Let all mortal flesh keep silence

and with fear and trembling stand

ponder nothing earthly minded.—“Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence,” Liturgy of St. James1

I was mediated … I was Pop.

—Mike Kelley2

Mike Kelley’s engagement and rupture with popular music began as a teen in Detroit, in the candle-lit gloom of the Catholic Church, with such polyphonic choral chants as the revised fifth-century liturgy “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence.” A piece of music that in “its dark and gloomy quality set the mold for much of my [Kelley’s] future musical interests.” The ancient order of choral music would evolve through popular tongue and secular insertion—French rather than Latin—to threaten, through undulating voice, the Church itself. Thirteenth-century clergyman Jacob of Leige decried this new music and its singers, saying that they “bay like madmen nourished by disorderly and twisted aberrations, they use a harmony alien to nature itself.”3

A papal bull—a charter written by the Pope, in this instance Pope John XXII—issued in 1324 listed the offences of this new music as: “doing violence to words … they intoxicate the ear without satisfying it, they dramatize the text with gestures and, instead of promoting devotion they prevent it by creating a sensuous and innocent atmosphere.” It was musical innovation, the pursuit of vocal polyphony and counterpoint, that threatened the Church and its steadfast plainsong and vocal chant. New compositions relied on secular and vernacular texts in order to employ new vocal devices. Control of the voice and of text slipped away from the Church and toward those wandering singers, those poets on the loose who sang in the marketplace. Among them were the Goliards, clerical students from France, Germany, Spain, Italy, and England who protested the contradictions of the Church, from the Crusades to its financial abuses, expressing themselves through lewd performance, song, and satiric poetry. The Goliards, beloved of English writers such as Samuel Butler and Jonathan Swift—both of whom borrowed their strategies of satirical verse—were, in effect, a literary and spoken-word protest movement. By the fourteenth century, ritual and religious music, its vocalizing and text, had become a popular rather than a clerically aligned form: secular rather than sacred. The earthly mind was pondering, the flesh no longer silent!

The history of ritual, religious, and popular music is one of successive breaks in faith through disrupted form. The Goliards employed satire, reworking Latin texts to prick at the Church and its sacraments. In their ritual and apocryphal “celebration of the ass,” a clothed donkey is led to the chancel during mass. Dancing priests dressed as women sing in the choir and cense the church with the burning soles of old shoes. In response, the congregation is invited to sing a warped version of the Eucharist, a blasphemous “He Haw, Sire Ass, He haw!” The Goliard poets borrowed from church minstrelsy, their mocking, irreverent verses providing a witty commentary on the social and moral climate of medieval Europe. The precursors of modern verse, their bawdy ballads sung in beer halls celebrated the pagan rites of spring and the immemorial urges of the flesh.

Three types of Latin lyric were available to twelfth-century scholar-poets. The first, in honor of the Roman classics, employed the rhetoric of antiquity. The second, a living Christian poetry developed over centuries, employed a new rhythmic and sonorous and often intricate rhyme. The third, the lyric of the Goliards, which employed a tongue dignified by ancient usage, was frequently flippant. Their objects of attack were the Church and its followers—the uncultivated laymen, subject to theological distrust of the body. In short, they produced poetry that offended the pious. Scholars are uncertain whether the name “Goliards” refers to the biblical giant Goliath or to a personification of the sin of gluttony (Gula). Needless to state, these were both derogatory terms used to describe the clerici vagi, the wandering and rebellious scholars of the thirteenth century. Old molds were broken and fresh satiric forms of vocal expression were created. In 1364, medieval ears were opened to the first polyphonic setting of the mass, “La Messe de Nostro Dame,” described by some as the devil’s music. In effect, polyphony—pitch-against-pitch—would lead to the sonic dissonance of noise music. It is in the satiric verse and corrupting voice, in the use of text and performance to attack governing institutions, that we find Mike Kelley, the contemporary Goliard, stinking up the institutions—on occasion the Church itself (Judson Church Horse Dance [2009])—with his version of art, music, and voice as ritual form.

From their lips came sweet sounds.

— Papal decree4

It is helpful perhaps to begin with a key biographical moment, one that will start Kelley on his journey to music: the act of exclusion. Kelley was barred at an early age from music study for the crime of singing with a “bad” voice. As he described it: “There were no music classes, so occasionally students would sing religious or folk songs in a regular class, but I wasn’t allowed to sing because I did not have a harmonious voice.”5 It would be the same when he moved to public school and later to CalArts in order to study with Morton Subotnick: “Because I had no music training, I wasn’t allowed to take music theory courses. So basically, my whole life, whenever I’ve tried to get involved in music, I’ve been institutionally denied.”6 An institutional Catch 22: in order to learn about music, one has to have prior knowledge.

In many ways, Kelley’s relationship to music is formed via negativa; he looks to become what he is institutionally denied and what he is told he has no right to be: a musician. When asked about his musical training in a magazine interview, he responded, “I am more akin to a folk musician, I have no training.”7 Kelley’s experience mirrors the thirteenth-century Church’s fear of choral vocal affect, or the misbehaving “bad” voice that led to a papal decree. The suggestion, in simplified terms, is that “sweet sounds” come from the compliant heart, the gravitas of history—the old texts—and the plainsong. With no recourse to academic musical study, Kelley looks elsewhere: to the musical and visual experimentation of the avant-garde—to the band Destroy All Monsters, a low-budget-sonic-horror that crept from the basement and into the world.

1. Destroy All Monsters

This cacophony of bestial battle was what we were after. We loved the sound of Godzilla’s roar—that backwards-sounding growl with a subliminal tolling bell buried in it, and the sweet cadences of the singing twins who were the consorts of Mothra. That was the dialectic we were after. Those were truly inspiring musics.

—Destroy All Monsters8

This doesn’t come out of music. This comes out of art.

—Destroy All Monsters9

Named after a 1968 Japanese B movie, Destroy All Monsters formed in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1974. The founding members—fellow art students Cary Loren, Niagara (Lynn Rovner), Jim Shaw, and Kelley—met at the University of Michigan. Their shared and heuristically attuned sensibilities resulted in a flowering of the “most obvious popular form: a band.”10 Post-hippy and pre-punk, DAM inherited the end of the utopian dreams of the sixties and served it back in a mocking sonic form that prefigured the Sex Pistols and those punks to come. Harbingers of a coming storm, they were, as Kelley had it, “designed to be a ‘fuck you’ to the prevailing popular culture.”11 In the early to mid-seventies, popular culture and its adherents slumbered to the somnambulant strains of James Taylor and the back-to-nature California dreaming of Neil Young’s Harvest. The failure of the countercultural rock ‘n’ roll project, from Hendrix to the MC5 and its subsequent corporate take-over, left (in America at least) a void waiting to be filled.

Kelley was keenly influenced by the psychedelic compositions and communal band arrangements of Sun Ra, as well as the Brechtian theater of Iggy Pop’s stage persona—two figures who, Kelley states, taught him all he needed to know about art and performance. He also cites the satiric politics of Frank Zappa and the horror drag of Alice Cooper as influences. His early experiences in Detroit—The Stooges, Sun Ra, the Free Jazz movement, and the street politics of John Sinclair’s White Panthers—go some way towards suggesting his formidable DNA.12 It is a lineage that screams pop, so much that it nearly obscures the key influence of avant-garde figures and their thinking, from Russolo to Cage, from performance artists Bob Flanagan and Mike Smith to obscure cult singers and performers like Yma Sumac and Rod, Teri, and the MSR Singers. Kelley’s interests are wide-ranging and necessarily eclectic; they are, as the title of his 1993 Whitney Museum publication has it, catholic in taste.

Rehearsing in Kelley and Shaw’s basement at the Gods Oasis Drive In Church, a hippy commune of sorts where nothing but music was shared. The group recorded many of their sessions on cheap recording equipment; the result was co-released many years later on Thurston Moore’s Ecstatic Peace label and Byron Coley’s Father Yod label. Kelley is one of those rare artists, like his peer John Miller, who wrote extensively about his own work, a practice that owes much to an earlier proto-conceptual generation of artists such as Lawrence Weiner, Dan Graham, Donald Judd, and Robert Smithson. He took it upon himself to counter critical misreadings and to reveal in essay form those minor histories that are otherwise left untold.

Destroy All Monsters was no exception. His decision to pen the facts and frame lost music “to set them up to age” left a map for others to follow. In “To the Throne of Chaos Where The Thin Flutes Pipe Mindlessly,” which accompanies the triple CD release Destroy All Monsters: 1974/77, Kelley gets to the facts of popular music: that with age, those once “potent fuck beats of your prime become limply infantile.” His examples are Cab Calloway who would become the soundtrack of Betty Boop cartoons and Hendrix’s songs transplanted to car commercials: no longer speaking the rhythm of their times, they are caught outside of ritual. What was once relevant is now the Muzak of the ancients. As Kelley states, these are the sad observations of the old, for popular music marches in time with flushed youth: one is in it, part of pops ritual, not observing from a distance. Here we find Kelley in a reflective mood, considering DAM, the band that never was!:

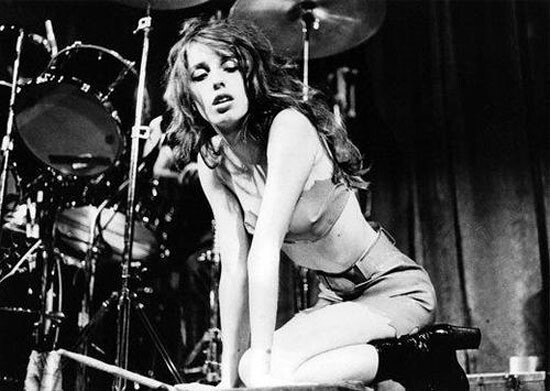

Cary and Niagara would take turns on the various songs. Cary had the better voice: a Jim Morrisonesque low tone, but Niagara was the center of attention. Niagara’s anti-stage presence was captivating. Her emotionless monotone made Nico sound like a screamer, and generally she sang so softly you could barely hear her over the din. Oftentimes she would sing seated, facing away from the audience, and in one memorable show, she lay on the floor in a fetal position with her head on the pillow inside of the bass drum, letting out a pitiful cry every time the bass was struck, yet unwilling, or unable, to get up.13

In DAM’s 2009 triple album reissue Niagara—a sickly anti-blonde Marilyn Monroe with riveting anti-stage presence all cheap peroxide hair and ashen skin—begins her Vampire chant, a declaration of self as folkloric bloodsucker. The lyrics are delivered in faltering style; crawling from the cave of the mouth festering on the tongue this is Karen Carpenter as the living dead hopped up on Valium and Nyquil. The voice is not feminine sweet or controlled, it stands as one of the punk precursors for a generation to come (Ari Up, Siouxsie Sioux). Of these early recordings it is clear that Niagara is the presiding and authored voice, revealed as person as personality: the “I” of the song. To this extent pop rules are exemplified, the “special” and authored voice is adhered to, as listeners we search for the life in someone’s voice that beyond lyrics the material—the tenor of the voice—reveals the person and the body inherent. As the writer Simon Frith has it “the first general point to make about the pop voice, then, is that we hear singers as personally expressive, in a way that a classical singer is not.” The voice in classical music is on par with the instrument it sits within the score and assumes the role of bass, baritone, tenor or soprano. The pop voice fends its way scoreless, feeling, and in this instance crawling it’s way amongst discordant and broken sound. A cover of Mack the Knife is delivered in quavering falsetto the lyrics jumbled, semi-audible and full of laughter accompanied by the ring of a triangle and plodding guitar chords. In the background the band can be heard, laughing, audibly present willing her on, a reminder of the ritual of the band the coming together of people. In Boots Niagara takes on These Boots are Made for Walking. Her vocal delivery floats lazily across a bed of noise, turning this otherwise upbeat song into a choppy psych-rock S&M ballad. Take Me With You, Niagara’s ode to a dead lover buried in a coffin takes a more standard, vocal and guitar approach. To the extent that such songs—few in number—revert to the rock-and-roll call and response of voice and electric guitar, words, their meaning and delivery disrupt happy relations. In You Can’t Kill Kill, deadpan word repetition takes death obsession to new and gloriously melancholic and satiric heights. “No, you can’t kill kill. Because it doesn’t happen twice.”

Kelley’s early work with DAM, its small audiences and generally hostile and room-clearing reception, could be described as of the people rather than for the people. The people in question were Loren, Niagara, Shaw, and Kelley. If popular music form—i.e., the untold rehearsal hours of the garage band—was a process ultimately attuned to its eventual public consumption, then Kelley’s music in rehearsal-as-performance is one that satisfies the moment, the coming-together in discord of like-minded artists: improvisers in the sense of Cornelius Cardew and Free Jazz, more living sonic sculpture than rock ‘n’ roll act. Kelley states, “I am not often that interested in controlling the sounds I make. It is more like play, done for the pure pleasure of experimentation.”14

DAM was an “art school band”—in his writing, Kelley is clear to make the distinction between art school band and the “art rock” of, say Talking Heads, which formed at the Rhode Island School of Design around the same time as DAM and whose format and instrumentation mimicked the standard rock group. DAM’s key instruments were a prepared guitar (courtesy of John Cage) and a drum machine, which the band started using after hearing one on a record by the British band Arthur Brown’s Kingdom Come (for example, on “Time Captives,” the opening track to the album Journey). Alongside drum machine and guitar, Kelley employed various noise-making items, showing the influence he absorbed from the Art Ensemble of Chicago, which employed everything from birdcall whistles to musical toys.

Caught between times, DAM was in the musical no-mans land of the early seventies. Chris Cutler euphemistically describes this period—1969 to 1975—as “the time of the Tiny Flame.” Progressive music was kept alive in this period by the likes of Henry Cow in the UK and Frank Zappa in the US. Kelley and the other members of DAM were too young to be hippies and too old, when it finally arrived, to be punk. It wasn’t until much later that the connections between DAM and bands of similar spirit and intent could be made, and there were many: from New York’s Suicide, to Ohio’s Pere Ubu, to San Francisco’s The Screamers.

In order to consider Kelley’s music, it is first instructive to identify how much his work dealt with and deployed popular form. He embraced the popular, not as skin or simple surface, but as something that speaks meaningfully of the times. In his essay “The Poet As Janitor,” John Miller suggests the a priori motivation and makeup of Kelley the artist as one engaged in class pronouncement. Kelley is seen on the front cover of the catalogue for Catholic Tastes, his Whitney Museum retrospective, literally mopping his way into the gallery. Detroit, where Kelley grew up, was a jewel in the Midwest that over time has seen the highs and lows of the American Dream, from Ford’s Motor City and General Motor’s to riot town, white flight, and righteous race rebellion. This is a history and a city that has provided it’s own soundtrack, from Motown to Detroit Techno—a history that Destroy All Monsters has been retrospectively added to, Kelley and DAM’s voices finally being heard.

2. The Poetics

I consider the work to be an exercise in the construction of a history, and specifically a minor history. Minor histories are ones that have yet found no need to be written. Thus they must find their way into history via forms that already exist, forms that are considered worthy of consideration. Thus minor histories are at first construed to be parasitic.

—Mike Kelley15

In the 1998 book Poetics Project, Kelley and fellow artist Tony Oursler reflect upon the ambitions, germination, and ultimate failure of their joint art-band The Poetics. Kelley’s to-the-point essay title “Introduction to an Essay, Which is in the Form of Liner Notes for a CD Reissue Box Set” reveals a history of a band caught between nightclub comedy act, noise music, and British punk’s landing on American shores. It was a time of border confusion, when for a moment one could move between disciplines, reminiscent of earlier periods when jazz, folk, and psychedelic music were unashamedly linked to the art world and art production.

The Poetics consists of two main releases: Remixes of Recordings 1977–1983, a box set of remixed past material, and Critical Inquiry in Green, an investigation of lost music. The Poetics were also the subject of shows at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo and at Metro Pictures and Lehman Maupin galleries in New York. As Kelley describes it: “The music [of The Poetics] is revealed as not being ‘popular,’ that is, designed to produce instant gratification, since it gratifies fifteen years too late. Instead, it is art, it is façade.”16 At the root of such a statement sits failure, the sense that the music failed in its resolve to reach people. And yet Kelley defines pop music in the basest of terms—as a form that seeks to “produce instant gratification.” It invites the question: Can pop music be both popular and critical?

The birth of The Poetics stemmed in part from the lack of an audience for DAM and the increasing staidness of Ann Arbor. In 1978, Kelley moved to Los Angeles to attend CalArts. The only founding member of DAM that remained was Niagara; with the addition of The Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton, they became what they had initially set out to attack: business-as-usual hard rock. Within a year of moving to LA, Kelley forms The Poetics with Tony Oursler and Don Krieger, both fellow CalArts students. Later they would be joined by artist John Miller.

The name “The Poetics” calls to mind the Aristotle text of the same name, as well as Aristotle’s battle with his tutor of twenty years, Plato, a philosopher who had little time for poetry. Aristotle’s key quote was crucial for the band: “Poetry is finer and more philosophical than history; for poetry expresses the universal, and history only the particular.” It echoes Kelley’s constant battle with history and his place within it. Kelley describes how he encountered the work of Oursler in a crit class screening of Joe, Joe’s Transsexual Brother and Joe’s Woman (1977). Struck by Oursler’s haunting voice and the perverse narratives of his vignettes, Kelley invited him to join the group. Kelley recalls, “I was so impressed with Oursler’s morbid vocal quality and his narrative abilities that I immediately asked him to be the vocalist in the band.”

You come home from work

You turn on the record player

You hear your favorite music, maybe lay down

Close your eyes

You can faaaaaalll into the music

You can feeeeeelll yourself relaxing

Into the music

Parts of your mind you’ve never used before

The power that lies there

Can give you anything—“Listen Carefully,” The Poetics

Your browser does not support the audio element.

Released in 1996 on Kelley’s label Compound Annexe, Remixes of Recordings 1977–1983 presents ninety-one songs over three CDs. No published original exists, putting the fixations of time and place, the “I was there,” in doubt. Are these recordings for real? Who are they made for? They exist outside the ritual ecology of time and place, cargo cult from another time beached upon future shores. “Listen Carefully” establishes the bands relationship to pop music as hypnotic domestic form, evidenced by the scene Oursler describes above. Oursler’s low-voiced “The Loner” treats the plight of the lonely individual as that of the B movie monster, never wanted but occasionally loved by the other strange kid in the class. “Nobody out there likes the loner, but somebody out there loooooves a loner. The loner is sooo … alone.”

In “Searing Gum,” Jim Morrison meets Iggy Pop in Oursler’s aggro-delivery of a song written by conceptual artist and CalArts faculty member David Askevold. Many of the lyrics in the collection take the form of short stories, such as “The New Girl,” in which the archetypal college girl desperate to fit in hosts a party, and things take a turn for the worse, Boone’s Farm wine and all. Bleak shaggy dog stories and abstract jokes meet vocal remonstration, such as in “Rocket #9,” where an indecipherable voice freaks out, making way for high pitched wails accompanied by wood-chimes and trumpet.

Your browser does not support the audio element.

In “The Carnal Plane,” snoring is accompanied by a far-from-heavenly choir of human wolf sounds, animal grunts, and flatulence. Peppered throughout the collection is a series of interviews conducted by Oursler, some of which are set to music; in “Old Hoger,” a young woman describes a séance for a man many had little time for in the flesh, while in “The Little Horn,” Oursler interviews a UFO conspiracy theorist.

“Dream Lover,” recorded for the program Close Radio on KPFK (hosted by artists Paul McCarthy and John Duncan), features Oursler’s loopy demented voice, like something from Walt Disney. “Wait a minute, stop it!” comes a woman’s (Kelley’s) screeched response.

Your browser does not support the audio element.

“Science Fiction” mixes primal language, scat vocals, and reversed vocals. In a similar vein, “An Unusual Bone” features Oursler’s sped up voice, creating a Disney-like character obsessed with an unusual bone constructed from flesh yet unsupported by bone: a reference to the penis, a Throbbing Gristle of another kind. In “Mr. Orgatron,” Oursler converses with an organ: “Hey Mr. Orgatron, how are you doing today? I have a question for you. How come you keep making me play sick things instead of nice peaceful things?” There ensues a call and response between Kelley the organ player, and Oursler the soon to be slaughtered “daughter” of the organ.

Your browser does not support the audio element.

In “Behind the Curtains” the radio detunes between stations while a female voice stuck in in endless loop whispers the title, hinting at something dangerous lurking behind curtained windows. The history of drone music and La Monte Young is taken up in “Tibetan Security Guard,” with its droning vocal croak.

In “Copy Cats” (initially developed as a night-club act) Kelley and Oursler follow the instructions on an educational recording to make farm animal noises, from duck to cow, again in search of the primal. “Wilde Child” finds Oursler in a regressive mode, howling like a child raised by wolves.

Your browser does not support the audio element.

Critical Inquiry in Green (1997) begins with “The Poetics (Initial Inquiry),” an audio questionnaire of sorts: “Have you ever heard any music by The Poetics? Ever seen them perform? What was your general impression of their music? How did it relate to the musical scene of the period? Tell me any experience that concerns a wonderful musical experience?” Voiced by Hollywood actor and Kelley’s neighbor William Wintersole, the questionnaire probes the listener about his or her interest in the band.17 The return of The Poetics, after fourteen years of silence, was for Kelley a critical approach to the repackaging of the history of subcultural musical forms—in short, the historicization of UK and US punk.

Critical Inquiry In Green takes an anthropological approach to the demotic popular voice: the probing questionnaire makes way for the knowledge-imparting lecture-cum-esoteric-sermon, which in turn makes way for the B movie horror voice-over. We are subjected to the voice, to its demand for answers and certainties, yet throughout we are reminded of artifice. By the numbers, “popular” suggests choice and ranking among a limited number of commodities. Production, distribution, and marketing set against “economic-realities,” set against—for want of a better word—profiteering. To this extent, Kelley’s art-bands sit outside the market, within the off-shore currents and experimental sounds that decades later would become pop and “noise.” Kelley bumps against the tautology and apparent binary of avant-experimental vs. folk music—the former a process and struggle for affective aesthetic expression (breaking sonic ground), and the latter predicated on shared histories and a communing with like-minded individuals. He is clear in his definition—seemingly hair-splitting yet crucial—of DAM and The Poetics as “art school bands,” as opposed to the “art rock bands” like Talking Heads and, later, Sonic Youth.

Notably, before becoming a band The Poetics looked to the blend of prop comedy and the high forms of Bauhaus and the Judson Dance Theater; a video playing at Documenta X reconstructed The Poetics’ “Pole Dance,” with two dancers moving around the space, extended poles jutting from their rectum and crotch. Kelley’s crunch of high and low forms informed much of what would come in his EAPR Series and his masterwork Day is Done.

3. Day Is Done

Popular culture’s really invisible, people are oblivious to it, but that’s the culture I live in and that’s the culture people speak. My interest in popular forms wasn’t to glorify them, because I really dislike them in most of the cases. All you can really do now is work with the dominant culture, flay it, rip it apart, reconfigure it!18

—Mike Kelley

Inspired by hundreds of photographs from American high school yearbooks and the holiday pageants, band performances, pep rallies, and Halloween scare parties that they capture, Kelley’s large-scale video installation Day is Done (2005) comprised a series of elaborate vignettes showcasing what Kelley calls “common American performance types.” Each vignette was titled Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction, listed from 1 to the proposed 365 videotapes and installations that would make up the completed final work. First experienced as a fifty-screen video installation at the Gagosian Gallery in New York, Day is Done(Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions #2–#32) was released as a DVD by the film distributor Microcinema International and as an original motion picture soundtrack on Compound Annexe. It’s perhaps one of the first works of art to successfully take on the serial nature of the television drama and the Broadway musical. An anthropological study of American folk culture set largely in an art college—CalArts—Day is Done embodies and spins many popular vocal forms, from Broadway show tunes, choral chants, hip-hop, and metal to R&B and soul. Day is Done signals Kelley’s new approach to popular and subcultural form. No longer something to be celebrated, pop culture is something to be ripped open and satirized. It is also the first time that Kelley has written all of the lyrics.

Drive the train in the tunnel

And around the bend

Put the train in reverse

And drive it in again

Chugga chugga chugga woowoo

Chugga chugga chugga here we go

Engine’s overheated and it’s going to blow!—EAPR#2 (Party Train), Mike Kelley19

Your browser does not support the audio element.

In EAPR#2 (Party Train), three dancers sing and move through the corridors of CalArts: a samba line of black leotards and white face paint, the musical score kept in time by the “chugga chugga” chant of the dancers. In the next sequence, called Candle-Lighting Ceremony, a plump Catholic girl in pigtails calls to the assembled crowd: “I was picked from all my peers to light this light, to allay your fears, to banish darkness, to give it flight.” The congregation responds, “Darkness flees it cannot hide, it leaves this room, it goes outside.”

In another part of the college, a stand-up comedian-cum-devil tells a lewd joke about a bride and groom. The college is populated with the ghosts, ghouls, and student characters from the year book. It is also populated with the various voices and characters of Kelley’s musical history: the stand-up comedian, the vampire, and the ghoul. This time, something has shifted: the improvised music of DAM and The Poetics has become the score, the premeditated act. Popular forms themselves are reheated, brought to life in order to tell a different story. The reductive emotional shorthand of the musical libretto is skewered, made base. What is presented on-screen is always undercut by the lyrics and by the voice.

Your browser does not support the audio element.

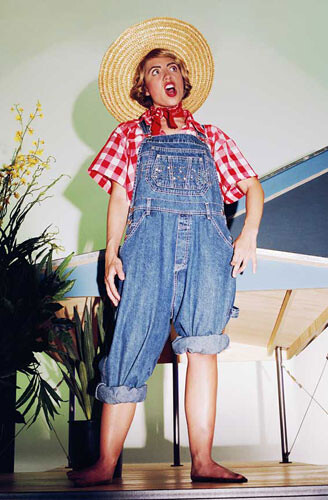

The clearest example of vocal parody-cum-pop mash-up is EAPR#9 (Farm Girl). A young girl in dungarees and gingham stands on stage. Behind her is a scaled-down suburban ranch house. The soundtrack begins with dueling banjos and moves into R&B territory with an ecstatic Mary J. Blige-style undulating vocal, which finishes with the rapidly changing pitch of a yodel: suburban pop meets down-South yodeling hick. The lyrics are comprised of potential titles for Kelley’s work: “Tijuana hayride. Animal sacrifice. Liberal conspiracy. Pick a mascot. Come strong cutie pie. Peaking through the biomorphic wig. At natures mattress. Organic fuck pit. At Rays Burgers. Two balls burgers. For a young buck. Empty surface facility. Used to mask the hurt inside.”

Sex and sexuality, as defined by popular music, looms large. In EAPR#19 (Black Eyed Susan), the somber lilt of English court song delivered by a black-eyed female has become one of barely suppressed sexual yearning: “Lurid purple, velvet turtle. Deep inside my purple cave! Like the muffled cry of a kitten drowning in a well!” The world of hip-hop collides with two far right thugs, hair-slicked back sporting leather jackets and swastikas, who in response to the plump Catholic girl begin to rap: “‘Hidden under a blanket of lard. Two for one that’s what you are! I ride my hog, I don’t mean a bike. A big fat chick is what I like.”

In Phat Goth, a tubby teen-goth stomps to industrial-electronica as she details the ways and means of her occult power. In Hag Mary, the virgin voice is tainted, becoming more like Alice Cooper. Kelley also makes several appearances. In Arbor Day, he appears as the voice of two bushes, a comic book Southern drawl telling the tale of America. In Ol’ Filthy, he is cast in the role of the old man prone to subverting the purity of youth, as he has no other purpose than telling dirty stories. In Morose Ghoul, he haunts the underpass of the Colorado Bridge in Pasadena, searching for “perky flowers,” only to find used condoms.

Your browser does not support the audio element.

Day is Done creates a dialogue with New York and its musical traditions, from Broadway and hip-hop to minimal avant-composition. It is an invocation of the popular that is far from romanticized. Words are valued for their material and physical possibilities as they are turned over and explored in the mouth, passed through the filter of pop traditions. The popular voice is a form of material, something to be stripped down to its component parts and re-articulated, and put to other use.

As with the Goliards, Kelley has taken the popular form of the day, digested it, and rewritten the libretto. Pop has eaten itself, digested its own organs, and in the waste it excretes, Kelley pinpoints its death.

Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence, Divine Liturgy of St. James, 4th Century A.D.

Mike Kelley, Foul Perfection: Essays and Criticism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 101.

“Speculum musicae,” in Music, Words and Voice: A Reader, ed. Martin Clayton Coussemaker (Manchester, UK: Manchester Univ. Press Music, 2008).

13th Century papal decree, Pope John XXII.

Not for Sale: Noise Panel, 2009. Artists Space, organized by Mark Beasley, Performa 09, NYC.

Mike Kelley in conversation with Lee Ranaldo and Mark Beasley, Performa 09: Back to Futurism, (Performa publications: 2010).

“Carly Mike Kelley: An Interview,” Carly Berwick, Art in America, (Nov. 2009)

“To the Throne of Chaos Where The Thin Flutes Pipe Mindlessly.” See →.

Nicole Rudick et al., Return of the Repressed:Destroy All Monsters 1973–1977 (New York: PictureBox, 2011).

“To the Throne of Chaos Where The Thin Flutes Pipe Mindlessly.”

Nicole Rudick et al., Return of the Repressed: Destroy All Monsters 1973-1977, (New York: PictureBox, 2011).

Mike Kelley, Catholic Tastes, Whitney Abrams, 1993.

“To the Throne of Chaos Where The Thin Flutes Pipe Mindlessly.”

Carly Berwick, “Mike Kelley: An Interview by Carly Berwick,” Art in America (Nov. 2009) 170–175.

Mike Kelley, Tony Oursler, Poetics Project, (Watari-UM, 1997).

Mike Kelley, Tony Oursler, Poetics Project, (Watari-UM, 1997) See →.

Wintersole also appears in the performance work Confusion(1982), and a component slide presentation titled An Actor Portrays Boredom and Exhibits His Knick Knack Collection, which shows a sequence of images of the actor with his frog collection assembled on a table.

Memory, Art 21 interview with Mike Kelley, Youtube, PBS, 2005.

EAPR#2 (Party Train), Day is Done: A Film by Mike Kelley, Microcinema, 2009.

The extended version of this text is to appear in a forthcoming publication on The Voice in Performance. The research and subsequent publication is a result of the practice-led Fine Art Ph.D program at Reading University, UK.