It is hard to distinguish individuals in a crowd. Citizens of the Gulf states appear to the visitor as crowds, with their identities as individuals momentarily suspended. Such a crowd is slightly different from the kind described by Elias Canetti. This is a crowd perceived as such by a visitor conscious of his individuality against the multitude. The crowd exerts no control over this visitor, nor does it repress his personality. Rather, this visitor exerts a form of authority—engaging in an exchange of power with the crowd. For him, the citizen is imprisoned within the crowd, incapable of assuming the authority of an individual.

Visual encounters between citizens and visitors take place primarily in neutral public spaces where the visitor’s behavior is less restricted. By entering a hotel lobby, for instance, the citizen declines the possibility of establishing authority and becomes helpless. The citizen can be neither a soldier nor a noble person, but is also incapable of becoming a barbarian, an indistinguishable part of a great multitude—a grain of sand along the seashore, as Ernest Renan described barbarians. Barbarians for Renan are numberless; they tirelessly procreate despite the numerous deaths they suffer. Furthermore, their deaths complement their procreation, which is why they appear countless to Renan and other nineteenth-century European racialist thinkers

But this is not how the visitor perceives the citizen of the United Arab Emirates; this citizen is part of an absent crowd. In public he appears isolated and weak—lonesome in a colonized land. The citizen appears to be performing the role of an individual, summoning a display of mannerisms in the hope of finding a place for the national costume in public space. This “uniform” is a national disposition, or perhaps an assertion of loyalty to an identity in spite of knowing it is restrictive. It is a form of reconciliation between a constructed identity and a possible connection to a formalistic modernity. The modernity experienced in hotels is superficial, and this citizen seems to imply that his costume is but one extra mask in a stage full of masks.

We can think of the national costume as a veil—not the veil that allows fundamentalists to retain their individuality, but a veil that elevates identity above intermingling. As a social necessity that is very costly to the individual, it marks a restrictive obsession with identity. It appears to instigate a challenge to visual identity, to provoke a deeper form of intimacy that transcends this outer veil. It suggests a form of intimacy requiring an effort in order to be earned. The costume then becomes a form of authority that allows people to see without being seen. By blending into the crowds, the citizen disappears from view, but can still observe the others wearing their masks in public.

Let’s take a closer look at this form of authority that the costume grants the citizen over the visitor. There is a legal aspect, but also a moral one that presupposes that the citizen always has the last word on any matter—and these mask a more complex condition.

In legal terms, the citizen can master geography through the rights of property ownership. But this is a fragile mastery that can instantly turn the geography into a desert. The citizen has the right to die. His entitlement to death and burial is geographic—he is free to mate and procreate, but always in the deep sand that the entire place is made of. Let’s propose this equation: the citizen is entitled to be buried in the sand, while the guest is entitled to live there. These are not equal entitlements, for it is the guest who turns the virginal geography into a semblance of a city. The citizen meanwhile shuns the ease of life in the city, leaving this life to the visitors. But it is a life lived transiently, as if for one night. The masters of geography live there forever.

Morally speaking, it appears that the citizen’s loyalty to his costume and identity grants him the authority to shun different ways of living. Through his tolerance and compassion, he allows others to live without infringing upon the lightness of their existence with his decisive authority. But there remains a dichotomy that forces a choice between a more noble and elevated sense of entitlement and an easy life, a lightness of being that favors a loss of roots extending deep into the sand.

And while the citizen has the uncontested right to rule decisively on any matter, this is a right that is seldom practiced. Exercising this authority confronts the citizen with death, and so it is an authority that is predicated by its infrequent use.

Petrol in this land flows pure as gold. Oil is the indisputable pillar on which this country has transformed itself. This precious substance played a substantial role in three generations of social transformation. The generation of the 1950s and early 60s established the basis for the country’s relationship with the outside world, with its leaders striving to connect their societies to modernity without betraying their heritage and traditions. The people of that generation traveled around the world, experiencing it as individuals. There were giant leaps between these three generations that would have never been possible without the proceeds of oil trading, and the third generation discovered suddenly that the modern world could not justify its presumptuousness. They immersed themselves in knowledge and exploration, accelerating the pace of their development in an astounding manner. The people of this land can always surprise you—they conceal themselves and hide their charms from transient eyes. But real interaction with them remains perplexing. Within three generations, they went a long way towards establishing their identity and the basis of their relationship to the Other, but later experienced challenges to this identity abroad and the dichotomies of being suspended between two civilizations. They encountered confrontations with the Other that made it necessary to summon arguments to prove the strength of their identity.

The oil boom allowed this country to develop at record speeds, overcoming challenges that in other countries led to disaster. But oil’s curse is no secret. These rapid achievements, massive public works, and grandiose projects only widened the generational gap, and dialogue between the different generations has only been further suppressed. The outside observer does not detect this tension, but to those concerned these differences appear to be insurmountable. Identity appears to be suspended by an invisible wire, which wants to disappear completely but still remain intact. Everything here is judged through touch and experience—the eye is ineffectual because it only sees the surface.

Thus, the people of this land try to conceal the cracks that could be noticed by the visitor. Many visitors are shocked by the presence of poor neighborhoods in some cities. The Gulf states are under scrutiny, and poverty there is a concern for others. News of poverty and unemployment in Saudi Arabia are greeted with shock, for the country is expected to eradicate poverty.

The second generation of citizens in the UAE enjoyed positive relations with the West. However, this relationship demanded that they sever their links with their history. They inherited their image from their predecessors, but were required to deny its roots in order to attain knowledge and satisfy their curiosities in the West. Sharing knowledge and communicating with the Other are difficult tasks, and they dictate a single driving desire: a curiosity that voids the self and renders it ready to accept anything that promises fulfillment.

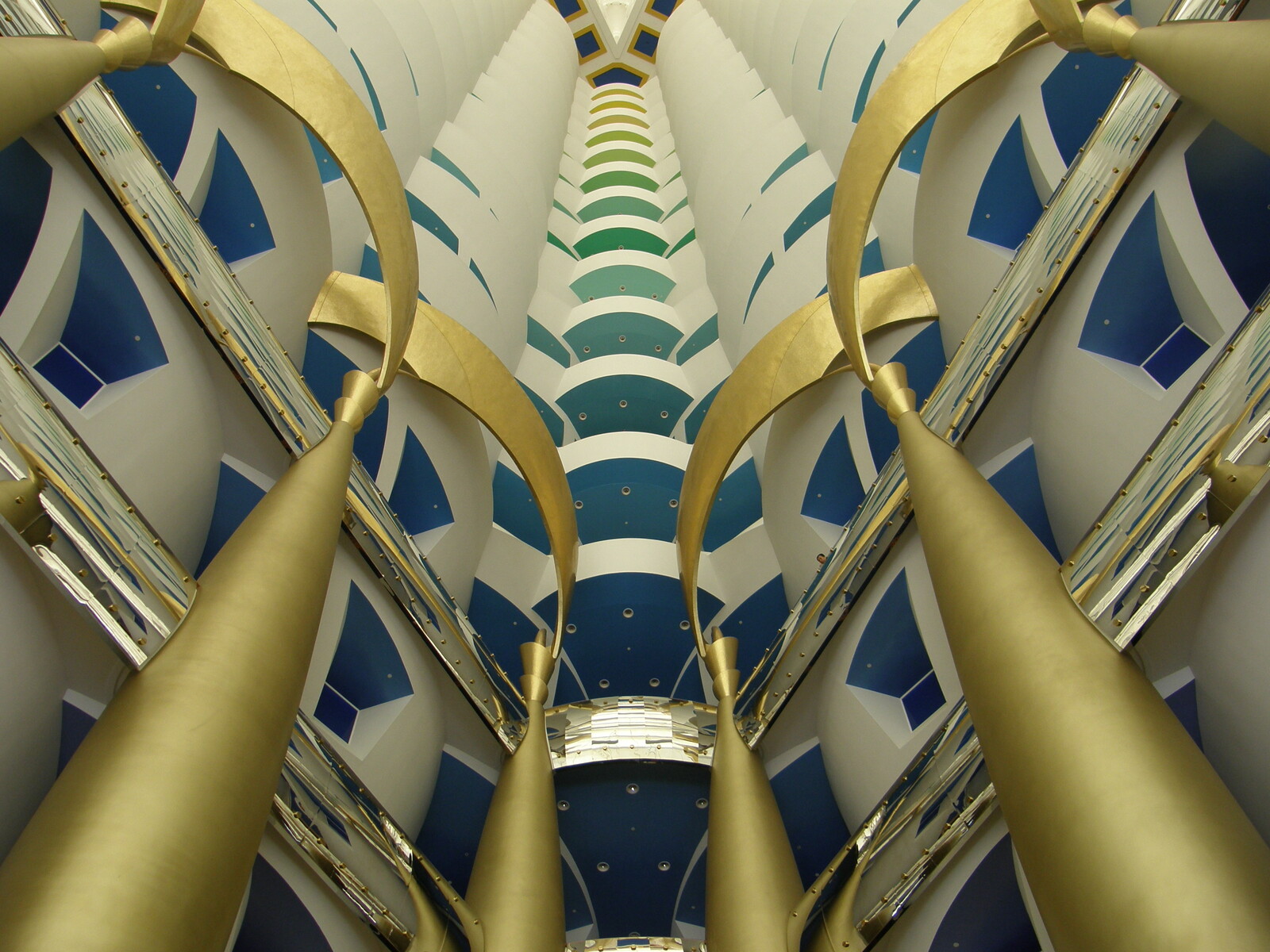

For these reasons, the passion for monuments in the Gulf remains a curiosity, because the monuments are made to conceal an identity. There is an ongoing spectacle of modern music, high-end retail, fashion designers, expensive hotels, luxury cars, all of which comprise a compensatory escape act—a resistance to the feeling of confronting death, but by way of a frantic level of activity, that is, through exhaustion. The meeting of exhaustion and vitality in one body makes death simultaneously tangible and distant. They allow one to invite death so as to escape its clutches.

Encountering the Other, and attempting to interrogate and recreate the Other’s experience, requires a form of betrayal. Immersion in another’s experience is a self-deprecating exercise. There is an instantaneous confusion: a strong identity and known lineage must be renounced. This renounced self becomes proof of the Other’s loyalty to his own identity, as well as of the possibility of its denial.

Countries allow us to belong when they have the resources at their disposal to secure a stable future. Oil then becomes very important as the medium through which we and the Others collude to anticipate our future. In international trade, oil also promises a stable future, but it is a leased future, manufactured through a chain of intermediaries. It is a future built by mercenaries, and it is through them that this country is allowed to be distinctive in its modernity.

It is a form of betrayal to seek to attract such a high volume of skilled labor, for the architects and designers who unleash their creativity onto the desert develop a sense of custodianship towards the cities they build. To employ engineers, educators, and doctors as the makers of the future, is to transform them into artists—and they will defend their products like valuable works of art. In the meantime, the citizen becomes a viewer, watching his or her country on a screen rather than living in it. Rather than emigrating abroad, the citizens immigrate inwards, as if into a secret. As they do this, they cease to be visible, yet they can always see the masterpiece their land has become. They watch it from the inside out, as if they lived in the belly of a statue.

Category

Subject

Translated from the Arabic by Karl Sharro.