership in the new oligarchy.

To conclude, could politicized art, as Hito Steyerl argues, as art that focuses not on what it shows but on what art does and how it does it.26 To paraphrase Jean-Luc Godard, it’s not a question of making political art or film; it’s about making art or film politically. With regard to the politics of the field of art, however, what prevails is the diluted and domesticated version of 1970s institutional critiques—for example, Jonathan Hernández’s rejected piece, or the phrase coined by the Tercerounquinto art collective: “No artist can resist a $50,000 cannon blast,” which was supposedly carved into a wall at the Museo Amparo. Another example is Adriana Lara’s 2006 work Artfilm I: Ever Present—Yet Ignored, which shows several young people meandering through an art gallery while hearing a voiceover reflecting on the conditions of producing contemporary art (it is a consumer’s market, it is not politically effective, artists today are mainly interested in their own emotions). These two works arose through the ironic self-reflexivity of the conditions of producing art, reiterating the predominance of an enlightened false consciousness and propagating the ideology of cynical reason: “they know very well what they are doing, but still, they are doing it.”27It becomes clear that the state of contemporary art is quite different from what gave rise to institutional critique in the 1970s, which was focused on examining the subjection of art to ideological interests.28 Unlike forty years ago, institutions today are more opaque, more exclusive, and they share objectives intrinsically linked to corporate, neoliberal agendas (to the point that those agendas have become invisible). Cultural institutions are the administrative organs of the dominant order, and cultural producers actively contribute to the transmission of free market ideology across all aspects of our lives.29

Therefore, a genuinely radical approach within the field of art would mean going beyond politically correct art—art that’s satisfied with the system of galleries, grants, and markets, and with serving as the government’s official showcase. For example, the exhibition “A partir de mañana: todo” (“From tomorrow: everything”)—which touched on the theme of the subversion of the hegemonic contents of information as a launching pad for emancipation—took place at the Modern Art and Digital Cultural Center Estela de Luz, the controversial monument commemorating the Bicentennial (of the Mexican Independence and Revolution in 2010). The allegedly “politicized” works in the exhibition find themselves perfectly comfortable in the exhibition space hosting them.

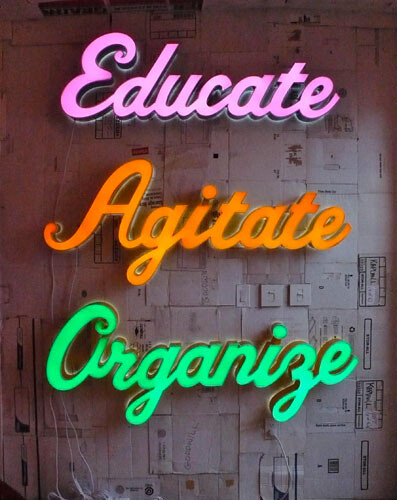

Dissatisfied with competing under the terms laid down by the creative and cultural industries, the production of committed autonomous art would be posited as a precarious working site and would reawaken the hostility between society and culture rather than placating it with pseudo-political products for self-indulgent consumption. It would be an “undemocratic” form of art in that it would not align itself with the neoliberal ideal of political freedom. Addressing everyone, it would release itself from the circulation of content, interrupting it, communicating nothing. It would oppose the visibility of what the system declares as extant (power controls what’s heard and what’s seen, and therefore does not need to employ censorship). Politicized autonomous art would make visible that which does not exist from a different point of view, spreading the contagious attitude of those who have nothing to either gain or lose.

Forms of life unite characteristics that are essential to a particular socioeconomic formation. For example, a form of labor is reflected in a particular form of life. The form of life produced by one’s choices is one’s “lifestyle,” which involves creating one’s own subjectivity by consuming semiotic products.

Anton Vidokle and Brian Kuan Wood, “Breaking the Contract,” e-flux journal 37 (September 2012). See →.

The term “autonomous, committed art” refers to Theodor W. Adorno’s retort to Jean-Paul Sartre’s text on the autonomy and commitment of art in his essay, “What is Literature?” in “What is Literature?” What is Literature? And Other Essays, ed. Steven Ungar (Cambridge Mass. Harvard University Press, 1988) See also: Theodor W. Adorno, “Commitment” (1962) New Left Review I/87-68 (September-December 1974)

Julian Stallabrass, “Art as Radical Camouflage” New Left Review, 77 (September–October 2012)

Claire Bishop, “Participation and Spectacle: Where Are We Now?” in Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991–2001, ed. Nato Thompson (New York and Cambridge: Creative Time and MIT Press, 2012), 34–46.

Ibid.

See Cuauhtémoc Medina, “Camaradas ocultistas, escondidos, opacados (Respuesta de Cuauhtémoc Medina al CIJ),” available online at→.

Fredric Jameson, The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983–1998 (Brooklyn: Verso, 1998), 111.

George Yúdice, The Expediency of Culture: Uses of Culture in the Global Era (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2004).

Everything seems to indicate that Ernesto Peña Nieto’s government will continue with the policies of cultural engineering and management set forth by his predecessor, Felipe Calderón.

See “Plan Nacional de Desarrollo” from the Felipe Calderón government, 2007–2011, 3.8, Objetivo 21. Available online at →.

George Yúdice, The Expediency of Culture: Uses of Culture in the Global Era.

Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought. (New York: Viking Press, 1968), 197–226.

Ibid.

Tiziana Terranova, “Communication Beyond Meaning: On the Cultural Politics of Information,” Social Text 80, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Fall 2004)

Brian Holmes: “Eventwork: The Fourfold Matrix of Contemporary Social Movements,” in Living as Form, ed. Nato Thompson (New York: Creative Time, 2012), 73.

Jürgen Habermas, “New Social Movements” Telos vol. no. 49 (September 1981): 33–37. A project we can evoke here is Tania Bruguera’s “Immigrant Movement International” in Queens, New York and sponsored by Creative Time and the Queens Museum of Art. It consists of a long-term project in the form of a sociopolitical movement initiated by the artist, whose venue is a community space in the largely immigrant neighborhood of Corona, Queens. Bruguera suscribes to the principle of “useful art,” which aims “to transform some spaces in society through art, transcending symbolic representation or metaphor and meeting with their activity some deficits in reality.” A complimentary project is the “Immigrant Party,” which functions as a political party. Bruguera’s problem with action—other than (provocatively) referring to art as merely utilitarian—is that the political formation of both the immigrant and the political party are obsolete forms of political representation. In this sense, I believe that the task that Brian Holmes entrusted to social movements (to propose and implement new forms of life) is more akin to the current historic and socioeconomic moment (though not unproblematic).

Jodi Dean, “Communicative Capitalism: Circulation and the Foreclosure of Politics,” Cultural Politics Vol. 1, Issue 1 (2005): 51–74. Available online at →.

Chris Kraus, Where Art Belongs (New York: Semiotext(e), 2011).

See Raquel Gutiérrez, “The Rhythms of the Pachakuti: Brief Reflections Regarding How We Have Come to Know Emancipatory Struggles and the Significance of the Term Social Emancipation,” South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 111 No.1 (2012): 51–64.

Slavoj Zizek, “Capitalism”, Financial Times, November 2012. Available online at →. We must not, however, underestimate the predominance of “content policy,” an example of which is the use of Twitter during Israel’s recent Gaza operations. The Israeli Defense Forces have a large department dedicated to managing its own online social profiles and monitoring those of Hamas. The war against Gaza last November also took place on Twitter. One minute, the account linked to Hamas, @AlQassamBrigades, announces that it has launched a rocket. Only minutes later, the @IDFSpokesperson responds that it has been intercepted. Thousands (or perhaps millions) sent messages of support, both this way and that. See Verónica Calderón, “La propaganda militar en 140 caracteres,” El País, November 20, 2012. Available online at →.

Hito Steyerl, “Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post-Democracy,” The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: e-flux journal and Sternberg Press, 2012).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Gregory Sholette, “Speaking Clown to Power: Can We Resist the Historic Compromise of Neoliberal Art?” Available online at →.

Slavoj Zizek, “Cynicism as a Form of Ideology” from The Sublime Object of Ideology (London; New York: Verso, 1989) Available online→

Hito Steyerl, “Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post-Democracy.”

Institutional critique in the 1970s involved the politicization of conceptual strategies in order to reveal how institutional interests—mediated by economic and ideological interests—frame and define the production, interpretation, and visual experience of the artistic object. Drawing on theories developed by the Frankfurt School and by poststructuralism, institutional critique examined the subjection of art to ideological interests, recontextualizing aesthetic practices within their own ideological backing, linking social and ideological interests with cultural practices focused on the process of masking and neutralizing culture through “repressive tolerance.” See Benjamin Buchloh, et. al, “1971,” in Art Since 1900 (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2006), 545–549.

See Stephan Dillemuth, Anthony Davies, Jakob Jakobsen, “There is No Alternative: The Future is Self-Organised,” in Art and Social Change: A Critical Reader, ed. Will Bradley and Charles Esche (London: Tate Publishing and Afterall, 2007).

Subject

This text is an indirect reply to Cuauhtémoc Medina in the context of my blog Comité Invisible Jaltenco. See →.