In 1963 NASA launched the first communications satellite, Syncom 2, into a geosynchronous orbit over the Atlantic Ocean. Since then, humans have slowly and methodically added to this space-based communications infrastructure. Currently, more than 800 spacecraft in geosynchronous orbit form a man-made ring of satellites around Earth at an altitude of 36,000 kilometers. Most of these spacecraft powered down long ago, yet continue to float aimlessly around the planet. Geostationary satellites are so far from earth that their orbits never decay. The dead spacecraft in orbit have become a permanent fixture around Earth, not unlike the rings of Saturn. They will be the longest-lasting artifacts of human civilization, quietly floating through space long after every trace of humanity has disappeared from the planet’s surface.

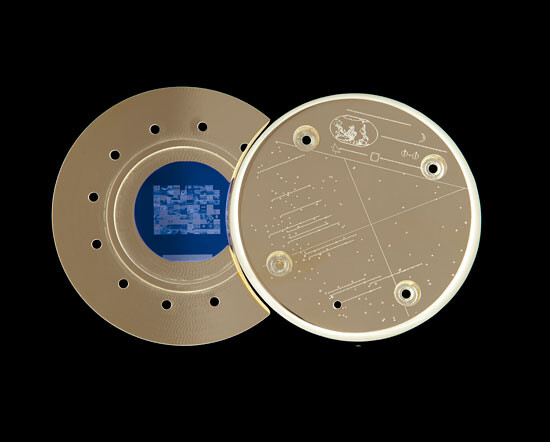

Commissioned and presented by public art organization Creative Time, The Last Pictures is a project to mark one of these spacecraft with a record of our historical moment. For nearly five years, artist Trevor Paglen interviewed scientists, artists, anthropologists, and philosophers to consider what such a cultural mark should be. As an artist-in-residence at MIT, he worked with materials scientists to develop an archival disc of images capable of lasting in space for billions of years.

In September 2012, the television satellite EchoStar XVI will lift off from Kazakhstan with the disc attached to its anti-earth deck, enter a geostationary orbit, and proceed to broadcast over ten trillion images over its fifteen-year lifetime. When it nears the end of its useful life, EchoStar XVI will use the last of its fuel to enter a slightly higher “graveyard orbit,” where it will power down and die. While EchoStar XVI’s broadcast images are destined to be as fleeting as the light-speed radio waves they travel on, The Last Pictures will continue to slowly circle Earth until the Earth itself is no more.

***

Nato Thompson: It is great that we have an opportunity to talk about The Last Pictures after working on it for numerous years. There is a lot to tackle in this project, in that it is this sort of grand gesture (going to space) with a critique of that very gesture.

Trevor Paglen: This has been a very strange project to work on, as you can imagine. The notional framework is to create a collection of images for the far future, a future where there is no evidence of human civilization on Earth’s surface, but where a ring of dead spacecraft remains in orbit, perhaps for the descendants of future dinosaurs or giant squid to find. So right from the start, we have a situation that is utterly absurd. The idea that we can “communicate” anything whatsoever to anything outside our own social and historical context is preposterous. But that doesn’t change the material fact that our communications satellites will, in all likelihood, really be in orbit around Earth for the next four or five billion years (until the Sun expands into a red giant), and The Last Pictures may very well be the “last pictures.” How, as an artist, does one navigate between these two poles? It’s an impossible task and an impossible question. Over the course of researching this project, several touchstones became really important to me. The most important is cave paintings, and in particular a tableau from Lascaux called “the Pit” or “the Shaft.” Cave paintings are an example of images or records we have from cultures that have been radically torn from any historical context. They are to us what our spacecraft may be to the future. I actually think about The Last Pictures as cave paintings for the future.

NT: One of the obvious jumping-off points was Carl Sagan’s Golden Record of 1974, which was a tremendous encyclopedic attempt to communicate with aliens.

TP: Yes. Another touchstone for the project is the history of objects or messages that are specifically designed for extraterrestrials, objects that are designed as gifts for an alien in the far future—and over the course of this project, the figure of the alien and the “figure” of the future have become completely intertwined in my own thinking. Of these objects-for-aliens, the Golden Record is the most elaborate. At first glance, the Golden Record seems very much like an artifact of the 1970s. It’s an LP record attached to the Voyager space probe. One side holds a collection of world music and greetings in fifty-five different languages, and the other side has a collection of images encoded into a video signal. The images are a cross between The Family of Man and National Geographic, which is actually the source for most of them. When you look at the Golden Record’s contents, it looks a lot like a kind of “it’s a small world” multicultural utopia. No images of war, poverty, inequality, environmental destruction. You can imagine the obvious critiques. The more I look at these images, the more bizarre it is and the more sympathetic I’ve become towards it. On one hand, working on The Last Pictures has actually taught me a lot about images, mostly about how overflowing with excess images are, how utterly alien they become when they float away from their immediate contexts. Cave paintings, or even things like pyramids or the Moai of Easter Island, are deeply strange artifacts to us—so strange, in fact, that some of the most popular shows on TV are about trying to “uncover their mysteries,” and so forth. All images are ultimately cave paintings. A fun exercise to demonstrate this: take out all the pieces of music and languages that are familiar to you, then play the unfamiliar ones over a slideshow of the images. The “it’s a small world” read goes away quite quickly.

NT: It’s a strange time we live in, as I can’t help but notice a certain “nihilism,” as you put it, in terms of a general mood of gloom with respect to the future. At first, you were rather cynical about this project, in that you felt it was completely absurd and perhaps even demonstrated the hubris of the modern project. I believe you said it has something to do with the ethics of time.

TP: When I began The Last Pictures, I thought that the idea of creating human marks on timeless spacecraft was an absurd idea. But over the years, I started to think that not marking our spacecraft, and not marking things for the future may be symptomatic of a culture in which we actively annihilate the future through our disregard for it. Environmental destruction is an obvious example of this attitude, as is cutting education budgets. And so, in this way, the idea of creating “greetings” for the alien/future seems to embody an ethics in which we imagine that the future actually exists and, perhaps, as a consequence, care more about it. I don’t want to come off as a big advocate for the Golden Record or say how great it is, but I think when we look at it and say “it’s naïve,” or “it’s so 1970s,” it’s a fine line between pointing out (rightly) problems with the meta-gesture of the Golden Record and a nihilistic attitude towards the future that’s widespread right now in culture, society, and politics.

NT: I can’t help but think global warming has radically altered the global ontology. Thinking about the future seems to be almost a luxury. How does all this fit into The Last Pictures?

TP: When we look at a problem like global warming, it appears very clear that our contemporary political and social institutions aren’t up to the task of dealing with challenges that happen at the scale of the planet and that play themselves out on timescales that intersect human time but aren’t exactly aligned with it. In The Last Pictures book, I argue that the last 150 years or so were characterized by increasingly acute temporal contradictions. On one hand, the logics of capitalism and warfare have fueled a constant speeding up and mastery of time—whether it’s the time of post-industrial production, the just-in-time supply lines, factory automation, flexible labor, and so forth with regard to capitalism, or the militarization of space-time through drones, cybernetic warfare, GPS, and so forth. But, curiously, this domination of time has happened at the other end as well, so to speak. At the same time that humans developed machines to communicate at the speed of light, they developed machines capable of industrializing the “time” of the atmosphere, evolution, and even the deep-time of geomorphology. Some geologists point out that over the last hundred years or so, things like real estate markets have become geomorphic agents—fluctuations in commercial real estate markets can move more sediment than “natural” geomorphic processes like erosion or tectonics. Something like global warming is a perfect example of what I think of as a contradiction in time—global warming is an earth process that will play out over the next century or so, but it largely emerges from the industries controlled by business turnover times of a few months (at most). On top of that, we live in a political system where the turnover time of politics is a few years at a time (between elections, for example) and there’s little incentive to address problems whose effects play out on a longer temporal scale than an election cycle. I think that global warming in a great example of how these contradictory time scales produce effects that humans have few credible means of dealing with. These material contradictions are the “stuff” that The Last Pictures is made out of—it’s a communications satellite delivering signals at the speed of light, put in the service of quarterly profits for the company that owns it, amortized over its fifteen year lifespan, that will become a ghost ship that lasts in orbit forever. It’s all there. I don’t mean to be all doom-and-gloom, especially when we also see such amazing things as the Egyptian revolution and of course mass mobilizations like Occupy. At the same time, the post-’89 world we find ourselves in seems to definitively vindicate Benjamin over Marx: revolutions aren’t Marx’s “locomotives of history” so much as what Benjamin called the “human race grabbing for the emergency break.” It is no coincidence that the first image in The Last Pictures is a photograph of the back of Klee’s Angelus Novus.

NT: I get the feeling that it isn’t just that you are playing with time, but instead that the deep time of this project itself, billions of years, forces an almost exponential consideration of the implications of what it means to communicate across vast gaps in time.

TP: The old nineteenth-century idea of Progress seems to be pretty definitively over these days, which I think is partly what you mean when you say that thinking about the future seems like a luxury. That’s one of the things I like about The Last Pictures being in geostationary orbit—instead of the “linear” time of spacecraft that boldly explore the unknown, like the USS Enterprise or the Voyager probe, the perpetual circling of The Last Pictures is more like Blanqui’s eternal recurrence—and his own critique of progress. I’ve definitely come to the point where I don’t think about the Last Pictures as having very much to do with communication at all. I don’t think that anyone will ever find our artifact, and even if the dinosaurs came back in 100 million years and developed spaceflight and found our object, the images wouldn’t mean anything at all. It seems to me that the notion of “meaning” might itself be a relatively contemporary idea. So what is the status of The Last Pictures? The closest thing we have to an analogy as to what these images might “mean” for the future is what cave paintings “mean” to us. Of course, we have absolutely no idea what cave paintings “mean,” and I strongly suspect that our notion of meaning here is part of the problem.

NT: You have said to me that you loved reading Bataille’s take on the Lascaux cave paintings but that you felt he didn’t go far enough. Why didn’t Bataille go far enough? What do cave paintings say to you?

TP: Yates McKee got me thinking about cave paintings pretty early in the research process. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about a particular image from Lascaux, the famous painting in “the Pit” or “the Shaft,” which is one of the one hundred images I included in The Last Pictures. Pre-historians have offered all sorts of theories about this bizarre image, from it being a depiction of a hunt gone wrong to some sort of shamanistic tableaux. In the book, I recount some of these theories about the image, and then conduct a thought experiment: I assume that the artist who made that painting is just as sophisticated as any contemporary artist in terms of understanding what he or she was doing as an image-maker. My frustration with a lot of the pre-historians is that they see the painting as the work of “Primitive Man,” rather than as the work of a reasonably sophisticated artist who happened to live tens of thousands of years ago. Bataille is much more generous to the prehistoric artist and is able to think through the “meaning” of various images from Lascaux in a more creative way than his contemporaries, but I think he’s still stuck on the idea of reading the paintings through his own notion of the “primitive” and his own notion of some kind of unified “early Man” whose collective unconscious is somehow expressed in the paintings. I think we should get rid of the idea of “primitive” and drop the idea that a cave painting is some kind of Jungian collective-unconsciousness image. If we do away with those two premises, then our reading of the paintings can get pretty unorthodox pretty quickly.

NT: So then we have two radically different periods of time that this project is considering; the extremely distant future billions of years from now and one that is this very slight, very tenuous thing we know as the immediate present. If you truly feel that no one will actually find this artifact, why go through all the trouble of getting it in space? Why make something that will only make sense now and claim it is meant for the distant future?

TP: That’s one of the many paradoxes at the core of this project. I don’t think that it will ever be “found,” nor do I think that it would look like anything more than a handful of nonsensical scratchings if anyone ever did find it. But I could be wrong, and much of the project has been an enormous effort organized around the idea that I might be wrong. On one hand, the project is destined to be non-sense, because it is going to a place and time where “sense” does not exist. Incidentally, I disagree that the project “makes sense now”—it makes no sense to me at all; it is a frozen contradiction. On the other hand, the title is not a metaphor—this collection of images really might be the “last.” And it seems to me that that fact—regardless of whether it’s nonsensical—comes with an enormous amount of responsibility. I spent years thinking through the ethics of this project, interviewing the smartest people I could find and conducting weekly seminars and directed research with a great group of students to think through the ethical maze of this project. Regardless of whether anyone will ever find the pictures, the very fact of acknowledging the future—whether it’s the human future of the next few decades or hundred years, or the deep future in which there will be no evidence of human civilization on Earth’s surface—comes with a great responsibility. A lot of people have described the project as a “time capsule” or a “message for the future,” which is one way to think about it. But I often think about the project as an exquisitely human construction, containing traces of stories, emotions, impressions, and ideas. The object then goes into space, and the pictures—little bits of congealed humanity—then orbit the earth forever, and the pictures will watch the earth transform, evolve, and ultimately end. In this scenario, the pictures aren’t representations or messages so much as little traces of humanity that will watch the earth when we are gone.

NT: Who did you speak with as part of the research for the project? I know that you experienced some resistance from people about the nature of this project in terms of it trying to tackle universal questions. I also know that these conversations have to some degree made you a little concerned that the project will be entirely misunderstood as some big spectacle-in-space project.

TP: Well, I’m not trying to tackle universal questions in this project and I’m not even sure what a universal question would be—and that is actually one of the themes of the project. The germ of this project happened many years ago when I was talking to an amateur satellite spotter named Ted Molczan. I’d asked him whether he had a good algorithm for determining how long it takes for a satellite in orbit to fall back to earth. Molczan pointed me towards a satellite catalog called the Royal Aerospace Establishment Table of Earth Satellites, an old British publication that listed all the (non-secret) spacecraft in Earth’s orbit, along with their orbital characteristics, one of which was the lifetime of the orbit. The catalog has been out of print for decades, but orbits are relatively standardized so if you want to know the orbital lifetime of a recent satellite, you can just find an older satellite in the RAE Table with similar orbital characteristics and the lifespan will be about the same. The vast majority of satellites are in what are called “low earth orbits” at an altitude between 300–1000 kilometers. At these altitudes, satellites slowly accumulate drag from the last wisps of Earth’s atmosphere, and the accumulated drag pulls them back toward earth. For low earth orbiting satellites, it takes anywhere from a few days to about a hundred years for this to happen. As I scanned the tables, I noticed something strange: some satellites, especially geostationary and geosynchronous satellites, had lifetimes listed as “one million years” or “indefinite.” I asked Molczan whether these numbers were correct, and when he told me they were, I realized that these spacecraft will be some of the longest-lasting things humans have ever made, and perhaps will ever make. Molczan agreed, saying he thinks of them as “artifacts.”

When I began thinking seriously about marking one of these future artifacts in some way, I realized that the form of the work could only be a “grand gesture”—i.e. no matter how absurd the idea of making something “timeless” is, the project will inevitably be in dialog with gestures like Steichen’s The Family of Man, or the Voyager Golden Record, a kind of modernist or humanistic meta-gesture the likes of which we’re all able to critique to shreds in our sleep. This terrain is the exact opposite of what’s considered a reasonable framework for a critical artist. But even if the dead satellite in perpetual orbit seems like a dead meta-gesture, its materiality nonetheless persists. And that became a really interesting image to me. So as I began working on the project, I laid out several rules: 1) the project would in no way be a grand “representation of humanity”; 2) instead, the project would be a meta-gesture about the failure of meta-gestures, a collection of images that spoke to the Janus-faced nature of modernity, a story that was not about who the people were who built the dead satellites in perpetual orbit so much as a story about what they did to themselves; 3) this would not be a project that I would do on my own—the project should emerge from a long, sustained series of conversations and interviews with a diverse group of critical thinkers; 4) there would be no representations of humans.

Most of the people I initially approached were very skeptical of the project for understandable reasons. Ignacio Chapella, a brilliant and fiercely critical biologist at UC Berkeley, told me that he didn’t think the project could have any critical value. The author and historian Mike Davis seconded that notion, as did most of the people I talked to, actually. But many were nonetheless game for the ridiculous conversation I was proposing. There are a lot of examples of images in the collection that emerged from these conversations: the entangled bank image emerged out of conversations with Chapella where he was critiquing the bio-engineering paradigm that frames much life-sciences research these days. We talked about the image of the entangled bank in the last paragraph of The Origin of Species—an image of the limits of our ability to understand “life”—as a counterpart of DNA’s double-helix as an ideological representation of the desire to read and master some kind of “book of life.” The “monster function” image came out of a long series of conversations with cognitive scientist and mathematician Rafael Núñez about the ideological notion of mathematics as “universal.” The photograph of Yvonne Chevalier was inspired by Ariella Azoulay’s work on The Family of Man. In addition to these interviews and conversations, I held a research seminar with six research assistants, where we spent the better part of six months scouring archives, looking at and debating thousands of images, and trying to think through what we were doing. A lot of the thought processes and conversations that the images emerged from are recounted in the book.

NT: This work actually works against its very premise, which isn’t exactly the easiest thing to communicate. It is a project that launches into space and is extremely skeptical of the sensibility and emotions that people tend to carry with them when thinking about space. You can’t just remove its colonialist trajectory.

TP: It’s been a real struggle to push against the dominant images of outer space. I think that in the U. S. we’re so culturally conditioned to the narrative of space conquest that a lot of people simply cannot think about space as anything more than some grand colonial expedition to locate and exploit faraway resources and life forms. From the start, the point of the project was to make something that complicated or went against the heroic images of giant rockets hurtling off into the great unknown, or astronauts planting flags on extraterrestrial worlds. I’ve always thought about this project as being quiet, almost sad, and about the dead satellite in perpetual orbit as a twenty-first-century version of Shelly’s “Ozymandias.” A few years ago, I gave a series of talks in which, as an aside, I argued that humans would never colonize other planets—which seems obvious to me because we can’t even “colonize” places like Nevada or South Dakota without massive and ongoing influxes of external resources—and there’s water and oxygen in Nevada and South Dakota, unlike on the moon or Mars. That argument made quite a few intelligent, critical people viscerally angry with me. It was strange—I didn’t even want to announce The Last Pictures until the spacecraft had already been in orbit for a few months. The project is meant to be an alternative to the stupid story about “man’s conquest of the stars.”

NT: It is a project that speaks to people millions of years from now while simultaneously saying that such a notion is impossible and absurd. To flip the condition on its head, perhaps you don’t want a grand gesture in space, but isn’t it really that anyway? You don’t want it to be perceived that you are trying to speak to people in the distant future, but there are, in the end, photos on the disc. You have to sort of nod your head at its potentially being a grand gesture after all.

TP: Yes. The Last Pictures is a paradoxical project. Its theme is paradox and the materials it uses are paradoxical. It is a montage of images whose materiality is such that it will probably last until the sun expands and engulfs Earth in fire and plasma five billion years from now. At the same time, those images are essentially meaningless, not only in the future, but in the present. Very few of the images in the montage “speak themselves” or reveal the things that they gesture toward. The book contains explanatory captions and texts about the images that tell the viewer what they’re looking at; the disc in orbit does not. The Last Pictures is a grandiose gesture that is partly about the suicidal nature of grandiose gestures, but it doesn’t stand outside its own form—it’s not a notional project or a textual critique of another project, it really is a montage of images in orbit for billions of years, and it really will still be there when humans are long gone and the future dinosaurs begin to look up at the night sky.