There is no vision without details.

—Hussein Barghouti

The psychic and geographical center of Ramallah is Al Manarah Square, a traffic roundabout where five streets converge at irregular angles. Cars and people circulate in apparent chaos around five carved lions statues—symbolizing Ramallah’s five prominent families—which encircle a single Corinthian column, as if standing guard. One lion wears a wristwatch, and depending on one’s sense of the ironic, this detail can be read today as a cryptic joke about the materialist slant evident in contemporary Palestinian society, or as a mordant commentary on the duration of its status as an occupied territory. During the Second Intifada, the story goes, some of the lions had their carved tails smashed off by Israeli soldiers—an action that can also be read doubly, a term of endearment for the fedayeen being achebals, “young lions,” while Palestinian slang for a collaborator is to say he or she has a “fat tail.” The West Bank is full of such polyvalent significations, an indication of how the conflict between Palestine and Israel is carried out at the level of semiosis as much as territoriality.

From Al Manarah, it is a five-minute walk up Ada’a Street to the building of the International Academy of Art Palestine (IAAP), a villa that once housed Gallery 79, a well-known art space shuttered by the IDF during the First Intifada, and in the ‘90s, offices of the Palestinian Authority (PA) Ministry of Culture. Although surrounded on two sides by pavement and concealed from the street by a nondescript office building, the villa retains a certain elegance. Its front entrance, surmounted by an uncovered patio, is lined by an iron balustrade, its portico flanked by twin columns with a hint of Arabesque filigree. It was there in 2010 that I first learned about Khaled Hourani’s idea of bringing a Picasso painting to Ramallah. I recall students saying it was to be exhibited there at the Academy. I recall being startled by the prospect. I may even have been told this while sitting in the IAAP’s single classroom, the room where, now subdivided, the Picasso hung for a month last summer.

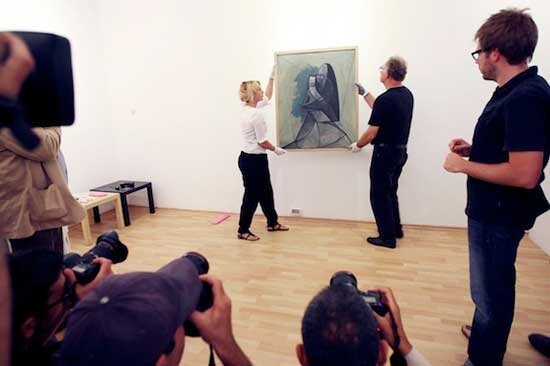

In all likelihood you’ve heard about the project—how Picasso’s 1943 portrait of his lover Françoise Gilot, Buste de Femme, was loaned to the Academy by the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. (A parallel exhibition at Al-Ma’mal Gallery in Jerusalem displayed correspondence culled from the paper trail left by the two-year effort to realize the work.) The story was widely reported: the German newspaper Die Zeit assigned two reporters to follow the project’s development, publishing a lengthy account two days before its gala opening; the Guardian, Al Arabia and Haaretz published accounts; wire services and online news agencies ran the story; television networks sent camera crews; and, of course, members of the art press weighed in—including Frieze magazine, which in its online edition published a detailed report on the opening festivities by Nick Aikens, an executive from Outset Contemporary Art Fund, underwriters of the two days of talks which followed the opening. The recently published twenty-second issue of the Belgian art magazine A Prior is dedicated to the project, as is a planned documentary by Rashid Masharawi.

Most of the news coverage subscribed to a fairly standard narrative and an equally predictable itinerary of facts. Though started on a whim, in the end, orchestrating the passage from Eindhoven to Ramallah of the most expensive work of art ever exhibited in the West Bank proved more complicated than raising the $200,000 necessary to fund the exhibition. Thousands of Palestinians flocked to see the painting on view, but despite extensive modifications to the Academy, the museological conditions were improvised at best. The central motive of the project—to canalize the sign-value of a work by Picasso, modernism’s most iconic artist, in the service of imagining what a normal institution of art in a normal state might look like—was clearly and repeatedly articulated; in a region where the news is unremittingly ugly, a “feel good” story is an infrequent occurrence; the law of scarcity demanded that the most be made of it.

Having neither seen the exhibit in person nor followed its development, reading these accounts was the starting point for my own attempt to grapple with the project and what it meant. It was, after all, a fairly simple proposition, being, as Van Abbemuseum director Charles Esche phrased it at the opening, “only strictly concerned with the shipment of a small amount of wood, canvas, and paint from one country to another.” Yet, as I pondered the news reports, something remained elusive. The constellation of journalistic details seemed to circulate without coming to rest anywhere. I grew interested in what this failure to adequately pin down a meaning outside of several safe, uplifting messages—a failure I felt in myself and saw reflected in the media—implied for the project itself and the context of which it was a part. “In the making of Picasso in Palestine,” wrote Rasha Salti and Khaled Hourani in their contribution to A Prior 22, “the means are as interesting as the end. The means are, in fact, an end in themselves.”1 In being reduced to a couple of paragraphs or a minute-long news report, these means would inevitably fail to be explicated, and consequently, the project’s most interesting aspect—employing the protocol of museum loan policy to unmask the administrative relationship between Israel and the West Bank—would remain largely untold. Spatial limitations would reduce this recondite topic to a thin trickle of information. Entrenched journalistic habits of depiction would do the rest—the real conditions of occupation that the project ostensibly intended to address would be pushed to the margins by that set of stock clichés which stand readily at hand for depicting life in the West Bank.

In speaking of our mental conception of space, the Marxist philosopher Henri Lefebvre describes two commonplace illusions—the “illusion of transparency,” which goes “hand in hand with a view of space as innocent, free of traps or secret places,” and the illusion of opacity, or “realistic” illusion, which is closer to naturalistic and mechanistic materialism. Rather than opposing one another, “each illusion embodies and nourishes the other,” reinforcing an idea of the world where no obstacle interferes with our ability to conceptualize it, and that “‘things’ have more of an existence than the ‘subject,’ his thought, and his desires.”2 Over the years I had come to suspect the successive Israeli governments of being masters at capitalizing on these twin habits of mind. Most of the press coverage, however, appeared indifferent to how these habits were unsettled by the project; as blind to the complexity of Buste de Femme’s actual journey as to its metaphysical dimension; incapable of seeing something—or to be more precise—sensing something underneath Picasso in Palestine’s ostensible goal of instantiating an encounter between a lone Picasso painting and the Palestinian public. Perhaps this something was a kind of immaterial non-event or non-thing, a form of administrative antimatter exerting influence while never becoming visible, maintaining control by remaining resolutely invisible. Or perhaps—more speculatively—it had to do with the transposition of an artifact of European modernism to another time and place in combination with the empty place of Israeli administrative control, the indeterminacy of modernist art production entering into uneasy orbit with Israeli occupation strategies, creating in a sense two empty places: the former marked by the refusal of pictorial realism (coherent representations of pictorial space, the suppression of surface incident) and the latter by the Israeli state’s particular way of exploiting a “democratic invention,” to borrow Slavoj Žižek’s term, that “consists in the very fact that what was previously considered an obstacle to the ‘normal functioning of power’ (… the gap between this place and the one who actually exerts power, the ultimate indeterminacy of power) now becomes its positive condition.”3

In attempting to address the many questions I saw unanswered in the press, I began conducting interviews, collecting news accounts on recent developments in the West Bank, and otherwise immersing myself in the story. But I soon encountered a limit to my understanding—a limit that also characterizes the effects of Israeli occupation in the West Bank. This limit, this “gray zone,” exists (to the extent it is even localizable) on a plane where the allegedly hard facts of Oslo over time have deteriorated into something capricious and arbitrary.

Even while granting this “Kafkaesque” gray zone pride of place, I was aware of another facet to the story. It concerned why, in the various methods of civil and military resistance employed by Palestinians, there exists a make-believe element, like the pantomimed game of cards Jean Genet turned into a central motif of Prisoner of Love, one of “the day-dreams people have to work off somehow when they’ve neither the strength nor the opportunity to make them come true.” I suspected Palestinians still possessed this proclivity, using it to toy with the threshold at which play-acting “stops being poetic negation and becomes political assertion.” In fact, the declaration coming immediately after this line precisely indicates the sort of temperament that could formulate the quixotic project of installing a Picasso painting in a tiny room at an art academy in Ramallah as a form of resistance: “If such imaginary activity is to be of any use, it has to exist.”4

1. The Ballad of Picasso and Palestine

Checkpoints, which litter the Palestinian landscape, speak to a central Palestinian predicament of a disordered experience of geography and space-time, whereby “Palestinian life is scattered, discontinuous, marked by the artificial and imposed arrangements of interrupted or confined space, by the dislocations and unsynchronized rhythms of disturbed time.”5

Where to begin the story of Picasso in Palestine? One can take the historical long view and say it began with the Zionist movement. One can take this view and from it elaborate a secondary, rhetorical dimension, pointing out that from its inception the language of Zionism extolled the benevolent, civilizing influence of European culture to justify colonization. One could also begin with the lengthy, non-controversial record of museum exchanges between Western and Israeli institutions, or, on a more abstract plane, from the assumption that Western culture and art have long been “in a ‘natural’ conversation with Israeli artists,” a characteristic noted by Khaled Hourani and Rasha Salti in their aforementioned essay.6 Seventy-five kilometers east, this same conversation is still considered “unnatural” and alien.

If we are to be more specific, our story begins in January 2009 when Khaled Hourani visited Eindhoven as part of an ongoing roundtable discussion organized by Charles Esche involving culture workers from states within the former Ottoman Empire. Esche, whom I spoke with last July, described these meetings as an attempt to explore ways of facilitating broader cultural exchange outside the cultural parameters of the Van Abbe’s Western European home. During this particular round, Esche’s guests were shown around the Van Abbe’s facilities—the administrative offices, the collection storehouses, the conservation workshops—while members of the museum staff explained loan policy, conservation, storage, and the other myriad tasks involved in maintaining a collection. Convening later in a conference room together with staff curators Galit Eilat and Remco de Blaaij, Esche posed a rhetorical question: What would the participants do if they had access to the Van Abbemuseum’s substantial collection of 2000 drawings and 700 paintings, including works by Lissitzky, Kandinsky, Chagall, Beuys, and Pablo Picasso? Hourani answered, saying he would choose to “bring one of your Picassos to Ramallah.” His response was met, wrote Gareis and Salewski in Die Zeit, with mirth and incredulity; Esche replied, “You cannot bring Picasso to Palestine. How will that work?”

Confirming this exchange, Esche recounted the story like this: “Basically, quite spontaneously, this idea arose. It did come up as a wild idea. And then it was laughed [at], dismissed—‘Oh yeah, that would be amazing’—but not really taken seriously.”

Although initially made in jest, Hourani was immediately struck by how such a loan would inscribe Palestine within the administrative procedures of a prominent Western museum in an unprecedented manner. For several weeks, he did not speak openly about his idea. “I was not able to talk about it directly,” he said, “because I know it will blow with the wind if I did not do my own thinking and research how to make this happen without this being silly or about laughing and only making jokes.” When he finally chose to speak, Hourani began a cautious campaign of persuasion, initiating a dialogue with Charles Esche (facilitated by a meeting the group held in Istanbul some months later) and another with the board of directors of the IAAP, where Hourani serves as artistic director. Esche was at first skeptical. “I think skepticism isn’t wrong,” he told me. “It wasn’t a thing I embraced, like, ‘Oh fabulous,’ you know? There was a sort of questioning of what it would mean to take a Picasso from this Western European culture and show it in Palestine. Is it a form of cultural imperialism? Is it a colonialist form of educating the natives, if you like, to describe it in the crudest way possible? What would it mean for us to do that? Particularly, what would it mean for us to do that in terms of the message we’re sending about an institution that no longer assumes it knows its way in the world.”

Around the same time as Hourani began conversing with Esche and his staff, he convened the Academy’s students in its sole classroom, where, as a sort of game, he reviewed the Van Abbe’s collection in a PDF presentation, asking them to pick a work to bring to Ramallah. Although the possibility of the students choosing a contemporary work had entered his mind, one can surmise Hourani was already intent on steering the choice towards Picasso: as a prelude to this exercise, Hourani had conducted a rudimentary sociological survey, finding that in Palestine, as in many other countries, the name “Picasso” is commonly bequeathed upon artistically precocious children. Hourani recalled the discussion like this: “I was thinking, for example, that they might choose a contemporary artwork—a video or an installation, whatever—but we began talking about modernity, about how we could use or revisit modernity somewhere else, in a contemporary art practice.”

Of the three Picasso’s in the Van Abbemuseum’s collection, Buste de Femme (inventory number 387) was chosen. “There was one more painting from Picasso, also a portrait of a woman, from 1912,” Hourani related. “There was like a competition between the two works. But Buste de Femme—as a work from wartime—was more representative of Picasso than the one from 1912 … The idea was not to bring a political artwork from Picasso, like a direct political work. To bring a portrait of a woman, it will open the discussion of the woman in art in general, and the history of representing the woman in Palestinian art, since it has been represented in different ways, as a symbol for the homeland, nationality, identity, and so forth. It has a lot of history.”

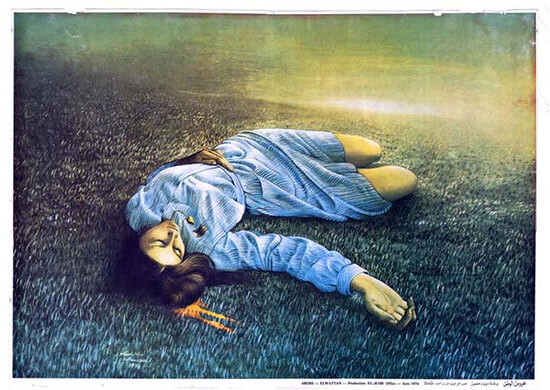

2. The Buste de Femme Enters Dressed as Lina Nabulsi

From the start, Picasso in Palestine was intended to do more than simply introduce Picasso to the Palestinian public. The painting would not only have the destination of Ramallah listed in its provenance, it would also enter into a process of semiotic slippage, finding itself inscribed with an alternative set of interpretations and associations. By mentioning the history of female representation in Palestine, Hourani is alluding in particular to depictions of the female form in post-Nakba political graphics and fine art, where, frequently in a gravid state, she signified the Nation, Palestinian identity and culture, and Sumud (meaning steadfastness or perseverance), the term for a set of techniques of passive resistance that came into practice following the ouster of the Jordanians in 1967. The logic behind this move is not unique, association and iteration being established parts of the Palestinian historical discourse. Discussing the PLO insurgency of 1968-71, a Palestinian friend once commented that in order to understand the enduring effect of its failure, you had to return to the Arab Revolt of 1937. Similarly, to understand the ‘67 War, you have to go back to ’48, while comprehending Baruch Goldstein’s 1994 massacre of twenty-nine Muslim worshippers at the Cave of the Patriarchs requires returning to the 1929 Arab massacre in Hebron, or, for a second level of retributive motivation, to the biblical story of Purim itself, which involves a foiled plot by a courtier of the Persian king Ahasuerus to exterminate the Jews in his Empire. Buste de Femme is especially in dialogue with Sliman Mansour’s famous painting Bride of the Homeland, which portrays the death of Lina Nabulsi, a Nablus schoolgirl killed by Israeli Soldiers in 1976 during a school protest.7 Such was the potency of this image that when a lithographic edition began to be distributed, the Israeli intelligence service immediately seized the remaining posters and the original painting as well. The comparison of Buste de Femme to Bride of the Homeland is emblematic of the type of reappraisal that would occur if Picasso’s painting were introduced into a new constellation of references, a détournement of significations that the organizers hoped would be reciprocal—affecting both painting and context alike.

3. “…to go as far as we can”

Despite Esche’s reservations, throughout the summer he and Hourani continued their “critical analysis” of the project. Esche was eventually won over by Hourani’s determination. The IAAP posted an official loan request in August 2009, providing assurances that “the Academy realizes full responsibility for adequate exhibition conditions and guaranteeing the safe return to the collection of the Van Abbemuseum.” The letter, delivered to the museum’s library, was duly stamped and filed, with copies distributed to Esche and director of collections, Christiane Berndes. According to Die Zeit, when Berndes read the letter, she immediately phoned Esche, shouting into the receiver so loudly he had to hold the phone away from his ear.8 Esche laughed at the memory. “Of course, the first thing she said was, ‘You can’t do that! There isn’t a museum, there aren’t the conditions, there isn’t insurance. It’s ridiculous. It’s the property of the citizens of Eindhoven, you can’t just throw it away, you know?’” Berndes might have mentioned very specific worries: the dilapidated state of the West Bank’s roadways, the many opportunities for calamity to occur upon them—especially at Israeli checkpoints—not to mention the lack of a facility with anything like the temperature control necessary for exhibiting a fragile artwork that only recently had been restored at no small cost.

Esche placated Berndes’s concerns by turning the loan into a hypothesis: “We started talking about it, and I said, ‘OK, this is true, but nevertheless let’s see how far we can go down this line as perhaps a paper exercise, perhaps something that at the end of the process of discovering whether we can do it, we can’t do it. But let’s make an effort to go as far as we can.’”

Remco de Blaaij, who would soon become the Van Abbe’s point man for the project, recalls Berndes reluctance this way:

I think Charles was kind of subtle in preparing Christiane for the questions that would come out of it. And of course, Christiane has a very clear mandate in terms of being director of the collection, and that is to protect it from damage—and I’m also talking about weather and stuff like this. It’s a very straightforward, practical matter, but very related to the protection of icons and the protection of heritage, I would say. So, the questions that were holding her back, I think these were gradually shifted by Charles and also by Khaled’s visits to Eindhoven. Whereas she first thought it was kind of a threat, slowly, she saw the potential. Charles, me, and all the other people in the project saw it as having potential, but we were a bit less aware of other scenarios in Christiane’s head. She worked with us to explain much more about the way she was working in the museum and all these kind of things.

Having overcome Berndes initial reservations, Esche posted a letter in November, agreeing to explore the myriad “chain of problems” involved in sending a Picasso to Ramallah. It is difficult to establish a direct causal chain between Hourani’s request and Esche’s own aspirations for refunctioning the Van Abbe’s lending procedures, but the fact remains that even before the IAAP delivered its request, he was already in the process of developing an “active lending policy.”9 According to Esche, the lending policy up to approximately 2009 was entirely passive. When a letter or email requesting a loan arrived, the museum would respond, and ordinarily, these requests came from institutions with which the Van Abbe was already familiar. What Esche envisioned was a dynamic approach to the collection, seeking out new, unconventional exhibition situations and building a network of institutions, since “obviously, the difficulty with a passive lending policy is you basically lend to the people you already lend to or that fulfill all the conditions of the art system, which means you never break out of a very staid, bourgeois model of exhibition.”

The Picasso exhibition would be a test case to see what challenges awaited a departure from this model. In fact, this apparently simple proposition entailed striking out into territory where the map possessed was vague and imperfectly understood. As Hourani phrased it: “It was clear from the beginning that this project would revisit and question all the political agreements, all the bureaucratic systems, all these things that are not necessary. All these details were for us to learn.”

4. The ABCs of Administration, or, How to Pretend You’re not Occupying a Territory

It is not my intention to enter into a disquisition on Israel’s current policy of occupation, except to say that it is mutable. At the moment, it is based both on aggressive support for settlement efforts and a deliberate attempt to lighten some of the more obvious burdens of occupation, such as roadblocks, while other burdens, like housing demolitions and the restrictions on building in Area C, have become increasingly onerous. The area of occupation that directly affected the Picasso project—laws governing imports and exports—have been liberalized to a certain degree, but the threat of a Gaza-style blockade is always a remote possibility. Goods may enter the West Bank with relative ease (exiting is a slightly more complicated story), but this surface normalcy in the sphere of economy is in itself deceptive. It is worth looking for a moment at how Israel has exploited the terms of the Oslo Agreement to create a situation of managed instability, for it is in the fiscal sphere where the PA is most straightened. Foreign aid still comprises the lion’s share of the PA’s operating budget, but the Israeli Civil Administration holds responsibility for disbursing tax receipts from imports, exports, and other sources. They have often used this duty as a means of expressing displeasure. Thus, Palestine often finds itself on the receiving end of an economic vise, as was the case in 2006 after the victory of Hamas in legislative elections, when Israel halted transfer of $55 million in tax receipts, or more recently, when a similar move followed the announcement of Egypt’s sponsorship of reconciliation talks between Fatah and Hamas. Far from negligible, this sum makes up a third of the PA’s operating budget, paying the wages of 160,000 Palestinian civil servants (among them 60,000 security and police officers), on which, in turn, a third of Palestine’s population depends.

Predictably, the PA’s decision to unilaterally seek a vote on statehood at the UN elicited a litany of threats directed at its pocketbook, not only from Israel but from North American and European donors as well. The latter also resort from time to time to threats of withholding aid, but are usually more hesitant than Israel to make good on their threats. This time their fulminations had a ring of authenticity lacking in previous oaths.10

Whatever else it does, considered as a psychic force, Israel’s occupation improvises upon a motif suggested by the contingency of current events to keep Palestinians in a state of perpetual discomfiture. I first started to comprehend, if imperfectly, how this ambiguous legal framework operates—that is, through a comprehensive set of legal codes on the one hand and a complete lack of clarity on the other—while working with DAAR (Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency Program) in the summer of 2010. Their project involved the borderline between Area B and Area C—two of the three zones mandated under Oslo that have carved the territory of the West Bank into a patchwork of discontinuous jurisdictional islands.11 The project concerned a villa built on the borderline between Area B—under PA control (meaning control not only of security but also zoning ordinances, building permits, and so forth)—and Area C, under the control of Israeli security forces, where construction by Palestinians is forbidden without a permit from the IDF, which, as a rule, is never granted. A settler organization, Regavim, had filed multiple petitions in the Israeli Supreme Court against the villa on account of this supposed breach.12 To an outsider, the case appeared easily resolved merely by consulting the Oslo map to determine if the villa fell within Area C. Except this is the West Bank, where surface appearance is only one facet of reality. The map possessed by the Battir municipality (in which the villa is located) showed the line in one position, while the PA copy placed the line elsewhere. The line itself, claimed Alessandro Petti of DAAR, had a volume ranging between five and ten meters in width, with the result that either most of the house or only a small fraction could be interpreted as lying inside or outside Area C. In the end, this detail mattered little, as the Israel Supreme Court had thrown out both of Regavim’s lawsuits (a fact relevant only because the owner of the villa had the wherewithal to hire a lawyer and the determination not to be harassed by a settler organization, whereas in other situations, buildings have been torn down on a similar pretext).13

I could not understand what was going on. My incomprehension led me to Shaul Arieli, a former IDF colonel responsible under the government of Ehud Barak for drawing up the Oslo map. In his office at the Economic Cooperation Foundation in Tel Aviv, Arieli assured me that since the Oslo map was plotted digitally by the Israeli Cartographic Institute, the borders between A, B, and C had no volume. The Israelis, he said, wishing to avoid at all costs precisely these sorts of jurisdictional disputes, had distributed multiple copies of the map to the nascent PA. I wanted very much to believe him, but I didn’t quite. More than that, I wanted to believe in the existence, somewhere, of objective facts that could be appealed to in situations such as these: I was reluctant to concede their absence. Arieli’s asseverations to the contrary failed to reassure me.

5. The Back Story of the Back Story

While the ground was being laid for the Picasso in Palestine exhibition, Hourani was at work on another project. Produced for the 2009 Jerusalem Show (an annual event organized by Al Mamal Gallery in East Jerusalem), Jerusalem 0.0km consists of eighty handcrafted ceramic plaques distributed in towns and cities across the West Bank, Gaza, and outside the Middle East, listing the distance from the point of installation to Jerusalem (including a marker embedded in a wall adjacent to the bookstore of the Van Abbemuseum). At the ceremony commemorating the installation of the marker in Ramallah, Hourani spoke with PA Prime Minister Salam Fayyad, making arrangements to meet later in his office. There, according to Gareis and Salewski, Fayyad enthusiastically endorsed the project, offering to provide whatever logistical help was required. Which was considerable, says Hourani: “We had a logistic need. We needed a letter from the government to be written to the insurance company and the museum guaranteeing the safety of the artwork, of the $7 million artwork during the time when it’s in Area A. It had to be under the responsibility of the government.”

That Hourani could have such ready access to the PA requires further explanation. In fact, his background is crucial to understanding both his ready access to the PA as well as the project’s objectives. Born in Hebron to a large family, Hourani is no stranger to politics or politicians; among his twenty-one siblings, several have been politically active. His brother Muhammad currently represents Hebron on the National Council. After starting as a fairly conventional painter and sculptor, Hourani has moved progressively towards curatorial and interventionist work in the vein of third-generation institutional critique artists such as Jens Haaning and Maria Eichhorn. But like many Palestinian academics, intellectuals, and culture workers, his professional activities—out of necessity or a natural bent for eclecticism or a combination thereof—encompass many fields and are inflected by political ideology and party affiliation in a manner seldom seen today in the West. He has written plays, curated exhibitions, and worked as a consultant and in advertising. His CV, replete with directorships and board memberships, indicates a man accustomed to maneuvering inside the machinery of power: besides his current post at the IAAP, where he can typically be found ensconced in his office, wreathed in a haze of cigarette smoke, he has previously held positions at the Palestinian Association for Contemporary Art, the Palestinian Artist League, Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center, as well as his lengthy tenure as Director of the Plastic Arts at the Palestinian Ministry of Culture.

In Hourani’s case, his local prominence has its roots partially in his political activism. “Khaled’s Fatah, you know that, right?” So said Samar Martha, a Ramallah-based curator and Hourani’s former colleague at the Ministry of Culture, when we spoke. “His family comes from a Fatah background. His father has been political—I think he was in jail a couple of times during the occupation. Khaled was in jail, I think, during the First Intifada; his brother Wafa was in jail. Muhammad was in jail. Most of them were quite active in the First and Second Intifada, so he’s very much endorsing the PA as a structure and the way it functions.”14

6. Finding the Right Channel

When Fatima AbdulKarim, who joined the project late in the fall after quitting her job at the PA Ministry of Foreign Relations, began working full time on Picasso in Palestine in the spring of 2010, the project had encountered its first setback. The in-house insurance broker for the Van Abbe, AEK, refused to consider the loan.15 AEK recommended another agent to Esche, Ruud Ijmker, a veteran manager at the Dutch firm SNS REAAL (which insures, among other things, the Majorcan tuna fleet). Ijmker, who possesses a certain notoriety in Dutch insurance circles (he is quoted in Die Zeit as saying, “Anyone can insure normal stuff, I’m the crazy one who goes for the extraordinary things”), was intrigued by the project. In April 2010, Ijmker was in Israel on separate business when Eyjafjallajökul, the Icelandic volcano, erupted, stranding him for several days. He used this unexpected turn of events to visit the IAAP and begin investigating the project’s potential insurance liabilities in greater detail.

At the Academy, Ijmker photographed the locks on the doors where it was proposed the painting be exhibited, examined where security cameras should be mounted, where armed guards should stand. He drove to Jerusalem counting potholes and bumps. He encountered a snag when the question of national jurisdiction surfaced, since there is no real indication in the Oslo Agreement of what procedures govern jurisdiction and liability in the case of cultural exchange. But Ijmker, choosing to disregard Oslo in his calculations, concluded that the risk was insurable, writing a policy covering the painting’s travels “from nail to nail.” (AbdulKarim was quoted in Al Jazeera saying Ijmker decided simply to “erase Oslo from his mind.”)

Following closely on Ijmker’s heels were Van Abbe Chief Conservator Louis Balthussen and Registrar Bettine Verkuijlen, who, between 2010 and 2011, made several trips to the region, examining the condition of the Academy and West Bank roadways in order to construct a careful plan for how to protect the painting against possible damage. This included inspecting, as Ijmker had, the roadways, the layout of the IAAP, and learning as much as possible about what sorts of contingencies might await the painting at Qalandiya Checkpoint. Balthussen hit on the solution of designing a crate fitted with shock absorbers to mitigate the bad road conditions, and as an added step, placing the painting within a second, transparent travel container that would further stabilize temperature but also act as a barrier should a soldier on duty insist on opening the travel crate, which was always a possibility. That way, at least, the Buste de Femme would be protected from the dust of a Middle Eastern roadway. Bathussen extended this idea to his concept for the exhibition space, designing a room-within-a-room that would help the temperature and humidity remain stable.

The work of Balthussen and Verkuijlen, once they saw for themselves the conditions they would have to guard against to keep the painting safe, and Ijmker’s own difficulties in determining what to do about the Oslo Agreement, were easier solved than the organizers’s negotiation of the legal morass the project had created. “One of the considerations we had is that there was no way the Picasso would be entering without a diplomatic status,” said AbdulKarim. “This is the most sensitive thing that the press never got right, by the way. The painting needed to be cared for and transferred as: 1) a diplomatic package; and 2) a fragile, important Picasso art piece, etc. If it wasn’t the two together, it would have been impossible.”

Transporting Buste de Femme as a diplomatic package might safeguard the painting physically, and it would also solve another equally pressing issue. Since the IAAP is not recognized internationally as a museum, not only was it difficult to receive the customary assurances that the container’s integrity would be respected, but crucially, the IAAP would be liable for the 16% import duty Israel would levy on the painting’s value, appraised at €5 million according to Die Zeit, as one condition of the insurance policy. This figure was beyond the reach of either the Van Abbe or the Academy.16

An international agreement governing the tax exemption of museums has been in place for many years. At one point the IAAP attempted to apply for this agreement. They were not accepted. Without this agreement, the IAAP would have to look for another mechanism to avoid the import duty, since any country would require such an import duty if the borrower were not a registered museum. As Remco de Blaaij explained,

Of course, the Academy is not recognized by this international agreement. This is the point. Secondly, how to deal with taxes in a country that legally does not exist. This is a problem. So then you see for all kinds of tax reasons you’re dealing not with the Palestinian territories, you’re dealing with Israel. And as the Academy is not an internationally recognized museum … well, it was a big problem for us. It was kind of a large sum that had to be paid, or had to be arranged, as a deposit and you would not be able to touch the funds for six months.

Let me be clear on one point: if Munib al-Masri, the Palestinian Rothschild, had chosen to use some of his considerable wealth to underwrite an exhibition of the Mona Lisa in Nablus, there is little Israel’s custom’s office could do to avert such a spectacle. There is nothing illegal about loaning a painting and exhibiting it in Ramallah or elsewhere in the West Bank. The problems arose with the necessity of both the IAAP and the Van Abbe finding a way to secure a tax exemption; ultimately, all attempts to resolve the tax exemption of the painting would be accepted or rejected by Israel.

Hourani and AbdulKarim began approaching embassies. According to AbdulKarim, the Dutch consulate refused to participate, issuing a response to the Van Abbe stating it was not within the “regulations and norms” of what could be sent under diplomatic cover, since it was not a governmental project. Because the project was a Low Countries issue, the French, German, Belgian, and Spanish consulates all declined to help. UNESCO agreed to help, but the Israeli Customs Office rejected their letter.

By then, it was apparent to the team in Ramallah that its reading of the laws governing Palestine/Israel trade were insufficient. “This is a reflection of a general theme,” AbdulKarim elaborated. “Palestinians do not understand [that] Israel is not taking up all of its duties, and part of it is we don’t know what these are because the translations governing the various laws were slightly different.” Since the legal codes the team was consulting also stated that municipalities were tax exempt if they used the tax code of the government, Hourani and AbdulKarim approached Ramallah municipality. That didn’t work, according to AbdulKarim, because the municipality had always received its imports under the name of the sender.

7. A Curious Incident

The initial exhibition date of October 2010 came and went, as did a second date proposed for spring 2011, scotched on account of the Arab Spring. The team rescheduled for the summer of 2011, considered by Hourani a final deadline, since no one could predict what would follow the UN’s anticipated vote on Palestinian statehood slated for the following September. “It was a very critical moment in the last months,” said Hourani. “Everything is connected in this region, and a lot of heavy political things were happening around that might affect the project. I was happy with the revolution in Egypt. As a human being, I was happy. But at the same time, I was afraid. I was a bit worried about the project. I was selfish. I didn’t want things to be upside down, to destroy everything. We were fighting to get the work on time. The project would not be possible in a year from now. This was the critical time.”

Late in May, AbdulKarim secured a tax exemption number recognized by the Israeli tax and customs department (according to de Blaaij, this number was used in negotiations but not to transport the painting).17 Still, with only a week to go before the Buste de Femme’s scheduled departure, the sort of protection the painting would travel under remained unresolved. Sending it as a diplomatic package had failed, as had officially registering the IAAP as a museum. Using either the tax exemption number of the PA or Ramallah municipality had both come to naught. The only option left was to have Buste de Femme travel under the ATA Carnet and TIR Carnet treaties. Throughout the whole process of figuring out how to move the painting, several Israeli and Dutch art transporters—along with Samer Kawesmi (whose exploits in the accounts of many of those involved assume near mythic status)—had consulted with the Van Abbe and the team in Ramallah. Now Kawesmi, together with Globus and Kortmann—the two companies who had been awarded the contract from the IAAP to handle the painting—examined these treaties anew, having previously dismissed them as unsuitable.

An ATA Carnet (Carnet de Passage en Douane pour l’admission temporaire) is a customs document allowing the operator to temporarily import or export goods to countries acceding to the convention without paying duties or other levies, provided that the goods are reimported into the country of origin by a certain date. The TIR Carnet is a UN treaty that allows for the harmonizing of customs regulations for goods transported in sealed vehicles or containers. Outside of diplomatic immunity, TIR authorization was the only thing stopping a highly motivated Israeli soldier stationed at either of the two checkpoints between Ben Gurion Airport and the West Bank from insisting the specially constructed travel crate be opened, exposing Buste de Femme to the potentially disastrous heat of a Middle Eastern roadway.

While Israel is a signatory to both treaties, Palestine, as a non-state, is a signatory to no international agreements. As AbdulKarim discovered, Palestine is covered by all international treaties to which Israel is a signatory. Here arose a conceptual difficulty: to state Israel as the destination of the painting perverted the project’s entire concept. A struggle ensued over naming Israel as the destination country, but the conceptual barricade the team had approached proved impassable. “It was clear,” said AbdulKarim. “We have no airport, we have no borders whatsoever, and it needed to come through Israeli controlled borders.”

Responsibility for granting the ATA and TIR lay with the Dutch Chamber of Commerce at Hoofddorp (the town closest to Schiphol Airport). For reasons of their own, they were at first skeptical that Palestine was the country of destination, and demanded additional documentation. In the end, an unknown combination of pressures convinced the officials in Hoofddorp to authorize the TIR. But for AbdulKarim, something in this confusion remains unpalatable:

There was a request by the Dutch Chamber of Commerce that we get a letter from the Israelis [saying] that they know it is not coming to Israel but to Palestine. And this sounded very weird at that point. Very, very weird. I still can’t explain it. This is one of the things I would still like to return to from this project. We got the letter. I signed the power of attorney for the Globus team members to do all that was necessary. We sent it off, and Samer and Globus made things happen in their way.

It wasn’t necessary at all, I would say. The documents came from an Israeli company that said “proxy company,” the proxy country was Israel and the end destination was Palestine, and the declaration of purpose clearly stated that it is in an exhibition taking place at the Academy, which is in Ramallah, not in Tel Aviv, etc. To me, that was really an unreasonable suggestion at that point, but something made them feel uncomfortable. So, I don’t know. I really cannot explain it.

Charles Esche was more sanguine about the issue:

As far as I can see, the guy who I spoke to a couple of times changed his mind at a certain point from being—I wouldn’t say obstructionist, but very bureaucratic, very precisely bureaucratic. He suddenly became helpful. It didn’t help that he googled the project, and at that time the number one hit was a comment from a hardcore Zionist website saying how this project was once again showing the Israeli government in a bad light.18 He came across that link and he said, “So this is purely a propaganda thing?” And I said, “No it’s not. This is a genuine loan that we’re doing, I can’t be held responsible for every opinion on the Internet about it.”

Clearly, going to Palestine is an issue. And certainly one of the difficulties is that Palestine doesn’t exist. I mean, it’s not Israeli territory, it isn’t Jordanian anymore, it’s not Lebanese, it’s not Egyptian. So what is it? If you’re trying to ship something to a place that obviously exists physically but doesn’t have a clear identity in this world that is divided into these clear identities called nation-states, then for the bureaucracy, that’s difficult. There are developments in the Netherlands that are approaching fascism in ideology, but I don’t think the Chamber of Commerce in Hoofddorp is part of that.

While one can attribute some of the reasoning in AbdulKarim and Esche’s statements to differences in their respective positions within the project, something else in this last minute chain of events remains absent in both accounts. A comment made by de Blaaij is perhaps the most telling concerning what kind of decision-making processes lay behind the final permission for Buste de Femme to travel to Ramallah:

There was indeed a gray area that was constantly flashing in front of our eyes.19 I think, in the end, it was a combination of having the Ministry of Finance tax number, together with some diplomatic pressure, together with negotiations between the transport company and the Israeli authorities that control goods coming in and out of the West Bank. I think, adding up all these small parts, this led to the final acceptance of the painting going through. And I think in itself it’s already gray, because it’s not saying, OK, we have this number here, we do it the completely legal way as it’s supposed to be, so it’s all fine. It’s indeed a whole gray area.

But also again, you see how these things are built up. You see how gray the supposedly white Oslo Agreement can be. The Oslo agreements are supposedly very clear for everybody, for the two parties, but if you see the reality on the ground, you see that it’s nothing more than gray areas all the time, functioning by creating gray chaos. It’s kind of a controlled and regulated chaos. It’s weird to see this from very close, because in the end decisions come down to administrative and bureaucratic practicalities, but in these practicalities, so much politics is embedded, I would say, and this is something we were confronted by a lot, especially when we wanted to do this as legally as possible, with the tax number and all that kind of stuff.

It is also so weird that when it comes down to seriously getting things done, nothing will be written on paper. As soon as you have something on paper, then you have evidence. So, a lot of the negotiations were by phone. The most serious stuff is in nobody’s emails, no paper trail, it’s really only on the phone. And I think this also tells you something about the politics embedded in bureaucracy, right? It’s a very clear signal that you’re entering either gray or black territory, because then there’s no way to produce evidence that you have an agreement with somebody.

In the end, the man from the Dutch Chamber of Commerce signed the TIR and ATA Carnet forms. Despite these documents, the crate was opened by a customs official at Ben Gurion airport for three minutes (a duration found acceptable by chief conservator Louis Baltussen) before being gingerly placed in a waiting VW Transporter. When the van reached Qalandiya Checkpoint, the Israeli driver was replaced by a Palestinian (one holding a Jerusalem ID enabling the holder to cross freely across the checkpoints dividing East Jerusalem from the West Bank). The soldier on duty ignored the customs forms, giving only a cursory look at the box before waving the van through. The precaution of arranging for a media scrum to be on hand to document the van’s negotiation of the three-kilometer no-man’s land between Qalandiya Checkpoint and Area A where awaited a PA security detail proved unnecessary—although this improvised element was essential to the insurance agreement, which stipulated the painting be protected throughout its journey from Eindhoven to Ramallah.20 There were no incidents then, or later on the road to Ramallah.

Rasha Salti and Khaled Hourani, “Occupational Hazards of Modern Art and Museums,” A Prior 22 (2011): 42.

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1991), 29-30.

Slavoj Žižek, “Class Struggle or Postmodernism,” in Contingency, Hegemony, Universality, Judith Butler, Ernesto Laclau, and Slavoj Žižek (London and New York: Verso Books, 2000), 93.

Jean Genet, Prisoner of Love, trans. Barbara Bray (New York: New York Review Books, 1986), 119.

Helga Tawil-Souri quoting Edward Said in Jerusalem Quarterly. See →.

Rasha Salti and Khaled Hourani, ibid., 46.

When the crate in which Buste de Femme had traveled was opened forty-eight hours after first arriving in Ramallah (to give the painting time to acclimatize), Hourani insisted Sliman Mansour, whom he described to me as the “hero of using the woman as a symbol in Palestinian art,” be on hand to witness this historic occasion.

Considering the layout of the Van Abbe’s offices, it is more likely Berndes would have gotten up and walked the four meters to where Esche customarily sits, unless, of course, he happened to be out of town when Berndes received the letter, which is more than likely the case.

To date, Picasso in Palestine is the only project to be successfully realized under the new lending policy, although Charles Esche told me there are two other projects currently in the works—a long-term project with SALT in Istanbul and a collaboration with a Chinese artist who wants to arrange an exhibition in his home village in Hunan Province.

See Ethan Bronner’s article “Before a Diplomatic Showdown, a Budget Crisis” in the July 27, 2011 edition of the New York Times →.

Those interested in how Israel uses zoning ordinances to restrict economic activity in the West Bank would be well advised to consult the Israeli NGO BIMKOM’s report on the matter, “The Prohibited Zone: Israeli planning policy in the Palestinian villages in Area C,” available as a PDF at →.

Regavim’s complaint about the villa was also part of a concerted effort to clog Israeli courts with lawsuits to combat state-mandated settlement building freezes on the judicial level and to garner political support within Israel for settlement as a political/demographic project.

Petti also alleged to have heard that the PA possessed only a single second-generation copy of the map, the others having been destroyed in the assault on Yasser Arafat’s offices during the Second Intifada.

In my experience, to say someone is “Fatah” connotes something specific, but not a specificity readily comprehensible to an outsider. Prior to Oslo it indicated (broadly) loyalty to Yasser Arafat and the PLO and a brand of Palestinian nationalism possessing neither the religiosity of Hamas nor the socialist orientation of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. But this distinction is not altogether helpful; both left- and right-leaning factions exist in Fatah, and neither camp corresponds exactly with similar political orientations in the West. Similarly, multiple splits have occurred following Arafat’s death: between leaders of the old guard, who returned from exile and came to power after Oslo, and Marwhan Barghouti, who, although imprisoned for life, initiated the Al-Mustaqbal Party (which in 2006 ran a slate of younger candidates), and also between different factions of this “Young Guard” which is itself prone to schisms. Thus, a Fatah loyalist, while actively committed to resisting the occupation and fighting for the nationalist cause, might be politically progressive, or he might be entirely comfortable with Palestine’s traditional class society in which a small group of clans based in the cities and towns controlled much of the region’s wealth and political power. (The function of clan power might conceptually be fairly opaque in the West. One might think of the Kennedy’s family as roughly homologous, although this analogy does not take into account that Palestine’s social structure predates that of Hyannisport by over a millennium, and may, accordingly, be more intricate in structure.) Being “Fatah” is also not a uniform designation. It can indicate rank-and-file party activists, armed members of the al-Aqsa Martys’ Brigade (who, while remaining identified as the armed wing of Fatah, have maintained in recent years a somewhat shadowy existence, having been sidelined by the emergence of the PA’s security forces and a somewhat contentious amnesty agreement reached with Israel in 2007), or that elite group of families—often headed by politicians or academics—who returned from exile with Arafat in the ‘90s, and who have since reaped many of Oslo’s political and economic spoils. In the past, this has been one of civil society’s chief complaints with the PA, but following Arafat’s death and the resulting political vacuum, the fragmentation of political power has assumed a complexity that would require more space than this footnote allows. Suffice to say, after Fatah’s 2006 electoral defeat in the Legislative Council, power was assumed by a non-Fatah technocrat, Salam Fayyad, who is now seeing his tenure draw to a close in an atmosphere of general rancor. It could be argued, equally, that following the assumption of power by a technocratic elite, corruption and overt party patronage has diminished, or the opposite, that today’s PA is no less corrupt than its ‘90s incarnation. What is apparent is that the power held by an economic elite has increased, and that in various ways, this increase is connected to political parties.

AEK is an Amsterdam-based brokerage, research, and corporate finance company. It’s website states, “AEK Brokerage services consist of institutional sales, liquidity providing, and facilitating the ‘incourante markt.’”

In the Die Zeit article, Galit Eilat is portrayed as having the unenviable role of the heavy—first as the Israeli national who some of the Middle Eastern visitors to Charles Esche’s rotating roundtable discussion were reluctant to sit with, and then as the deliverer of bad news about the Academy’s lack of status as a museum; AbdulKarim is thus set up as the plucky Palestinian culture worker who perseveres despite Eilat’s pessimism.

According to AbdulKarim, the issue of tax liability was in itself irrelevant, since the Palestinian Ministry of Finance was ultimately responsible for enforcing the tax or not. This is what she related during our interview: “During my three hours at the Palestinian customs department, we discovered that paintings are tax exempted, and not even the staff members themselves knew this. They started looking and looking until they found out. It was illegal in the first place for the Israelis to ask for the money, but this is the benefit of the doubt for the Israelis that hope its coming through our borders. But there was a big discussion going on between Sabah Nabulsi, the lady I was working with at the customs department in Palestine, and her Israeli counterpart, [with Nabulsi] saying, ‘No, this is coming to Palestinian territories, it’s end destination is Palestinian, therefore, the tax money is requested by us, not you.’ And they [the PA tax authority] were ready to overlook that.”

Esche is referring to a posting on the Zionist blog Israel Matzav from February 22, 2011, in which “Carl in Jerusalem” wrote: “Picasso in Palestine another occasion to bash Israel. Eindhoven’s Van Abbe Museum (sic) is lending the 1943 canvas Buste de Femme to the Ramallah international art academy, and the occasion is being used to bash Israel (original emphasis) once again. A film is due to be made of the painting’s journey, including the Israeli border and other checkpoints. And then international audiences will be shown how the “cruel Israelis” insist on inspecting an “innocent painting.” This is just another excuse to try to open the checkpoints so that weapons can be smuggled in. What could go wrong?”

Curiously, Van Abbe curator Galit Eilat also uses the term “gray zone” in her response to a question on the use of art in promoting tolerance in a conversation between herself and Zmijewski published in the issue of A Prior (#22) mentioned previously. Her notion of the potential political efficacy of art practice indicates a possibly homology between artistic constructions and the ambiguity of state functions described by de Blaaij. The pertinent passage reads: “Since art is considered autonomous, you can take even violent actions without being immediately labeled an enemy of the society. It still gives me a kind of gray zone to act in. This zone is never fully defined in political terms, that’s why it can accommodate change and be used as a tool for transforming the society.”

Another point where the official record is unclear involves precisely this question of how long Buste de Femme was left unguarded. In July, Hourani told me the following: “One of the scenarios was the Dutch transport company, Kortmann, would bring the work to Tel Aviv. From there, there would be an Israeli company – Globus – with security guards. They also have special security guards – not necessarily the government or the official police – like we also have some private security companies. Globus took care of the security of the work from there to Qalandiya Checkpoint. We had to change the car in the Jaffa road. We changed the car, and the van which would go to Ramallah, it arrived at Qalandiya, where there is a dead area in between Qalandiya Checkpoint and the area where the PA policemen can be with their guns. We had to create a very quick solution since the PA security men could not go next to the checkpoint with their guns. This is a very dangerous place. Thirty meters. We decided to protect the work with cameras. We invited the media, because the car had to go slow so the cameramen from different media were shooting the work coming to Ramallah or Palestine. This was the creative solution for how to protect the work.” Hourani and Salti, however, published the following account this past November in A Prior #22: “From Tel Aviv to Atarot, a private Israeli security company accompanied the van and from Qalandiya to Ramallah, Palestinian police. There was a three-kilometer section, a no-man’s land, where only civilians are allowed to passage, Israeli private security cannot tread, and neither can Palestinian national armed security. The van was unguarded by armed security, instead protection was provided by some twenty international media cameras that accompanied the van and broadcast its passage on that road live.”

Category

To be continued in No Good Time for an Exhibition: Reflections on the Picasso in Palestine Project, Part II.