→ Continued from “Between Objective Engagement and Engaged Cinema: Jean-Luc Godard’s ‘Militant Filmmaking’ (1967-1974), Part I” in issue 34.

If the films Godard made with the Dziga Vertov Group (DVG) show the historical, political, and sociological actuality, in Here and Elsewhere Godard and Miéville carve out a discursive position from which to retrospectively analyze May ’68 in France. They do this in 1974, concurrent with the Palestinian revolution.1 DVG filmed some of the material for Here and Elsewhere in Palestinian training and refugee camps in 1970. The material was edited after the dissolution of the DVG, under the auspices of Sonimage, the production company Godard founded with Anne-Marie Miéville in 1974. Here and Elsewhere is usually interpreted as advancing a revisionist discourse that critiques DVG’s “militant excesses,” claiming self-repentance for erroneous engagement in the face of the Black September massacres of 1970 and the wave of terrorism that followed, events that allegedly made Godard and Gorin realize the limitations of their previous engagement and compelled them to take a “turn” in their work.2 However, Here and Elsewhere does not differ drastically from other DVG films: it articulates an avant-garde point of view (here: the third-worldist or the militant abroad), uncovers the contradictions inherent to the situation it analyzes, and proceeds to self-critique. The difference is that instead of reflecting the political actuality, the film examines May ’68 and its practical and theoretical consequences. Godard and Miéville analyze, from the point of view of 1974, the contemporary legacy of May ’68 in Paris and Palestine. In the voiceover Godard declares:

We did what many others were doing. We made images and we turned the volume up too high. With any image: Vietnam. Always the same sound, always too loud, Prague, Montevideo, May ’68 in France, Italy, Chinese Cultural Revolution, strikes in Poland, torture in Spain, Ireland, Portugal, Chile, Palestine, the sound so loud that it ended up drowning out the voice that it wanted to get out of the image.3

Here Godard and Miéville address the predicament of May ’68, framing the question “Who speaks, for whom, and how?” as a failure: the putative speaker’s position is problematized because the supposedly self-critical intellectuals had spoken out too loud, drowning out the voice inside the images. Godard’s statement can be compared to Jean-Pierre Le Goff’s assessment of the failure of Maoism. Le Goff argues that the logic animating Maoists’ denunciation of power was a practical “settling of accounts,” denouncing oppression, exploitation, and racism by creating sensational media events. On this account, the Maoists failed due to an excess of dissent.4 Similarly, the voiceover in Here and Elsewhere claims that in spite of their self-criticism, the Maoists failed because their vociferous ideology drowned out the voice seeking expression through the filmed images. The intellectual’s failure to engage with revolutionaries abroad is rendered analogous to the impending breakdown of activist practice at home. In the quote cited above, “sound” should be understood as militant ideology, and the image inside the sound as art. Art had been drowned out by politics. When Godard and Miéville say that “people always speak about the image and forget about the sound,” they imply that the ideology that informed the discourse of political art-making overpowered the image. Images were thus spoken and not seen, obliterating the fact that sound had taken power over and defined them.

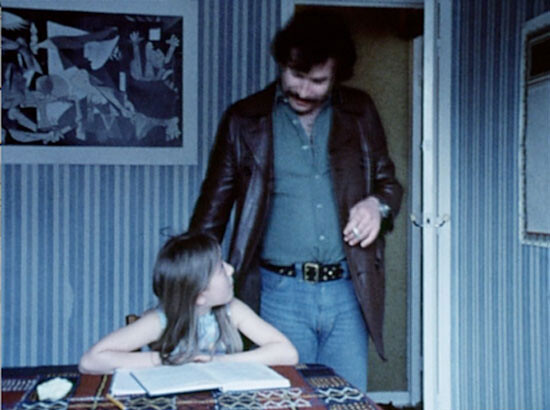

There is a scene in Here and Elsewhere that directly addresses matters of representativity. It takes place in the home of a working-class family, in a room where a young girl does her homework below a reproduction of Guernica that hangs from the wall. Off screen we hear her mother ask her father, “Did you find a job?” “No, I arrived too late,” he answers. The father goes into the room to greet the girl, who asks him, “Can you explain to me dad? I don’t understand.” He answers while walking out: “No, I don’t have time, we’ll see later.” The scene ends with the girl’s sigh of frustration. Guernica is the icon par excellence of intellectual militant struggles. Condemned by Sartre (in What is Literature? [1947]) and championed by Adorno (in Commitment [1962]), the image’s status as both an icon for militant struggles and a kitsch object, unlikely to be hanging in a working-class home, renders its presence in this scene ambiguous.5 Here Godard and Miéville allegorize the putting-out-of-work of political representation, aligning it with the crisis of patriarchy. The father can neither work nor help, like the union delegate or the intellectual. Explaining and helping to understand, which are tasks for intellectuals, militants, and fathers, are deferred or put out of work. In addition, Godard and Miéville amalgamate patriarchal responsibility and the revolutionary’s responsibility to mobilize at home (as opposed to going abroad). Instead of answering the call, revolutionary action gets postponed indefinitely: “I don’t have time, we’ll see later.” They critique through self-critique (which is the only means of problematization at this point) the intellectuals who went abroad and brought back materials to speak about the struggles of others without looking at what was happening at home, as Godard and Miéville lament having themselves done in the Middle East. The citation of Guernica and the (self-) indictment of “having spoken too loud” summon silence: Godard and Miéville call for silencing leftist ideology in the face of the failure of the Palestinian revolution, which embodies the failure of all revolutions. They are speechless.

When Godard declares in the voiceover that “we turned the volume up too high,” he is positioning himself in relation to Sartre’s concept of commitment. As we saw in Part I of this essay, Godard criticized Sartre for being unable to bridge his double position as writer and as intellectual. Godard himself sought to bridge this gap between art production and engaged activism in his practice of “militant filmmaking.” By citing Guernica and stating that “we turned the volume up too high,” Godard and Miéville contest Sartre’s skepticism about the power of images as a medium for the denunciation of injustice—a skepticism exemplified by Sartre’s dismissal of Guernica. For Sartre, insofar as images are mute, they are open receptacles of meaning and therefore invite ambiguous readings, as opposed to conveying a clear, unified message, like writing. Sartre claims that only literature can be successful as committed art because the writer guides his audience through a description, making them see the symbols of injustice and thereby provoking their indignation.6 Opposing Sartre, Godard and Miéville invoke Guernica’s quiet, visual scream, making a plea in favor of a flight from the prison of language, from logocracy.7

The fact that Guernica is not a speech act is perhaps the reason why it became the epitome of an autonomous yet committed work of art. While it remains separate from the public sphere (the domain of opinion and speech), it lets the German culpability surface, and, at the same time, it does not have as its end Picasso’s declaration of indignation.8 While we can, with Sartre, doubt whether Guernica converted anyone to the Spanish cause, this painting, like much of Godard’s work (a later example is his 1982 film Passion), posits a reflexive and analogical relationship between aesthetics and politics, as opposed to a transitive link. Transitivity is the effect of an action on an object, or the application of something to an object: here the application of politics to art, or vice versa. By contrast, an analogical relationship between art and politics implies a linking via aesthetics and ethics: if aesthetics is to ethics what art is to politics, it means that each term necessarily acts individually. A reflexive or analogical link between aesthetics and politics implies a relationship that acknowledges the presence of the other: they are separate, but aware of each other. Such a link presupposes film’s autonomy as relying on its having an end, which is different from being an end, or being instrumental to a cause: art appeals to viewers, calling for judgment or consideration.9

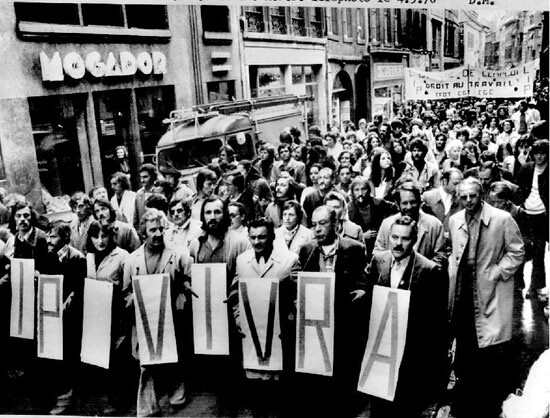

As we have seen, Maoists, breaking from the model of the Leninist vanguard intellectual, labored in factories alongside workers, all the while imbued with a Christian sacrificial rhetoric that claimed to serve the people, rejecting what they considered the exteriority of discourse in favor of the interiority of practice, and believing in the workers’ creative potential. Maoist struggles, however, were rendered obsolete by the self-managerial breakthrough at LIP, a watch factory in Besançon. In a 1973 interview with Maoists Philippe Gavin and Pierre Victor (the latter was Bernard-Henri Lévy’s pseudonym), Sartre discusses the LIP strike at length in relation to how it evinced the limits of Maoist revolutionary practice. Posing again the question “Who speaks?,” but now in humanist terms, Sartre, Gavin, and Victor sketch out the figure of the “New Political Man,” a synthesis of Maoist activist, intellectual, and politician. The New Political Man’s tools would be critical awareness, persuasion, and a renunciation of the superstructure. He would disseminate information in the public domain while remaining aware of the danger of becoming a “mediatic vedette.”10 A parallel figure—or perhaps an extension of the New Political Man—was the journalist: an intellectual who injected pressing debates into the public domain. After the dissolution of the Proletarian Left in 1973, it became necessary for the Maoists to reconceptualize engaged practice in order to further the politics of direct democracy. They publicly rejected their earlier Maoist activism, a gesture that went hand in hand with their critique of anti-totalitarianism. A new project, supported by Sartre and Foucault, was the founding of the daily newspaper Libération in the spring of 1973. Maoists demonstrated that they were increasingly media-savvy by producing a number of spectacular symbolic events covered by the media—therein the genealogy of “tactical media.” Not surprisingly, they rearticulated the practice of revolutionary journalism in terms of a collective “public writer.”11 One of the key themes of the May ’68 utopia was a society completely transparent to itself; this transparency was supposed to be achieved by the direct exchange of free speech without mediation, a theme that was then realized in Libération’s redefinition of mediation. The newspaper sought to democratically let all sides in a given conflict speak. Serge July defined the mission of the newspaper as the struggle for information under the direct and public control of the population, continuing the Maoist task of helping people to “capture speech,” as in their slogan “Peuple prend la parole et garde-la.”12 Libération’s impulse to democratize and to subvert content, to restore the “transparency of the code” by giving control of the information process to the people, was an attempt to reverse the circuit of information by initiating debate, as well as an attempt to realize the classic position of the Left regarding the democratic potential of the mass media. Influenced by the mass media theories of Benjamin, Brecht, and Enzensberger, their argument was that capital had hijacked the means of communication to promote and realize ideology. In this account, the media is posited as intransitive because it produces non-communication. In other words, communication through the media is unilateral.13 Ideally, the democratic potential of the media could be realized by breaking through this intransitivity and revolutionizing the apparatus and its content.14

As discussed above, for Godard and Miéville the leftist voice incarnated in Maoist activism did not go far enough in its contestation of intellectuals’ vanguardist position as the producers of common sense for the proletariat. Thus, in Here and Elsewhere they posed the new problem of the propagation of leftist doxa by the becoming-information of leftist discourse. Miéville and Godard would agree with Baudrillard’s critique of a leftist utopian view of the media, which held that unlimited democratic exchange is possible through communication. Such a position overlooks the fact that in essence, the media is speech without response. Even if efforts are geared toward the problem of the idle, passive reader-consumer whose freedom is reduced (like the viewer of political films) to the acceptance or rejection of content, such efforts are fruitless. Mediatization entails the coding of information into “objective” messages which are transmitted from a distance and which, because of the very nature of the apparatus, never get feedback. As Baudrillard put it, with the media “speech is expiring.” Baudrillard compares the media to voting, referendums, and polls. For him, all three share the logic of providing a coded state of affairs with which we must either agree or disagree, without having any agency over the content.15 Godard and Miéville sought to break away from the dichotomies of producer/consumer, transmitter-broadcaster/receiver, addressing them as a matter of the transformation of knowledge and communication into information (or codes), as a problem of cinematic voice and address.

Here and Elsewhere is, therefore, a film about utterances and visibilities gliding into one another in relation to cinematic voice, speech, discourse, expression, and their becoming-information, challenging the dominant forms of the shared sensible. Throughout the film, we see a multitude of open, speaking mouths: those of politicians, militants, and average people. We hear an array of sounds, speeches, and discourses: revolutionary songs and the sounds of war and the voices of the fedayeen, all from different discursive sites. Pointing out the discrepancies and the heterogeneous quality of the relationships between visibilities and utterances, Godard emphasizes the act of seeing, giving primacy to vision over discourse and speech; montage becomes the site of enunciation, shifting the problem from representation to matters of visibility, the visible, and the imageable. As he puts it in the voiceover: “Any everyday image is part of a vague and complicated system where the world comes in and out at each instant.”16

Through montage Godard makes images appear (comparaître) before the viewer, “giving to see” (donner à voir) as opposed to rendering or making visible. Here and Elsewhere presents a mélange of images: those filmed by Godard and Gorin in the Middle East, images filmed in Sonimage’s studio in Grenoble, images from journals and newscasts, and appropriated “historical” images and cartoons. The images appear in different formats or dispositifs: in television monitors, in filmed photographs, in video collages, in film footage, in slides, and in newspapers. Thus, the film is an accumulative disjunction of regimes of visibilities and discursivities embedded in their diverse material supports and channels of circulation. The regimes of visibilities can be divided into categories (slogan-images and trademark-images), genres (documentary, photojournalistic, pedagogic, epic), series (revolutionary additions, libidinal politics), and media (televisual screen, photography, and cinema). Sounds and sound-images are brought together through montage using the word “and” as the glue. For Godard, having been influenced by Walter Benjamin and André Breton, the actualization of an image is only possible through the conjunction of two others: “Film is not one image after another, it is an image PLUS another image forming a third—the third being formed by the viewer at the moment of viewing the film.”17 In Here and Elsewhere the conjunction/disjunction of the French working-class family and the fedayeen (who have the history of all revolutions in common) creates a fissure in the signifying chain of association in the film. The interstice between the “states of affairs” of the two (socio-historical) figures allows resemblances to be ranked, and a difference of potential is established between the two, producing a third.18 Such difference of potential is lodged in the syncategoreme “and.” The “and” is literally in between images, it is the re-creation of the interstice, bringing together the socio-historical figures along with the film’s diverse materials of expression in a relation without a relationship. Godard differentiates images by de-chaining them from their commonsensical chains of signification and re-chaining (or recoding) them in such a way that their signifiers become heterogeneous. Such heterogeneity resists the formation of a visual discourse resonant with the commonsensical image of the Palestinian revolution found in photojournalistic and documentary images visible in the French mass media. Through appropriation and repetition, Godard produces a sort of mnemotechnics that allows us to memorize the images and thus link their signifiers in diverse contexts: the operations of disjunctive repetition and appropriation pull out what the signifiers lack or push out their excess. This assemblage of images and sound-images from diverse regimes of visibilities and discursivities, linked through the word “and,” creates additional images, providing a multiplicity of points of view. Such an assemblage destroys the identities of images, insofar as “and” substitutes and takes over the ontological attribution of those images: their “this is,” the eidos of images (their being-with, or Être-ET).19

Privileging the act of seeing that underscores the distinction between speech and discourse in Here and Elsewhere, Godard and Miéville speak in the first person in the voiceover, calling for an ethics of enunciation that accounts for the intransitivity of mass media and undermines the code of objectivity proper to the media.20 For Godard and Miéville, “objectivity” requires that images hide their own silence, a “silence that is deadly because it impedes the image from coming out alive.” They thus work with the imperative to ask of images: “Who speaks?” And for them, all images are always addressed to a third: “Une image c’est un regard sur un autre regard présenté à un troisième regard.”21 Thus, images must be understood as immanent to an interlocutionary act, especially documentary and photojournalistic images, which, obliterating the mechanism of mediation, put forth objectivity as a discursive regime in which either “no one speaks,” “it speaks,” or “someone said.” The ethico-political imperative becomes, therefore, to take enunciative responsibility, to speak images and acknowledge authorship over them, to make images speak and to restore the speech that has been taken away from them, accounting for the intentionality immanent to the act of speaking for and of others as an act of expression emphasizing direct address—absolutely foreign to confession or situated knowledge, in the manner of écriture.22 By means of direct address, the subject of speech in Here and Elsewhere is located at the juncture of diffusing, receiving, emitting, and resending images and reflecting upon them. Godard and Miéville thereby become immanent to the videographic apparatus, speaking from an inter-media discursive site constituted by video passing in between television, cinema, photography, and print media.

Godard’s war of position between 1967 and 1974 can be summarized as the production of contradictory images and sounds that call viewers to produce meaning with the films, as opposed to consuming meaning. We can name it a politics of address, a “the(rr)orising” pedagogy, or Brechtian didacticism. Godard’s collaborations with Gorin and Miéville create dissensus while calling for a radical way of hearing and seeing. In their work, the task of art is to separate and transform the continuum of image and sound meaning into a series of fragments, postcards, and lessons, outlining a tension between visuality and discourse. Evidently, for Sonimage the stakes in asking the question “Who speaks, for whom, and how?” had migrated from the realm of cinema into television and the communications media. This is due not only to the mediatization of intellectual mediation sketched out above, but most importantly, because of the ethical and political problems raised by the Palestinian footage in relation to militant engagement with Third World revolutionary movements and the pervasiveness of images of such movements in the media. For Godard and Miéville, it became pressing to articulate a regime of enunciation that would continue DVG’s critique of auteur theory in film, while addressing in a pedagogical manner the discursive regime of mediatic information and the problem of the expiration of speech.

For an analysis of Here and Elsewhere as it relates to the movement of Third Worldism and Godard’s engagement with Palestine, see Irmgard Emmelhainz, “From Third Worldism to Empire: Jean-Luc Godard and the Palestine Question,” Third Text 100 (September 2009), 100th Anniversary Special.

See Serge Daney, “Le thérrorisé (Pédagogie godardienne),” Cahiers du Cinéma nos. 262–263 (January 1976): 32–39; and Raymond Bellour, L’entre-images Photo. Cinéma. Vidéo. (Paris: La Différence, 1990).

“On a fait comme pas mal de gens. On a pris des images et on a mis le son trop fort. Avec n’importe quelle image: Vietnam. Toujours le même son, toujours trop fort, Prague, Montevideo, mai soixante-huit en France, Italie, révolution culturelle Chinoise, grèves en Pologne, torture en Espagne, Ireland, Portugal, Chili, Palestine, le son tellement fort qu’il a fini par noyer la voix qu’il a voulu faire sortir de l’image.” Ici et ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere), 55 min, Chicago: Facets Video, 1995. Emphasis mine.

Jean-Pierre Le Goff, Mai 68, L’Héritage impossible (Paris: La Découverte, 1998), 201.

Adorno’s Commitment was originally published in 1962 as both a radio address and a journal article. In 1968 a number of US protests against the war in Vietnam used Guernica as a peace symbol. A year earlier, some 400 artists and writers petitioned Picasso: “Please let the spirit of your painting be reasserted and its message once again felt, by withdrawing your painting from the United States for the duration of the war.” In 1974, Toni Shafrazi spray-painted the words “Kill Lies All” on Picasso’s iconic painting. See Picasso’s Guernica, ed. Ellen C. Oppler (New York and London: Syracuse University Press, 1988). The symbolic power of Guernica was further highlighted in January 2003 when a reproduction of the painting in the UN headquarters was covered during Colin Powell’s presentation of the case for invading Iraq to the Security Council. This blocked the production of images (by the press) of the Security Council with the reproduction in the background.

Jean-Paul Sartre, What is Literature?, trans. Bernard Frechtam (New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1965), 4. First published in France in 1947.

See Walter Benjamin, “The Author as Producer,” New Left Review vol. 1, no. 62 (July–August 1970) 84-85. For Jacques Derrida, Guernica’s denunciation of civilized barbarism occurs in a dead silence that allows one to hear the cry of moaning or accusation. This cry joins the screams of the children and the din of the bomber. See Derrida, “Racism’s Last Word,” Critical Inquiry 12 (Fall 1985), 290-301.

See Adorno, “Commitment,” in Notes to Literature, Volume Two, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Shierry Weber-Nicholsen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 76-94.

This is Adorno and Pierre Macherey’s position regarding the relationship between aesthetics and politics. For Macherey, art has an end insofar it presupposes a subjective pact between viewer and author based on general trust: the author’s word is to be believed, the receiver’s is an act of faith. Before the work appears, there is an abstract space presupposing the possibility of the reception of the author’s word. See Pierre Macherey, Pour une théorie de la production littéraire (Paris: François Maspero, 1966), 89-91. Thierry de Duve posits the problem of art as an end via Kant’s aesthetic judgment, arguing that “the notion of artists speaking on behalf of us is essential to art as art, and its legitimacy does not hinge on the artist’s purportedly universal mandate but rather on the artwork’s universal address.” (My emphasis) See Thierry de Duve, “Do Artists Speak on Behalf of All of Us?,” in Voici -100 d’art contemporain (Brussels: Museum of Fine Arts, 2001).

Jean-Paul Sartre et al., On a raison de se révolter (Paris: Gallimard, 1974), 288-340.

Kristin Ross, May ’68 and its Afterlives, (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2002), 114-116.

“People seize speech and keep it.”

See Jean Baudrillard, “Requiem for the Media” (1972), New Media Reader, ed. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2003), 280.

See Brecht’s “The Radio as an Apparatus for Communication” (1932); Walter Benjamin’s “The Author as Producer”; Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s “Constituents of the Theory of the Media,” in The Consciousness Industry (New York: Seabury Press, 1974), 95-128; and Baudrillard’s critique of this position in “Requiem for the Media,” ibid.

Baudrillard, ibid.

“N’importe quelle image quotidienne fait partie d’un système vague et compliqué, où le monde entier entre et sort à chaque instant.”

“Le cinéma ce n’est pas une image après l’autre, c’est une image plus une autre qui en forment une troisième, la troisieme étant du reste formée par le spectateur au moment où il voit le film.” Godard in “Propos Rompus,” Jean-Luc Godard par Jean-Luc Godard (Paris: L’Étoile et Cahiers du cinéma, 1985), 460.

See Gilles Deleuze, Cinema II: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2001), 180.

Gilles Deleuze, “Trois questions sur Six fois deux: A propos de Sur et sous la communication,” Cahiers du Cinéma 271 (November 1976).

Here I am taking after the linguist Oswald Ducrot who argues that the talking subject introduces sentences (in enunciation) that necessarily contain the responsibility of the utterer; in other words, in enunciation the speaker is committed to the semantic content. That is why for Ducrot, speech acts constitute expression. See Oswald Ducrot, Logique, structure, énonciation: Lecture sur le langage (Paris: Minuit, 1989); and Les mots du discours (Paris: Minuit, 1980).

From the voiceover in Here and Elsewhere.

According to Jacques Derrida, in the domain of écriture there is a movement in language at its origin, which conceals and erases itself in its own production. This means that in écriture the signified always already functions as a signifier. With écriture, Derrida undermines the Aristotelian idea of theLogos as the mediation of mental experience along with the movement of “exteriorization” of the mental experience as a sign of presence. The function ofécriture is, therefore, to conceptualize the dissolution of the signifier in the voice by splitting signified and voice: in écriture, the subject of a text is coherent with the text, becoming the object of écriture, displacing the signified from the author. See Derrida’s Of Grammatology, corrected edition, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997).