The preemptive logic of the “lesser evil” is often invoked to justify the use of a lesser violence to prevent a supposedly greater, projected one. The argument conjures a cold calculus of differentials, one in which good and evil are seen as commodities that are exchanged, transferred, speculated upon and in constant circulation. But, as in our contemporary financial economy, the Leibnitzian theodicy of “the best of all possible worlds” is in crisis, and out of its ruins emerges its twin—the necro-economy of “the least of all possible evils.” Eyal Weizman’s most recent book The Least of All Possible Evils looks specifically at the structure of this argument, the predictive and incalculable conceptions of violence it puts forth, and its redeployment as a means of providing a convenient bogeyman for justifying almost any atrocity committed in the name of even more heinous hypothetical consequences. Looking at the forces shaping international law, at the paradoxes of the humanitarian band-aid, and at the dark art of forensic architecture, EW points to the very shape of a weak negativity that characterizes the withdrawal of any coherent mission for the left.

This article is composed of excerpted passages from The Least of All Possible Evils, chosen and sequenced by the editors to provide another point of reflection on the theme of this issue—a crisis in the conjunction of violence and economy. The excerpts are drawing mainly from the first three chapters—on the historical origins of the lesser evil argument, on its contemporary deployment as humanitarian aid, and on the potential for unlocking violence by employing the inherent elasticity of the law.

***

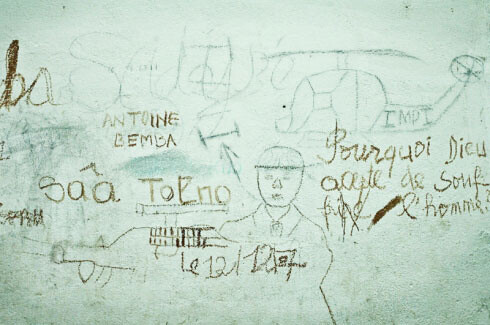

If, as a friend recently suggested, we ought to construct a monument to our present political culture as an homage to the principle of the “lesser evil,” it should be made in the form of the digits 6-6-5 built of concrete blocks, and installed like the Hollywood sign on hillsides or other high points overlooking city centers. This number, one less than the number of the beast—that of the devil and of total evil—might capture the essence of our humanitarian present, obsessed as it is with the calculations and calibrations that seek to moderate, ever so slightly, the evils that it has largely caused.

The principle of the lesser evil is often presented as a dilemma between two or more bad choices in situations where available options are—or seem to be—limited. The choice made justifies harmful actions that would otherwise be unacceptable, since it allegedly averts even greater suffering. Sometimes the principle is presented as the optimal result of a general field of calculations that seeks to compare, measure, and evaluate different bad consequences in relation to necessary acts, and then to minimize those bad consequences. Both aspects of the principle are understood as taking place within a closed system in which those posing the dilemma, the options available for choice, the factors to be calculated, and the very parameters of calculation are unchallenged. Each calculation is undertaken anew, as if the previous accumulation of events has not taken place, and the future implications are out of bounds.

Those who seek to justify necessary evils as “lesser” ones, especially when searching for a rationale to explain recent wars and military expeditions, like to appeal to the work of the fourth-century North African philosopher-theologian St. Augustine. Augustine’s rejection of the principle of Manichaeism—a world strictly divided into good and evil—meant that he no longer saw evil as the perfect mirror image of the good; rather, in platonic terms, he saw evil as a measure of the absence of good. Since evil, unlike good, is not perfect and absolute, it is forever measured and calibrated on a differential scale of greater and lesser. Augustine taught that it is not permissible to practice lesser evils, because to do so violates the Pauline principle “do no evil that good may come.” But—and here lies its appeal—lesser evils might be tolerated when they are deemed necessary and unavoidable, or when perpetrating an evil results in the reduction of the overall amount of evil in the world.

More recently, Pope Benedict XVI has appealed to the lesser evil principle in a decree permitting the use of condoms in places with high rates of HIV. Similar to this logic of contraception, some in the Vatican thought that implicit support for the government of Silvio Berlusconi, albeit plagued by sin, ridicule, and corruption, might be considered as the lesser evil in protecting Christian values. In cases such as these, the economy of the lesser evil is always cited as a justification for breaching rigid rules and entrenched dogma; indeed, it is very often used by those in power as the primary justification for the very notion of “exception.”

In fact, Augustine’s discourse of the lesser evil was developed at a time when the church had started to participate in the political government of its subjects and had acquired considerable financial and military power. Through the ages, the Christian church saw its task as keeping human evil to a minimum. It pastorally ruled over a vast and complex intrapersonal economy of merits and faults—of sin, vice, and virtue—operating according to specific rules of circulation and transfer, with procedures, analyses, calculations, and tactics that allowed the exercise of a specific interplay between conflicting goods and degrees of evil. In his lectures on the origins of governmentality, Michel Foucault argued that, on the basis of this “economical theology,” the modern, secular form of governmental power has itself taken on the form of an economy.1

The theological origins of the lesser evil argument cast a long shadow over the present. In fact, the idiom has become so deeply ingrained, and is invoked in such a staggeringly diverse set of contexts—from individual situational ethics and international relations, to attempts to govern the economics of violence in the context of the “War on Terror” and the efforts of human rights and humanitarian activists to maneuver through the paradoxes of aid—that it seems to have altogether replaced the position previously reserved for the term “good.” Moreover, the very evocation of the “good” seems to invoke everywhere the utopian tragedies of modernity, in which evil seemed to lurk in a horrible Manichaeistic inversion. If no hope is offered in the future, all that remains is to insure ourselves against the risks that it poses, moderate and lessen the collateral effects of necessary acts, and tend to those who have suffered as a result.

In relation to the War on Terror, the terms of the lesser evil were most clearly and prominently articulated by Michael Ignatieff, former human rights scholar and leader of Canada’s Liberal Party. In his book The Lesser Evil, Ignatieff suggested that in “balancing liberty against security,” liberal states should establish mechanisms to regulate the breach of some human rights and legal norms, and allow their security services to engage in forms of extrajuridical violence—which he saw as lesser evils—in order to fend off or minimize potential greater evils, such as terror attacks on civilians in Western states.2

If governments need to violate rights in a terrorist emergency, it should be done, he thought, only as an exception and according to a process of adversarial scrutiny. “Exceptions,” Ignatieff states, “do not destroy the rule but save it, provided that they are temporary, publicly justified, and deployed as a last resort.”3

The lesser evil emerges here as a pragmatic compromise, a “tolerated sin” that functions as the very justification for the notion of exception. State violence in this model is a necro-economy in which various types of destructive measures are weighed in a utilitarian fashion, not only in relation to the damage they produce, but to the harm they purportedly prevent and even in relation to the more brutal measures they help restrain. In this logic, the problem of contemporary state violence resembles an all-too-human version of the previously mentioned mathematical minimum problem of the divine order, one tasked with determining the smallest level of violence necessary to avert the greatest harm. For the architects of contemporary war, this balance is trapped between two poles: keeping violence at a level low enough to limit civilian suffering, yet high enough to bring a decisive end to a given war.4

More recent works by legal scholars and legal advisers to states and militaries sought to extend the inherent elasticity of the system of legal exception proposed by Ignatieff into ways of rewriting the laws of armed conflict themselves.5Lesser evil arguments are now used to defend anything from targeted assassinations and mercy killings, to house demolitions, deportation, and torture,6 to the use of (sometimes) non-lethal chemical weapons, the use of human shields, and even “the intentional targeting of some civilians if it could save more innocent lives than they cost.”7 In a macabre moment, it was even suggested that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki might be tolerated under the principle of the lesser evil. Faced with a humanitarian A-bomb, one might wonder what, in fact, might qualify as a greater evil. Perhaps it is time for the differential accounting of the lesser evil to replace the mechanical bureaucracy of the “banality of evil” as the idiom to describe the most extreme manifestations of violence. Indeed, it is through this use of the lesser evil that self-proclaimed democratic societies can maintain regimes of occupation and neocolonization.

Disproportionality

Military violence endeavors not only to bring death and destruction to its intended targets but also to communicate with its survivors—those that remain, those not killed. The laws of war have become one of the ways in which military violence is interpreted by those who experience it, as well as by global bystanders. It could thus be said to have a pedagogical pretension. It is a violence that should not only convince, but also manufacture the very possibility for conviction.

In contemporary war, the principle of proportionality has become the main translator of the relation between violence, law, and its political meaning. The communicative dimension of military threats can function only if gaps are maintained between the possible destruction that an army is able to inflict and the actual destruction that it does inflict. It is through the constant demonstration of the existence and size of this gap that a military communicates with the people it fights against and occupies. Sometimes the gap opens wide, such as when the military governs the territories it occupies—its violence in a state of potential, existing as a set of threats and possibilities that are not, for the time being, actualized. In a state of war, the gap closes—but rarely does it do so completely. Even in the most brutal wars, something of the gap still exists as the stronger side restrains and moderates its full destructive capacity. Restraint is also what allows for the possibility of further escalation, an invitation for the victims violence to make their own cost-benefit calculation and opt for consent. A degree of restraint is thus part of the logic of almost every military operation: however bad military attacks may appear to be, they can always get worse. This is measured against “the potentiality of the worst”—an outburst of performative violence without rules, limits, proportion, or measures—which has to be demonstrated from time to time.

The gap thus communicates the potential for destruction without the need for further violence. When the gap between the possible and the actual application of force closes completely, violence loses its function as a language. War becomes total war—a form of violence stripped of semiotics, in which the enemy is expelled, killed, or completely reconstructed as a subject. Degrees in the level of violence are precisely what makes war less than total. Game theory, as applied by military think tanks since the early Cold War days of RAND, is conceived to simulate the enemy’s responses, and help manage the gap between actual and potential violence. This practical form of military restraint is now often presented as adherence to the laws of war.

Disproportionality—the breaking of the elastic economy that balances goods and evils—is violence in excess of the law, and one that is directed at the law. Disproportional violence is also the violence of the weak, the governed, those who cannot calculate, and those who are outside of the economy of calculations. This violence is disproportional because it cannot be measured and because, ultimately, having its justice not reflected in existing law, it comes to restructure the basis of existing law altogether.

The calculations of proportionality as a technique of management and government—the management of violence and the government of populations—is undertaken by the powerful side “on behalf” of those it subjugates. Moreover this power is in fact grounded in the very ability to calculate, count, measure, balance and act on these calculations. Inversely, to make oneself ungovernable, one must make oneself incalculable, immeasurable, and uncountable.

Minima Moralia

“During the Bosnia war I was at a crossroads. On the one hand I continued to pursue positions inherited from the Cold War; on the other, I was trying to get my bearings in the new world we were suddenly living in after the Berlin wall came down”—so said Rony Brauman, president of Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières, or MSF), to the philosopher and publisher Michel Feher in a famous interview. Brauman went on to note that at the beginning of the wars of the former Yugoslavia, “we were very explicitly influenced by Hannah Arendt, [as] Bosnia seemed like the traditional confrontation between liberal democracy and totalitarianism … and I responded in the liberal way, by raising the flag of human rights.”8 But as raising the flag of human rights meant military intervention, this position also clashed with Brauman’s aversion to a humanitarianism that could be absorbed into state politics and military strategy.9 Moreover, he thought making public MSF’s opinion on juridical categories such as “‘crimes against humanity’—which has always had an implicit reference to the Nazi camps—has political, military, and legal consequences beyond our control. The language one uses both frames the problem and determines the kind of response. To say ‘crimes against humanity’ is to call for immediate military intervention to stop it—and this is beyond the mandate of humanitarianism.”10

In the face of this bold humanitarian vision, with its violent cosmopolitan order of geopolitical statements and calls for humanitarian intervention, Brauman started to promote humanitarianism in its minimalist form: humanitarianism as the practice of lesser evils. The lesser evil, in the way that Brauman refers to it, is a humanitarianism that sustains life without seeking to govern or manage populations, without making political claims on their behalf or seeking to resolve root causes of conflicts. It is a humanitarianism that unashamedly and impartially deals with the problems of “bare life.” This concept, designating the vulnerability of a life stripped of any civil and political rights that might protect it, comes from the philosopher Giorgio Agamben. In recent years, “bare life” has been popularized in the context of the critique of humanitarian action.11 In what might be defined as the critique of the critique of humanitarianism, Brauman made sure to adopt the very terms in which he was criticized: “Of course, we take care of the bodies. We as aid workers try to maintain life … I would, on the contrary, feel very uncomfortable if we were trying to do more—to control or penetrate people’s minds. What people ask us, what they expect from us, is to help them survive. For the rest, they can manage by themselves.”12 “Upholding a vision of humanitarianism as the policy of the lesser evil,” in Brauman’s view, is a temporary autonomous act of solicitude that “is about little more than the caring for bodies.” Politics based in medicine, he states, must be abandoned in exchange for the obvious: the actual practice of humanitarianism and clinical medicine. It is in this sense that “accepting the policy of the lesser evil … becomes one of the ways to live with the contradiction [of humanitarianism] without completely becoming a victim of it.”13

But this is a different conception of the “lesser evil” argument than the one Brauman rejected in his withdrawal from Ethiopia, where it concerned collaboration with “totalitarians.” It is also different than that articulated by the likes of (Bernard) Kouchner and (Bernard-Henri) Lévy, who conceive the idea from the point of view of the state and Western values, in the context of fighting in the name of the “lesser evil” of democracy. It is also different from the “ethical realism” of Michael Ignatieff, in which the practice of the lesser evil demands the imposition of ethical constraints on states’ actions while in the pursuit and defense of “moral goals” such as freedom, human rights, and democracy.14

Against what Brauman calls the “imperial policy of humanitarianism,” his meaning of the lesser evil designates the project of humanitarianism at its most minimal—as one that “takes no political stand, makes no claim to transform society, and doesn’t come to make war or peace, promote economic development, help administer justice, or export democracy or human rights values.”15 These, he thinks, are not necessarily bad things in themselves, but they are the responsibility of the politicians and have little to do with humanitarianism as such, which in its minimal, independent, impartial, and barest meaning should seek to provide nothing more than immediate, short-term relief and medical aid—what David Rieff, following Bertolt Brecht, called “a bed for the night.” Such humanitarianism “won’t change the world”—nor does it seek to.16

This minimal approach to humanitarianism has found its spatial manifestation in what Brauman called a “humanitarian space.” In his conception, the humanitarian space is a form of spatial practice rather than an actual space or a territorial designation. Against the tendency of conflicts since the 1980s to generate integrated and entangled political-military-humanitarian spaces, mainly around refugee camps, this space is conceived in order to hold relief work at a distance from political and military practice.

Driving the humanitarian present is no longer a sense of naive yet dangerous compassion, but rather a highly specialized and concerted international effort to manage populations that are seen as posing risks. In his work on the refugee camps of Africa, the anthropologist Michel Agier refers to contemporary humanitarianism as nothing less than “a distant and delegated form of management, a government without citizens.”17 He describes the humanitarian zones as heavily guarded and tightly policed “waiting rooms on the margins of the world,” built and maintained for the purpose of the “total government of the planet’s populations who are most unwanted and undesirable.” In them, the well-meaning humanitarians “find themselves acting as low-cost managers of exclusion on a planetary scale.”18 Refugee camps are part of an overall system of migration control, he says, intended to provide for displaced populations at a discreet distance from Western shores. They are an island in an archipelago of extraterritoriality, which also includes extended border control practices and detention centers. Humanitarianism’s earlier obsession with identifying and sorting out perpetrators from victims is here rendered irrelevant as both categories morph into that of the potential migrant, whose entry into Western countries must be stopped at any price. Displaced populations become the concern of the international community precisely because of the risks they pose. The fear of migration, crime, and terrorism is conceived of as being in inverse relation to the well-being of populations. This tendency is best captured by the term “human security,” under which every dimension of human life—from food and shelter to education—is measured within a shifting calculus of risk.

Humanitarianism should indeed aim to provide no more than the bare minimum to support the revival of life after violence and destruction. As long as refugees are alive, the potential for political transformation still exists. The very life of refugees, poses a potent political claim with transformative potential, one that represents a fundamental challenge to the states and state system that keep them displaced. This is the reason that generations of political leaders, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo through to Kosovo and Palestine, emerge from among the refugees to become the vanguard of political struggles. The refugees’ return to politics has unpredictable consequences, which are and must always remain beyond the horizons of humanitarians and aid groups. Only when humanitarianism seeks to offer temporary assistance rather than to govern or develop can the politics of humanitarianism really create a space for the politics of refugees themselves. This shift demands that we think about the politics of aid not only from the perspective of the paradoxes and dilemmas of the relief workers and the people that send them, not only concerning the problems of humanitarian cooption, evasion, government and refusal, but primarily from the question of the politics of refugees, their claims, their rights and their potential actions, their wishes, their exercise and their evasion of power, their potential return. It might be that only with the ultimate refusal of aid at a time of their choice—with the rejection of the very apparatus that sometimes keeps them in good health, and sometimes operates to manage their exclusion—with refugees constructing their own spaces, self-governing, posing demands and acting upon them—that the potentiality of their political life will actualize. Then, where there were camps there could be cities.

Lawfare

If, therefore, conclusions can be drawn from military violence, as being primordial and paradigmatic of all violence used for natural ends, there is inherent in all such violence a lawmaking character.19

—Walter Benjamin

Israel’s bombing and invasion of Gaza in the winter of 2008–9 marked the culmination of its violence against the Palestinians since the Nakba of 1948, and resulted in widespread international allegations that Israel had committed war crimes. It was also the assault in which Israeli experts in international humanitarian law—the area of the law that regulates the conduct of war—were more involved than ever before. Since the 2006 Lebanon War, the Israeli military has become increasingly mindful of its exposure to international legal action. Preparations for the next conflict included those in the domain of law, and new “legal technologies” were introduced into military matters.

This development gives rise to a series of related questions. Might it be that these legal technologies contributed not to the containment of violence but to its proliferation? That the involvement of military lawyers did not in fact restrain the attack—but rather, that certain interpretations of international humanitarian law have enabled the inflicting of unprecedented levels of destruction? In other words, has the making of this chaos, death, and destruction been facilitated by the terrible force of the law?

In more domains than one, the elastic and porous border has become the contemporary pathology of Israel’s regime of control. It manifests itself in a variety of ways—one such being the elasticity that military lawyers identify and mobilize in interpreting the laws of war.

As such, the laws of war pose a paradox to those protesting in their name: while they prohibit some things, they authorize others. And thus a line is drawn between the “allowed” and the “forbidden.” This line is not stable and static; rather, it is dynamic and elastic and its path is ever changing. An intense battle is conducted over its route. The thresholds of the law will be pulled and pushed in different directions by those with different objectives. The question hinges on which side of the legal/illegal divide a certain form of military practice falls. International organizations such as the UN and the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross), large NGOs and human rights groups, and also some highly regarded academic authorities on international humanitarian law have the means to push the line in one direction—to place controversial military practices on the prohibited side—while state militaries and their apologists seek to push it in the opposite direction. International law can thus not be thought of as a static body of rules but rather an arena in which the law is shaped by an endless series of diffused border conflicts.

According to Eitan Diamond, the legal scholar and adviser for the ICRC in Israel, “the architecture of international humanitarian law is typified by ‘rigid lines of absolute prohibition’ and ‘elastic zones of discretion.’” The rigid prohibitions are derived, he states, from the law’s origins in the nineteenth century, “a time when legal thought was dominated by a positivist-formalist approach that conceived of law as a closed system distinguished from politics and ethics.” Today, he fears, “states and their advocates are using arguments based on the logic of the ‘lesser evil’ to subvert the law’s absolute provisions and to subject them to malleable cost-benefit calculations.”20

Indeed, new frontiers of military practice are being explored via a combination of legal technologies and complex institutional practices that are now often referred to as “lawfare”—the use of law as a weapon of war. Lawfare is a compounded practice: with the introduction and popularization of international law in contemporary battlefields, all parties to a conflict might seek to use it for their tactical and strategic advantage. The former American colonel and military judge Charles Dunlap, who was credited with the introduction of this term in 2001, suggested that “lawfare” can be defined as “the strategy of using—or misusing—law as a substitute for traditional military means to achieve an operational objective.”21 In the hands of non-state actors, Dunlap says, the “lawfare effect” is created by an interaction between guerrilla groups that “lure militaries to conduct atrocities” and human rights groups that engage in advocacy to expose these atrocities, and who use whatever available means for litigation they have. In a similar vein, Israel now often claims that it faces an unprecedented campaign of lawfare, which threatens to undermine the very legitimacy of the state. Lawfare is used tactically by state militaries themselves. In this context, it refers to the multiple ways by which contemporary warfare is conditioned, rather than simply justified, by international law.22 In both cases, international law and the systems of courts and tribunals that exercise and enact it are not conceived as spaces outside the conflict, but rather as battlegrounds internal to it.

It is within the “elastic zones of discretion” that Israeli military lawyers find enormous potential for the expansion of military action. Daniel Reisner, a former chief international lawyer for the Israeli military, argued that because international humanitarian law is not so much a code-based legal system but a precedent-based legal corpus, state practice can continuously shift it.

International law is a customary law that develops through a historic process. If states are involved in a certain type of military activity against other states, militias, and the like, and if all of them act quite similarly to each other, then there is a chance that this behavior will become customary international law.23

It is in this sense that international law develops through its violation. In modern war, violence legislates: “If the same process occurred in criminal law, the legal speed limit would be 115 kilometres an hour and income tax would be 4 per cent.”24

Reisner is proud to have been the first international lawyer to have defended, at the request of then-Prime Minister Ehud Barak, the policy of “targeted assassinations” towards the end of 2000, when most governments and international bodies considered the practice illegal. “We invented the targeted assassination thesis and we had to push it. At first there were protrusions that made it hard to insert easily into the legal molds. Eight years [and, as he subsequently said in this interview—by way of reference to 9/11—‘four planes’] later it is in the center of the bounds of legitimacy.”25

Asa Kasher, a professor of ethics at Tel Aviv University, has worked with Reisner to provide an ethical and legal defense for targeted assassination. He talks in similar terms about the nature of law and the ways in which it might be transformed:

We in Israel have a crucial part to play in the developing of this area of the law [international humanitarian law] because we are at the forefront of the war against terror, and [the tactics we use] are gradually becoming acceptable in Israeli and in international courts of law … The more often Western states apply principles that originated in Israel to their own non-traditional conflicts in places like Afghanistan and Iraq, then the greater the chance these principles have of becoming a valuable part of international law. What we do becomes the law.26

The actions of the Israeli state against Gaza may become acceptable in law. The siege—ongoing since 2007—the 2008–9 invasion, and the 2009 attack on an international flotilla carrying supplies into the enclave have all been carried out with relative impunity, and do not appear to have significantly affected Israel’s international standing. Each of these forms of aggression contains within it a multiplicity of small-scale practices and incidents: restricting the supply of food to the point of starvation; targeted assassinations; sending advance warnings that then allow the military to kill those civilians who choose not to evacuate;27 attacks on activists in international waters; the use of white phosphorus in inhabited areas—the list goes on. In these acts—if Israeli lawyers have their way—lie the seeds of new legislation.

Working at the margins of the law is one way to expand them. For violence to have the power to legislate, it needs to be applied in the grey, indeterminate zone between obvious violation and possible legality, and then to be defended diplomatically and by legal opinion. Indeed, the legal tactics sanctioned by military lawyers in Israel’s invasion of Gaza in 2008–9 were framed in precisely this way. “When something’s in the white zone, I’ll let it be done, if it’s in the black I’ll forbid it, but if it’s in the grey zone then I’ll take part in the dilemma, I don’t stop at grey,” said Reisner.

The invasion therefore did two simultaneous and seemingly paradoxical things: it both violated the law and shifted its thresholds. This kind of violence not only transgresses but also attacks the very idea of rigid limits. In this circular logic, the illegal turns legal through continuous violation. There is indeed a “law-making character” inherent in military violence. This is law in action, legislative violence as seen from the perspective of those who write it in practice.

This use of the law has much in common with that of the George W. Bush Administration’s misappropriation of the Office of Special Counsel in the Justice Department, in order to figure out a way to legalize the use of torture. Inherent in this was the clear intention to stretch the law as far as possible without actually breaking it.28 In this example, US Department of Justice attorney John Yoo used the balancing of interests to authorize certain forms of torture. His famous torture memos were grounded in an Israeli precedent: relying on what is essentially a proportionality analysis, the 1987 Israeli commission of inquiry into the methods of investigation in the General Security Service (the Landau Commission) arrived at the conclusion that the prohibition on torture is not absolute, but is rather based “upon the logic of the lesser evil.”

Thus, “the harm done by violating a provision of the law during an interrogation must be weighed against the harm to the life or person of others which could occur sooner or later.”29 Some legal scholars have suggested that Yoo’s legal advice in itself might be considered a crime.

Similar lines of legal argument are inspired by a strand of legal scholarship known as “critical legal studies,” an approach that emerged together with other post-structuralist discourses at the end of the 1980s. Critical legal studies scholars aimed to expose the way the law is made—the workings of power in the making and enactment of law—to challenge law’s normative account and to offer an insight into its internal contradictions and indeterminacies. It was, broadly speaking, a critical, left-leaning practice, which attempted to deploy law at the service of a socially transformative agenda. But when international law stands as an obstacle in the way of state militaries, it is easy to see why military lawyers would adopt the attitude of those scholars seeking to challenge rigid definitions and expose the law as an object of critique and contestation. Today, when the creative interpretation of the law is exercised by state and military lawyers, it is primarily human rights and antiwar activists who insist on the dry letter of the law. Have we gone full circle?

In the age of lawfare, the elastic nature of the law, and the power of military action to stretch it, those appealing for justice in the name of the law need to be aware of its double edge.

Gaza is a laboratory in more than one sense. It is a hermetically sealed zone, with all access controlled by Israel (except the border with Egypt). Within this enclosed space, all sorts of new control technologies, munitions, legal and humanitarian tools, and warfare techniques are tried out on its million-and-a-half inhabitants. The ability to remotely control large populations is also tested, before these technologies are marketed internationally. Most significantly of all, it is the thresholds that are tested and pushed: the limits of the law, and the limits of violence that can be inflicted by a state and be internationally tolerated. This limit, newly defined with every attack, will become the new threshold of what can be done to people in the name of the War on Terror. When the legislative violence directed at Gaza unlocks the chaotic powers of destruction that lie dormant within the law, the consequence will be felt by oppressed people everywhere.

Epilogue

Is there, then, a horizon from which we can see beyond the logic of the lesser evil? The epilogue of the book provides one such example.

The predominant conceptual frame by which refugee camps are understood is one in which every physical improvement at present is a potential threat to the provisional nature of the camp. Urbanizing the camp, making it permanent, might sacrifice the “right of return” to which its temporariness otherwise testifies. But a new generation of scholars and architects—prominent among them are Ismael Sheikh Hassan and Sari Hanafi in Lebanon, and Alessandro Petti, Nasser Abourahme and Sandi Hillal in Palestine—have attempted to challenge the conceptualization of refugee habitats as mere repositories of national memory.30 The stronger the camp, they argue, the better the chances of it becoming a political space, a platform on which refugees’ political claims could be articulated and the struggle continued. In Nahr el-Bared in Lebanon, after its destruction by the Lebanese army in 2007, and in the camps of Gaza and those of the West Bank that shouldered much of the burden of ongoing resistance, they worked with refugee communities and UN agencies to pick up the rubble, to design and promote programs for camp improvement and experimented with new pedagogical platforms in it.31

For those that remained in the camp, and for those that live just outside it, they sought to reinforce the camp as a vibrant living space with community services and political institutions. An improved camp with open access, public spaces, new forms of educational institutions, updated physical and communication infrastructure and better homes is not a negation of the right of return but rather a tool for its reinforcement. Such a camp could provide a platform for political mobilization. This point of view rejects both the accommodation to an unjust political reality and the politique du pire that seeks to maintain misery and invest it with political meaning. The reconstruction of Gaza, when and if it is made possible, might mean the arrival of some international organizations and state donors with a multiplicity of agendas and the means to pursue them. Facing this well-meaning aid, refugees will have to adopt a delicate process of navigating between poles. Homes must be rebuilt, infrastructure laid out, camps and life improved, not instead of but rather in order to support political rights and the continuous struggle to achieve them. This will still be much less than perfect, but it is certainly not the choice of the lesser evil.

Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College de France 1977–1978, ed. Arnold I. Davidson, trans. Graham Burchell, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 164–73, 183.

Michael Ignatieff, The Lesser Evil: Political Ethics in an Age of Terror, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

Ibid., xiv.

These refer respectively to jus in bello and jus ad bellum.

A former Israeli military lawyer Gabriella Blum opines that if international humanitarian law “is designed to minimize humanitarian suffering within the constraints of war, then it is not at all clear why measures intended to further minimize suffering … a choice for the lesser evil – cannot serve as a justification,” she says effortlessly, “for suspending the law in the name of the law.” Gabriella Blum, “The Laws of War and the ‛Lesser Evil,’” (35 YJIL 1, 2010), 3.

Relying on what is essentially a proportionality analysis, the Israeli Commission of Inquiry into the Methods of Investigation of the General Security Service Regarding Hostile Terrorist Activity, otherwise known as the Landau Commission, of 1987 reaches the conclusion that the prohibition on torture is not absolute, but is rather based, in its own words, upon the logic of “the lesser evil.” Thus, “the harm done by violating a provision of the law during an interrogation must be weighed against the harm to the life or person of others which could occur sooner or LATER” (upper-case in the original). US Department of Justice attorney John Yoo similarly referred to a balance of interests when authorizing forms of torture during the Bush Administration. Itamar Mann and Omer Shatz, “The Necessity Procedure: Laws of Torture in Israel and Beyond, 1987–2009,” Legalleft, 2011, see →.

Ibid., 3.

Brauman, “Learning from Dilemmas,” 136.

During the other prominent crises of the 1990s his pronouncements and actions called for humanitarianism to be positioned away from militaries—Western or otherwise. During the war in Somalia it was about the militarization of the “humanitarian mission that ended up shooting many of the people it came to protect. Several months after the massacres in Rwanda it was about the way that the Hutu militias that undertook them were using international aid in order to regroup and use the refugee camps as rear bases for guerilla action. He equally protested the way in which Rwandan and Burundian forces used humanitarian aid as bait to capture other Hutu refugees in Zaire.

Brauman in interview, September 2010.

See especially Michel Agier, On the Margins of the World: The Refugee Experience Today, trans. David Fernbach, (London: Polity, 2008).

Eyal Weizman and Rony Brauman in conversation, Columbia University, 4 February 2008.

Brauman, “Learning from Dilemmas,” 141.

Michael Ignatieff, The Lesser Evil: Political Ethics in an Age of Terror, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

Brauman in interview, September 2010.

David Rieff, A Bed for the Night: Humanitarianism in Crisis, (London: Vintage, 2002).

Michel Agier, “The Undesirables of the World and How Universality Changed Camp,” 16. May 2011, →.

Agier, On the Margins of the World, 60.

Walter Benjamin, “Critique of Violence,” trans. Edmund Jephcott, in Peter Demetz, ed., Reflections (1978), 283.

Eitan Diamond, “Reshaping International Humanitarian Law to Suit the Ends of Power” at the conference Humanitarianism and International Humanitarian Law: Reflecting on Change over Time in Theory, Law, and Practice, held at the Law School, the College of Management Academic Studies in Rishon Lezion, 16–17 December 2009.

Charles J. Dunlap, “Lawfare: A Decisive Element of 21st-Century Conflicts?,”Joint Force Quarterly 3, (2009), 35. See also Charles J. Dunlap, “Law and Military Interventions: Preserving Humanitarian Values in 21st-Century Conflicts,” at Humanitarian Challenges in Military Intervention (Conference), Carr Center for Human Rights Policy in the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 29 November 2001. See also Charles Dunlap, “Lawfare amid Warfare,”Washington Times, 3 August 2007.

David Kennedy, Of War and Law, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 33.

Asa Kasher, “A Moral Evaluation of the Gaza War,” Jerusalem Post, 7 February 2010.

See Yotam Feldman and Uri Blau, “Consent and Advise,” Ha’aretz, 5 February 2009.

Ibid.

Asa Kasher, “Operation Cast Lead and the Ethics of Just War,” Azure, no. 37, (summer, 2009): 43–75.

The military’s “international law division” and its operational branch have devised tactics that would allow soldiers to apply what might be called “technologies of warning.” Delivered to homesteads by telephone or sometimes by warning shots, they aim to shift people between legal designations—as soon as a civilian picks up the phone in his home, his legal designation changes from an “uninvolved civilian,” protected by IHL, to a voluntary “human shield”—from a subject to an object, a simple part of the architecture. Technologies of warning intervene in the legal categories of both “distinction” and “proportionality”: with regard to the former, they transfer people from illegitimate to legitimate targets by forcing them into a legal category that is not protected; and with regard to the latter, they imply a different calculation of proportionality. Human shields are not designated as combatants but are not counted as uninvolved civilians in the calculations of proportionality which must assess damage against the life lost.

John Yoo, The Powers of War and Peace, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

Itamar Mann and Omer Shatz, “The Necessity Procedure: Laws of Torture in Israel and Beyond, 1987–2009,” Legalleft, 2011, see →.

Some of these crimes were in fact investigated and prosecuted by the Israeli military’s courts. Human Rights Watch, “Witness Accounts and Additional Analysis of IDF Use of White Phosphorus,” online, 25 March 2009. See →.

In the nineteenth century, photographs as courtroom evidence were often understood as pale substitutes for evidence, posing legal challenges and even being referred to as “the hearsay of the sun.” Photographic images were banned from courts. But once entered, they still were treated with much suspicion and ultimately had to prove their status as reliable evidence. See: Joel Snyder, “Res Ipsa Loquitur,” Lorraine Daston, ed.,Things That Talk: Object Lessons from Art and Science, (New York: Zone Books, 2007).