Since the early 1990s Adam Curtis has made a number of serial documentaries and films for the BBC using a playful mix of journalistic reportage and a wide range of avant-garde filmmaking techniques. The films are linked through their interest in using and reassembling the fragments of the past—recorded on film and video―to try and make sense of the chaotic events of the present. I first met Adam Curtis at the Manchester International Festival thanks to Alex Poots, and while Curtis himself is not an artist, many artists over the last decade have become increasingly interested in how his films break down the divide between art and modern political reportage, opening up a dialogue between the two.

This multi-part interview with Adam Curtis began in London last December, and is the most recent in a series of conversations published by e-flux journal that have included Raoul Vaneigem, Julian Assange, Toni Negri, and others, and I am pleased to present the second part in this issue of the journal in conjunction with a solo exhibition I have curated of Curtis’s films from 1989 to the present day. The exhibition is designed by Liam Gillick, and will be on view at e-flux in New York from February 11–April 14, 2012. In Conversation with Adam Curtis, Part III will take place as a live interview at e-flux, New York, on April 14th.

—Hans Ulrich Obrist

→ Continued from “In Conversation with Adam Curtis, Part I.”

HUO: I wanted to ask you about collage, and the way you use archival film footage as a storytelling technique, but also as a way of revisiting the recent past. You’ve mentioned before how important this extraordinary BBC archive has been for providing material for your films, but how did you arrive at using the archive in this way? Was it something you had in mind when you began working at the BBC?

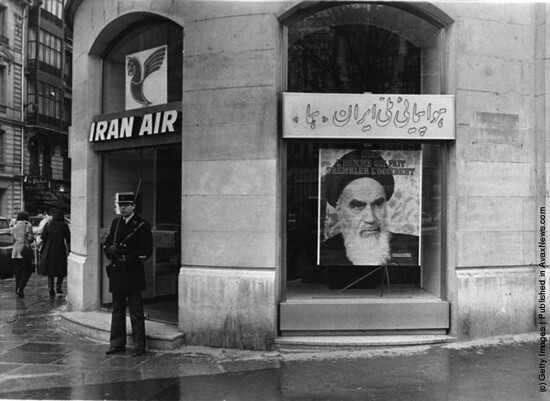

AC: Well, not really. One moment when I realized that I could use it was when I made a film in 1989 called Inside Story: The Road to Terror, which was really my first experimental film, and the moment when I found a voice. The film was about the Iranian Revolution and the French Revolution. When you’re a journalist, you often do things out of desperation, because you’ve got a deadline and you’ve just got to do it. With that film, I was in a really tight spot—I’d been asked to make a film about the torture in Evin prison of the Iranian Mujahideen—a bunch of not very nice leftists who had originally started the Iranian Revolution with Khomeini, and who Khomeini then simply massacred or imprisoned in the early 1980s after he assumed power. I had been commissioned to make what was then considered the correct—and “balanced”—kind of documentary about this, which is basically you go and make a moving film about how terrible torture is, to which the audience then go “oh dear, how terrible.” And that’s it. But the problem was that as I researched the subject it became more complicated. I had great sympathy with the individuals who had been tortured—but not with the Mujahideen, I realized once I investigated them that I actually didn’t like them very much. I thought they were a bunch of narrow-minded dictatorial leftists who did a lot of terrible things themselves… And yet, I was stuck with this film. And I thought, you can’t make fifty minutes of people in silhouette talking about torture. People do make films like that, but, without trivializing what they’ve been through, I wasn’t interested in that approach. So I said, well, it’s 1989, and I’m in Paris interviewing a lot of these people who have fled there. And I suddenly realized, of course, that there were two revolutions that went down parallel, but also contrasting, roads to terror. Let’s make a film about that. And so I spent a week cutting the two together, completely experimentally. The people I was making it for just thought I’d gone absolutely mad.

HUO: So that’s the beginning of your methodology for bringing things together!

AC: Right, it was desperation! But it was actually quite serious. I was saying, look: there is a history of a revolution 200 years earlier. And there’s a history of a revolution that happened ten years earlier. Let’s compare and contrast. So, in academic terms, I wasn’t being silly, though I did do it in a completely odd way. There was one shot where I literally grabbed the camera, because I was bored driving through Paris, going into the very underpass where Princess Diana would later die, and just started filming out of the car. The shot goes down and enters the darkness of the tunnel. And I took this shot, late one night, and cut it to Beethoven’s Fidelio, the prisoners coming out of the darkness, and then went to a silent movie about the French Revolution, and I made it very romantic. When I sent it in, everyone hated the film, just loathed it, and they weren’t going to put it out. They thought I had gone mad, because the traditional liberal approach is to go and make what they called then a “moving documentary about torture.” I had done that, but it was only five minutes of the fifty-minute film, right? But before I could find out whether they were going to make me recut it, Alan Yentob, who was the Controller of BBC2 at that point, saw it and he went, oh, I love it, let’s put it out. And he did.

HUO: So he was the first to understand what you were trying to do.

AC: It was great. That’s where it started. And from then on, Alan Yentob just backed me. He was really, really good to me. Then I went and made a six-part series called Pandora’s Box.

HUO: And Pandora’s Box ties in with what you said about rationalism before.

AC: Yes, well, I think that the generation ahead of you always tends to set you puzzles—and the thing that always puzzled me about the post–World War II generation is: Why did they go from being optimistic about science and rationality, and things like planning, to a dark, almost apocalyptic pessimism in the 1970s? It’s an incredibly quick switch, and the example I just gave you about the correct liberal way of doing a film about torture is a good one. You go out and elegantly film people, sometimes in silhouette, recounting terrible, horrible experiences—combined with haunting, Arvo Pärt–style music over bleak landscapes. And that’s it. I’m not being cynical or flippant about the peoples’ experiences—but I just think that the editorial approach was to wrap those experiences in a rigid melancholy that traps everyone—audience, filmmakers, and the tortured—in a feeling of helplessness. And it’s called moving. So I decided to do a series that went back and looked at the rise and fall of that optimism about science and rationality and planning to try and understand more why it failed. And of course I found out pretty soon how difficult it was going to be. In one case I stupidly decided to make a film about economics, about how politicians became possessed by the idea of how economics and economists could “scientifically” show them how to manage their societies. Now the reason why television people tend not to do this is because both in terms of narrative and in visuals, economics is both abstract and very boring. This is also why economists get away with murder: it’s so boring that no one is watching them. Part of my film was about monetarism and Mrs. Thatcher, and I had quickly realized that I had a problem on my hands. So late one night, I just started to play. I put jokes in. I made very silly jokes about one of Thatcher’s ministers, Sir Keith Joseph, who I’d interviewed, and it was just terribly funny. I even included some shots of a squirrel handing out money that I’d found somewhere. I worked all night and went home at six in the morning. I had no idea what I’d created, but it was very funny. And then it won two BAFTAs. It was great, because I realized that, provided that you are intellectually clear in what you’re saying, then you can be as silly, and as emotional as you want.

HUO: Lets talk about The Living Dead?

AC: The Living Dead was three films about memory in the construction of history. By this point, I knew that the past was open for reconstruction. So, I wanted to go back and say, well, how was this recent failure constructed, and why? And unfortunately, the first film I decided to make was about how our memory of World War II was constructed, which was arguing that the fact that it was a good war in our memories doesn’t mean we’re good people. This invited a number of attacks on me, with the Daily Mail calling me a Nazi. Allison Pearson called me a Nazi on television. I went from being this sort of, like, super groovy film director to being the most evil person in the world. It was an extremely good lesson for me. It wasn’t fun, but it taught me a lot.

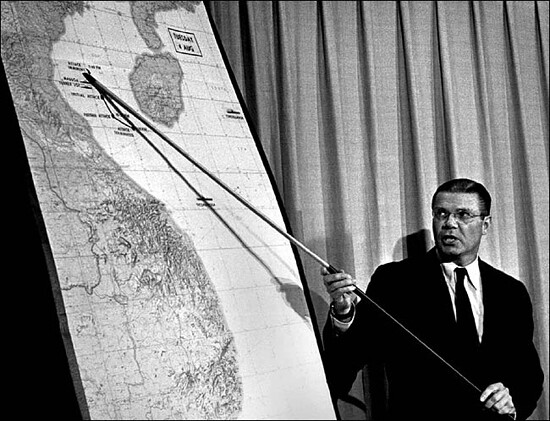

HUO: It’s interesting that the artist Liam Gillick has also worked a lot on this question of rationality and McNamara. In urbanism, we also saw the failure of the idea of social planning, which is related, wouldn’t you say?

AC: Yes. I mean, that generation of technocrats—from architects to economists to people at the RAND corporation—genuinely believed they could plan things, didn’t they? That was the project that I was dealing with in Pandora’s Box, where you have large parts of the twentieth century that are about this idea of rationality. Of course, rationality and scientific rationality are absolutely brilliant, and we wouldn’t have the world we have today without them. But after World War II, there emerged this idea that you could take scientific rationality and apply it to all social and political questions. And that led to unforeseen consequences, because you can’t do that, whether within the Soviet plan, or by mathematically working out which villages to bomb in Vietnam, or to work out an economic plan. I came in around the end of the ‘80s and the early ‘90s when the failure of that project became apparent, and I wanted to know why. McNamara’s generation really believed that they could “scientify” everything, technologize and rationalize everything. And that didn’t work. But it doesn’t mean that building great buildings is wrong. And it doesn’t mean that scientific rationality is wrong. That’s the important thing to realize. And that’s what the series argued, that the failure of the project didn’t mean that science was “bad,” it’s just that there are certain areas that it cannot be applied to, above all the chaotic and dynamic world of politics and history. But that’s not how the postwar generation took the failure. Two very powerful groups in the West who you would have thought were totally different in outlook—the conservatives and the liberal hippies—both reacted to this failure in a very similar way. They said, well, this means that you can’t plan anything—science is wrong and rationality is wrong. The liberals then sit there and say, “oh dear”, or retreat into mysticism, while the conservatives then grabbed the initiative and said, well, all you can really do is allow the free market to flourish and order will come out of that. And then, in the 1990s, a surprising number of the hippies joined the conservatives in this—especially in Silicon Valley. But I think this is wrong. In the end, I think rationality’s all you’ve got to work with. It’s just that there are areas where you can’t apply it. In a way, we threw the baby out with the bathwater, and this reaction to the failure of the idea of using planning to change the world then had a terrible effect on politics, it massively devalued the role of politicians. In the face of this retreat from the dynamic idea of progress and changing the world, politicians became instead managers of society as it is, and they came to see their job as being to simply leave the world to go on as it is—with all its inequalities and imbalances of power. And in response to that, we, the electorate, began to turn away from the politicians and scorn them because we felt their loss of self-confidence. But politicians are still incredibly powerful—they are lawmakers. Look at how they used their power to take over giant institutions—like the banks—and rescue them during the economic crisis in 2008. They have this enormous power, yet in our minds they are nothing. And in response to that loss of prestige and influence, politicians then cast around for something, anything, that could restore their power and influence. And what I argued in The Power of Nightmares was that they stumbled on fear. It wasn’t so much a conspiracy as something they discovered in the wake of the attacks in 2001 as a way of restoring their sense of authority and dignity, because instead of promising a better world and asking for your trust, which we no longer believed, they found they could say instead, “no, actually there’s something really terrifying out there in the darkness which I, the politician, can see, even if you can’t, and I can protect you against it”—and this restored their authority. But only for a brief while because I think that’s now failed, and they’re seen as undignified failures yet again. There was a grand political project after World War II that wanted to change the world for the better, and it failed because it adopted rationality at too high a price. It tried to apply rationality too broadly, suffered the consequences, and became trapped. My argument is that you want to examine why something went wrong in order to recover it. So this failure doesn’t mean that we can’t go back and recapture politics, and make it grand again.

HUO: In your conversation with Errol Morris, you talk about politicians and your odd interest in Henry Kissinger.

AC: It’s what I always say when people criticize me for being a leftist: Well, then how could I make Henry Kissinger one of the heroes in a film like The Power of Nightmares? I doubt that I could make a film that actually praises Kissinger. Kissinger did a lot of bad things. But his view of politics is resolutely pragmatic, because it’s about power. The world operates through power. And I was contrasting him to the neoconservatives who believed that the world is actually manufactured through myth, through stories. And in that series, I was looking at the consequences of that. I just think that in a brutally realistic way, he sees the truth.

HUO: The brutal truth?

AC: Exactly, which is that power exists. If you have a world with scarce resources and inequality, power is inevitable. It’s a fact. I think some of the choices he made are not ones that I would support in any way. But he had a sort of brutal realism to him, which I respect. And you know, he would have never gone into Iraq. Kissinger is like an ancient ghost from another time that says, I am powerful, and what I do can have some effect. But you have to look at it in this hard, realistic way. This is not to support what Kissinger did, because actually, politically, I disagree with him. But in his attitude, he’s like a voice from before our age of individualism, where what counts is what you, a political or military leader, believe about history. It’s rather like in Tolstoy’s War and Peace, where there’s Napoleon who thinks he can change history and then there’s this other character who I’ve always rather admired, Marshal Kutuzov, who is Napoleon’s opponent, an old general who everyone despises, but in the end saves Moscow. His view is that the events of world history are just chaotic, so complex. You can never understand them. But there come moments in the chaotic flow of events when the mist of confusion suddenly clears and it allows you to see that if you act at that moment in a particular way, you can shift your position, turn the pivot your way. And then the mist will roll in again. It’s about how to use power creatively in a dynamic world—how to turn history your way for a moment. But, unlike Kissinger, you are driven by a moral vision of what kind of society you are trying to achieve.

HUO: Whereas for Kissinger any act would be like a political hyperrealism?

AC: Yes. If you look at the world through Kissinger’s eyes, it would look like one of those glaring hyperrealist paintings from the 1970s. Politics becomes unreal in the face of being despised, and politicians try to regain their momentum by creating myths. But politics will not go away, because the only way we change the world is through politics, through the ability to change the law. If you can change the law, you can change the world. Yet we despise politics. And the really interesting project of our time concerns how politics can recapture a sense of taking us somewhere else. No one’s discovered that yet. But it seems to me that most artists aren’t interested in politics.

HUO: I think artists are increasingly becoming interested in politics again. For example, we are seeing a return to the situationist strategy of détournement, where you can appropriate something and turn it into its opposite.

AC: Yeah. But actually, I’m never convinced that things work like that. Things get repossessed very quickly, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. People like Godard steal from Hollywood, but then you see Hollywood stealing his ideas back. Bonnie and Clyde is suffused with Godard’s ideas of filmmaking, but popularized. And, I know this is not the right thing to say, but I prefer something like Bonnie and Clyde to Godard films. In a funny way, I think they are cleverer.

HUO: It’s interesting how these ideas can return to change the work. Last week, I had a conversation with Eric Hobsbawm who spoke about Marx, and it touches on The Communist Manifesto as a literary statement that changes the world. Likewise, the history of the avant-garde is full of manifestos that wanted to change the world. And the neo–avant-gardes of the 1960s revisited this idea of manifestos in art, architecture, and literature. But we now live in a time which is more atomized into these constructions of isolated subjectivities, as you were describing before, that make it difficult to collectively imagine the future. So I was curious as to whether you have a kind of manifesto.

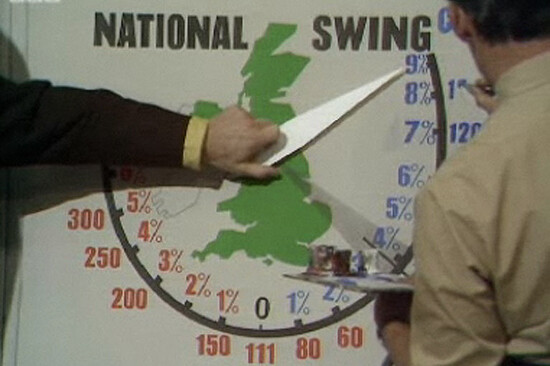

AC: No, I have no manifestos. I don’t think that’s what journalists should do, and I mean, I critically analyze the past in order to cast some light on the present. I can’t predict what the future’s going to be. And also, in an age of subjectivity where everyone lives inside their heads—I mean, how can you have a manifesto? Everyone has their own manifesto now. I think this is the other thing that politicians have come to realize, that in an age where people are obsessed by their feelings and what is inside their own heads, and tend not to look outside themselves and join things like trade unions or political organizations, then power comes from finding out what is inside peoples’ heads, not from encouraging them to look outside. So knowing what they want is the driving force in politics, mostly through focus groups. In the face of that, how can you have a manifesto? Everyone’s head is a manifesto. And politics has got caught up in trying to juggle all those competing individualized manifestos. I’ll tell you where the modern manifesto lies. The modern manifesto, in our society, probably lies within the heads of about 80,000 people in this country. And those are the people who live in the marginal constituencies in this society, because knowing what those people want—and promising to deliver it to them—is the way to power. In a way, much of our political future is in the hands of those who live in the marginal constituencies, and they are the people who haven’t made up their mind in the last week of voting before an election. In a focus-group–driven democracy, which is essentially a consumerist democracy, what’s in their heads, what they want, becomes the manifestos of the parties, because those are the people that will get them into power. Everyone else has sort of balanced off, the committed rightist balancing the decided leftist. And that leaves the swing voter. And what’s in the swing voter’s head is the manifesto of the party. And Blair’s manifesto in 1997 was a perfect expression of what was in the swing voter’s mind, which was a desire for—you can read it, I’m not going to go through it. How do you have manifestos in an age of subjectivity? Manifestos are in the past, which, I would argue, the artists nostalgically look back to. And to be honest, I think the only way you are ever going to break out of that is to create a vision of an alternative future that is so inspiring and attractive—and more fair—that people will look outside their own heads and say: yes, I want that. But the sad truth is that no one has any vision like that at the moment. The Left has completely failed in the wake of the economic crisis. I mean completely—it’s quite shocking. I’m sure there is something lurking out there on the margins of society, but no one can see it yet.

HUO: And for the moment, for example at Wall Street and the St. Paul’s protest, is there no manifesto?

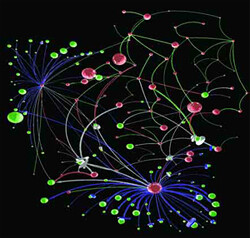

AC: I’m very, very, very cynical about this. I got into trouble, because I wrote an article in Observer criticizing them, saying that they are like office managers—they’re obsessed by process. And their idea, which they have, of self-organization, I just rather cheekily pointed out that actually that’s also a mirror image of the free market. Their idea that somehow you don’t need leaders, you just have the group coming together and creating a new kind of order. They are trapped by that. I mean, I mustn’t be too nasty about the protest because I actually sympathize with what they’re saying. But, to be brutal, I mean, to be brutal, and I have talked to some of them. A lot of the leaders of the protest movement, especially here in Britain, come out of academia. Some of them are PhD students who studied what is called network theory. And network theory is, I think, dangerously limiting because it leads you to both a very narrow and disempowering idea of what democracy is. They have a vision that comes out of things like the commune movement of the 1960s, fused with some anarchist ideas—that imagines an alternative way of organizing society in a non hierarchical way, networked together where everyone interacts through feedback processes to create a kind of order. Many of them look to the internet as a model of this—and dream of a world without elites. I’m afraid I think this is a dead end—it also oddly echoes the very thing they are against, the invisible hand theory of Adam Smith—but it’s really a dead end because underlying it is a static managerial theory. It says that the feedback between all the individuals will create order and stability, and that’s it. To go back to what we were talking about earlier—about the limits of rationality in politics—this kind of managerialism cannot cope with the dynamic forces of history that politics has to deal with, and it is also totally uninspiring as an imaginative vision of the future. And I am quite shocked by how the left as a whole has completely failed to capture the mood of fear, uncertainty, and doubt that rose up in the wake of 2008. It is an extraordinary failure not to have come forward and said—“you thought it was good to be on your own. But now, when things go bad, it’s frightening. But don’t be frightened. We’re going to create something that will take you out of yourself and out of that fear, and make you confident, because you’ll be with other people, and together we’re going to create this.” That’s how you do it. And that’s where the new politics is going to happen. And in a way, the protest movement by obsessing over process, talking constantly about non-hierarchical systems of organization, just like I hear managers talk in the BBC, is like a roadblock stopping that happening. So that’s what I think. It’s a failure of political imagination dressed up in smart geek philosophy of systems organisation. I’m also deeply suspicious of the cyber-boosters who for the last year have been endlessly saying that it was twitter and facebook that created the Arab Spring. There’s a new kind of patronising orientalism creeping in—“it’s our western technology” that created the revolts. No it wasn’t—of course they helped to an extent, but the real motive force was a mass wave of emotional fury and anger born out of suffering and indignity. And notice that it is now the Ikwhan—the Muslim Brotherhood—who are making the running, for the simple reason that they have ideas, and they have a vision. It’s a very conservative one—but it’s a lot more than the liberals have.

HUO: And you wrote a text titled ‟How the ‛ecosystem’ myth has been used for sinister means.” in the Observer about that.

AC: I wrote a very long piece back in May, and they got really upset. I got massively attacked on Twitter. So I then gave an interview attacking Twitter. I said that Twitter was the absolute equivalent of socialist realism under Stalin because it was a perfect expression of the ideology of it’s time, and Twitter expresses the individual, what I feel is the mort important thing. And socialist realism expressed the vision of collective planning. But neither of them show the architecture of power that surrounds that. So, I did that, and I got even more attacked. But it was good fun. It’s part of my job. My job is to provoke. But, to be honest, to be brutal, the protest movement has been captured by academia. They are academics. Theories behind them haven’t got the sort of dynamism of politics. But then the other way of looking at this crisis is that, while a lot of people are hurting—especially in America, more so than here in the UK—a lot of the apocalyptic predictions may not be as apocalyptic as we think, because it’s possible that they are actually being manipulated by people in the market who are using them to their advantage. In fact, I think a lot of the apocalyptic fears in the market as it goes up and down across Europe with the Euro are actually being pushed by a lot of traders who are benefitting massively from this. You go short on a country, and then make apocalyptic predictions. You can make vast amounts of money from that. So the system is actually pushing its own destruction. I think the real question at the moment concerns democracy, not the protest movement. I think the most interesting thing concerns the very people I made Pandora’s Box about, because this idea of technocratic rationality has returned in a weird and distorted form to Europe, and it is actually ending democracy. In Greece they’re actually refusing—they’re saying, no, we can’t have democracy, because the alternative is unthinkable.

HUO: In All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, you also talk about this organizational utopia and what went wrong with it. What triggered All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace?

AC: I wouldn’t put it quite like that, in reality I just found a good and interesting story. I discovered that the man who invented the idea of the ecosystem was a British biologist who had no evidence, but literally read Freud and took a mechanistic view of the mind as a network. It’s a fantasy that we’ve long ago forgotten, and he literally projected it onto nature and, without any evidence, said, this is nature. Ever since I’d made the third part of The Century of the Self, I’d begun to realize that many of the ideas that came out of the hippie movement had deeply conservative influences. I’ve always thought that many parts of the green movement have become deeply conservative as well. I thought that would be really interesting to examine. It’s no different from how many of the films I make start. I’m researching one area, but then I stumble on a story that takes you off elsewhere. Like when I set out to do The Power of Nightmares, I had no intention of doing anything about terrorism at all. I was at the history of conservative ideology. And I was interested in Islamism as a conservative ideology that began back in the 1940s. I discovered that the man who’d invented the modern version of Islamism, Sayyid Qutb, had his own epiphany at a dance in a small town in Colorado in America in 1949, and out of that came the writings that would later inspire, in a weird and corrupted form, the people who flew two planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001. And I thought, well, that’s the beginning of a novel: a young, lonely, shy, neurotic Egyptian at a dance in Colorado, in the United States, in 1949, gazing at the dancers and seeing them as a corrupted idea of individualism that could spread to the rest of society, then going home and writing the beginnings of a series of tracts that would inspire the political movement of modern Sunni Islamism. Well, I thought, that’s really good because it takes you into a big subject in a new and fresh way. It was like learning that Edward Bernays was Freud’s nephew, and invented public relations. That was again like the beginning of a fascinating story that took you into the history of PR and advertising in a new way. But you mustn’t make too much of this, because this is how journalists work. It may not be how artists work, but journalists aren’t interested in anything unless they find a story. Machines of Loving Grace was basically the series of stories that I had discovered were all about the machine ideology and how it had penetrated our world in different ways. As for the ecosystem one, I was fascinated by the way this biologist had taken a model of the mind born out of electrical engineering and applied it to the whole of nature. But when I also looked to Richard Dawkins and the origins of the selfish gene theory, I discovered that it also went back to an amazing story of an American computer engineer who came over to the UK in the 1960s, dreamt up this incredible equation, and then committed suicide when he realized that it denied the existence of God. Again, I realized that the selfish gene theory is actually not a biological theory. It was a computer machine theory of code. And what I realized with this collection of stories was that theories that appear to be biological theories of the world are generally understood to be somehow more real, and therefore true, because biology is the science of our time. Anything that’s biological, we believe is true.

HUO: And the twenty-first century is widely considered to be the century of biology.

AC: Exactly. And I’ve always been suspicious about this. So what I was simply collecting were stories that said to me that what appears to be biological, like the selfish gene, is actually just an idea borrowed from computer coding, and comes from DNA. It’s quite obvious now from research that DNA is actually not the simple “code of life”. It is part of something far more complicated inside the cell involving RNA actually editing the DNA sequence—which raises all sorts of odd and forgotten ideas about inheritance. Scientists are still completely baffled by how the cell really works. But my focus in the stuff I do is not really the science, but rather how simplified, and often out of date, scientific theories are taken and transformed into metaphors that are then projected onto society—and are in turn used to bolster what are essentially political schemes.

HUO: What about this pivotal cybernetic moment in the film? How does that idea connect to this relation between biology and nature?

AC: Well, cybernetics is fascinating. But actually, I think it’s part of the real serious problem of our time. Because cybernetics is, again, about how you can look at the world as a series of systems that manage themselves. It’s part of this idea that’s risen up to say that our aim shouldn’t be to change the world, but to manage it. It suits a very conservative ideology, the market ideology—we just want the world to keep on renewing itself and staying as it is through the endless reconnection of individual desires. And cybernetic models are at the root of that. It’s a managerial idea, that your aim, just like in the Cold War, is to maintain stability. I think that the Cold War, cybernetics, and the vision of “natural webs” supply a lot of the underpinning to this very conservative ideology, whose proponents say, how can we be wrong? We just want to create a stable world—and, do you know, it must be right because it imitates nature.” But they are stopping people who want to change the world. They’re actually even stopping people from having the framework to think that they could change the world, because if you look at the protesters now, what they spend their time talking about is how they can organize themselves. They’re managers. They’re not doing what the utopian socialists did in the 1830s, when Balzac was writing, when people like Saint-Simon or Charles Fourier, before Marx, were coming up with extraordinary, weird dreams of alternative futures. These guys were nutty. Fourier believed in love as the dominant force, and he wanted a group of people in his new society called “fairies” who would look after heartbroken lovers. It’s completely mad! No one dreams of a future now. Or talks about love—because it isn’t part of the dominant economic and management discourse of our time—which at heart is a narrow, completely utilitarian one.

HUO: If you think about managerial reality, it’s interesting that Buckminster Fuller is usually considered to be a utopian thinker, but you actually get the feeling he’s more like a manager.

AC: Yes, Buckminster Fuller was one of the early managers. But what else was he doing? He was a great and wonderful con man, Buckminster Fuller. Watching him speak on all the films they made about him back in the 1960s—he is extraordinary, you think you and I have scatty brains? He makes us look completely logical. He was a wonderful con man. What he was essentially doing was giving you models for how to manage the world. And actually, you can argue that a lot of modern managerialism, people like Tom Peters and a lot of the other management theorists of the past thirty years, owe a great deal to Buckminster Fuller. The thing of our time, which we don’t quite see, is that no one imagines or thinks about the future. What we say about the future is that it’s unknown. And that means it’s frightening—so lets just manage what we’ve got, the here and now, the best we can, to prevent the darkness and the chaos of the future from overwhelming us. I do think managerialism is the dominant ideology of our time—a static conservatism. I would love to do a series about it, but it’s impossible because it’s like water that has penetrated everywhere. So it’s very difficult to pull it out and show it to people as “a thing.” But that static conservatism stops anyone imagining other, better, futures. So much science fiction is basically dystopian as well.

HUO: William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, cyberpunk…

AC: Yes, it is deeply conservative—again, individuals lost in a dark world. But there is one writer who I think does transcend that—I mean, I think this is where Alan Moore is a genius, because he actually takes that dystopianism and uses it to create alternative realities, where you do manage to think in a new way.

HUO: Many artists keep telling me how they’re very inspired by Alan Moore. He’s a total guru.

AC: They’re right. I think he’s a genius. Because he is obviously driven by this idea that you could do really complicated things, both in narrative and in what you’re saying, yet do them in a really entertaining pop way. I would never compare myself to him because he is a sort of god, but I mean it’s what I try and do—pop stuff, right? I do jokes. I use silly music. I have dancing animals, anything. But I try not to compromise in what I’m saying. I don’t simplify it. I mean, I simplify it, but I don’t degrade it. But he doesn’t, either. And the way he structures narrative is just incredible.

HUO:It’s also not a coincidence that many visual artists right now want to write a novel. And I think many of these artists are so fascinated by you because they actually see you as a novelist.

AC: You mustn’t try to grand up what I do too much. It is at heart journalism about power in the modern world—using film. But mood-wise I do try and take factual stuff and make it feel like a novel. It doesn’t mean it’s fiction. The facts are true, and I then erect an argument on top of that, but I always want it to have the feel you get from reading a novel, that draws you in emotionally. Some people say that the way I edit, it’s hypnotic, and you create mood. It’s like you would in a novel. Someone like Alan Moore will suddenly have a whole mood, and you can see exactly why he’s doing it—he’s emotionally placing it. That’s my great dream. It’s not only when it begins to fall into place and make sense. At the moment, I’m turning over in my mind how to make a film about what has happened to power in Britain over the past twenty years. There are obviously good stories—like how with what is called the “democratization of luxury” everyone has become their own little aristocrat—having weddings in stately homes and buying super-expensive handbags—the story of the rise of the handbag over the past 10 years is great and very funny. While at the same time the real rich elites have basically disappeared from view. I think they’ve all gone to live in Zug in Switzerland. But I do know to make something like that work—that you have to find a way of coming at the recent past in a way that makes people look at it fresh. And that is about giving the recent past a mood that people can feel. It’s not only about events that happened. It’s like when you go into an old building, it has a mood. It’s almost like you can smell it…

HUO: An atmosphere.

AC: An atmosphere, and the thing now is to try and find a way of making, I don’t know, a time in the recent past like say 1993, and giving it an atmosphere. It’s taking something that people feel they know very well factually and, without changing or distorting the facts, giving it a new and fresh emotional feel—both through the way you use archive, and the story you tell that takes you through it. So you make people look at that period again. For example with something like the Bosnian conflict—you want to find a way of showing it as something that was really experienced and that people lived through—not as the three or four shots that are always repeated in news items. Shots that in their constant re-showing have in a way become a concrete wall that stops people really looking at that extraordinary time.

HUO: That proves the theory right about Walter Benjamin, who says that the most exciting thing is not the past. The most exciting thing is not the future. The most exciting thing is not the present. The most exciting thing is the ‟just passed.” Are you working on the next film?

AC: Yes—and I am also going to be doing another live show—starting in Manchester and then going to New York. I want to try and show dramatically how power really works in the modern world—but in an entertaining way. It’s going to be with some very interesting collaborators, but I’m not allowed to talk about that.

HUO: One very last question: What would be your advice to a young filmmaker, journalist, novelist, artist?

AC: You mean, how can you create something that’s genuinely different? You look for the story that grabs your imagination and that feels different from anything else. That’s all. There’s nothing else. Then you’ve seen the future. You can try and copy what you’re supposed to do, which you should do, to begin with. But after that, everything is about making sense of the fragments. That’s how you see the future.