A complicated chain of events landed me in Los Angeles, on the west coast of the USA. It is a wonderful city, fascinated by itself to the point of being oblivious to what occurs outside of it. This is not the ideal place to be exiled to.

When forced to leave one’s home, an exile’s continuing struggle shapes him into a soldier—and a soldier can do little more than survive while he waits for the next battle, as he is less than likely to win the war. Los Angeles is an ideal place for soldiers, because there you have to fight against almost everything and everyone.

There are no events in the heart of LA; all events take place outside the city, so that it may only later reassemble them. In the meantime, all that exists in the city and its outskirts sits on a waiting list: events, jobs, careers, and potential futures. In such a proud city, undocumented and unnamed streets must avoid the center of gravity. These too must live in the suburbs where life is lived on a much smaller scale, far from the spotlights of the brightest city in the world.

I was an artist and a journalist, so it’s natural for me to think of Los Angeles as a dreamland—one in which I can no longer be myself. As in a dream, you exist by forgetting everything about yourself. You feel the need to constantly expose your inner self—until you can no longer wake up and be yourself again. I tried to stay connected to my past when I was there, but I think I failed. In LA, there is a powerful machine producing dreams, and you must only dream and do little else.

Los Angeles is one of the most famous cities on the west coast and probably the only one, although it is located at the end of the dreamland of the United States of America. Beyond Los Angeles, you cannot go further. It is the end of the world. The main issue in people’s minds there is the sun, and you must think about it, too.

The whole state of California is infected by the illnesses of LA. There are more than 35 million people in the state, but they have only one well-known newspaper. In my mind, this is a disaster—how can I stay in touch with my past and my country? Or, how can I survive the struggle of living in a city in which foreign policy has no place? At the time, I thought I must have been drowning in the wrong ocean. But I later realized that the same situation exists throughout America. It is not the America I thought I knew. Did I ever know it? I am now deep in doubt.

This realization led me to recall J. D. Salinger, who declared that “any art that becomes visible must leave the art scene.”

Regardless of what may happen in my home country, I am currently trying to recycle myself, to become an American. In order to achieve this, I had to break this huge country down into smaller pieces and places. This would allow me to build my own little illusion and live under its umbrella—free and ignored like an invisible and unknown person.

My time in the United States has taught me to live without any political hope. For to be part of the US political scene, one must follow strange procedures. I decided to stay away from these.

After spending many long and productive years as a writer and artist in Lebanon, I came to believe that anyone, in any country, must be involved in the politics of one’s native country, or at the very least its domestic affairs. And while it is natural in Lebanon for each person to have an opinion about foreign policy in both Lebanon and the United States, I realized on my first day in the US that the same was not the case here.

The Lebanese have to be concerned with their government’s foreign policy. The Germans, French, and Chinese may be in a similar situation. This concern could overwhelm the illusion that their countries have modern identities—built around metropolitan cities and their stable economies and societies. In America we do not live under the same onus. People here know and believe that the federal state can perform this role on their behalf, while individual US states behave like subordinate countries. The major difference between California and France is that in France, people need to think about the relationship between France and other countries around the world. In California, we don’t need to do so because we have a federal state whose servants do this without asking our help.

The federal state functions like a massive fence that surrounds all the states like a gated country. Outside the fence lies that which is “overseas”—an interesting label given to people and countries outside the paddock of the United States, allowing the American people to live their lives without caring about anything outside, or overseas.

The people “overseas” could be anything—enemies, aliens, non-humans, and, of course, friends. The employees of the federal state will take care of everybody, governing friends and enemies equally. Citizens have no need to worry about what may happen, and we can trade in whatever we want and benefit from the huge fleets of multinational entities such as FedEx or UPS. We have no need to worry for our safety, as the intelligence agencies and the Army will overcome all threats coming from outside.

The Lebanese must worry about their future each day, asking how they can maintain their sovereignty and standard of living. In the US we simply hire the federal state to answer these questions for us.

In a few months we will elect a president for this country. It is the first time in American history—at least since Eisenhower—that people around the world have held an American president’s picture over their heads while facing death. Yet we know very well that a strong economy and superb quality of life are what puts a candidate in the White House. Yet people living overseas have to think about their own countries without forgetting the United States, as well as other powerful countries; the unparalleled influence the United States exerts over events around the world places the identities of these other, overseas countries under real threats.

I now live in the federal capital, and have come to feel that Washington, DC is a unique city. It is a city “for rent,” which is to say that people who live here have recently moved here, and may move on to other places after a while. My neighbor who is a soldier may go to Germany or Kuwait next month. The President himself may return to Chicago or Hawaii next year, and all his staff will disappear with him.

Buildings in DC are durable and stable, and while the people who dwell in them are temporary residents who will probably leave eventually, the buildings themselves will continue to function and maintain the same look. This is not the case in other cities, where factories, shopping centers, and banks have disappeared completely. DC also accommodates other kinds of residents, and the people who occupy these permanent buildings are quite different from the people on the streets. On the street people experience the noise and lightness of everyday life, perhaps because they come from somewhere else, while the people who live above the streets are more serious and formal. Washington is the capital of the most powerful country in the world, but this capital is a rented one.

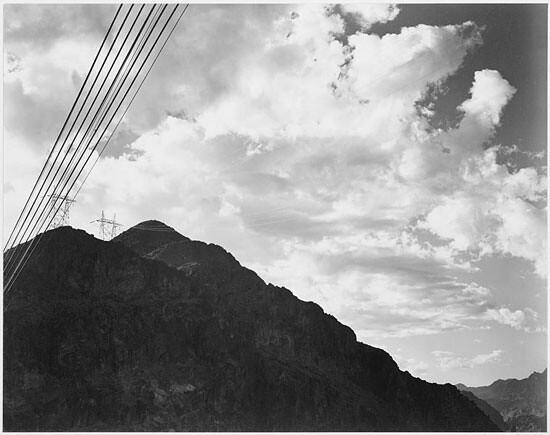

Between LA and DC stretches a very long freeway that cuts through deserted areas of a number of states. A traveler occasionally encounters small cities along the way, most of them built to serve those who are crossing the country.

A very basic infrastructure exists to serve people: motels, restaurants, rest areas, McDonald’s, and Starbucks. There are many choices for food and rest, but when it comes to safety, travelers have limited choices. People on the road cannot be themselves—they live a temporary life of sleep and travel, in which time has no value. Even if you happen to experience some pleasure on the road, it must be fleeting, like a dream—no long-term relationships, no time for indulging in a fine dinner. You may only sleep like a soldier who must be on alert for the next patrol.

You grow accustomed to choosing the fastest and safest possible route. McDonald’s, Starbucks, Subway, and Days Inn become the kings of the road, and you must spend your trip entirely dependent on them; you lack the luxury or the time to choose something better. This leads you to conclude that this empire is exactly like the federal state, full of transient people and located nowhere.

You also notice that FedEx ground service is the king of the road. Millions of trucks with the FedEx logo pass by, moving goods regardless of their type or quality. While the goods may belong to locals of each state, FedEx itself is an honored citizen of the federal state.

I did not have a smartphone on my first road trip from LA to DC, so there was no internet connection to help locate myself or find food and accommodation to suit my taste. On my second trip, I did have one, but it did not make any difference in the end. I was able to find what I thought to be a good restaurant and hotel, but ended up in the same chain I stayed in before, which now came highly recommended on social media sites by its very owners and managers. Google told me exactly where I was and whether the amenities around me were good or cheap, but google, like FedEx, is a huge container that does not care about its content.

After a long search one chooses what one already knows—McDonald’s, Starbucks, Subway, and Days Inn. It is a trap no one can avoid. I couldn’t help but notice that American people don’t like McDonald’s or Starbucks as people elsewhere do. I think they are protecting themselves from being erased by such a huge system capable of destroying not only their identities but also their interests. As a newcomer, I probably shouldn’t take all of this too seriously.

Important elements of the empire exist across the entire world, and like McDonald’s and Starbucks, we feel the presence of the US Army everywhere, both within the United States and throughout the world. US Army bases inside the states are also located in deserted areas. The US military lives its life on the seas, overseas, and in marginal areas of states—areas of no interest to anyone. In New Mexico, google planned my journey to the airport. Without much choice, I followed its directions and found myself at a checkpoint. I turned around to take an alternate route and came to yet another checkpoint. When I asked the soldier which road I should take and why google maps keeps sending me to checkpoints, he told me that this road used to lead to the airport.

As the airport’s vast spaces had not been used in ages, the Army acquired it as a military base. The US Army exists wherever the people of this country do not want to be.

But what really interests me is how those who would like to serve in the federal government must pass a security clearance. In order to become a federal employee one must leave one’s rights as a citizen behind, and become unable to express opinions while showing absolute respect for the terms of one’s contract. The same goes for employees of google and Apple.

You must move from your hometown to wherever they want you to move: San Francisco or maybe DC. Once you are hired, you cannot be found. As with the Army, corporations like google are gated communities as well; they keep moving to nowhere. As a nation on wheels, the United States is untouchable because it is a nation of employees, without citizens to serve or rule. Since these employees live in non-places, they have no homeland to be concerned about. Each one of them is moving continuously, and few know what happens in their moving communities.

On the contrary, the people of the individual states live in specific homelands, and they are citizens, not employees. But as citizens, they are barred from involvement in the foreign affairs of their country. It seems that the only way to be involved is by standing in total opposition to the official foreign policy. With this, I finally came to understand where Edward Said was coming from on the issue of being on the margin: in order to be heard, he had to become an advocate of Islamic fundamentalism. He had to push his stand as an invisible citizen to the extreme in order to be visible. From the margins of US politics, he became an acting attorney for Evil in order to have the basic voice of a citizen.

Federal employees live inside DC’s high buildings, silent and invisible behind their dark windows. Being above the noisy streets grants them a full view onto the city; from that spot, they resemble gods watching humans on earth. I now have the courage to declare that to be an American you must believe in it like a religious faith. Here we are all believers—our social classes and financial capabilities matter little. In California the lifestyle, benefits, and exposure to innovation and high technology are utterly different than they are in Montana. But what joins the people of both states is not the oath of citizenship itself, but rather this faith in being American.

I may argue then that we, the people of the other states, believe in the United States as a religion, and we don’t pursue the happiness that Thomas Jefferson spoke of. We rather seek the illusion of living in the Garden of Eden—on the west coast where things do not happen. There, where the earth itself comes to meet its end, we may only remember things and events.

In any case, I left this paradise to live on the east coast and become an American citizen. It seems, however, that there’s no way to leave: I found the east coast to be absolutely the same as the west coast.

Beyond citizenship, one must make the choice to become an American; it is not something you gain by birth. As adults in America, we are more like the people in the Mayflower. Everyone on board has their own individual memories from previous lives. The only thing they have in common is that they face the unforeseen. And while they must agree to face the challenges together, each turns back inward in their private time. This is truly the perfection of individuality, yet this individuality works only in private. As if in a huge Mayflower, we live in a place where everyone has very personal interests, memories, and past lives. No one wants to share the density of their past.

America as a religion urges us to be ourselves. At the immigration office, the officer tells the applicants: regardless of where you come from, you must be proud of your new identity, all of us here come from elsewhere and all of us are American now. The fact is that none of us in America are able to be American, but we still have the choice to be Lebanese or Palestinian or Chinese under the federal flag. America is the only country that seems large enough to hide anyone and every story.

Every person in America has a painful story, but knows very well that nobody wants to hear it. Los Angeles sometimes creates stories that can be shared—about destiny, madness, pain, and death. But we know that there are only a few stories that LA is interested in. For this reason, an exiled person has no choice but to speak about his problems and repeat the story of where he comes from. In order for people to listen, it must be just another story, and by no means a special one.

The writings of J. D. Salinger do not seem to me to be interested in actual stories, for Salinger was more preoccupied with the notion of generative storytelling—it was words, and not language, that produce the ultimate drama. I sometimes feel that Salinger’s characters use the wrong words to describe their circumstances—expressing anger, envy, and fear without any suggestion of the causes and motives of these feelings. In his book The Culture of Fear, Barry Glassner shows us that almost all Americans suffer from one illness or more; he also suggests that they project a fake malady to hint at their suffering from something else. There is a high fever that leads us to go to the gym, take vitamins, and become obsessed with healthy food. It is an attempt to make us live longer in the hopes of finding happiness. Living in these conditions must push Americans to find their small communities: Latin, vegetarian, African, and so forth. Does this explain why the United States could be the only place on earth where I can be more Lebanese than in Lebanon? The same may apply to Palestinians, Chinese, and Latinos.

The next question that comes to my mind is: What art can we make here? I believe that we can only tell stories, and only ones about coming or going elsewhere. I don’t think we can tell stories if we only live here. Such an art must be global, and its audiences must acquire the necessary knowledge to be able to react to these stories. To make American art, we have two choices: to be aliens from outer space with total knowledge and no empathy for what we know—which explains why it is only in America that movies such as Star Wars and The Matrix are made. Or we transform ourselves into images of ourselves and allow the art scene to consume our flesh and blood for the sole purpose of becoming an image—as Michael Jackson did in his personal life and on stage.

To be exiled in America we must exile ourselves from our bodies and our memories. Otherwise we will stay deeply inside ourselves, as the people on the Mayflower did as they reached the eastern shores, never to share their inner thoughts again. We must split our inside and outside—hide our inside and only show the outside that tells what we plan to become. This is, after all, a nation of the future—nobody cares about past and present. It is for this reason that the USA remains the most powerful nation on earth.

The New Ten Commandments:

1. Don’t forget to pay your dues.

2. Get a loan and repay it.

3. Keep saying that you plan to have the perfect body.

4. Keep saying that you will become rich and famous.

5. Take lots of vitamins.

6. Learn how to talk and not converse.

7. Get an iPhone. The Nexus and Galaxy phones are acceptable alternatives.

8. Write reviews of your favorite restaurants.

9. Create your small community.

10. Forget these commandments on Saturday night.