The following text, which is the final of three installments, traces back to a conversation I had with Mike Kelley in 1994, “Too Young to be a Hippy, Too Old to be a Punk.”1 Christophe Tannert at Kunstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin had invited us to discuss underground political and aesthetic culture in the US for the first issue of Bethanien’s Be Magazin. One year later, I followed this up with a narrative account and analysis of the subject, “Burying the Underground.” Meanwhile, a series of sieges, armed standoffs, and bombings made Americans increasingly aware of a growing polarization between the US federal government and what was hardening into a grassroots militia movement: Ruby Ridge (1992), Waco (1993), Oklahoma City (1995) and Fort Davis, Texas (1997). I began to see this as a right-wing counterpart to militant leftism. In fact, the right seemed to be mirroring tactics that had previously belonged to the leftist underground. This led me to write a complementary essay, “Heil Hitler! Have a Nice Day!, the Politics of Hate in the USA” By 2001, the militia movement had run out of steam. When al-Qaeda terrorists staged the September 11 attacks, however, these so closely resembled events described in The Turner Diaries that I had initially suspected the radical right. Although unemployment and economic dislocation drove the militia movement, the Great Recession has not provoked a similar response. Instead of overturning—or seceding from—the federal government, the far right, now exemplified by the Tea Party, wants to work from within the political system by downsizing government and converting it to a states’ rights model. This shift is evident in the current Republican debates leading up to the next presidential election, where candidates have tried to turn “moderate” into a pejorative term.

—John Miller

***

Posse Comitatus

The Jew run banks and federal loan agencies are working hand-in-hand foreclosing on thousands of farms right now in America. They are in essence, nationalizing farms for the jews [sic], as the farmer becomes a tenant slave on the land he once owned….The farmers must prepare to defend their families and land with their lives, or surrender it all.

—James Wickstrom,2 Christian Identity minister and radio talk show host

Of all the far right factions, the Posse Comitatus may be the largest. A true grassroots movement, it is also the most amorphous and the hardest to pin down. James Ridgeway compares its organizational flexibility with that pioneered by the SDS, yet it also takes the anti-Federalist logic of states’ rights to a topical extreme. “Posse Comitatus” literally means “power of the county” in Latin. The name refers to the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 which forbids the use of US military and national guard forces as civilian police forces.3 Congress passed this legislation after the Civil War to prevent President Grant from using soldiers to guard ballot boxes against election fraud in southern states.4 The Posse Comitatus believes this law empowers a sheriff to call a posse into being or to disband it as necessary. A posse is simply “all the men that a sheriff may call to his assistance in the discharge of his official duty, as to quell a riot or to make an arrest.”5 The Posse Comitatus sees the law as a wellspring of radical decentralization, granting the sheriff ultimate authority. Accordingly, its members consider income tax, social security payments, drivers’ licenses and even license plates as violations of the Constitution. The Posse claims that, when necessary, it may usurp even the sheriff’s authority. According to a doctrine set forth by Christian Identity minister William Potter Gale, the Posse claims its authority comes straight from God.

Although the Posse Comitatus is freeform by definition, Lyman Tower Sargent traces its origin to the Citizens Law Enforcement and Research Committee, founded by former Silver Shirt and Identity Christian Henry L. Beach in 1969.6 With the spate of family farm foreclosures beginning in the late 1970s, ranks of the Posse expanded as farmers withheld taxes and fought to save their property. Amidst the greater period recession, high interest rates combined with a severe drop in demand for crops to touch off a farm crisis. After a major US-Soviet grain deal fell through, rising inflation forced underdeveloped countries to redirect their budgets from grain purchases to debt maintenance. In the US, the small farmer was left holding the bag. What made the crisis even worse was farmland itself sometimes dropped to a third of its previous value. A congressional report estimated that almost half the nation’s 2.2 million farmers would lose their farms by the end of the century.7 Unable to make ends meet, some turned to community activism, some to alcohol and spousal abuse, and others to anti-Semitism. Just as Nazis once blamed Jews for the dislocations of modernization, bankrupt small farmers wanted to pin their troubles on a Jewish banking conspiracy. Few, however, bothered noting that Jews own none of the big, international banks.

The idea of the family farm as a wellspring of American identity runs deep in the United States. It derives in part from Thomas Jefferson, who viewed big cities with distaste and envisioned the United States as a vast array of independent farms:

Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people, whose breasts he has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue.

They are the most vigorous, the most independent, the most virtuous, and they are tied to their country, and wedded to its liberty and interests, by the most lasting bonds. 8

Jefferson’s philosophy reflected the political economy of the southern plantation system in which each plantation produced much or all of what it needed. (The autonomy of the plantation, of course, depended on slave labor.) Jefferson himself owned a Virginia plantation—though, ironically, a not very successful one. Unlike George Washington, he did not free his slaves after the Revolutionary War.9 Conversely, Washington was a land speculator in the trans-Appalachian region and therefore less aligned with small property interests. Jefferson vigorously championed small farming yet, by establishing a liberal political culture within a capitalist economy, his policies paved the way for America’s transition to industrial capitalism.

The small farmer’s aspirations for independent production and land ownership constitute as much an ideal of civic virtue as they do a means of livelihood. Even so, the supposed autonomy of the small farm has always been tenuous at best, subject to the vagaries of good and bad crops, variable interest rates and supply and demand. In other words, the autonomy of the small farmer was always a relative state—one rested on a precarious economic foundation. During bad times, small farmers have often resorted to wage labor to keep their farms intact. Nonetheless, their aspirations mark them as petit-bourgeois and have rarely shown solidarity with labor movements. Moreover, they resent federal farm subsidy programs—not only because policy makers attach them to big agricultural conglomerates, but also because they render the small farmer a dependent consumer instead of a virtuous producer.10 This tension is not new. Frontier farmers often found themselves at odds with a centralized government unwilling—or unable—to protect their interests. Rural vigilante justice and its attendant gun culture are legacies of that history. Taking the law into one’s own hands thus survives as a cherished rural tradition. And yet that civic independence has been frustrated in recent years. American farmers have been forced into the painful admission that the small farm has become inefficient and wasteful relative to conglomerate “agribusinesses.” Here, their sense of civic deprivation, plus very real material losses, goes back to a promise held out by homesteading: land ownership. James Corcoran has described its importance:

Land doesn’t only serve as a farmer’s collateral for operations loans, the ability to buy the seed, fertilizer and chemicals to plant his fields—land is a farmer’s identity. It is his connection to God; it is his religion, his nationality, his family’s heritage, and his legacy to his children. Land is a farmer’s way of life, and in the early 1980s he was losing it. Like the people he replaced on the land—the American Indian—the farmer became a modern exile, forced to migrate to strange cities and states in search of a new life.11

Driving people from the land is part of the process of long-range accumulation that Marx identified as a structural feature of capitalist development. The farmers’ resistance to dispossession does raise the radical question of who is entitled to land ownership. But claiming a holy right to the land—as do the Posse and Identity Christians—is a self-serving ideology; not only does it justify the farmer’s existence against abstract economic forces, it also represses the historical memory of how frontier farmers violently drove their predecessors, the Native Americans, off the very same soil. This manifest destiny of the small farmer simply transmutes the divine right of kings into the rural populist homestead. Even the ideal of independent production can, at times, undercut the small farmer’s sense of social responsibility. Thus, to consider small farming an inalienable and God-given way of life entails reactionary identifications with blood and soil.

Alarmed by an anti-Semitic flare up in the farm belt, in 1986 the Anti-Defamation League commissioned the Lois Harris organization to poll Iowa and Nebraska residents on these issues. Seventy-five percent of the respondents blamed “big international bankers” for farm problems, with 13 percent specifically blaming Jews. 27 percent agreed, “Farmers have always been exploited by international Jewish bankers.” Among people older than sixty-five, that number leapt to 45 percent.12 The growth of the Posse closely followed this trend.

Typical Posse tactics include highly effective forms of “paper terrorism” such as tax resistance and filing nuisance liens and lawsuits, which tie up courts and make life miserable for Posse targets. When these fail, they sometimes turn to guns. In 1980, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) identified 17,222 individuals who, as a form of tax protest, either refused to file returns or filed and refused to pay what they owed. By 1983 that number jumped to 57,754 and subsequent efforts by a special IRS task force have hardly made a dent in this figure.13 In Wisconsin the aforementioned James Wickstrom, onetime candidate for governor and US Senate, openly espoused tax revolt and violence.14 Some groups, like Charles Shugarman’s Virginia Patriots Network, conduct special seminars in tax resistance, stating that wages are a special form of barter between employer and employee and, therefore, not subject to taxation.15 With a similar barter idea, Denver Posse member John Grandbouche initiated a system of warehouse banks where depositors could convert their money to gold or silver to avoid taxes. Grandbouche called his organization the National Commodities and Barter Association (NCBA). The Wall Street Journal reported that the NCBA laundered up to half a million dollars a day for as many as 20,000 depositors. Federal agents raided Grandbouche’s offices in 1985, recovering thousands of documents and an estimated $250,000 in gold bullion. A federal judge, however, ordered the return of this property.16 Other warehouse banks have turned out to be simply old-fashioned bilking schemes in which otherwise skeptical farmers have lost their life savings to con men. In June 1986, for example, authorities convicted Roderick Elliot in one such an embezzlement operation. Elliot was the publisher of the movement’s key tabloid, The Primrose and Cattleman’s Gazette (its name insinuating that Jewish bankers had led farmers “down the primrose path”).17 More recently, Roy Schwasinger’s organization, We The People, sold about 3,000 bogus “information kits” at $300 each to gullible farmers. These explained how to claim one’s portion of a supposed $600 trillion class action suit against the government brought by ranchers and farmers. In 1995 Schwasinger received a nine-year prison sentence for his part in the scam.18

In 1983 the death of the sixty-three-year-old tax resister Gordon Kahl created the Posse’s first martyr. Kahl was a decorated World War II veteran who kept his farm afloat by working winters in Texas as an auto mechanic. He joined the Posse in 1974, stopped paying taxes and appeared on television two years later urging others to follow suit. Going public landed him in Leavenworth prison for one year. Authorities then released him on probation with the proviso that he stay away from the Posse. Unrepentant, Kahl still refused to pay taxes and still urged others to do the same. Although he owed only a pittance, his very public defiance made him a thorn in the side of government officials. On February 13, 1983, federal marshals tracked Kahl, his son and some friends as they were leaving a Posse meeting in Medina, North Dakota. Kahl stopped at the marshals’ roadblock and a gunfight began. The marshals wounded his son. A crack shot, Kahl killed two marshals and wounded three others in retaliation.19 He went on the run for four months, then holed up in the Smithville, Arkansas “earth home” of his Posse friends, Leon and Norma Gintner. This dwelling was a survivalist bunker stockpiled with weapons and food. Federal agents and local Sheriff Gene Matthews surrounded the bunker on June 3. Outside, they captured Leonard Gintner. Shortly thereafter, Gintner’s wife came out to surrender. Neither would confirm whether Kahl was hiding inside. Matthews entered the bunker, hoping that, as sheriff, he could convince the fugitive to surrender peacefully. Kahl fatally wounded Matthews with one round from his Ruger Mini-14. Police experts believe that, in the exchange, Matthews killed Kahl as well. Unsure whether the fugitive was dead or alive, agents proceeded to spray the bunker with gunfire. The assault ended only after a commando detonated the bunker’s more than 100,000 rounds of ammunition with a grenade. Death left Kahl a longstanding hero in the movement.20 It also set the stage for a siege/shootout syndrome that would be tragically repeated as the struggle between right-wing dissidents and the federal government continued to escalate.

Other Posse figures include Arthur Kirk, who died in a 1984 firefight with a Nebraska SWAT team, and the eccentric Michael Ryan. Ryan presided over a polygamous, survivalist compound in Rulo, Nebraska where he forced his male followers to sodomize each other and a pet goat.21 Once considered a leader chosen by God, Ryan was convicted by jurors for torturing and killing two of his followers, twenty-seven-year-old James Thimm and five-year-old Luke Stice. For refusing to sodomize the goat, Ryan shoved greased rake handles up Thimm’s rectum, then literally skinned him alive. When police raided the Rulo compound, they discovered more than $250,000 in stolen farm equipment, an arsenal of full- and semiautomatic weapons and 150,000 rounds of ammunition.22 By anyone’s standards, Ryan was certifiably insane. His example illustrates the individual extremes that become available once the social contract is jettisoned. Conversely, Ryan’s case—among others—raises the question of how violence and irrationality become legitimized, both within extremist cults and within the mainstream.

The Turner Diaries

The great danger of democracy, of course, is the same danger that exists with any other form of government; namely, that the wrong minority will be in the driver’s seat. That’s the problem we must overcome now—or perish as a race.

Before the advent of television, it wouldn’t have been feasible to run a truly progressive nation democratically; the process of control was too awkward. That’s why the United States drifted the way it did, subject to various pressure groups, until the worst of all possible groups elbowed the others aside and took over. These days the process of control is reasonably efficient, and if we ever manage to break the grip of the present media bosses we can look forward to the use of the same process to speed America along the upward path again.

—William L. Pierce 23

The Turner Diaries is an influential right-wing tract written by former physics professor William Pierce. Pierce published it, however, under the pseudonym Andrew MacDonald. Critics call the book the Mein Kampf of American neo-Nazism. Before starting his own National Alliance, Pierce had, in fact, been a member of George Lincoln Rockwell’s American Nazi Party and the John Birch Society. Society president Robert Welch introduced Pierce to an apocalyptic story called The John Franklin Letters that Pierce used as a model for his own book.24 In the guise of a futuristic novel, The Turner Diaries is part propaganda, part primer for guerilla war and part juvenile blood lust. Its publisher Stuart Lyle described it as “an underground classic,” selling more than 185,000 copies outside bookstores before its above ground publication and distribution in 1978. Pierce himself gloats:

It offends almost everyone; Afro-Americans, feminists, gays and lesbians, liberals, communists, Mexicans, democrats, the FBI, egalitarians, and Jews. Especially Jews: for it portrays them as incarnations of everything that is evil and destructive.25

Former liberal William Gayley Simpson laid the ideological foundation for Pierce’s book in his own Which Way Western Man? After working as an integrationist, Simpson became obsessed with the idea that white Christians risked forfeiting their identity through policies of desegregation and affirmative action. These, moreover, he viewed as part of a sinister Jewish plot: a divide-and-conquer strategy of miscegenation that would leave only Jewish racial integrity intact. Consequently, he argued vehemently for eugenics, segregation and the deportation of Jews.26 Even so, Pierce sharply distinguishes between these beliefs and those of Christian Identity which he dismisses as a “lowbrow” theology incapable of attracting anyone but “hicks.”27

The narrative conceit of The Turner Diaries is the belated discovery of a unique record of “the Great Revolution,” the diaries of one Earl Turner, which historians have republished on the revolution’s one-hundredth anniversary. Pierce envisions this event in apocalyptic—rather than political—terms. The struggle occurs in 1999, at the outset of the millennium. Copying the French Revolution, Pierce even sets out a new dating system, with time divided BNE (Before the New Era, analogous to prehistoric time) and the years following it. Nevertheless, Pierce’s revolution is totalitarian, not democratic; the rights of man evaporate before a phantasm of racial purity. He also adds “editors’ notes” as additional commentary to Turner’s firsthand account. This “historicizes” the fantasy, a posture not dissimilar to Kruschev’s boast “History is on our side. We will live to see you buried.”

The plot begins when the federal government passes an anti-gun law called, suggestively enough, the Cohen Act. Blacks begin raping white women in great numbers (one of Pierce’s deep obsessions) and, as special deputies, round up all those who refuse to turn over their guns. Jews, of course, have masterminded this turn of events. Only one group stands ready to resist “the System,” a small network of underground cells called only “The Organization.” Earl Turner belongs to one such cell of four people operating in Washington, DC. Long before the Cohen Act, his group had buried a cache of guns in a remote Pennsylvania woods. Once they retrieve their weapons, they turn to robbery and murder simply to survive; as gun owners, they can neither work nor identify themselves in public. Meanwhile, Congress passes more stringent laws requiring all citizens to carry “internal passports” –used for all transactions from banking to medical care to purchasing gasoline. This pushes the Organization to more extreme measures, culminating in bombing a new supercomputer (for processing internal passports) housed in the FBI’s Washington headquarters. To carry this out, The Organization uses a truck filled with explosive chemical fertilizer. To finance its intensified level of operations, it starts counterfeiting as well. Trained as an engineer, Turner becomes responsible for bombs, communications and counterfeiting.

Soon, Turner’s superiors invite him to join “the Order,” an elite mystical cadre within the Organization. Its grey-hooded members reveal to him that white supremacy is divinely ordained and that Aryan terrorists are “the instruments of God.” As the struggle continues, the Organization’s leaders realize that only the System can win a war of attrition and accordingly step up their approach. In an all-or-nothing effort, they concentrate their entire force in Southern California and, through inside agents, trigger an insurrection within the armed forces stationed there. In the resulting chaos, the Organization manages to establish regional sovereignty, fending off the System by seizing nuclear warheads and threatening to use them. After setting up free zones in major American cities, it nukes Tel Aviv, saving a few remaining missiles for the Soviet Union. This, in effect, kills two birds with one stone, devastating communism and subverting the System’s control in America. The story ends with an inadvertent allusion to Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove”: Turner flying a suicide mission to the Pentagon with a nuclear warhead strapped to his crop-duster. The editorial notes confirm that, because of Turner’s noble sacrifice, the Aryan race successfully purges every other race from the face of the planet. Thus begins the New Era—a cartoon version of xenophobia with pointed consequences for the American political landscape of the 1990s.

Pierce’s hatred of other races is tautological. He accuses others of conspiracy and degradation, when he himself is the worst offender. The Turner Diaries depicts both Jews and African-Americans as stereotypes; Pierce even writes in dialect to further ridicule them. In lieu of social or historical analysis, Pierce invokes God to justify his beliefs. His stance toward the social movements of the 1960s and 70s is wholly reactive:

I remember a long string of Marxist acts of terror 20 years ago, during the Vietnam war. A number of government buildings were burned or dynamited, and several innocent bystanders were killed, but the press always portrayed such things as idealistic acts of “protest.”

There was a gang of armed, revolutionary Negroes who called themselves “Black Panthers.” Every time they had a shootout with the police, the press and TV people had their tearful interviews with the families of the Black gang members who got killed — not with the cops’ widows. And when a Negress who belonged to the Communist Party [a reference to Angela Davis] helped plan a courtroom shootout and even supplied the shotgun with which a judge was murdered, the press formed a cheering section at her trial and tried to make a folk hero out of her.28

“Women’s lib” was a form of mass psychosis which broke out during the last three decades of the Old Era. Women affected by it denied their femininity and insisted that they were “people,” not “women.” This aberration was promoted and encouraged by the System as a means of dividing our race against itself.29

…the knee-jerk liberals have forgotten all about their “radical chic” enthusiasm of a few years ago, now that we are the radicals.30

As a tactician, however, Pierce is coldly logical and utterly clearheaded. For starting a terrorist cell, he advises in the essay “A Program for Survival” (1984) published under his own name, a general three-phase program for Aryan supremacy comprised of:

1. cadre building;

2. community building;

3. community action;

4. make propaganda as militant as possible to attract only the most committed element;

5. operate on a “need to know” basis;

6. communicate either by meeting face-to-face or through short coded messages;

7. separate into “legal” and underground units (like Shin Féin and the I.R.A.);

8. “…[O]ne of the major purposes of political terror, always and everywhere, is to force the authorities to take reprisals and to become more repressive, thus alienating a portion of the population and generating sympathy for the terrorists.”

9. “…[T]he other purpose is to create unrest by destroying the population’s sense of security and their belief in the invincibility of the government.” 31

If the term “community action” sounds benign, however, The Turner Diaries shows just what Pierce means by that.

Pierce’s tactics and ideology would be adopted both by Robert Mathews’ group, The Order, and by Timothy McVeigh. Among other things, they anticipate baiting law enforcement officials to use excessive force and exploiting the overkill as movement propaganda.

Bob Mathews founder of The Bruders Schweigen confronting an anti-racism protester.

The Bruders Schweigen

We just want to be a nameless, white underground.

—Robert Mathews32

Bob Mathews was a man with a mission. As an eleven-year-old boy in Phoenix, Arizona, he joined the John Birch Society. Later he became interested in Robert DePugh’s Minutemen. Mathews then started a group of his own called the Sons of Liberty. He also converted to the Mormon faith.33 Under the guidance of fellow Mormon Marvin Cooley, Mathews became a tax resister. In his 1973 W-4 tax form he claimed ten dependents as a single, unmarried man—by that reducing his tax burden to zero. This improbable claim quickly alerted IRS agents, who soon brought him to trial. There, Mathews had a rude awakening when only one of his militia friends agreed to vouch for him as a character witness. Shortly after this, a second friend killed himself, his wife and another couple in a bitter domestic dispute. Disillusioned, Mathews left Phoenix and resettled in Metaline Falls, Washington.34

After taking an apartment, the industrious Mathews soon managed to earn enough money to purchase and clear his own 60-acre plot of land. He found a wife and seemed to settle down. Eventually, his parents and two brothers, once estranged by his extremist views, moved up to Washington as well. Then, in 1978, after four years of relative calm, Mathews read William Galey Simpson’s Which Way Western Man? which left a deep impression. He learned about William Pierce’s National Alliance. By 1981 Mathews discovered William Butler’s Church of Jesus Christ Christian/Aryan Nations in nearby Hayden Lake. Although he had reservations about Butler, he nonetheless attended Aryan Nations events. Around this time, he conceived the “White American Bastion” by which Aryans would become the racially self-conscious political force of the Pacific Northwest. This idea echoed Butlers “10 percent solution,” except that Mathews felt numbers alone would be enough; he did not, at this time, envision the need for a separate government. To this end, he began advertising his “Bastion” plan in the Liberty Lobby’s magazine, The Spotlight. Ultimately, the ads did not pan out; after all his efforts, only one couple moved there. He increasingly resented the apparent docility of most whites and condescendingly called them “sheeple”—sheep people. He also read and absorbed the lessons of The Road Back, an instruction manual for running an underground terrorist group; Essays of a Klansman by Louis Beam, which laid out a point system of awards for Aryan Warriors; and The Turner Diaries. After this, Mathews established his leadership by confronting rowdy counter-demonstrators at Spokane, Aryan Nations rally. Before long he had assembled a small, but hard-core circle of friends and Aryan Nations members around him. He stressed that the time for talk was over. Now was the time for action. In a bizarre ceremony, each swore a loyalty oath before a six-month-old baby, pledging to secure the future propagation of the Aryan race. Before long, the group was planning armed robberies and counterfeiting schemes.35

On October 28, 1983, World Wide Video, Spokane’s only XXX-rated pornography store, became the group’s first target. After days of talks and building up their nerve, they netted a grand total of $369.10. If serious, they were going to have to play for bigger stakes. That Thanksgiving, unbeknownst to Richard Butler, Mathews’ friend Gary Yarbrough began printing their first counterfeit $50 bills on the Aryan Nations printing press. He had a hard time getting the color right, though. Police picked up Mathews’ right-hand-man Bruce Pierce (no relation to William Pierce) on December 3 when the group tried to pass the phony money. With Pierce in jail, on December 18 Mathews pulled a one-man bank heist in desperation. During his getaway, a dye-pack exploded in the loot bag, staining him and the cash red. He managed to clean most of the $25,952 with turpentine and bailed Pierce out of jail. The gang continued to rob banks and restaurants, but soon graduated to armored cars. They set up a system under which they would “tithe” most of the stolen money to other racist groups, setting aside part for their own operation and dividing the remainder as “salaries.” Several men quit their day jobs and began to think of themselves as revolutionaries. With their stolen money, they began to build up an arsenal.36

Meanwhile Pierce had, on his own initiative, ineffectually bombed a Boise synagogue. This breach of security enraged Mathews, but their troubles were just beginning. Aryan Nations member Walter West had begun to spout off in local bars about a new white guerilla group. West also had a reputation for beating his wife, Bonnie Sue, and Order member Tom Bentley had taken a romantic interest in her. Mathews directed Bentley and three others—James Dye, Randy Duey and Richard Kemp—to kill West. Sunday, May 27, 1984 Kemp and Duey brought the unsuspecting West to a remote logging road in the Kaniksu National Forest where Dye and Bentley waited hiding, having already dug a grave. Coming from behind, Kemp struck West’s skull with a three-pound sledgehammer. When this failed to kill him, Duey finished him off with his own Ruger Mini-14 automatic rifle. After that, Bentley moved in with Bonnie Sue; Mathews also began keeping a mistress of his own, Zillah Craig.37 West was neither black nor Jewish, but his murder marked a turning point. The Order had crossed over into lethal violence.

Outspoken radio talk show host Alan Berg specialized in agitating racist listeners. He could be rude, arrogant and insulting, but he was a man of conviction. With his program commanding more than 10 percent of the Denver audience, he nonetheless regarded his provocations as mostly show business. Not so Bob Mathews. He made Berg Number Three on his hit list—after Morris Dees, co-founder of the Southern Poverty Law Center, and Norman Lear, acclaimed television producer and liberal political activist.38 When Mathews stated that the time had come to “take out” Berg, opinion was split within the group. Some felt they were not yet ready, but Mathews refused to wait. His goal was to start a race war; if he were martyred in the struggle, the propaganda would be invaluable. When Mathews asked for volunteers, Bruce Pierce demanded to be the triggerman. Pierce pictured himself as “a true Aryan Warrior.” According to Louis Beam’s “point system,” one needed a full point to become this. Killing a Jew (i.e., Berg) was worth one-sixth of a point; killing the US President was worth one full point. At 9:20 p.m. Monday, June 18, 1984, Pierce gunned down Berg in his driveway as he was climbing out of his Volkswagen Beetle. David Lane and Mathews watched from a Plymouth parked nearby. Detectives quickly found .45 caliber shells from the 12 rounds that riddled the victim’s body. This was no ordinary slaying: the killer clearly wanted to “send a message” to the public. Based on the shells and slugs, investigators quickly identified the murder weapon as an Ingram MAC-10 machine pistol, a weapon of choice for right-wing gun buffs.39 Investigative Division Chief Don Mulnix therefore wasted no time in calling the Colorado Bureau of Investigation, the FBI and the BATF in on the case.40

Again desperate for cash, Mathews planned the Order’s next heist. Thanks to a disenchanted Brinks Company employee, he learned of a regularly scheduled truck—often loaded with millions of dollars—that took an especially vulnerable route north of Ukiah, California. Mathews put together a crew and thanks to careful planning by newly recruited Richard Scutari, pulled off the heist without a hitch. This time they netted $3,800,000. The only problem was that Mathews left behind a pistol registered to his follower Andrew Barnhill. Before long, federal investigators had tied the robbery to the Berg slaying. Their prime suspects belonged to the Order. Meanwhile, Mathews promptly tithed much of the take to his favorite charities: Richard Butler’s Aryan Nations, William Pierce’s National Alliance, Frazier Glenn Miller’s Carolina Knights of the KKK, Louis Beam, Tom Metzger’s White Aryan Resistance, Bob Miles’ Mountain Kirk and Dan Gayman’s Church of Israel.41 With the FBI closing in, he set his sites on the next target: Morris Dees. His preliminary plan called for kidnapping and interrogating Dees, then flaying him alive.42 He also tried to contact the Syrian government to fund his war against the Jews.43 Finally, he gave his group a provisional name, taken from a book about Hitler’s Waffen SS: Bruders Schweigen, which refers to “the Silent Brotherhood.”44

On October 1, 1984, Tom Martinez went on trial at the US District Court in Philadelphia. Martinez was charged with helping pass the Order’s counterfeit bills. Shortly before the hearing, his attorney warned him that the FBI had already linked the Order to the Berg slaying and the Brinks heist. Martinez lost his nerve and turned state’s evidence.45 Based on his tips, the FBI stepped up its manhunt, nearly apprehending Mathews and key member Gary Yarbrough twice. Mathews found safe houses for the Order on Whidbey Island in Puget Sound. On October 23 Martinez led FBI agents to the Capri Motel in Portland where he was to meet Mathews and Yarbrough—ostensibly to discuss the Dees kidnaping. They caught Yarbrough, but Mathews got away, his right hand wounded.46

The Order regrouped on Whidbey Island. Knowing things were at an end, Mathews drafted a declaration of war on ZOG and an Aryan Declaration of Independence, which newspapers in every state were to receive. The Bruders Schweigen would no longer remain underground. The end, however, was nearer than Mathews could have ever known. On December 4, the FBI received an anonymous tip that Mathews and a dozen others had gone to Whidbey. Alan Whitaker, special agent-in-command at the Seattle FBI office, quickly assembled SWAT teams, a Hostage Rescue Team and reserve agents. By Friday, December 7, he deployed them around the Order’s three safe houses and evacuated nearby local residents. In the first house Randy Duey gave up without a fight. Next, counterfeiting expert Richard Merki surrendered with his wife Sharon and an older woman, Ida Bauman. Merki had taken care to burn as much evidence as possible before giving up. Meanwhile, in the third house Mathews refused to respond to negotiators. The FBI then brought in Duey and Merki who urged him to surrender. Mathews, however, demanded that Idaho, Washington and Montana be set aside as an Aryan homeland before he would talk. Meanwhile, his partner, Ian Stewart, gave up, but refused to confirm whether Mathews still had women or children inside with him. Next SWAT teams forced their way in, but Mathews sprayed them with machine-gun fire from above, shooting through the floorboards. They retreated. The following day the FBI brought a helicopter to hover above the house; Mathews sprayed it through the roof. At 6:30 p.m., the FBI command post issued orders to lob M-79 Starburst flares into the besieged building. Within twenty minutes the house went up in a firestorm. Sunday morning, investigators, sifting through the debris, found Mathews’ charred remains next to a blackened bathtub.47

The federal government’s case against the Order had become the government’s biggest since the Symbionese Liberation Army kidnaped Patty Hearst. In the wake of Mathews’ death, the group itself dissipated, but its influence did not. Seattle US District Attorney Gene Wilson put together a massive racketeering case against the remaining members, consisting of sixty-seven separate counts. On April 12, 1985, a federal grand jury indicted twenty-four members on racketeering and conspiracy. When the trial began that September, twelve pleaded guilty. Prosecutors convicted ten more that December 30. After police captured Richard Scutari in March 1986, he too pleaded guilty. In spring 1988, the government sued ten of the movement for sedition, including the leaders Richard Butler, Bob Miles and Lois Beam. This jury, however, acquitted everyone.48 After these events, William Pierce declared that America was not yet ready to embrace the revolution he had outlined in The Turner Diaries. He instead bought up enough American Telephone and Telegraph (ATT) stock to force a corporate phase-out of ATT’s affirmative action policy.49 Pierce’s renunciation of terrorism, however, was disingenuous, simply part of his strategy to separate the movement into underground and aboveground wings.

In the end, Robert Mathews succeeded in becoming the kind of martyr figure that Pierce deemed necessary for a popular revolution. Gordon Kahl had come first, but he was a lone individual. There had been other paramilitary groups too, like the Covenant, the Sword and Arm of the Lord (CSA) or Frazier Glenn Miller’s Confederate Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.50 Yet these functioned more like gangs of thugs, while Mathews’ Order quickly developed into, a model terrorist cell. Although Mathews had even drawn recruits from these other groups, he was the one who managed to take them from talk to action.

Ruby Ridge

In 1989 at an Aryan World Congress meeting, a biker identifying himself as Gus Magisono befriended former Green Beret Randy Weaver. Since his time in the military, Weaver had adopted Christian Identity beliefs and moved his family to an isolated cabin near Naples, Idaho. Overlooking Ruby Creek, the news media later came to call this place Ruby Ridge.

That fall, when Weaver was almost broke, Magisono encouraged him to sell sawed-off shotguns to right-wing militants.51 After Weaver sold his first two, “Magisono,” a.k.a. Kenneth Fadeley, identified himself as a federal operative and threatened to turn him in unless he agreed to spy on Aryan Nations meetings. The FBI had promised Fadeley a reward if Weaver either complied or was arrested. In short, the US government had entrapped Randy Weaver.

Weaver, however, refused and warned Aryan Nations of the plan.52 In turn, the federal government indicted Weaver on firearms charges in December of 1990 and arrested him the following January. He posted a $10,000 bond and was released. The BATF set a court date for February 20 but sent Weaver a summons dated March 20. Six days before he thought he was supposed to appear in court, Assistant US Attorney Ron Howen issued a warrant for his arrest.53 March 20, however, came and went; Weaver ignored the summons and stayed holed up in his cabin.

August 21, 1992, six US marshals, part of a SWAT-like team called the Special Operations Group, surrounded the cabin on Weaver’s isolated twenty-acre property. They kept clear of the house itself for fear of being seen. One marshal threw pebbles near the cabin to distract Weaver’s dog. It started barking. Weaver, his fourteen-year-old son Sammy and a friend, Kevin Harris, grabbed their guns, thinking the retriever had found game. They followed him as he chased the marshals. Randy Weaver split from the others and, spotting a figure in camouflage gear, shouted a warning and ran back to the cabin. As the others began to follow, Marshal Art Roderick shot the dog. Sammy Weaver shot back. Then he continued running. After another burst of gunfire from the concealed marshals, Sammy Weaver fell to the ground dead, shot in the back. Harris returned fire. That exchange left veteran Marshall William Degan dead. It remains unproven exactly who shot whom in this exchange, but clearly Ron Howen had prematurely authorized use of excessive force to arrest Randy Weaver.54

The remaining five officers immediately contacted the US Marshals Service in Washington, DC, which in turn called in the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The FBI mobilized its crack Hostage Rescue Team, headed by Richard Rogers. It brought in agents from around the country. By the day’s end, Idaho governor Cecil Andrus had called a state of emergency, by that authorizing the use of both the National Guard and state militias to capture Weaver. The next day, about four hundred military and police specialists had converged on Ruby Ridge with a helicopter, “humvees” (a military vehicle used in “Desert Storm”), armored transport and personnel carriers, and communications equipment. This force blockaded the Weaver’s property. Rogers had drawn up special “Rules of Engagement” for the operation, authorizing agents to shoot any adults carrying weapons on sight.55

About 6:00 p.m. that day, Weaver finally decided to venture out to reexamine his dead son, whom he had carried to a small shed near the cabin. Harris and Weaver’s daughter Sarah came with him. As he tried to enter the shed, a bullet ripped through the soft flesh under his arm. All three ran back to the cabin. Vicki, Weaver’s wife, held open the door, a baby in her arms. As they raced inside, a federal sharpshooter’s bullet passed through Vicki Weaver’s head, killing her instantly and severely wounding Harris.56 Fearing for their lives, Harris and the remaining Weavers refused to go outside for the next nine days. During this time Harris’s condition grew critical. By the barricades, a hundred local residents kept a vigil for those trapped inside and began to protest the paramilitary assault. Finally, Weaver agreed to surrender only after another former Green Beret, Bo Gritz, and a local Baptist minister, Chuck Sandelin, assured him that he and his family would go unharmed. 57

About one month later, Randy Trochmann, Chris Temple (publisher of a Christian Identity newspaper, The Jubilee) and several others who stood vigil during the siege formed a group called United Citizens for Justice. They proposed to expose government abuse of power and to form chapters in every state to protect fellow “patriots.” The organization, however, fell apart after only a few months.58 Another, more ominous organizing effort followed. This meeting, called “the Rocky Mountain Rendezvous,” took place on October 22 at Estes Park, Colorado. Besides Trochmann and Temple, Louis Beam, Richard Butler and other prominent members of the patriot movement attended.59 Their purpose was to mobilize the far right in the wake of Ruby Ridge. To do so, they decided to focus on anti-government sentiment and to downplay racism, which had been too divisive. As they re-prioritized Jews and blacks as “secondary” enemies, euphemisms replaced racist epithets in movement propaganda. In this, they took their cue from David Duke’s successful campaign for the Louisiana legislature. Identity pastor Pete Peters observed:

Men came together who in the past would normally not be caught together under the same roof, who greatly disagree with each other on many theological and philosophical points, whose teaching contradicts each other in many ways.60

All agreed that they must take extreme measures to check the tyranny of the federal government. Beam stated:

When they come for you, the federals will not ask if you are a Constitutionalist, a Baptist, Church of Christ, Identity covenant believer, Klansman, Nazi, home schooler, Freeman, New Testament believer, [or] fundamentalist….those who wear badges, black boots, and carry automatic weapons, and kick in doors already know all they need to know about you. You are the enemy of the state.61

They concluded that small, unorganized armies would be the most effective countermeasure. Thus, the contemporary militia movement was born. As Morris Dees notes, “At Estes Park, the movement changed from a disparate, fragmented group of pesky—and at times dangerous—gadflies to a serious armed political challenge to the state itself.”62

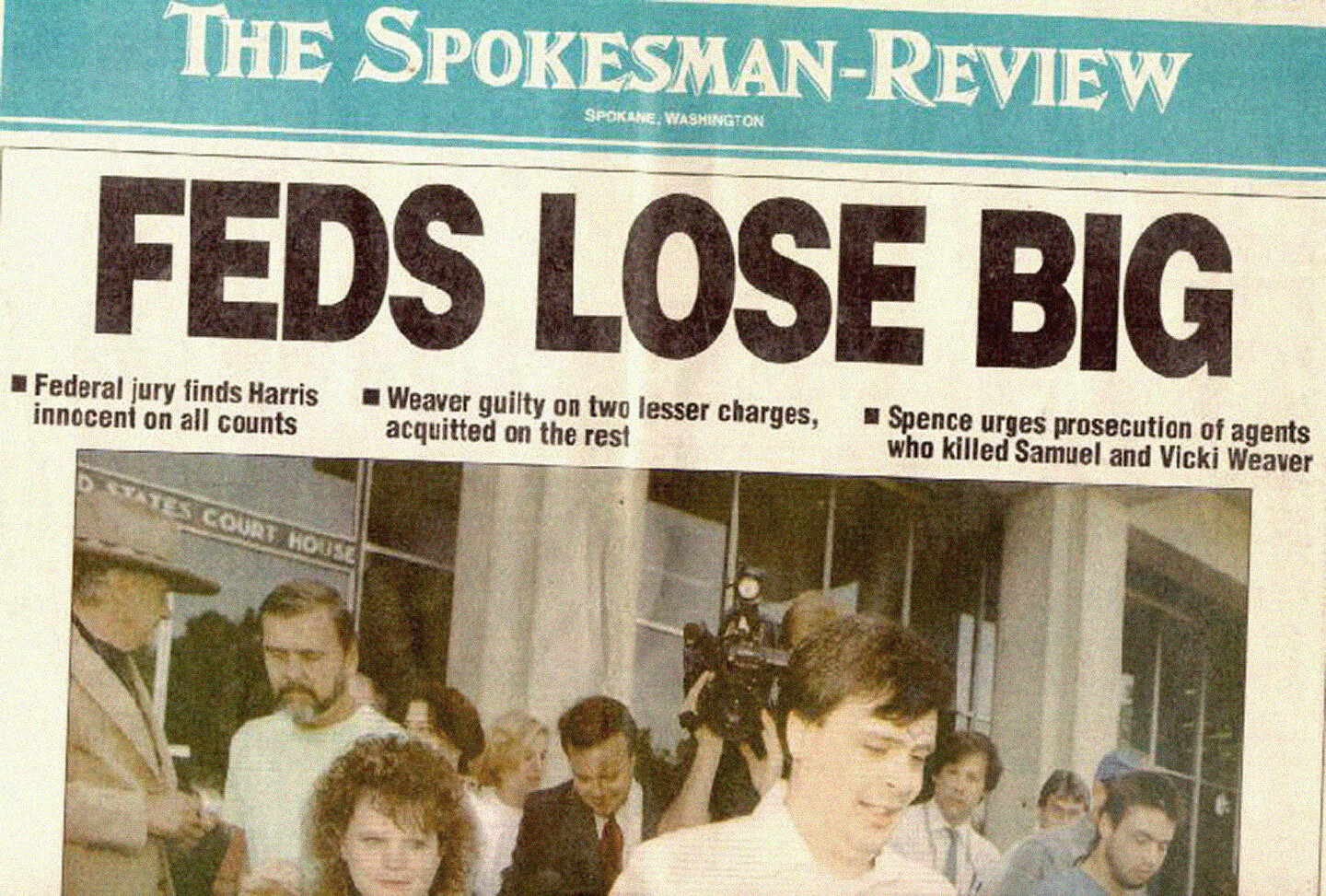

Ron Howen later tried to prosecute Weaver and Harris. The jury, however, in what The New York Times called “a strong rebuke of force during an armed siege,” acquitted the two of all the serious charges: murder, conspiracy and aiding and abetting. They found Weaver guilty only of failing to appear in court and violating the terms of his bail.63 The Weaver family and Kevin Harris later filed a wrongful death and civil rights lawsuit against the federal government. On August 16, 1995, Attorney General Janet Reno announced that the Justice Department had reached a $3.1 million settlement with the Weavers. Yet the government, as customary in such cases, admitted no wrongdoing.64 Under a government probe, however, E. Michael Kahoe, who supervised the siege for the FBI, admitted shredding documents detailing the shoot-to-kill orders.65 Clearly the FBI and the BATF, under the Clinton administration, had overstepped their authority to such an extent that extremist warnings of a nascent police state began to seem credible. Tactically, the encounter furnished the far right with invaluable propaganda. Even so, just as the Weaver case was being tried, the BATF blundered again—with even more horrible consequences.

Waco

On April 19, 1993, the FBI and the BATF launched a concerted, paramilitary assault on a heavily armed and fortified compound in Waco, Texas. They used gas, tanks, and helicopters to incinerate and destroy a complex that belonged to the Branch Davidian religious group and had been under siege for 51 days. When the government ended the siege, they had killed Branch Davidian leader David Koresh and seventy-five of his followers. Of these, all but nineteen were women and children.66

Branch Davidians grew out of Victor Houteff’s Shepherd’s Rod Church in the 1960s. Shepherd’s Rod was a Seventh Day Adventist church; Adventists believe in the “Second Coming” of Jesus, which entails the fiery, apocalyptic destruction of the earth from which only true believers will be spared. After her husband and Branch Davidian founder, Ben Roden, died in 1978, Lois Roden became the new prophet, pronouncing that the Holy Spirit was female.67

David Koresh was born as Vernon Wayne Howell on August 17, 1959. He joined the Davidians in 1981, moving to the Mount Carmel Center. Howell became popular with the other Davidians and by 1984 began to emerge as the sect’s new spiritual leader. This led to a dispute with Lois Roden’s son George who ejected Howell from Mount Carmel. Many other Davidians followed him and set up a community on rental property in Palestine, Texas. In 1985 Howell visited Israel where he claimed to have a visitation from God who instructed him to study and to teach the prophecy of the Seven Seals from the Book of Revelations. During the same period, he also claims God told him to create a “House of David,” in which many wives would bear his children. His offspring would become the rulers of a new, purer world. Although the Davidians were apocalypticists, they were not racists like Christian Identity adherents; the congregation was racially and ethnically diverse.

After his mother’s death, George Roden challenged Howell’s leadership of the new group. He went so far as to dig up a coffin at Mount Vernon, daring Howell to raise the corpse inside from the dead. A gunfight resulted after Howell snuck onto the property to photograph the coffin. US District Judge Walter A. Smith sentenced Roden to six months in jail after Roden had threatened to infect him with herpes and AIDs. With Roden out of the way, Howell urged the country to put a lien on Mount Carmel for sixteen years of unpaid back taxes. By paying these off, Howell legally regained possession of Mount Carmel on March 22, 1988. In 1990 he changed his name to David Koresh, after the Old Testament King David and Cyrus, the Persian king who freed the Jews in Babylon.68

When Koresh declared in 1989 that God had commanded him to take the sect’s married women as his wives, follower Marc Breault became angry and left the group. In a 1990 affidavit he described Koresh as “power-hungry and abusive, bent on obtaining and exercising absolute power and authority over the group.” He took up the role of “a cult buster” and encouraged over a dozen Davidians to sign affidavits against Koresh. The charges included statutory rape, tax fraud, immigration violations, illegal weapons possession and child abuse. In 1991 Breault informed David Jewell that his young daughter Kiri would soon be eligible to become one of Koresh’s many wives. Jewell sued for custody in January 1992 and Jewell’s estranged wife surrendered the child voluntarily.69 In October of that year a Waco Herald-Tribune reporter contacted Assistant US. Attorney Bill Johnson about an exposé he was writing about Koresh, called “The Sinful Messiah.” It would detail the Davidian’s alleged child abuse and arms buildup.70

The BATF felt pressured to take action at Waco. On one hand, Jewell and the local media had raised charges of child abuse within the compound; on the other, due to charges of inefficiency, racism and sexism—not to mention the Ruby Ridge debacle, the BATF faced possible budget cuts and reorganization. Clear and decisive action at Waco might clear up both problems at once. Instead what resulted was a fifty-one-day siege that cost the lives of four BATF agents and that culminated in the death seventy-six Branch Davidians. As in the Ruby Ridge incident, the FBI failed to follow standard agency rules of engagement. Instead, after Davidians shot one marshal, agents received orders to shoot on sight. Reports suggest that although the Davidians were heavily armed, they would have complied with regularly served search warrants—as they indeed had done in the past. By beginning with a siege, the FBI and the BATF may have unnecessarily escalated the entire confrontation. FBI Director Louis J. Freeh later suspended Larry Potts and reprimanded dozens of other federal employees for the botched standoff at Ruby Ridge.71 Potts had overseen both Ruby Ridge and Waco. After this outcome, popular resentment ran deep. In a fund-raising letter, the otherwise mainstream NRA characterized BATF agents as “jack-booted government thugs” who wear “Nazi bucket helmets and black storm trooper uniforms.” That letter caused President George Bush to resign his NRA membership, stating, “Your broadside against federal agents deeply offends my own sense of decency and honor, and it offends my concept of service to my country.”72 In response to both Waco and Ruby Ridge, in October 1995 Janet Reno set forth new rules of engagement procedures for all federal law enforcement. These directives restrict the use of deadly force to a last resort and prohibit changes, even under extenuating circumstances.73

Right-wing propagandists were quick to exploit Waco—notably Linda Thompson. Calling herself “Assistant to the US Commanding General NATO” with a “Cosmic Top Secret/Atomal Security Clearance,” Thompson produced an inaccurate and misleading two-volume video set on the massacre called “Waco: the Big Lie.”74 Ironically, because of “race mixing” many of Thompson’s supporters would have otherwise targeted the Davidians themselves. White supremacist Timothy McVeigh nonetheless used Waco to justify the Oklahoma City bombing.

Oklahoma City

On April 19, 1995, a truck bomb exploded at Oklahoma City’s Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, killing 168 people and wounding about 500 others. As for loss of life and sheer destruction, this was by far the worst terrorist action in US history to date. Nineteen of the victims were children, most from the building’s day care center. In the wake of the World Trade Center bombing, the Clinton administration was quick to blame Arab terrorists, but then had to retract this accusation as it became clear the perpetrators were, after all, American. As in The Turner Diaries, the bomb consisted of ammonium nitrate fertilizer and fuel oil; the target was a building used by the FBI. One Aryan Nations group had already targeted the Murrah building in 1983. A key member of that group, in fact, was Richard Wayne Snell, executed in Arkansas on the very day of the 1995 bombing.75 Before his death, Snell warned, “Look over your shoulder, justice is coming!”76

Shortly after the bombing, a state trooper stopped a yellow Mercury sixty miles outside Oklahoma City to check a missing license plate. He arrested the driver after finding a Glock semiautomatic pistol and a five-inch hunting knife inside the car. The driver turned out to be Timothy McVeigh, a twenty-seven-year-old veteran who had received a Bronze Star in operation Desert Storm. With an identification number from a mangled axle found in the wreckage, investigators soon linked McVeigh to the bombing. They traced the axle to a Ryder truck from Elliott’s Body Shop in Junction City, Kansas. Shop owner Eldon Elliott identified McVeigh as the man who had rented the truck on April 17. The FBI found McVeigh’s fingerprints on fertilizer receipts as well. Other evidence suggested that the brothers James and Terry Nichols may have been involved as well. Once in police custody, McVeigh said little, conducting himself like a prisoner of war.77

The radical right, in fact, had earmarked April 19 as a symbolic date. The Militia of Montana (MOM) called for a “national militia day” to commemorate not only Snell’s execution but also the Waco tragedy.78 Telephone records show that McVeigh called William Pierce’s unlisted telephone number in West Virginia one week before the bombing.79

McVeigh went to trial on April 24, 1997 in Denver, Colorado. Michael and Lori Fortier, the prosecution’s chief witnesses, recounted how McVeigh had diagrammed his plan on their kitchen floor with soup cans six months before the bombing. On June 3 the jury found McVeigh guilty of conspiracy, two bombing charges and eight counts of murder for the federal agents killed in the blast. During the penalty phase of the trial, McVeigh’s defense team changed its tactics. Instead of insisting on McVeigh’s innocence, they stressed his outrage at the Waco massacre, as a justification for taking 168 lives. Morris Dees, however, disputes the far right’s putative “eye for an eye” logic:

The fact that lives were lost during both the Waco debacle and the Weaver incident does not make those tragedies morally equivalent to the Oklahoma City bombing as the militias have suggested. Viewing the Waco incident from the perspective of the government’s complicity, the deaths were by accident. Viewing the Oklahoma City disaster from the perspective of the bomber’s responsibility, the deaths were by design. And even if one were to buy the thoroughly discredited militia line that the government started the blaze that engulfed the Davidians, a crucial distinction would still remain. The FBI pleaded with Koresh and the Davidians to come out of their compound for fifty-one days. The Oklahoma City bombers struck without warning.80

McVeigh received the death penalty on June 13. He remained stoic as he heard the verdict and, leaving the courtroom, flashed the “victory sign” to his family. He was executed on June 11, 2001. Terry Nichols went to federal trial on September 29, 1997. Unlike McVeigh who received a sentence of life imprisonment after the jury deadlocked on the death penalty. For this reason, Nichols was tried again by the state of Oklahoma—which had declined to prosecute McVeigh—in 2004. That jury also balked during the death penalty phase and, for 161 counts of murder, Nichols received an equal number of consecutive life sentences without possibility of parole.

The Militia Movement

Before the Oklahoma City bombing, few Americans knew of the militia movement. Suddenly, Ted Koppel’s Nightline, The New York Times, The Washington Post and Time magazine all featured stories about it. For the first time, the mainstream public heard eccentric figures clad in camouflage gear warn of black helicopters, an invading strike force of Nepalese Gurkhas, secret tracking devices installed in their car ignitions, and the construction of massive crematoria in Minneapolis, Indianapolis, Kansas City and Oklahoma City. All of this was supposedly the work of a global secret government that had even orchestrated the Oklahoma City bombing as a pretext to crack down on Patriot groups. Richard Abanes assessed the movement shortly thereafter:

This loosely knit network of perhaps 5 to 12 million people may be one of the most diverse movements our nation has ever seen. Within its ranks are college students, the unemployed, farmers, manual laborers, professionals, law enforcement personnel and members of the military….Interesting, patriots have no single leader. The glue binding them together is a noxious compound of four ingredients: (1)an obsessive suspicion of the government; (2) belief in anti-government conspiracies; (3) a deep-seated hatred for government officials; and (4) a feeling that the United States Constitution…has been discarded by Washington bureaucrats.81

Reporters have described the militia trend as paranoid. It is largely an expression of middle-class rage—not of the broad middle class itself, only a tiny, disaffected extreme. Since the onset of the Reagan Revolution, .5 percent of the population has consolidated its hold over almost 40 percent of total national assets. With the gap between rich and poor turning into a gulf, the middle class has seen its incomes shrink and its prospects for a higher standard of living disappear. It is further enraged by economic agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the Mexican “bailout.” It views gun control and environmental restrictions as government “meddling” in their private affairs. Many militia members are “weekend warriors” who simply enjoy dressing up and marching around; others, of course, fully intend to use their weapons.82

Robert DePugh’s Minutemen, formed in the early 1960s, were the first contemporary, paramilitary group. Nonetheless, it was Ruby Ridge which gave birth to a national militia movement. During the standoff, sympathizers and local citizens had gathered outside the Weaver property to protest the government’s handling of the case. The resulting negotiations threw Bo Gritz into the limelight; after the Weaver incident, his Specially Prepared Individuals for Key Events (SPIKE) program took on a bigger role in training militia groups. Meanwhile, Louis Beam introduced the idea of leaderless resistance at the Rocky Mountain Rendezvous in Colorado. Beam argued that the patriot movement imitate “the communists”; it should discard traditional, military “pyramid structure” in favor of small, independent cells, impervious to infiltration by federal agents.83 Other protesters formed the United Citizens for Justice in October 1992 to protect citizens from “overzealous government.” That organization soon fizzled, but one member, Randy Trochmann, moved back to Noxon, Montana to form the Militia of Montana (MOM) with his father, Dave, and his uncle, John. The Trochmanns all have ties to Christian Identity. Unlike other militia groups, MOM concentrates on publishing training and propaganda material.84 Its titles include the M.O.D. Manual (a home guide to guerilla warfare), The Road Back (reclaiming America from the New World Order) and the instructional video Invasion and Betrayal (a survey of New World Order conspiracies). MOM members have had armed encounters with local police, but their primary significancy has been to spread the “militia gospel.”85

The Michigan Militia, founded by Norman Olson and Ray Southwell, is one of the movement’s best known. Six months after it was founded in 1994, brigades had sprung up in sixty-three of the state’s eighty-three counties. National attention focused on the Michigan Militia when investigators learned that suspects in the Oklahoma City bombing may have attended the group’s meetings. University of Michigan janitor Mark Koernke (“Mark from Michigan”) is the militia’s chief propagandist. He inveighs against the Federal Management Agency (FEMA) as a wing of the “shadow government” and has produced a two-hour video America in Peril: a Call to Arms that outlines the whole gamut of current conspiracy theories. In keeping with “need to know” tactics, most other militia groups prefer to operate in relative secrecy. Daniel Junas described how militia ideology differs from region to region in Covert Action Quarterly:

the militias vary in membership and ideology. In the East, they appear closer to the John Birch Society. In New Hampshire, for example, the 15-member Constitution Defense Militia reportedly embraces garden variety U.N. conspiracy fantasies and lobbies against gun control measures. In the Midwest, some militias have close ties to the Christian right, particularly the radical wing of the anti-abortion movement. In Wisconsin, Matthew Trewhella, leader of Missionaries to the Preborn, has organized paramilitary training sessions for his church members.86

Claiming that the New World Order controls 50 percent of the United States, US Representative Helen Chenoweth (Idaho) has lent official credence to such otherwise crackpot theories. In line with so-called Wise Use doctrine she also declared “spiritual war” on environmentalism and introduced a bill requiring all arms-bearing federal agents to obtain permission from local sheriffs before entering a state.87 Tactical anti-environmentalism began in Catron County, New Mexico with the Country Rule program. Here, attorney James Catron succeeded in passing an ordinance that declared that the country government supersedes federal law, including such questions as whether cattle may graze on federal lands. With this precedent, some 100 more western counties have followed suit.88

The biggest militia confrontation to date came in March 1996 when members of a group calling itself the Montana Freemen planned to kidnap and execute a judge and a second government official. Previous Freeman actions had included tax resistance, counterfeiting and impersonating government officials. FBI agents intercepted two members who were bringing a truckload of weapons from North Carolina to a compound they called “Justus Township” near Jordon, Montana. After this, sixteen other members, lead by Russell Dean Landers, holed up in this community for what would become an 81-day siege, the longest in American history. During that time, a total of 633 agents worked in twelve-hour shifts with sometimes as many as 150 agents surrounding the compound. After Ruby Ridge and Waco, FBI director Louis J. Freeh had decided to exercise extreme caution. Only after seventy-one days, did the FBI cut electrical power to the compound. Some criticized the agency for wasting time and money, but this approach paid off on June 13 when the FBI ended the armed standoff with no loss of life. Freeh declared, “The message that comes out very clear to everybody—if you break the law, the United States government will enforce the law. It will do it fairly but firmly.” Attorneys Kirk Lyons and David Holloway from the CAUSE Foundation in North Carolina will represent the Freemen in court. The CAUSE Foundation calls itself a civil rights organization for right-wing activists. Randy Trochmann declared that the trial would provide an ideal platform for militia propaganda.

Although the federal government made egregious mistakes at the Ruby Ridge and Waco sieges, these were exceptions. Nonetheless, the far right has aggressively exploited these events, turning its criminals into heroes. This might tempt Americans to forget that law enforcement officials have routinely risked and lost their lives to keep otherwise unregulated paramilitary groups in check. No one has turned the dead BATF or FBI agents into martyrs. Morris Dees notes that no other country in the world tolerates private armies that build bombs and train with assault weapons; local police seldom enforce state laws that forbid these armies.89 Moreover, he warns of a racist component in the tolerance extended to these groups:

It would be interesting to see the reaction of the state attorneys general if the militia groups operating today were all located near large metropolitan cities like Detroit and Philadelphia, and were comprised only of blacks. If law enforcement’s violent reaction to the Black Panthers of the 1960s is any example, I seriously doubt if black militia units training with assault weapons, distributing recipes for building bomb, and preaching hatred for the government would be tolerated.90

Any analysis of the constitutionality of the militia movement entails two questions: i) the right to bear arms and ii) the right to form private militias. While the constitutional right to bear arms is unclear and subject to debate, the Constitution expressly prohibits forming private militias. A militia may consist of the citizenry at large, just as the patriot movement claims. It fails to note, however, that only Congress can call up a militia, which, in turn, remains subject to government regulation:

Private citizens cannot simply band together, saying “Okay, we’re a militia. We’re here to protect our rights against what we believe is a tyrannical federal government.” The militias of today’s patriot movement are functioning outside constitutional boundaries. They are unconstitutional militias. The Constitution stipulates, “Congress shall have the power…To provide for calling forth the militia…To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the militia…reserving to the states respectively, the appointment of officers, and the authority of training the militia.91

Alarmed by the World Trade Center bombing of 1993, the Clinton administration tried to pass the Omnibus Counter-Terrorism Act of 1995. It intended this legislation to allow the FBI more leeway to collect information and to conduct surveillance without prior court authorization. The act did not pass. Appearing before the Senate, Morris Dees advised lawmakers simply to enforce existing laws; the FBI did not need such sweeping powers. Most important, Dees reminded his audience, although they should never accept misconduct by federal law enforcement agencies, they should never take effective law enforcement for granted. It forgets that even before Ruby Ridge the government had peacefully resolved dozens of standoffs. Since then, it acknowledged its mistakes and has taken steps to insure that they will not happen again.

Tea Party protest at the National Mall on September 12, 2009. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0

Afterword

The Clinton Administration’s decision to limit deadly force significantly helped defuse the militia movement in the short term. The long-range impetus behind the militias waned for other reasons as well. The first, and most obvious, is that overturning the Federal government was never an achievable goal from the outset. However much ideological heat can be produced by stoking such fantasies could never drive a full-blown, right-wing revolution. Second, the logic of globalization, once so tempting for extremists to condemn as a conspiracy, has inexorably come to be accepted as part of twenty-first century social reality. Nonetheless, the extremist right continues to exert a disproportionately large ideological influence both domestically and internationally, though no longer in the form of an underground movement. The Tea Party represents the most recent expression of its disaffection, the roots of which can be traced back to the ongoing decimation of the middle class and the economic and social dislocation wrought be global capitalism. The progressive left has responded to these conditions as well, most notably through the Occupy Movement, which re-asserts the principle of communal public space and property against the logic of ongoing privatization. It is notable that how wealth is allocated is what fundamentally moves the populist right and left. Domestically, an ever-smaller elite lays claim to ever-more profits. Internationally, the distribution capital is beginning to include Third World economies rising out of the conditions of neo-colonialism. These are the underlying conditions of the Great Recession of the 2000s, which has so dramatically reduced the size and political clout of the middle class. The mandate, then, for the Tea Party has become to transform government, not overthrow it. It casts the proposed transformation as returning to the values of the founding fathers, even when such proposals blatantly contradict fundamental Constitutional principles. Embedded in the idea of such a return is the assumption that this will lead to a restoration of a once vibrant middle class. For example, Republican presidential candidate Rick Santorum’s recent assessment of John F. Kennedy’s 1960 speech to Baptist ministers in Houston, a speech that reaffirmed Constitutional separation of church and state is one such “return.” Santorum said the Kennedy’s speech made him want to “throw up.” What is perhaps most alarming in this is, apart from its vehemence, that it signals a perceived feasibility of merging church and state. For the immediate future it seems that the battle over such issues will be waged by debate within the ranks of the Republican Party – and not with weapons from remote and isolated survivalist compounds.

“Too Young to be a Hippy, Too Old to be a Punk (Discussion with Mike Kelley),” Be Magazin, Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, vol. 1, no. 1, 1994, 119–123.

James Wickstrom, The American Farmer: 20th Century Slave (1978) quoted in Richard Abanes, “Oh, What a Tangled Web,” America’s Militias: Rebellion, Racism, Religion (Downers Grove: Illinois: Intervarsity Press, 1996), 171. (Hereafter abbreviated AM.)

Carol Moore, “The BATF’s Ruthless Raid Plan,” The Davidian Massacre: Disturbing Questions About Waco Which Must Be Answered (Franklin, Tennessee and Springfield, Virginia: Legacy Communications and the Gun Owners Foundation, 1995), 99. (Hereafter abbreviated DM.) Moore further points out that the Posse Comitatus Act has been recently amended to sanction non-reimbursable US. military and National Guard support of civilian police in counter-drug operations.

James Coates, “Posse Comitatus,” Armed and Dangerous: The Rise of the Survivalist Right (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988), 105. (Hereafter abbreviated AD.)

Lyman Tower Sargent, “Posse Comitatus,” Extremism in America: A Reader (New York: New York University Press, 1995), 343-44.

Ibid, 343.

Morris Dees with James Corcoran, Gathering Storm” American’s Militia Threat (New York: Harper Collins, 1996), 10. (Hereafter abbreviated GS)

Catherine McNicol Stock, “The Politics of Producerism,” Rural Radicals: righteous rage in the American grain (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996), 18.

As a southerner, Jefferson naturally opposed the Federalists (Hamilton, Madison et al.) who, playing upon anti-Catholic sentiments, in turn disparaged his close ties with France. Jefferson, however, viewed immigration as a threat to American democracy.

Stock, “The Politics of Producerism,” 15-86.

Dees and Corcoran, GS, 11.

Coates, “The Politics of Hatred,” AD,197.

Coates, “Posse Comitatus,” AD, 111.

Ibid, 118.

Ibid, 112-13.

Ibid, 112-15.

Ibid, 116.

Abanes, “Misinformation Specialists,” AM, 118.

James Ridgeway, “Posse Country,” Blood in the Face: The Ku Klux Klan, Aryan Nations, Nazi Skinheads and the Rise of a New White Culture (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1995), 138-42. (Hereafter abbreviated BlF)

Coates, “Posse Comitatus,” AD 104-09.

Coates, “Posse Comitatus” and “The Compound Dwellers,” AD, 120-6.

Coates, “The Compound Dwellers,” AD, 121;132.

William L. Pierce, “The Lesson of Desert Storm,” Extremism in America, 187

Coates, “The Order,” AD, 48.

Lyle Stuart, “Introduction by the Publisher,” William Pierce (as Andrew McDonald) The Turner Diaries: A Novel (New York: Barricade Books, 1996) unpaginated.

Kevin Flynn and Gary Gerhardt, “Establishing the White American Bastion,” The Silent Brotherhood: The Chilling Inside Story of America’s Violent, Anti-Government, Militia Movement (New York: Signet, 1990), 105-06. (Subsequent chapter references are followed by the abbreviation SB. )

David Bennett, “Reshaping of the New Right, Rise of the Militia Movement,” The Party of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the MilitiaMovement, (New York: Vintage, 1995), 419. (Hereafter abbreviated PF.)

Pierce (as MacDonald) The Turner Diaries, 43.

Ibid, 45.

Ibid, 63.

William L Pierce, “A Program for Survival,” Extremism in America, 176-182.

Flynn and Gerhardt, “Enter the Zionist Occupation Government,” SB, 174.

Mormons believe that women’s sacred calling is to provide physical bodies for God’s spiritual children and that the second coming of Christ is near. In preparation for the millennium, like the survivalists, they stockpile food and other provisions.

Flynn and Gerhardt, “Robbie, the All-American Boy,” SB, 27-57.

Ibid, “Establishing the White American Bastion,” SB,105-127.

Ibid, “The Turn to Crime,” SB, 128-167.

Ibid, “Enter the Zionist Occupation Government,” SB, 203-208.

Dees had founded the Southern Poverty Center’s Klanwatch Project. Through Klanwatch, he effectively used the criminal justice system to battling racism. In 1981 he obtained a court order to stop Louis Beam’s Texas Emergency Reserve from harassing Vietnamese immigrant fishermen in Galveston Bay. In 1984 he sued Glen Miller’s Carolina Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, which led to the dissolution of that group. Miller, in the end, turned state’s evidence. In 1986 he obtained a $7 million judgment against the United Klans of America for lynching a black college student in Mobile, Alabama. This put the group out of business. In 1987, he bankrupted Georgia’s Invisible Empire with a $12.5 million court judgment. In 1989 he won a class action lawsuit against Tom Metzger’s White Aryan Resistance group for their part in the beating death of an Ethiopian immigrant in Portland, Oregon. This, too, bankrupted the organization. See Dees and Corcoran, “The Seditionist,” GS, 37-41 and “Recipe for Disaster,” GS, 98-103. Celebrity TV producer, Norman Lear, is best known for his character Archie Bunker, who epitomized bigotry as ignorance. Lear also founded a liberal lobby group with a conservative-sounding name: the American Family Foundation.

Flynn and Gerhardt, “Alan Berg: the Man You Love to Hate,” SB, 233-250.

Ibid,“Brink’s and the $3,800,000 War Chest,” SB, 255.

Ibid,” 271-290; “Survivalism: the Man Who Ate the Dog,” SB, 291-6.

Ibid, 349.

Ibid,“Judas Arrives on American Airlines,” SB, 379.

Ibid, “Survivalism: the Man Who Ate the Dog,” SB, 348-9.

Ibid, 354-55

Ibid, “Blood, Soil and Honor,” SB, 407-449.

Ibid, “Blood, Soil and Honor,” SB, 407-449.

Ibid, “Epilogue: Blood Will Flow,” SB, 450-51.

Ibid, 469-70

Former Green Beret Frazier Glenn Miller is the onetime leader of the Confederate Knights and the White Patriot Party. He was present at the Greensboro slayings of communist anti-Klan demonstrators in 1979 and ran for governor of North Carolina in 1984. That same year, attorney Morris Dees succeeded in barring Miller from further paramilitary organizing through a North Carolina civil suit. This effectively brought an end to his Confederate Knights. Miller went underground and declared war on ZOG. After his May 1987 capture, he turned state’s evidence and received a reduced sentence of five years in prison. See Flynn and Gerhardt, “Enter the Zionist Occupation Government, SB, 203-3 and “Epilogue: Blood Will Flow,” SB, 467. The minister James Ellison began the CSA as the Zarephath-Horeb Church near Bull Shoals, Arkansas. During the 1970s, Ellison took on a survivalist orientation and embraced Christian Identity theology. He set up a survivalist training center that included an obstacle course and Silhouette City, an urban mockup for street warfare. Randall Rader, later a key member of the Order, had been Ellison’s “defense minister.” By the early 1980s Ellison grew more extreme and more erratic. He declared himself to be “King James of the Ozarks” (tracing his lineage back to King David) and proclaimed that theft (from non-Identity people) and polygamy were sanctioned by the Lord. This, coupled with extreme poverty within the CSA compound, led to a general exodus by 1983. Order members Richard Scutari, Ardie McBreaty and Andy Barnhill also had CSA connections. See Flynn and Gerhardt, “Survivalism: the Man Who Ate the Dog,” SB, 304-308. The FBI laid siege to the CSA compound in April 1985 and Ellison was convicted of racketeering that same year. See Flynn and Gerhardt, “Epilogue: Blood Will Flow,” SB, 464.

US federal law prohibits the sale of shotguns with barrels less than eighteen inches long, except where special permits have been granted.

Alan Bock, “The Weavers’ Road to Ruby Ridge,” Ambush at Ruby Ridge (Irvine: Dickens Press, 1995), 52-3. Subsequent chapter references followed by the abbreviation ARR.

Ibid, 55.

Bock, “August 21-22, 1992: The Siege,” ARR, 7-9.

Ibid, 12-13.

Ibid, 20-21.

Ibid, “The Standoff,” ARR, 101-10.

Ibid,, “The Aftermath,” ARR, 240.

Larry Pratt is the executive director of both Gun Owners of America and the Committee to Protect the Family Foundation (the anti-abortion group which raised funds to protect Randall Terry). He is also founder of English First, a lobby opposed to bilingual education. Dees and Corcoran, “Rocky Mountain Rendezvous,” GS, 54.

Ibid, 53.

Ibid.

Ibid, 69.

Bock, “The Lawyers Close, The Jury Decides,” ARR, 227.

Ibid, “Update and Postscript,” ARR, 308.

Abanes, “The Saga of Ruby Ridge,” 49.

Moore, “Why the BATF and the FBI Massacred the Branch Davidians,” DM, 1-4.

Ibid, 14-15.

Ibid, 14-21.

Ibid, 19-21.

Ibid, 39-40

Bennett, “Reshaping of the New Right, Rise of the Militia Movement,” PF, 449.

Dees and Corcoran, “Bonds of Trust,” GS, 197.

Abanes, “The Saga of Ruby Ridge,” AM, 48.

Bennett, “Reshaping of the New Right, Rise of the Militia Movement,” PF, 457-59.

Ridgeway, “Introduction to the 1995 Edition,” BlF, 20.