In social anthropology, we have seen a development away from studies of the so-called old animism, in the traditional sense of E. B. Tylor,1 toward what Graham Harvey has referred to as “the new animism.”2 Central to the approaches of new animism researchers is a rejection of previous scholarly attempts to identify animism as either metaphoric—a projection of human society onto nature as in the sociological tradition of Emile Durkheim3—or as some sort of imaginary delusion, a manifestation of “primitive” man’s inability to distinguish dreams from reality, as in the evolutionary tradition of Tylor. Instead, the scholars concerned—including Philippe Descola,4 Nurit Bird-David, 5 Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, 6 Tim Ingold,7 Morten A. Pedersen 8 Aparecida Vilaça,9 and Carlos Fausto10—each in their own way seek to take animism seriously by upending the primacy of Western metaphysics over indigenous understandings and following the lead of the animists themselves in what they say about spirits, souls, and the like. By “taking seriously,” I simply mean taking seriously what the indigenous people themselves take seriously, which the old studies of animism certainly did not.

In my book Soul Hunters,11 I pushed in the same direction, arguing along phenomenological lines that animist cosmology is essentially practical, intimately bound up with indigenous peoples’ ongoing engagement with their environment. Accordingly, animism is nothing like a formally abstracted philosophy about the workings of the world or a symbolic representation of human society. Instead, it is largely pragmatic and down-to-earth, restricted to particular contexts of relational activity, such as the mimetic encounter between hunter and prey.

This take on animism certainly has its advantages. First, it reverses the ontological priorities of anthropological analysis by holding that everyday practical life is the crucial foundation upon which so-called higher activities of thinking or cosmological abstraction are firmly premised. In addition, it allows us to analyze animist beliefs in a way that is compatible with the indigenous peoples’ own accounts, which tend to be based on hands-on experiences with animals and things rather than on abstract theoretical contemplation. In other words, by going down this phenomenological path we would, for the first time, be able to take seriously the attitudes and beliefs that indigenous peoples have about the nature of such beings as spirits, souls, and animal persons and their relationships with them.

However, while it may at first appear to require no further comment, I want to question the empirical grounds on which anthropologists claim that the indigenous peoples take their own animist beliefs seriously. We may ask whether the new animist studies are overstating the seriousness of the indigenous peoples’ own attitudes toward their spirited worlds. It is exactly here that we begin to glimpse the problem that motivates my writing this article. I am no longer convinced that seriousness as such lies at the heart of animism. Quite the contrary, it seems to me that underlying animistic cosmologies is a force of laughter, an ironic distance, a making fun of the spirits which suggests that indigenous animism is not to be taken very seriously at all.12 I think that we are facing a fundamental yet quite neglected problem here, and I will begin to explore it by drawing attention to a somewhat puzzling episode from my own fieldwork among the Yukaghirs, who are a small group of indigenous hunters living in northeastern Siberia.

Laughing at the Spirits

I should explain that, as with most other arctic and sub-arctic indigenous peoples, the bear is of particular significance for the Yukaghirs. Not because its meat is important in their subsistence economy—they live mainly from hunting the moose—but because the bear is believed to be loaded with an unsurpassed spiritual potency. As Ingold has stated with regard to the attitude of circumpolar peoples in general toward the bear, “Every individual bear ranks in his own right as being on a par with the animal masters, indeed he may […] be [equivalent with] a master” (emphasis in original).13 The fact that the bear, of all the animals, is singled out as especially powerful is perhaps most clearly reflected in the elaborate ritual treatment of its carcass after it has been killed. Hunters generally try to disguise the killing as an unfortunate accident for which they are not to be blamed. They will bow their heads in humility before the dead animal and say, “Grandfather, who did this to you? A Russian [or a Sakha, a neighboring people] killed you.” Before removing its skin, they will blindfold it or poke its eyes out while croaking like a raven. This will persuade the bear that it was a bird that blinded it. Moreover, while skinning the bear they will say, “Grandfather, you must feel warm. Let us take off your coat.” Having removed its flesh, the hunters then deposit its bones on a raised platform, as the Yukaghirs used to do with an honored deceased relative. If the ritual is violated, all sorts of terrible misfortunes are said to be triggered. Yukaghir myths are replete with stories about hunters who fail to obey the ritual prescriptions and lose their hunting prowess as a result, so that the entire camp starves to death.14 Likewise, other narratives describe how a disobedient hunter is violently killed by a relative of the dead bear that seeks bloody revenge for its “murder.”15 It is because of these strict rules of etiquette governing the bear hunt that the following observation came as a complete surprise to me.

I was out hunting together with two Yukaghirs, an elderly and a younger hunter, and they had succeeded in killing a brown bear. While the elderly hunter was poking out its eyes with his knife and croaking like a raven as custom prescribes, the younger one, who was standing a few meters away, shouted to the bear: “Grandfather, don’t be fooled, it is a man, Vasili Afanasivich, who killed you and is now blinding you!” At first the elderly hunter doing the butchering stood stock-still as if he were in shock, but then he looked at his younger partner and they both began laughing ecstatically as if the whole ritual were a big joke. Then the elderly hunter said to the younger one, “Stop fooling around and go make a platform for the grandfather’s bones.” However, he sounded by no means disturbed. Quite the opposite, in fact: he was still laughing while giving the order. The only really disturbed person was me, who saw the episode as posing a serious threat to my entire research agenda, which was to take animism seriously. The hunter’s joke suggested that underlying the Yukaghir animistic cosmology was a force of laughter, of ironic distance, of making fun of the spirits. How could I take the spirits seriously as an anthropologist when the Yukaghirs themselves did not?

I experienced several incidents of this kind which, I must now admit, I left out of my books on Yukaghir animism, as they posed a real danger to my theoretical agenda of taking indigenous animism seriously. One time, for example, an old hunting leader was making an offering to his helping-spirit, which is customary before an upcoming hunt. However, while throwing tobacco, tea, and vodka into the fire, he shouted, “Give me prey, you bitch!” Everyone present doubled up with laugher. Similarly, a group of hunters once took a small plastic doll, bought in the local village shop, and started feeding it fat and blood. While bowing their heads before the doll, which to everyone’s mind was obviously a false idol with no spiritual dispositions whatsoever, they exclaimed sarcastically, “Khoziain [Russian “spirit-master”] needs feeding.” Direct questioning about such apparent breaches of etiquette often proved fruitless. One hunter simply replied, “We are just having fun,” while another came up with a slightly more elaborate answer, “We make jokes about Khoziain because we are his friends. Without laughter, there will be no luck. Laughing is compulsory to the game of hunting.”

Animism and False Consciousness

So what conclusion should we draw from this? Should we say that the Yukaghirs have lost faith in their ancient animist ideology as a result of the longstanding Russian and Soviet impact on their modes of thinking, with the implication that their joking about the spirits reflects a growing lack of belief in them? I don’t think so. Instead, I turn to Slavoj Žižek for inspiration. Ideology, in its conventional Marxist sense, Žižek asserts, “consists in the very fact that the people ‘do not know what they are doing,’ that they have a false representation of the social reality to which they belong.”16 Clearly, this does not apply to the Yukaghirs, as they maintain an ironic distance from their official animist rhetoric and its requirements of treating the spirits with extreme respect. Indeed, it is precisely the discordance between this prescribed ceremonial rhetoric of marked respect and the hunters’ practices of deception and manipulation that the jokes expose and that make them funny. Even so, after a good laugh, the hunters always insist on toeing the line, and they continue to behave according to the prescribed rules of ritual conduct. Thus, the formula proposed by Žižek for the workings of ideology in the cynical and hyper-self-reflexive milieu of postmodernism seems to fit the Yukaghirs as well: “They know very well what they are doing, but still, they are doing it.”17 The Yukaghirs, therefore, are not really naïve animists in the sense suggested by both the “old” and the “new” animist scholars, who assume that indigenous peoples blindly believe in the authority of the spirits. Rather, they know very well that in conducting their ritual activities they are following an illusion. Still, they do not renounce it. But if the Yukaghirs are no hapless victims of false consciousness, but are rather fully aware of the disparity between the rhetoric of spiritual authority and actual practices toward spiritual entities, then we must ask what the importance of such a gap is. In addressing this question, we need to turn to the key principle governing the Yukaghir hunting economy, the principle of “sharing.”

The Dead End of Sharing

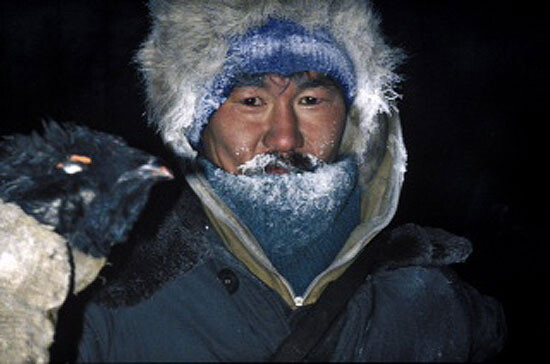

In many respects, the Yukaghir distribution of resources reflects a traditional hunter-gatherer economic model of sharing, in that they run a “demand sharing” principle.18 People are expected to make claims on other people’s possessions, and those who possess more than they can immediately consume or use are expected to give it up without expectation of repayment. This principle of sharing applies to virtually everything, from trade goods, such as cigarettes and fuel, to knowledge about how to hunt, but it applies most forcefully to the distribution of meat: “I eat, you eat. I have nothing, you have nothing, we all share of one pot,” the Yukaghirs say [figure 3].19 The important point for my argument, however, is that Yukaghir hunters engage with the nonhuman world of animal spirits in much the same way as they engage with other humans, namely, through the principle of demand sharing. In the forest, hunters will ask—even demand—that spiritual owners share their stock of prey. They will also address the spirits of the rivers and places where they hunt, saying, “Grandfather, your children are hungry and poor. Feed us as you have fed us before!” In this sense, their animist cosmology could be interpreted as an integrated system, an “all-embracing cosmic principle based in sharing” in which the forest is akin to a “parent” who gives its human “children” food in overabundance, without expecting anything in return, as has been suggested for hunter-gatherer peoples more generally by Bird-David.20 The trouble is that in proposing this argument, Bird-David assumes that the official rhetoric of these hunter-gatherers faithfully corresponds to their activity of hunting. But this is not so—if it were, we would have aligned the Yukaghir with something akin to a “death wish,”21 for surely a community that hunts simply by waiting for the forest to “feed” them, without making any effort to control their prey, would not survive long.

What this points to, then, is that the Yukaghirs’ rhetoric about the forest being a “generous parent” is not meant to be taken too seriously. Rather, it is a sophisticated means of spirit manipulation, which is an inherent, even necessary, part of Yukaghir hunting animism. This becomes evident when we realize that a paradox is built into the moral economy of sharing, which makes it risky—lethal, in fact—to take the principle of unconditional giving at face value.

We have already seen that in a sharing economy people have the right to demand that those who possess goods beyond their immediate needs give them up. With regard to the hunter-spirit relationship, this means that as long as an animal spirit possesses prey in plenty, the hunter is entitled to demand that the spirit share its animal resources with him, and the spirit is obliged to comply with the hunter’s demand. However, if the wealth divide between the two agencies becomes displaced, their respective roles as donor and recipient will be inverted, and the spirit will now be entitled to demand that the hunter share his resources with it, a claim it will assert by striking him with sickness and death. What this points to is that the condition of truly radical sharing with animal spirits is ultimately unsustainable and indeed self-destructive, as it sooner or later ends with the roles of donor and recipient being reversed such that the human hunters fall prey to the spirits of their animal prey. The hunters’ response is to transform the sharing relationship with the spirits into a “play of dirty tricks” (Russian pákostit’), which effectively means turning the hunt into a game of “sexual seduction” by inducing in the animal spirit an illusion of a lustful play [figure 4].22 The feelings of sexual lust evoked in the spirit lead the prey animal to run toward the hunter and “give itself up” to him in the expectation of experiencing a climax of sexual excitement, which is the point at which the hunter shoots it dead. However, after the killing, the animal spirit will realize that what it took to be lustful play was in fact a brutal murder, and it will seek revenge accordingly. The hunter, therefore, must cover up the fact that he was the one responsible for the animal’s death. I have already described this procedure in relation to the bear ritual, where hunters will seek, by means of various tactics of displacement and substitution, to direct the anger of the animal spirit against non-Yukaghirs, humans and nonhumans alike. As a result, the hunter himself will not appear to have taken anything from the spirit, at least not formally, and no sharing relation was therefore ever established between the two. This in turn rules out the spirit’s right to demand the hunter’s soul. In this way, hunters seek to maximize benefit at the spirit’s expense, while avoiding the risk of falling into the position of potential donor. This corresponds in effect to what Marshall Sahlins has called “theft,” which he characterizes as “the attempt to get something for nothing,” and which he argues to be “the most impersonal sort of exchange [that] ranges through various degrees of cunning, guile, stealth, and violence.”23

Not Taking Animism Too Seriously

By way of conclusion, I want to make clear that I do not mean to suggest that through joking, hunters question the reality of the existence of spirits. Rather, their joking reveals that they do not take the authority of the spirits as seriously as they usually say they do or as their mythology tells them to. Joking and other types of ridiculing discourses about spirits play a prominent role in the everyday life of hunters, but not because they entail resistance to or subversion of the dominant cosmological values of the sharing economy. Virtually all Yukaghirs ascribe to the spirit world and the demand sharing principle, and they regard both as immutable and morally just. However—and this is the key point—they are well aware that this system must never become total. For the Yukaghirs, this would stand for “death,” as it would give the spirits the moral right to consume them in a series of divine predatory attacks. To avoid this, hunters must constantly steer a difficult course between two moral realities, transcending the official animist rhetoric of respect and sharing through equally animistic forms of theft, seduction, and deception. In this, the ongoing ridiculing of the spirits plays a key role, for it reminds hunters not to take the complex of myths, beliefs, and rituals too seriously, but instead to carve out an informal space from the official moral discourse of respect and sharing that is marked by the alternative ethos of thievery, with its own moral codex of seduction, trickery, and even murder. Hunters’ playful relationships with the spirits thus allow them to escape from the latent dangers of total spiritual domination. In other words, they are quite serious about not taking the sprits too seriously. Laughing at the spirits is essentially a life-securing practice. Rather than being accidental to animism, laughter resides at the heart of it. If the indigenous animists are not supposed to take their own animist rhetoric too seriously, perhaps anthropologists should follow their lead.

See Edward B. Tylor, Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art, and Custom (London: John Murray, 1958, 1871)

See Graham Harvey, Animism: respecting the living world (London: Hurst & Co.; New York: Columbia UP; Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 2005).

See Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, trans. K. E. Fields (New York: The Free Press, 1995, 1912).

See Philippe Descola, La nature domestique: symbolism et praxis dans l’écologie des Achuar (Paris: Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 1986.)

See Nurit Bird-David, “The Giving Environment: Another Perspective on the Economic System of Hunter-Gatherers,” in Current Anthropology 31 (1990): 183–96.

See Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism,” in Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) 4 (1998): 469–88.

See Tim Ingold, “Totemism, animism and the depiction of animals,” in The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill (London: Routledge, 2000), 111–31.

See Morten A. Pedersen, “Totemism, Animism and North Asian Indigenous Ontologies,” in Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 7.3 (2001): 411–27; Okruga (The Odul (Yukagirs) of the Kolyma Region) (Yakutsk, 1996, 1930.

See Aparecida Vilaça, “Chronically unstable bodies: reflections on Amazonian corporalities,” in Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) 11 (2005): 445–64.

See Carlos Fausto, “Feasting on people: eating animals and humans in Amazonia,” in Current Anthropology 48.4 (2007): 497–530.

Rane Willerslev, Soul Hunters: Hunting, Animism, and Personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007).

See Rane Willerslev and Morten Axel Pedersen, “Proportional Holism: Joking the Cosmos into the right Shape in North Asia,” in Experiments in Holism: Theory and Practice in Contemporary Anthropology, ed. Ton Otto and Nils Bubandt (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010): 262–278.

Tim Ingold, “Hunting, Sacrifice and the Domestication of Animals,” in The Appropriation of Nature: Essays on Human Ecology and Social Relations (Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 1986): 257.

See Lutmila N. Zukova, I. A. Nikolaeva, and L. N. Dëmina, Folklor Yukagirov Verhnei Kolymy (Folklore of the Verkhne Kolyma Yukaghirs) (Yakutsk, 1989), pts. 1–2. Also see Nicolai I. Spiridonov (Teki Odulok), Oduly (Yukagiry) Kolymskogo Okruga (The Odul (Yukagirs) of the Kolyma Region) (Yakutsk, 1996, 1930).

Rane Willerslev, On the Run in Siberia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 67.

Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1989), 31.

Ibid., 29.

Nicholas Peterson, “Demand Sharing: Reciprocity and the Pressure for Generosity Among Foragers,” in American Anthropologist 95.4 (1993): 860–74.

Rane Willerslev, Soul Hunters, 39.

Nurit Bird-David, “The Giving Environment.”

Jonathan Z. Smith, Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982).

Rane Willerslev, Soul Hunters, 89–118.

Marshall Sahlins, Stone Age Economics (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1972), 195.