It is often argued that between 1967 and 1974 Godard operated under a misguided assessment of the effervescence of the social and political situation and produced the equivalent of “terrorism” in filmmaking. He did this, as the argument goes, by both subverting the formal operations of narrative film and by being biased toward an ideological political engagement.1 Here, I explore the idea that Godard’s films of this period are more than partisan political statements or anti-narrative formal experimentations. The filmmaker’s response to the intense political climate that reigned during what he would retrospectively call his “leftist trip” years was based on a filmic-theoretical praxis in a Marxist-Leninist vein. Through this praxis, Godard explored the role of art and artists and their relationship to empirical reality. He examined these in three arenas: politics, aesthetics, and semiotics. His work between 1967 and 1974 includes the production of collective work with the Dziga Vertov Group (DVG) until its dissolution in 1972, and culminates in his collaboration with Anne-Marie Miéville under the framework of Sonimage, a new production company founded in 1973 as a project of “journalism of the audiovisual.”

Godard’s leftist trip period can be bracketed by two references he made to other politically engaged artists. In Camera Eye, his contribution to the collectively-made film Loin du Vietnam of 1967, Godard refers to André Breton. Then in Ici et ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere), a film Godard made with Anne-Marie Miéville in 1970–74, he cites Picasso’s Guernica (1937). These references help explicate Godard’s leftist trip years. In the former, Godard (mis)attributes to Breton a position aligned with the French Communist Party and their instrumentalization of art in the name of a political cause—what we will call “objective denunciation.” In the latter, by citing Guernica Godard enters into a dialogue with Jean-Paul Sartre and his theories on political engagement and aesthetic autonomy, especially his debate with Adorno about the effectiveness of images versus words in transmitting political messages. Oscillating between these two positions, Godard carved out his own form of objective denunciation in opposition to Sartre’s schizophrenic split between two activities that he considered to be incommensurable: “artistic enunciation” and “active political engagement.” Godard synthesized these activities, exploring and embracing the contradictions between the roles of “filmmaker” and “militant.” We must bear in mind, however, that Godard’s revolutionary constellation cannot be reduced to these literary references. Indeed, in La Chinoise (1966) Godard established the genealogy of his politicized aesthetics—one that departed from traditional European intellectual history—by classifying literary authors, philosophers, and artists as either “reactionary” or “revolutionary.” In general, between 1967 and 1974 Godard developed a revolutionary imaginary in which Dziga Vertov and Bertolt Brecht were pioneers, Breton was a deviation, Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle was a shared paradigm, Sartre was his bête noire, and philosophers such as Michel Foucault, Julia Kristeva, and Gilles Deleuze were his compagnons de route (fellow travelers).

Figures like Breton and Sartre are inseparable from the history and tradition of the French avant-garde, which I consider here in light of the relationship between French intellectuals and the French Communist Party (PCF). Modeled after Lenin’s vanguard party, the PCF bestowed a pivotal role on intellectuals between the end of World War II and 1965: the production and transmission of political knowledge to the proletariat. As described in What Is To Be Done?, Lenin’s Party functioned as the vanguard of the proletariat, a highly centralized body organized around a core of experienced intellectuals designated as “professional revolutionaries” who were charged with leading the social democratic revolution.2 This ideological avant-garde operated in the realm of opinion and leftist common sense, putting art in the service of political causes and taking for granted the artist’s position as the porte parole of humanity. Such an avant-garde posits a transitive relationship between art and politics—that is, a causal relationship between the two, even the instrumentalization of art in the name of leftist political ideology.

Committed French avant-garde artists, intellectuals, and writers were obliged to take a position regarding the PCF and its dogmatic socialist-realist aesthetic.3 For example, Althusser and Aragon were members of the party, Breton was a dissident, and Sartre was a distant “fellow traveler” and the “party’s consciousness.” Breton claimed to be a communist but distinguished his own artistic practice from the PCF’s socialist realism; he lamented the party’s “bad taste” and averred that the “leftist political milieus do not know how to appreciate art outside of art made with consecrated and expired forms.”4 The heyday of the PCF as a point of reference for intellectuals coincided with the highpoint of Structuralism, when political discourse and the ethics of the intellectual were shaped by Marxism, psychoanalysis, and linguistics. At that time, “the signifier” (the author, the phallus, the father) was treated with the greatest respect, as were intellectuals, who were regarded as public figures speaking truths.5 In the Sixties, however, the signifier, the phallus, and the father were contested as figures of authority and truth. Likewise, intellectuals and their status as the consciousness of the party and society were challenged. As Frederic Jameson has argued, this was an unprecedented situation in which it became possible for radical intellectuals to imagine revolutionary work outside and independent of the PCF.6

Enter Maoism. To subscribe to Maoism was a way of taking a position against the Communist Party in accord with the Sino-Soviet split and to disconnect from the “dark” outcome of the Cultural Revolution. In line with the attempt to break away from the model of the vanguardist intellectual, the Maoists “established” themselves in factories; they worked alongside the workers and rejected the exteriority of discourse in favor of the interiority of practice, believing in the creative potential of the proletariat. By rejecting theory in favor of practice and giving preference to direct intervention (without mediation), Maoism embraced the mythical junction of students and workers and declared war against the despotic regime of the signifier, the figure from above who speaks truths. Around May ’68, rejecting the idea that “knowledge is power,” Maoists launched an attack on vanguardist politics by posing the following questions: Who speaks and acts, from where, for whom, and how? Specifically, these interrogations were addressed to union delegates, intellectuals, professors, writers, and artists, as Maoists questioned the representativity of engaged intellectuals and delegates. Maoists challenged their legitimacy as disinterested agents who could speak critically on behalf of the proletariat and lead the Revolution. Walter Benjamin’s critique of Lenin’s professional intellectual was influential in the French Sixties. For Benjamin, the problem with professional intellectuals is that when they attempt to integrate themselves into the proletariat, they ignore their own position in the process of production. Benjamin calls this the trap of logocracy, a system that implies the ruling power of words.7 In order to avoid this trap, Maoists prioritized practice (working alongside workers) and denigrated discourse, focusing their energies on liberating the forms and instruments of production (to achieve self-management) and promoting self-representation.

In accord with Maoist theory and practice, the logic under which Godard’s work operated during this period was not that of the old ideological avant-garde but that of the war of position, a strategic rather than an ideological approach. Godard’s avant-garde was nominal insofar as it transformed proper names, cries, battles, and avant-garde positions into concepts and slogans. The filmmaker’s vanguard was further predicated upon a relationship to art of the past that differed from the traditional vanguardist negativity; instead of treating it as a tabula rasa, Godard reclaimed, contradicted, and disavowed the art of the past. His strategy, therefore, consisted of repeating, testing, and incorporating different historical and contemporary avant-garde strategies through the logic f Maoist double negativity or contradiction. Maoist contradiction is a kind of nondialectical, eternal struggle of opposites which starts from a principal contradiction to which other contradictions are subordinated. Maoist contradiction is thus a self-revolutionizing logic that, instead of reaching a higher order, advances from quantitative change to qualitative change through leaps forward. Godard’s gesture of simultaneously incorporating and rejecting politicized modernism reflected the epistemological change brought on by the post-structuralist separation of the signifier from the signified. This shift brought representation into crisis and was transfigured into the theoretical and practical ideologemes of the Left: instrumentality, realism, reflexivity, didacticism, and historiography.8 Taking into account the theoretical-practical problems of these ideologemes, Godard developed a series of contradictions relating to the new historical problems that brought traditional Marxism to its limits, such as the novelty of an emergent class of university-educated consumers and the relationship between art and the explosion of mass media and information—phenomena without historical precedents.

In Godard’s Camera Eye, we see an image of Godard standing behind his camera. This image is interspersed with images from life in Vietnam. In the voiceover, Godard says that these images of Vietnam are similar to those he would have filmed if the authorities had issued him a visa to visit Phnom Penh. He also states maliciously that in adopting his own engaged position of “the long revolutionary wait and of objective and declarative enunciation,” he takes after André Breton. It is malicious to attribute this attendiste position of the PCF to Breton because, as mentioned above, Breton distanced himself from the party. This position implies that the artist, while waiting for the revolution, speaks out ceaselessly for others, expressing his indignation in the name of just causes. Godard thus calls for the imperative of listening to and transmitting a scream of horror against injustice. Godard further states that he is aware that art cannot change the world but what he can do, as a filmmaker in France, is to articulate his rage and criticism as often as he can: that is why he mentioned the Vietnam War in every single one of his films until the war ended, from Vivre sa vie (1962) until Tout va bien (1972). This position is that of objective denunciation, which implies a transitive relationship between aesthetic and politics: art is put in the service of political critique, denying art’s autonomy from ethics and politics. In his manifesto Pour un art indépendant révolutionnaire (1938), Breton stated the following:

True art, which is not content to play variations on ready-made models but rather insists on expressing the inner needs of man and of mankind in its time—true art is unable not to be revolutionary, not to aspire to a complete and radical reconstruction of society. This it must do, were it only to deliver intellectual creation from the chains which bind it, and to allow all mankind to raise itself to those heights which only isolated geniuses have achieved in the past. We recognize that only the social revolution sweeps clean the path for a new culture.9

For Breton, “true art” or advanced art must be led by social revolution. Breton’s position implies a causal link between aesthetics and politics: if there is political freedom (through social revolution), then there will be aesthetic liberation. Further, true art is necessarily revolutionary. This means that any art that does not have political freedom as its basis and the emancipation of humanity as its purpose is not true art. A question thus arises: Does Godard, by adopting the same avant-garde position as Breton (his real position, not the misattributed one), likewise deny art any autonomy from politics? Such a position would imply a causal link between aesthetics and politics: if political freedom, then aesthetic liberation. By contrast, the position of objective denunciation entails that aesthetic activity be intrinsically linked to political action as the means to achieve or announce the emancipation of humanity. As we will see, Godard’s position is more complex, as it was not only in dialogue with the vanguardist tradition, but he also entered into dialogue with Jean-Paul Sartre.

Sartre believed that artists are not obliged to follow any mandate, yet they are called to speak critically in the name of the emancipation of humanity. In this sense, objective denunciation is similar to Sartre’s model of “collective objectivity,” which calls for the exercise of one’s freedom in order to act in the name of universal values. Sartre’s position, however, implies a schizophrenic split between the “writer function” and the “intellectual function.” In Sartre’s view, a writer inhabits a fundamental contradiction. On the one hand, the artist/writer is a creator and articulates his being-in-the world through language, producing partial yet universalizing non-knowledge. The writer is also capable of producing practical knowledge, and he does so not in his own work, but by operating in “lived reality” in the name of universal truth. What is at stake here for Sartre is the “utility” of works of art and the contradictory situation in which writers live: the non-knowledge that the writer produces (knowledge that is not scientific or objective—savoir as opposed to connaissance) mainly serves the class in power and has limited use for the masses, since artworks are shaped by class interests. That is why for Sartre the writer has two functions, the intellectual function and the writer function: the intellectual is not mandated by anyone and therefore, produces practical truths in the name of the universal.10 According to Sartre the two activities were unbridgeable. Godard explained his relationship to Sartre and his engaged position in an interview in 1972.

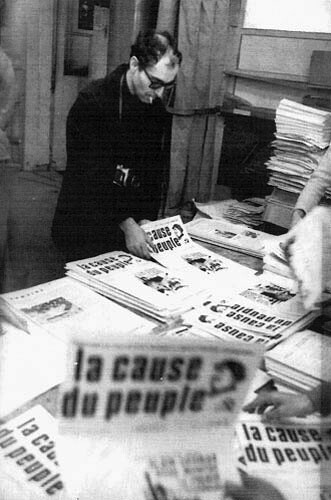

I participated with him [Sartre] in a few actions for [the journal] La cause du peuple.11 And after, I tried to establish a dialogue with him but it was impossible. I was trying to know what was the relationship between his texts about the Russell Tribunal or about the Houillères, which were amazing texts, and his older or recent studies about Flaubert and Mallarmé. He then tells you that there are two men in him. One who continues to write about Flaubert because he doesn’t know what else to do, and another one who has thrown himself with all his soul into the struggle, by going to address the workers at the Renault factory standing on top of a barrel. We don’t deny either position. We simply think that as an intellectual radicalizing himself, he should bridge both positions.12

Thus there is “Sartre-the-writer,” who spends ten hours a day writing about Flaubert, and “Sartre-the-intellectual,” who addresses workers from the top of a barrel.13 The intellectual speaks out while the writer works subjectively with language.14 Clearly, Sartre drew a distinction between the writer and the intellectual in order to avoid a transitive relationship between aesthetics and politics. For Sartre, objective denunciation must take place separately from the field of aesthetic production, in the domain of engaged activism. Literature (and art) is thus severed from a critical function. “Freedom” in the aesthetic and in the political domain is maintained not by a transitive link, but by a separation: art is autonomous non-knowledge that is subservient to the class in power, and therefore the artist/writer is an unhappy consciousness pushed to act politically in the empirical realm. Furthermore, for Sartre a work of art or literature does not have to be measured by its “effectiveness” in the realm of politics or ethics, since artworks should not be effective in the political realm. Taking Picasso’s Guernica as an example, he famously stated, “Does anyone think that it won over a single heart to the Spanish cause?”15 Further, Sartre’s intellectual function involves a “radical overcoming” (dépassement radical) of the bourgeois writer function in order to become a “transcendental consciousness” and to bring truth to institutions that lack it (Sartre was the Party’s consciousness) and to carry philosophy to the streets (he was the proletariat’s fellow traveler).16

Godard grappled with Sartre’s split between engaged activism and artistic enunciation in a text from 1970 published in Manifeste, Fatah’s17 journal in France: “In literature as in art, to fight on two fronts. The political front and the artistic front—that is the current stage, and we’ll have to learn to resolve the contradictions between these two fronts.”18Adopting Breton and Sartre’s opposing avant-garde positions and holding them in suspension allowed Godard to highlight the contradictions inherent in both models of the aesthetic-political avant-garde. This mirrored his own effort to problematize both the transitive relationship between politics and aesthetics implied by objective denunciation, and the separation between the artist and the activist implied by Sartre’s belief in the autonomy of art. As we have seen, Godard claimed that Sartre did not go far enough; in his view, Sartre should have attempted to reconcile the intellectual function with the writer function. Bridging Sartre’s split between active engagement and artistic enunciation, while also going beyond the practice of objective denunciation, Godard adopted the position of “militant filmmaker.” In this manner, Godard kept his filmmaking practice somehow separate from the “intellectual” function of active engagement, yet the two positions—militant and filmmaker—could be easily conjoined because in his Marxist-Leninist films, the relationship to the political is not clearly intransitive, as we shall see.

In his political sympathies, Godard gravitated towards the Proletarian Left Party (Gauche Prolétarienne, a Maoist party active from 1969-1973), collaborating in actions around their journal La Cause du peuple.19 Godard also wrote five articles for the Maoist journal J’accuse and helped create the newspaper Libération.20 When he founded the Dziga Vertov Group with Jean-Pierre Gorin in 1969, Godard reinvented his practice as a filmmaker. His purpose was to rethink the notion of authorship—specifically, the auteur theory advanced by Cahiers du Cinéma’s—and to position himself vis-à-vis other militant film collectives and their avant-garde agendas. The group thought of itself as a cell (like a political group or groupuscule), but in contrast to other film collectives and Maoist groupuscules that were organized around specific struggles (i.e., solidarity with female workers, with Chile or Vietnam, and so forth), DVG situated itself within the history of cinema by adopting the name of a pioneering radical filmmaker. None of their nine films are signed. Rather, members of DVG claimed authorship of them a posteriori in interviews or written documents.21 Godard and Gorin recognized that the Maoists had contributed greatly to revolutionary filmmaking by developing radically new aesthetic-political practices, but they felt that the Maoists hadn’t taken their confrontation with intellectuals and delegates far enough.22

Standing against the vanguardist logic that seeks to figure a future emancipatory image of the world, DVG’s movies show the political actuality; by describing their films as “materialist fictions,” DVG took a position with regard to “realist” and “materialist” politicized cinema. In general, left-wing films of the 1970s tended to film social movements live because they aimed to show the “reality” from which the members of the movements sought to emancipate themselves. This “realist” militant cinema was put at the service of good causes and addressed an activist public. It also depended on political reality; consequently, it could be said that its content (social figures in struggle) prevailed over its form. We must distinguish, however, this militant cinema (similar to socialist realism) from the materialist version, which sought to critique socialist realism and realism by transforming them formally; materialist film practice is thus characterized by observing reflexively the discourse of the cinematographic apparatus. As a practice, materialist cinema sought to overcome socialist realism by transforming it formally. This means that it attempted to demystify the process of cinematic production and the notion of the cinematographic image as a pure or objective register of reality, seeking to produce self-knowledge based on self-criticism. In the discussions that took place during those years about materialist cinema, the notion of the “objective whole” of the materialist Weltanschaung was based on André Bazin’s realist ontology. The critique of “objectivity” in cinema was crystallized in 1969 in a debate between two key publications in France: Cahiers du Cinéma and Cinéthique, the latter devoted to realism, indexicality, and reflexivity in cinema. (Cinéthique was heavily influenced by the films of Godard and DVG.) In contrast with materialist and militant films, the Dziga Vertov Group’s materialist fictions address the viewer didactically and, in a Brechtian vein, consider him or her as an active agent in the decodification of the movie.

In DVG’s first written manifesto, “Premiers Sons Anglais,” which appeared in the film journal Cinéthique in 1969, they began to outline their political praxis.23 In another text entitled “Quoi Faire?,” published in the British film review Afterimage in 1970, Godard described the militant program of DVG as underscoring a distinction between political films and films conceived politically. Political films, in Godard’s view, correspond to a metaphysical conception of the world: these films describe situations—for example, the misery of the world—and are thus in accord with bourgeois ideology and operate under representational logic. By contrast, “films made politically” belong to the dialectical conception of the world, which entails doing concrete analyses of concrete situations with the purpose of showing the world in struggle in order to transform it. Instead of making images of the world that are “too whole” in the name of a relative truth, making films politically entails studying the contradictions that exist between the relations of production and productive forces and producing scientific knowledge of the revolutionary struggles and their history. This program insists on a theoretical preoccupation with the relationships between world, image, and representation.24

Thus, DVG’s battle was fought on the field of a scientific theoretical practice, contesting Sartre’s conception of art and literature as the realms of the production of non-knowledge. That is to say that DVG’s aim of uniting theory and practice shows their attempt to bring art out of Sartre’s domain of non-knowledge. It also shows their effort to account for the explosion of information and the transformation of art into information. This led them to create semiotico-visual experiments, which became the basis of the pedagogy of their “blackboard films.” In these films, they aim to fabricate images that are not “too whole” and that carry a contradiction within them. They also aim to make simple or “just images” as opposed to making “images that are just,” by articulating disjunctions between “true sounds put on top of false” images. At the same time, their practice was based on a “productivist” model, seeking to achieve autonomy in the means of production and distribution of their films. With the hope of expanding their innovations to television, Godard and Gorin sought out the technical and financial alternative of televisual production. And even though DVG’s movies—British Sounds, Pravda, Lotte in Italia, and Vladimir et Rosa—were made with television producers—London Week Television, Munich Tele-Pool, the European Center for Radio-Film-Television, and RAI, respectively—in most cases the producers refused to show the movies. Nonetheless, television became for them a place to create new relationships of production, to try out technical innovations, and to create new relationships between viewer at text; they were also able to explore television’s pedagogical potential, which until then had been repressed by institutionalized television practices. Walter Benjamin’s notion of the “Author as Producer” is obviously a key influence here, as well as in DVG’s proposal (inspired by Brecht’s epic theater) to erase the dichotomy between form and content and to reconceptualize it in terms of technique. According to Benjamin, a progressive work of art will innovate technically at the same time that it places the means of production at the disposal of the masses—which translates in Godard and Gorin to technical innovations and to the pedagogical aspects of their movies.

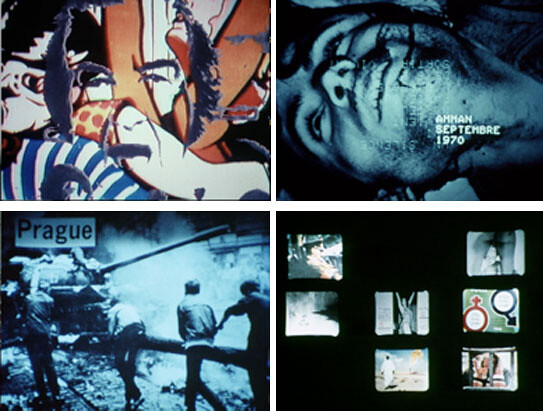

In ideological terms, DVG’s political line was Marxist-Leninism, also known as Maoism.25 In methodological terms, they applied the Maoist principle of contradiction or the “struggle of opposite tendencies” as a method in filmmaking which, as we have seen, consisted of studying concrete situations, outlining the contradictions inherent in them, and then applying various methodological grids for a comprehensive study of the situation from all sides: their films British Sounds, Pravda, Lotte in Italia, Vladimir and Rosa, and Until Victory (among other things) are concrete analyses of the political situations in Britain, Czechoslovakia, Italy, France, and Palestine, respectively.26 They applied Maoist materialism, which is a tool for understanding the development of a thing dividing internally and looking at the thing’s relationships to other things, focusing on self-movement and interaction. Mao designed this method because for him, complex things hold many contradictions in their process of development, and it is contradiction that makes them change. Mao’s contradiction differs from the principle of dialectical materialism, which claims that change happens through sublation into a higher unity; Mao claimed instead that change happens through small quantitative alterations that accumulate and eventually burst out into larger qualitative leaps. Following Maoist method, Godard and Gorin located a principle contradiction dominating a concrete situation and subordinated all other contradictions pertaining to the situation to the principal one.27 (For example, the main contradiction in Lotte in Italia branches into the contradictions of being a female middle class student who is also an activist.) After isolating the contradictions, Godard and Gorin built images according to these contradictions and proceeded to engage in self-critique. In summary, the application of the Maoist method for the acquisition of knowledge by DVG implied making “simple” images that reflected a double process of cognition and codification. This was a pedagogical enterprise in a Brechtian vein that maintained the fiction necessary for artistic discourse while at the same time distancing the viewer (and the filmmakers) from the ideological implications inherent to the concrete situations they analyzed in their films. Further, DVG’s films postulate the political actuality as a historicizing fiction, placing actuality beyond individual and collective events, turning “social types” (i.e., “worker”) and historical figures (i.e., “third world revolutionary”) into characters in their films. Historical specification becomes relevant here because DVG describes history in action, positing critically Maoist militants as the actors of history rather than passive followers of the universalizing discourse of “class struggle.” In these films Maoism is not taken as an ideological basis. Rather, it becomes both the code of representation and the method for making images; the films render Maoist practice literal by taking the materialist method à la lettre, separating themselves from the branches of “realist” as well as “materialist” filmmaking by calling their films “materialist fictions.”

I am indebted to Thierry de Duve, John Ricco, and Tom Williams for their rich insights and helpful comments on the various versions of this essay.

Godard’s practice of this period has been equated to terrorism by Serge Daney and condemned as nihilistic and iconoclastic by Colin MacCabe. See Serge Daney’s “Le thérrorisé (Pédagogie godardienne),”Cahiers du Cinéma nos. 262–263 (January 1976): 32–39, special issue on five essays about Numéro Deux by Godard; and Colin MacCabe,Godard: Images, Sounds, Politics (London: British Film Institute/Macllian, 1980). See also Raymond Bellour, L’entre-images Photo. Cinéma. Vidéo. (Paris: La Différence, 1990); and Peter Wollen, “Godard and Counter Cinema: Le Vent d’est” in Readings and Writings: Semiotic Counter-Strategies (London: Verso, 1982), 79–91.

What Is To Be Done?, printable edition produced by Chris Russell for the Marxist Internet Archive, 46. See →.

It must be noted, echoing David Caute, that in France the term “intellectual” designates a moral-political vocation that was affirmed during the critical climate of the Dreyfus affair, epitomized by Emile Zola’s famous letter “J’accuse.” According to the PCF’s definition, the notion of “intellectual” embraces writers, philosophers, scientists, scholars, artists, and people in the performing arts and liberal professions. In short, it designates society’s disseminators of ideas. See David Caute, Communism and the French Intellectuals, 1914–1960 (London: Andre Deutsch, 1964), 12.

André Breton, Manifestes du Surréalisme, édition complète (Paris: France Loisirs, 1962), 248.

See Michel Foucault’s preface to Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983), xiii.

Frederic Jameson, “Periodizing the Sixties,” Social Text 9/10 (Spring–Summer 1984): 182.

Walter Benjamin, “The Author as Producer,” New Left Review vol. 1, no. 62 (July–August 1970): 83–96. In an early version of this text, Benjamin cited the following quote from Trotsky but crossed it out before publication: “When enlightened pacifists undertake to abolish war by means of rationalist arguments, they are simply ridiculous. When the armed masses start to take up the arguments of Reason against War, however, this signifies the end of War.” (Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, Vol. 1, 362.) Trotsky advances two regimes of enunciation here: the speech of “enlightened” intellectuals, made up of “rationalist arguments” based on knowledge and theory; and the speech of the masses, based on Reason or causal explanations, that is, based on practice.

In linguistics, the suffix “-eme” indicates a structural unit of some kind in the lexicon, grammar, and phonology of languages. As Fredric Jameson has demonstrated, the leftist ideologemes mentioned here are part of a materialist theoretical practice that was derived from certain readings and practices of Marxism in the Sixties. See “Periodizing the Sixties,” 195–196.

André Breton, “Towards a Free Revolutionary Art,” trans. Dwight MacDonald, in Art in Theory, 1900–2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, 2nd edition, eds. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Malden, MA : Blackwell Publishers, 2003), 533. Originally published in Partisan Review vol. 4, no. 1 (Fall 1938): 49–53.

See Jean-Paul Sartre, Bernard Pingaud, and Dionys Mascolo, Du rôle de l’intellectuel dans le mouvement révolutionnaire (Paris: Le terrain vague, 1971); and Sartre’s three conferences held in Kyoto, Japan in 1965, published inSituations, VIII Autour de 68 (Paris: Gallimard, 1972).

La Cause du people along with J’accuse were journals directly linked to the Proletarian Left, a party supported by Sartre and other prominent intellectuals. It dissolved in 1973 due to internal conflicts.

Interview with Godard by Marlene Belilos, Michel Boujut, Jean-Claude Deschamps, and Pierre-Henri Zoller, first published inPolitique Hebdo, nos. 26–27 (April 1972); reprinted in Godard,Godard par Godard (Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma, 1998), 374.

In The Family Idiot (1974), his multi-volume work on Flaubert, Sartre combines existentialism and social critique to explore the situation of Flaubert in 1840, when the young writer wrestled with the opposing legacies of the Enlightenment and Romanticism: truth versus beauty, communication and the enlightening of others versus literature. Sartre studied Flaubert as part of his attempt to resolve the contradictions between bourgeois ideology and literature, searching for a classless writing, that is, writing as a matter of “se déclasser,” or expelling oneself from the bourgeois class. For Sartre, in Flaubert and in his own intellectual and political practice the autonomy of art is a matter of how a writer’s work should be understood in relation to his life and to the historical forces and social conditions that shape a writer’s life. See Sartre, The Family Idiot: Gustave Flaubert, 1821–1857, vol. 5 (Chicago: The University Press, 1993); and Graham Good and T.H. Adamowski, “Sartre’s Flaubert, Flaubert’s Sartre,” review of Sartre, L’Idiot de la famille, vol. 3, in NOVEL: A Forum on Fictionvol. 7, no. 2 (Winter 1974), 175–186.

Sartre’s position is similar to Barthes’s position on the “author function.” This is a conception of authorship based on depersonalization in favor of subjectivity in writing, implying that there is an intransitive relationship between reality and fiction. Thus, the writer function implies a subject separate from the real subject that becomes manifest in the here and now of the reader encountering the text.

What is Literature?, trans. Bernard Frechtam (New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1965), 5. First published in France in 1947.

See Pierre Bourdieu, “Sartre, l’invention de l’intellectuel total,”Libération, March 31, 1983.

Movement for the National Liberation of Palestine, founded in the 1960s by Yasser Arafat.

Quote from Manifeste: “En literature et en art, lutter sur deux fronts. Le front politique et le front artistique, c’est l’étape actuelle, et il faut apprendre a résoudre les contradictions entre ces deux fronts.” Reprinted in Jean-Luc Godard Documents, ed. Nicole Brenez et. al. (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2006), 138.

Many famous intellectuals were associated with the Maoists, who referred to these intellectuals as fellow travelers or “democrats.” Among them were Sartre (who lent his name to the directorship of La Cause du peuple), Simone de Beauvoir, Marin Karmitz, Katia Kaupp, Mariella Righini, Alexandre Astruc, Agnes Varda, and Gérard Fromanger, among others. See Christophe Bourseiller, Les Maoïstes: La folle histoire des gardes rouges français (Paris: Plon, 1996), 198.

For an account of Godard’s involvement with the French leftist press during his DVG period, see Michael Witt, “Godard dans la presse d’extrême gauche” in Jean-Luc Godard Documents, 165–177.

Jean-Pierre Gorin and Godard met in 1966 while Godard was filming La Chinoise, at a time when Gorin was associated with the Marxist-Leninist movement Union de Jeunes Communistes Marxistes-Leninistes (UJCm-l) at the École Normale Supérieure. It is said that after the events of May ’68, Godard sought to work with someone who was not a filmmaker. Legend has it that he and Gorin met again while attending a meeting of the États Généraux de Cinéma, a collective of militant French filmmakers founded during the events of ‘68. (For more information on the États Généraux assembly, see Cahiers du Cinéma [September 1968]; and Silvia Harvey’s account in May ’68 and Film Culture [London: British Film Institute, 1978]). Dissatisfied with the eclecticism reigning in the États Généraux, Godard and Gorin fled the meeting and founded the Dziga Vertov Group. According to David Faroult, Godard filmed two DVG films with Jean-Henri Roger: British Sounds and Pravda, both in 1969. In Faroult’s account, Gorin entered the picture that same year when he collaborated with Godard on the DVG manifesto and the filming of Le Vent d’est in Italy. (See Faroult, “Never More Godard,” Jean-Luc Godard Documents, 123.) Other militants who gravitated toward DVG included Gérard Martin, Nathalie Billard, and Armand Marco. According to Julia Lesage, Pravda was filmed in Prague with Jean-Henri Roger and Paul Burron. (See Julia Lesage, “Godard and Gorin’s Left Politics,” Jump Cut 23 [April 1983].)

Interview with Godard by Marlene Belilos, Michel Boujut, Jean-Claude Deschamps, and Pierre-Henri Zoller, ibid.

Cinéthique 5 (September–October 1969): 14.

See the original manuscript of “Quoi Faire?,” reproduced in Jean-Luc Godard Documents, 145–151.

For an extremely detailed account of the “political lines” followed by DVG in Pravda, Le Vent d’est and Lotte in Italia, see Gérard Le Blanc, “Sur trois films du Dziga Vertov Group,” VH 101 6 (September 1972). According to Le Blanc, the main political line that shaped DVG’s overall practice was theoricism, characterized by abstract analyses of real contradictions in social formations. Furthermore, each individual film was dominated by an additional political line. Pravda was dominated by “dogmatic spontaneism,” a political line followed by students who had quit the PCML-F (Partie Communiste Marxiste-Léniniste Français), objecting to its revisionism. Le Vent d’est was dominated by “right wing opportunism,” a line followed by those who tried to maintain “the organizations” (the UJC-ml) that attempted to take over the student movement in May ’68. Lotte in Italia was dominated by “leftist opportunism,” or the first line of the Proletarian Left.

For detailed descriptions of DVG’s films see Peter Wollen, “Godard and counter cinema: Vent d’est” and Julia Lesage, “Tout va bien and Coup pour Coup: Radical French Cinema in Context,”Cineaste vol. 5, no. 3 (Summer 1972); David Faroult, “Never More Godard,” ibid.; James Roy MacBean, Film and Revolution(Bloomington: Indiana University Pres, 1975); and Gérard Le Blanc and David Faroult, Mai 68 ou le cinéma en suspense (Paris: Syllepse, 1998).

See Mao Tse-Tung, “On Practice: On the Relation between Knowledge and Practice, between Knowing and Doing,” and “On Contradiction” in On Practice and Contradiction (London: Verso, 2007), 52–102; also available at →.

Subject

To be continued in “Between Objective Engagement and Engaged Cinema: Jean-Luc Godard’s ‘Militant Filmmaking’ (1967-1974), Part II.”