“The general tenor of emotional life in Moscow, thus forming a lyrical and romantic blend, still stands opposed to the dryness of officialdom,” wrote Boris Groys in his 1979 essay “Moscow Romantic Conceptualism,” delineating the state of contemporary artistic practice in the Soviet state. In the essay, Groys discusses the work of Lev Rubinstein, Ivan Chuikow, Francisco Infante, and the artist group Collective Actions (Kollektivnye deistviya). Founded in 1976 by Andrei Monastyrski, Georgii Kizevalter, and Nikita Alekseev (later joined by Nikolai Panitkov, Igor Makarevich, Elena Elagina, Sergei Romashko, and Sabine Hänsgen), the group devised actions that took place sometimes with and sometimes without spectators, in the countryside, the city, or private apartments. Organizing conspiratorial “trips out of town,” their initial audience was asked to attend a gathering in the woods or in a field, where they might have, for example, as if by chance, come across a ringing bell under the snow. These actions were documented in photographs and short descriptive texts, among other forms; this translation into factographic elements forms another level of the work, the only one directly accessible to any audience other than those present during the initial realization.

In 2007, I had the pleasure of including a number of these photographs in an exhibition I curated entitled Romantic Conceptualism—a title that begs the question of what “conceptualism” means here, as well as what Romanticism is. That same year, Collective Actions realized a performance—again in a winter landscape outside Moscow—entitled Deutsche Romantiker (German Romantics), which amongst other elements involved period portraits of famous Romantics such as Adelbert von Chamisso, Bettina von Arnim, and Novalis affixed to trees. I couldn’t help but think of this beautiful piece as an ironic twist on my basic premise for the Romantic Conceptualism exhibition, namely that there are some interesting parallels between the German Romantics of the early nineteenth century and artists working in the realm of international conceptualism since the 1960s.

But isn’t Romanticism the antithesis of conceptualism? Yes and no; if conceptualism is understood as dialectical—as much about what it doesn’t say as what it does, as much about “pure” information as the “impure”—then there are very interesting connections.

The first methodological characteristic of conceptual art is that it radically shifts the emphasis from representation to indexicalization (in this alone it doesn’t differ fundamentally from earlier movements of modernist abstraction); rather than reproducing or illustrating the appearance of something, that “something” is evoked through a gesture, or language, or other indexical means (including, literally, signs and measures). While this may imply a devaluation of skill (in order to index, one doesn’t necessarily need to be good at drawing from life, or even at making a photograph) and originality (if there is no virtuosic skill, there will be no detectable “style” securing the distinctive authenticity of the work), these seem to be—initially, at least—side effects rather than main objectives. The main objective is rather to move away from the visual and the phenomenological (or the retinal, as Duchamp famously put it) toward the indexical, toward pointing to things in an idea-driven way (which does not preclude the use of images as long as they are in the service of this objective).

Secondly, conceptual art usually adheres to a fairly strict, reductivist ethos of economy of means (in this alone, it does not fundamentally differ from the trajectory that leads from Malevich to Minimal art). In other words, the idea is that for indexicalization to be most effective, it needs to be realized with as many elements as are necessary but as few as possible. As with an architectural model or philosophical proposition, this is at the service of either strictly securing or “closing” the meaning or, to the contrary, of allowing the work to become a kind of springboard that, like an optional (yet precise) speculation, opens up meaning—for better or worse—to the viewer’s perceptive response and intellectual continuation. A good example of the former strategy is Joseph Kosuth; a good example of the latter is Lawrence Weiner; Sol LeWitt sits somewhere in between.

The third point follows directly from the second: whether the main aim is to achieve a clarity of meaning (Kosuth), a clarity of the artwork-viewer relationship (Weiner), or a clarity of the work’s realization (LeWitt), there is a strong tendency toward dematerialization, which does not mean simply to do away with physical objecthood but to do away with the cohesiveness of the artwork in terms of where it “resides.”1 In other words, even if an object is involved—a chair, a piece of paper, a file cabinet, or whatever—or if the artist’s or anyone else’s body enacts a gesture or act that is documented—the production of physical residues—the work may still be constituted by neither a particular object nor a particular body. A relationship between things in the world is stated without necessitating a physical realization of that relationship to constitute the artwork. Rather, it may simply be constituted by the proposition of the artist (immaterial production); it may reside in the particular way something is situated or conveyed through, for example, its position in a space or publicized through press releases, invitation cards, catalogues, and so forth (distribution or circulation); it may reside in the way the viewers “fulfill” the work through their use of or response to it (“consumption” or reception); or, indeed, it may be a mixture of all three of these parameters of production, distribution, and consumption. The shorthand term for the specificities of this particular mixture is “context.” In other words, dematerialization has the potential not only to be the next logical step of reduction in formalist terms, but almost inevitably leads to questioning the way things are made, disseminated, and perceived—with obvious social and political implications.2

The three fundamental methodologies of conceptual art are intricately connected to two ideologically opposed understandings of authorship. The first is an emphatic affirmation of authorship. Freeing artistic practice from strict representation of the complex phenomenological word and the particularities of physical materiality—with the help of indexing, reducing, and dematerializing—turns the practice into a free-floating intellectual endeavor. The artist either becomes a kind of trickster who subverts the authority of the cultural tradition by suspending the parameters by which it is perpetuated (e.g., skill, composition, preciousness of the object, and so forth), or the artist becomes an intellectual master who, much like a philosopher, successively unfolds a system of analysis that enlightens us with respect to the historical obsolescence of these traditions (Kosuth).3 Either way, authorship secures the status of these endeavors as art while making them part of a consistent, or at least organized, trajectory.

The second of the two aims is precisely the opposite: to suspend authorship. By unhinging artistic practice from representation, the phenomenological, and object-based materiality simultaneously, it is freed up (at least that’s the underlying utopian idea) toward a collective process. Weiner’s “Declaration of Intent” (1969) was the model case for this. It handed the completion of the work over to the audience (or the “receiver”), namely in the way that it replaced the common imperative of performative instruction pieces (“Do this, do that …”) with the conditional form (“The piece may be fabricated …”). A conundrum remains: the one who declares the suspension of authorship paradoxically asserts his or her authorship through that very declaration; Weiner’s declaration demonstrates that the two seemingly opposing aims of securing and suspending authorship can sometimes be found in a single artist’s oeuvre, or even in a single work.

Whether trickster or master, self-aggrandizing individualist or self-effacing collectivist, all these approaches and methodologies ultimately serve the aim to enlighten, or (less dramatically) to generate thought and to inform. This may be done through straight address, or through innuendo; it may involve propositions about art or the world; it may lean toward the declarative or the performative (even though declaration, strictly speaking, is always also performative); it may employ language as its main medium, or it may not. In any case, the task is to artistically shape the process of communication (especially if no physical or visual elements are shaped) and to somehow make sure it takes place according to a plan (even if that plan involves varying levels of contingency). However, there remains the paradox of an attempt to open up the communication by closing it down, i.e. by tightly defining its parameters. Who has the authority to define these parameters, especially if we are not talking only about a single artist’s work, but about an artistic movement?

Luis Camnitzer (a German-Jewish immigrant to Uruguay who has lived in New York since the late 1960s) suggests in the context of the exhibition project Global Conceptualism (1999) the adoption of the term “conceptualism” as opposed to “Conceptual Art.” The latter is understood to be reserved for a relatively small group of artists from Europe and North America favoring a purist understanding of the practice; the former then names a varied field of activities from around the world that share a certain reductivist attitude, activities that turn art-making into a means of communication freed from representation and material presence, and not only for formalist, but crucially also for economic and social reasons of avoiding unnecessary material expenses and labor costs.4

It is this broader definition that I followed in Romantic Conceptualism. But what do I mean by Romanticism? In brief, Romanticism is not synonymous with the kitsch of love and desire (in other words, the common use of the word “romantic”), but an abbreviation for the cultural techniques of emotion, as well as for ideas of the fragmentary and the open that can be traced back to the days of early—particularly German, but also English or French—Romanticism that are, I would argue, still present and in fact prevalent today. Historically, Romanticism was—at least sometimes—an explicit, intelligent critique of the kind of thinking which supplied ideological legitimization of the logic of “material constraints” and power struggles that were an essential part of the emergence of industrialization and mass society. It also built on the conclusions that Friedrich Schiller drew from the terror regime that ruled in the immediate aftermath of the French Revolution, expressed in his very influential series of letters from 1795, On the Aesthetic Education of Man, in which he called for an aesthetic revolution premised on allowing individuals to develop their perceptive qualities—a totalization of aesthetic experience, in effect a proposal for the merging of art and life. In this sense, Romanticism is not simply an opponent of Enlightenment, but is its reflective side, an experimental and at times ironic counterpart to a systematic, rationalistic conception of reason.

Friedrich Schlegel was arguably early Romanticism’s most eminent voice. As Walter Benjamin noted in his groundbreaking study “The Concept of Criticism in German Romanticism,” Schlegel is first and foremost concerned with “reflective thinking,” which “won its special systematic importance […] by virtue of that limitless capacity by which it makes every prior reflection into the object of a subsequent reflection.”5 This expresses an important aspect of Romanticism, that it favors the fragmentary and the open over the systematic and the conclusive; it allows the mind to adjust to a contradictory reality instead of doing the opposite, namely making reality fit its own parameters. This is also why, in the words of Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy, “the fragment is the romantic genre par excellence.”6 “Each fragment,” they argue with respect to the romanticist conception of the literary text, “stands for itself and for that from which it is detached”—from the “totality of the fragment as a plurality and its completion as the incompletion of its infinity.”7 This is also at the heart of Schlegel’s idea of romantic irony, that it is the humble awareness that anything we analyze and conclude is unfinishable vis-à-vis the infinite chaos of possibilities.

What are the implications of all this for conceptual art? Sol LeWitt’s “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” (1967) includes the following: “It is the objective of the artist who is concerned with Conceptual art to make his work mentally interesting to the spectator, and therefore usually he would want it to become emotionally dry.”8 Two years later, in 1969, LeWitt published his “Sentences on Conceptual Art” in the first issue of Art-Language. In a context where Marxism, linguistics, and analytic philosophy were dominant, he turned against a purely rationalistic understanding of Conceptual art. In the first of thirty-five sentences, he proclaims: “Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists […] they leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach.”9 This is a striking parallel to what Benjamin said about the Romantics’ notion of criticism: “To be critical meant to elevate thinking so far beyond all restrictive conditions that the knowledge of truth sprang forth magically, as it were, from insight into the falsehood of these restrictions.”10 Still, in terms of LeWitt’s statement about the necessity of emotional dryness, why should a viewer not be able to find a work “mentally interesting” and be touched by it emotionally? And how should one make sure not to be touched by the mystics’ leaps to conclusions? In an attempt to distinguish the humble, anti-monumentalist stance of Conceptual art from the sublime stance of Abstract Expressionism, LeWitt threw out the baby with the bathwater, i.e. the emotional with the expressional. As I have tried to demonstrate with my exhibition Romantic Conceptualism and its catalogue, the work not only of artists such as Bas Jan Ader and Collective Actions, but also of “core members” of Conceptual art such as Robert Barry, can be understood in terms of addressing the Romanticist complex of affect and idea and of finitude and the infinite, but only as long as one acknowledges the necessity of circumventing the self-aggrandizing tendencies of the artist.11 And, in fact, early Romanticism did not necessarily promote the idea that the solitary artist-genius is the sole source of the artwork’s function and power: Friedrich Schlegel’s text “On Incomprehensibility” (1800), for example, suggests that ironic modes of writing continue to release new meanings for hundreds of years after any given author’s death.12

If we return to the work of Collective Actions, we find that the sublime does not reside in the solitary genius but in the collective, or rather in their actions. In any case, the two pieces I had the privilege to include in the exhibition were The Slogan (1977), which involved a red banner hung between trees on a hill in the countryside outside Moscow; the slogan read: “I do not complain about anything and I almost like it here, although I have never been here before and know nothing about this place” (a quote from Andrei Monastyrski’s book Nothing Happens). The other piece was Balloon (1977): pieces of calico—a type of cotton fabric—sewn together to form a balloon, which was stuffed with inflated toy balloons and a ringing electric bell; the object was then left to drift down the Klyazma river outside Moscow. The ephemeral character of these works brought artists and audience together in situations that hovered midway between imaginativeness and blankness, sincerity and irony.

What I’m trying to aim at is a question about the relationship between the “inwardness” of the artistic, poetic self and “outwardness”—an orientation to something beyond artistic communication—and the way in which that relationship is situated for a respective political paradigm in the public sphere. What kinds of encounters between people are really possible, what is the possibility of intimacy? In one way or another, I think all of the artists I will discuss pose the following question through their work: What is the possibility of intimacy between people?

But what’s the big deal with intimacy? In the age of internet dating, social networking, self-help books, reality TV shows with surveillance cameras, “I-cheated-on-my-husband” chat shows, and Paris Hilton sex tapes, the very idea of intimacy seems like a nostalgic fantasy. Intimacy is simultaneously nonexistent (in the sense of that securing actual privacy is impossible) and flooded with narcissist exaltation and public attention—intimacy turned inside-out. Feelings, affections, desires, “secrets” are on display for everyone to see. This seems to imply that during socialist times, before the advent of digital, capitalist media machineries, something like “true intimacy” existed, but I suspect the answer is not so clear-cut.

It was in 1974, when the Cold War ideological system was still securely in place, that the American sociologist Richard Sennett first published his influential book The Fall of Public Man. Remember, that was the year President Nixon was forced to resign because of the Watergate scandal, after conversations in the White House had been taped; it was also a time of economic stagnation in the USSR, when repression of anti-government activities was enacted by the KGB in order to keep Brezhnev in power.

Sennett’s position, in simplified terms, is that the delicate balance between private and public life that had been briefly maintained in Western societies during the eighteenth century, at the height of the Enlightenment, had collapsed. According to Sennett, during the Enlightenment a set of relatively strict social codes regulating distance and respect made possible truly satisfying public emotional connections, whereas the tendency in the following centuries toward a more self-indulgent, navel-gazing understanding of the individual’s psychological and emotional make-up had to be

a trap rather than a liberation. […] “Intimacy” connotes warmth, trust, and open expression of feeling. But precisely […] because so much social life which does have a meaning cannot yield these psychological rewards, the world outside, the impersonal world, seems to fail us, seems to be stale and empty. […] Western societies are moving from something like an other-directed condition to an inner-directed condition—except that in the midst of self-absorption no one can say what is inside. As a result, confusion has arisen between public and intimate life; people are working out in terms of personal feelings public matters which properly can be dealt with only through codes of impersonal meaning.13

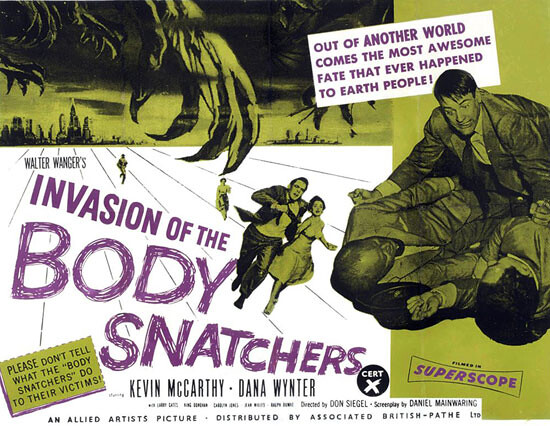

Born in 1943 in Chicago, Sennett grew up in a bohemian-proletarian, radical left milieu, and McCarthyism—the surveillance of everyday life for signs of supposed communist traitors—was a part of his experience even as a schoolboy. Showing at the cinemas were films like Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (1956), in which an alien force duplicates people and replaces them with cold, unemotional doppelgangers. This film was read allegorically either as referring to the mindless conformity of the McCarthy era or to the communist infiltration of the United States. In this sense, the McCarthyist America and Stalinist Soviet Union were indeed uncanny siblings. It is therefore not all that surprising that Sennett theorizes a complementary inversion of what he calls the “tyranny of intimacy,” the rule of narcissism and the confession of the self—namely, the “intimacy of tyranny,” the paranoid system of surveillance and denunciation that characterized both McCarthyism in the West and Stalinism in the East, though the latter was much more extreme. In the final chapter of Sennett’s book, it is Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, in her ennui, depression, and desperate desire for luxury and riches, that Sennett describes as the tragic emblem of the tyranny of intimacy, whereas the emblem of the intimacy of tyranny is “the Stalinist legend of the good little Communist who turned his parents in to the secret police.”14 Sennett’s point is that tyranny doesn’t need to take the form of brutal force; it can also work by way of seduction, which I guess is the point at which the tyranny of intimacy and the intimacy of tyranny merge. From having followed the developments in Silvio Berlusconi’s Italy over the last years, with its strange combination of voyeurism and corruption, I can say that the unity of Sennett’s phrases holds there. I’m sure there are other countries where one could identify similar phenomena.

Sennett was a student of Hannah Arendt’s, and his skepticism toward the public display of psychological matters clearly bears her influence. An insight central to all of Hannah Arendt’s philosophical work is that confession of the psychological self presents a fundamental obstacle to the political emancipation of sovereign humans in their ability to develop feelings of social interconnectedness. Hannah Arendt begins with a doubt about the reliability of the psychological self as a source of emancipation. Her deep-seated skepticism of German Romanticism—understood as a movement hailing the importance of the psychological self—is laid out already in her first major work, a biography of Rahel Varnhagen. Varnhagen was a key figure of early Romanticism, a German-Jewish writer who ran a salon in Berlin at the turn of the nineteenth century that became a meeting place for eminent figures such as the Schlegel brothers, Schelling, Schleiermacher, Alexander and Wilhelm von Humboldt, and Ludwig Tieck, to name a few. Written in Germany during the years 1929–33 and completed in exile in France in 1938, it wasn’t until 1958 that the book was published, under the title Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewess. (Writing during the growth of Fascist anti-Semitism, Arendt studies Varnhagen’s life and letters in relation to the difficult issue of Jewish assimilation.)

In short, Arendt claims that Romanticism offered Varnhagen a deceptive way out of pressures to negate her Jewish identity. Why? Because Romanticism, according to Arendt, severs reflection from fact and love from the object of love, while offering up the intimate as public in the form of indiscrete speculation and gossip. Reason and emotion become free-floating, all-pervasive fantasies—in short, Romanticism is portrayed not only as escapist, but as a seduction to Jewish self-abnegation. Although she makes a point of expressing respect for Varnhagen, Arendt almost sounds, at points, like an older sister ridiculing her younger sibling for being caught up with pubescent fantasies, or “Wunschphantasmagorien” (wishful phantasmagorias).15 One can sympathize with Arendt’s frustration with Varnhagen’s continual repudiation of her Jewish heritage, but the more important question is whether early Romanticism it is to blame. Varnhagen’s salon—and, one could say, Romanticism in its true sense—ends with Napoleon seizing Prussia. In that short interval of 1790–1806, Jewish salons like Varnhagen’s offered to the metropolitan intelligentsia a kind of utopian retreat from strict social orders and conventions. Arendt readily describes it this way, but holds this against the salons, saying they were merely “Lückenbüßer” (stopgaps) between “a perishing and a not yet stabilized form of conviviality.”16 This “stabilized” form would arrive as the Deutsche Tischgesellschaft (German Dinner Party), established in 1811 by Achim von Arnim (the husband of Bettina von Arnim, a friend of Varnhagen’s), among others. The Dinner Party banned women and Jews from membership and, in the wake of the edict of 1812 that granted basic civil rights to Jews in Prussia, was a hotbed of anti-Semitism. But does that mean that the world of the Jewish salons before the catastrophe of 1806 was merely “illusionist,” as Arendt states? To denounce early Romanticism for its role in the historical development toward a resurgence of patriotism and anti-Semitism in Prussia (as well as for Varnhagen’s increasing neglect of her Jewish heritage) seems a simple case of misdirected blame. Wasn’t Varnhagen’s salon an actual, consistent counterexample to the nationalist-chauvinist backlash of the Tischgesellschaft, not only with respect to the emancipation of Jewish intellectuals but also women intellectuals (a point that Arendt conspicuously and consistently ignores)? One can’t help but think that the Romanticism Arendt despises in her imagined Varnhagen is the Romanticism of her own time, the overblown Wagnerian sublime that became a tool of Nazism.

And this is where the notion of Romantic conceptualism comes into play: it has a kind of inbuilt anti-theatricality; it is interested in evoking the sublime but dismisses the self-indulgent puffery that accompanies its evocation. Precisely for the sake of saving the imaginative space that Romanticism opens up, Romantic conceptualists circumvent its tendencies to self-obsession, to locating essence in the artist’s soul. The idea of the open artwork demands this: if meaning is to be established through interaction with the viewer, then the artist must know humility. Maybe this is also why Romantic conceptualism sometimes comes across as the shy sibling of physical comedy. Both undermine magnitude, whether the magnitude of Wagnerian sublimity or Kantian moral superiority.

One artist who now comes to mind, especially in light of Sennett’s terms, is Jiri Kovanda. Despite Kovanda’s insistence that he’s not a political artist, I refuse to believe that it’s purely coincidental that in the mid 1970s he located his actions in Prague’s public realm. This was the period when the counter-culture that had developed in spite of the suppression of the Prague Spring movement of 1968 came under intense state repression, which triggered the human rights initiative of Charter 77, which in turn led to even harsher reactions on the part of the regime. Against this background, it is understandable that Kovanda doesn’t want his artistic project to be confused with or absorbed by protest, a confusion that would be a one-dimensional reading of both his project and of the Charter 77 movement. But that shouldn’t preclude us from reading his work in historical context. We should do so with a view to Sennett’s very fundamental sociological observations, which resonate—albeit in different registers—with conditions on both sides of the Iron Curtain. And, incidentally, the question of the connection between intimacy and control hasn’t gone away under post-socialist conditions, it has simply migrated to a substantial extent to the fields of media and commerce.

Kovanda’s aesthetic project has always been to make these two reciprocal phenomena—tyranny of intimacy, intimacy of tyranny—silently collide. Some of Kovanda’s contemporaries in Eastern Europe may have had similar aims in this respect, artists such as Karel Miler and Petr Stembera—the former in a more restrained manner closer to Kovanda’s, the latter in a more self-mutilating way, displacing the intimacy of tyranny onto his own physical body. Some Western artists did the same, including Chris Burden and Bas Jan Ader.

Kovanda negated any theatricality with clear and careful determination. His works are intimate, but reserved and discreet; they confront people’s “public” demeanor of numbed indifference, but in the most modest and unoppressive way. Moments of possible or actual sensuous intimacy between individuals are presented in a non-narrative and factual, rather than a confessional and psychological, manner. And while public apathy is suddenly punctured through a simple, tiny gesture—a gaze, raised arms, and so forth—this occurs precisely in the avoidance of spelling things out. Processes of normalization are made achingly apparent not through violent, symbolic acts, but through slight, gradual shifts. Kovanda’s humility is a means to achieving this, a way to circumvent the posture of the heroic artist that would otherwise get in the way of the work’s efficacy.

This touches directly on the question of the legitimacy of the artist. Kovanda didn’t study art in school, and it was a long time before he made a living from it. Not that he was an “outsider artist”—it was more like he snuck in, gradually, over several years. During 1977–95 he worked in the depository of the Czech National Gallery, but in the terms of his own practice, that job was something like living in the belly of the beast. In any case, his actions were not commissioned; they remained as discreet in status as in gesture.

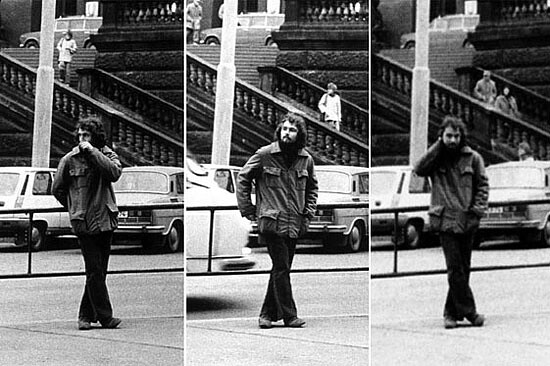

Some of the actions Kovanda executed in the open, public environment of Prague are equally ephemeral, for example Theater (November 1976), which took place at Wenceslas Square. For this piece, he followed a previously written script to the letter, in which “gestures and movements have been selected so that passers-by will not suspect that they are watching a ‘performance.’” Judging from the photos, these were predominantly gestures of being at a loss: a hand to the neck, a finger to the nose, gestures that are anything but theatrical. For Untitled (November 19, 1976), which also took place at Wenceslas Square, Kovanda interacted more actively, if still in a reticent manner, with anonymous passersby: standing with outstretched arms, forcing them to give him a wide berth.

It’s obviously no coincidence that these pieces—situated in the public realm yet resistant to revelation—take place at Prague’s Wenceslas Square, the site of many historical events from the Declaration of Independence of 1918, through student Jan Palach’s self-immolation protest against the Soviet invasion of 1968, to the demonstrations of the Velvet Revolution in 1989. But Kovanda doesn’t claim that his actions are explicit political allegories. For him, the artist is his or her own audience in the first place. But Kovanda also made works that directly involved the participation of small groups of people, which brings to mind the Collective Actions Group. One of Kovanda’s best-known pieces is an action realized on January 23, 1978, which he describes in this way: “I arranged to meet a few friends … we were standing in a small group on the square, talking … suddenly, I started running; I raced across the square and disappeared into Melantrich Street …” The photograph shows a group of seven, gathered in a circle, three of them looking at a book, while the other four are gazing after Kovanda running away from them.

Italian artist Giovanni Anselmo, usually associated with the Arte Povera movement, may seem removed from conceptualism. A large number of his pieces are emphatically concerned with materiality rather than dematerialization, with physical rather than “merely” mental or indexical tensions, with intuitive approaches to handling objects and spaces rather than pronouncedly analytical approaches—all of which are qualities that would “disqualify” you from taking the label “conceptualist.”

Yet some key works of Anselmo’s are not about the physically present, but the absent; they allude to something with a fragmentary gesture or word, rather than a physically charged object. Let’s begin with what has been described as the epiphany at the start of his artistic career. A small color photograph documents the event: the artist stands there, motionless, wearing white trousers and shoes in a steeply slanting, black lava field, while behind him are smoke and a small volcano eruption, the blue sea and the sky. The picture is accompanied by the following statement: “My shadow projected to infinity on the top of Stromboli during sunrise on 16 August 1965.” Anselmo had climbed to the top of the volcanic island that is part of the Eolic islands north of Sicily and realized that, even though the rising sunlight was hitting him at a low angle, because he was standing on a slope against the background of the sea there was no surface on which his shadow could fall.

This event marks the initiation of Anselmo into his artistic practice, the photograph and text in turn framing the moment of epiphany, which could be read to mean that neither the event nor its documentation, strictly speaking, are themselves a part of Anselmo’s oeuvre. Of course, one can see his concern with basic physical qualities and energies in this moment on top of a volcano. But there is also a counter-movement to the famous Romantic motif of Caspar David Friedrich’s solitary figure as seen from behind in nature—that figure in Anselmo’s case being the artist himself, turning towards the viewer (i.e. the viewer beholding the image), while at the same time impersonating the viewer (i.e. the viewer beholding nature). One is also tempted to point out parallels with French-German Romanticist Adelbert von Chamisso’s famous story Peter Schlemiel (1813), about the man who sold his shadow—his soul—to the devil for a sack of gold. Except that Anselmo did the opposite, suspending his shadow for the sake of a “poor” art.

Or take Anselmo’s piece Interferenza nella gravitazione universale (Effect on the gravity of the universe, 1969). The accompanying description states: “20 photos taken at intervals of twenty paces while walking towards the setting sun.” Anselmo’s set of small black-and-white photographs quite clearly set themselves apart from the kitsch residue of this Romantic trope par excellence, i.e. the tourist sunsets of countless postcards and panorama wall papers: the series of photos was taken according to a strict numerical plan (20 photos, 20 paces).

What is revealed here to be at the heart of conceptual practice, whether with Anselmo or Kovanda, is the tension associated with Friedrich Schlegel’s notion of poetry and Romantic irony:

Romantic poetry […] —more than any other form—[can] hover at midpoint between the portrayed and the portrayer, free of all real and ideal self-interest, on the wings of poetic reflection, and can raise that reflection again and again to a higher power, can multiply it in an endless succession of mirrors. […] Romantic poetry is in the arts what wit is in philosophy.17

Schlegel’s notion of Romantic poetry from 1800 resonates surprisingly with conceptual art-making of the 1960s onwards, in that both testify to a realization of a sense of disjunction between inevitably fragmentary attempts to describe the world and the infinite world itself, of a need to resolve that disjunction not by presenting an ideal of epic, synthetic unity, but by way of a scattered practice that reflects on its own character of reflection.

To give one last example from yet another political and geographical context, that of Yugoslavia in the 1960s: Tomislav Gotovac. Gotovac is an outstanding figure of experimental film, conceptualism, and performance both within and outside ex-Yugoslavia. Straight-Line (Stevens-Duke) is a 16mm film he realized in 1964: a camera is positioned in the window of a tram so that we see the long, straight tracks which run along the street in one, long static shot. We see people crossing the tracks, cars rushing by, nothing spectacular, just everyday life—but long before TV stations would adapt these kinds of mesmerizing scenes for their nighttime intermissions. In 1971, Gotovac realized Streaking, where he ran naked through the streets of Belgrade. In the following decades, he continued to make films and performances that use quotidian acts (shaving, cutting hair, begging, cleaning up) as artistic material, taking the public spaces of Titoist Yugoslavia as his conflicted stage. In more recent years, 1995–2005, Gotovac collaborated with Aelksandar Battista Ilic and Ivana Keser on the project Weekend Art: Halleluja the Hill, which, during a time of conflict in the Balkan region, took Sunday walks on the Medvenica mountain near Zagreb as performative material, documented with photographs—simultaneously fiercely ironic and touchingly idyllic.

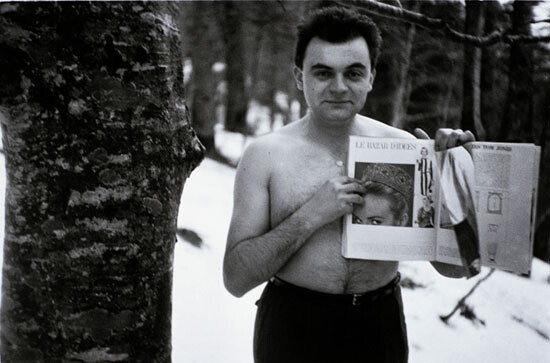

Showing Elle documents a situation the artist set up in 1962 on a winter trip to the mountain of Slijeme outside Zagreb. The six black-and-white images that comprise the series (re-issued in 2005) form a mini-film: we see the artist amidst trees, partly undressed (while he wears dark trousers), with snow in the background, leafing through a French edition of Elle magazine. He holds up an image of a woman in underwear, laughs; some images show him alone, others reveal three people, friends presumably, standing in the background. Signification slips and slides: the distance between nature and consumer society—and the distance between communism and consumer society, for that matter—is bypassed comically, as is the distance between the genders, the bodies, the artist and his audience—all of that packed into a simple, wry gesture, photographically documented.

To come to a conclusion: what seems obvious here is that in many of the works I have discussed, “the public” is tested as a terrain for intimacy, precisely because intimacy is no longer protected by a strict sense of “the private.” What these artists might have in common is that they test the limits of intimacy by communicating those limits, not in confession but through acts of deviance that say: yes, I have feelings, but what precisely they are I will not reveal. I take part in the game of self-exposure, but in that very act I manifest my insistence on an autonomous sphere of thought. What remains is the gesture, the act, the communication, but not the confession of the artistic soul.

The crucial difference between dematerializing the art object—famously suggested by Lucy R. Lippard and John Chandler in their article “The Dematerialization of Art,” first published in Art International 12:2 (February 1968): 31–36—and working without material basis in the first place, i.e., dealing with ideas, has already been pointed out by Terry Atkinson of Art & Language in his response “Concerning the Article ‘The Dematerialization of Art.’” See Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 1999), 46–58.

See Luis Camnitzer’s critique of a formalist understanding of dematerialization, Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2007), 29.

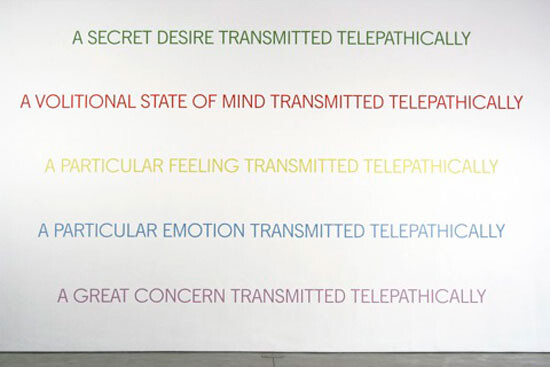

Think, for example, of Robert Barry’s Telephatic Piece (1969), his contribution to a group exhibition in Canada that consisted of a written statement that he would telepathically transmit, as it was not “applicable to language or image.”

Luis Camnitzer, op. cit., 22–24.

Walter Benjamin, “The Concept of Criticism in German Romanticism,” in Selected Writings, Volume 1: 1913–1926, ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996), 123.

Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy, The Literary Absolute: The Theory of Literature in German Romanticism (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1988), 40.

Ibid., 44.

Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” Artforum 5:10 (Summer 1967): 79–84. Also see Alberro, op. cit., 12.

Sol Lewitt, “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” Art-Language 1:1 (May 1969): 11–13; reprinted in Conception: Conceptual Documents 1968–1972, ed. Catherine Moseley (Norwich, UK: Norwich Gallery, 2001), 82.

Walter Benjamin, op. cit., 142.

Romantischer Konzeptualismus / Romantic Conceptualism, ed. Ellen Seifermann and Jörg Heiser (Nürnberg: Kunsthalle Nürnberg and BAWAG foundation Vienna, Kerber Verlag, 2007).

Friedrich Schlegel, “On Incomprehensibility,” in Classic and Romantic German Aesthetics, ed. J. M. Bernstein (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2003): 297-307.

Richard Sennett, The Fall of Public Man (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 1977), 5.

Ibid., 337.

Hannah Arendt, Rahel Varnhagen: Lebensgeschichte einer deutschen Jüdin aus der Romantik (München: Piper, 2008), 65 (my translation).

Ibid., 71 (my translation).

Friedrich Schlegel, “Athenaeum Fragments, no. 116,” in Friedrich Schlegel: Philosophical Fragments, trans. Peter Firchow (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1991): 31–32.