I do not complain about anything and everything pleases me despite the fact that I have never been here before and know nothing about these parts.

—Collective Actions slogan, January 26, 1977, Leningradskaia railroad, Frinsaovka station1

In 2005–6, I experienced a coup de foudre—a lightning blast of admiration—when I discovered Collective Actions and their performances in the snow. Later I attended Boris Groys’s talk at his Total Enlightenment exhibition in Frankfurt (2008) where he described the physical experience of travelling to snow fields, participating in mysterious actions, the return, and the months-long discussions and documentation that constituted other dimensions of the project. Much of this documentation was displayed in the Russian Pavilion this summer at the Venice Biennale, curated together with the doyen of the group, Andrei Monastyrsky.2

Groys baptized “Moscow Romantic Conceptualism” in the review A-YA in 1979, later excising (exorcising?) the word “Romantic,” a move that specifically intrigues me. During our Courtauld Institute collaboration last spring, I was introduced to Jorg Heiser’s Romantic Conceptualism exhibition from 2007, which explored the revitalization and dérive of “original” conceptual art.3 Its title preceded our new terminology—Expanded Conceptualism—for the Tate Modern conference of March 2011.4 Groys’s The Total Art of Stalinism (1988; English 1992) marked a “turn” at the moment of perestroika; it broke down the Manichaeism of Cold War stereotypes (Malevich good, socialist realism bad) from which current revisions of the twentieth-century canon proceed. What I wish to interrogate here is both the presentation of Moscow Conceptualism as entirely exceptional and the “suspension of disbelief” (the term coined by Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge) that its chroniclers require of a Western audience, as they insist upon an autochthonic movement, born in snow.

Analysis of the movement by non-participants tends to follow the materialist, formalist pragmatism of secular American art history and American conceptual art (bearing in mind its absorption of French phenomenology and “theory” during the 1960s and 1970s).5 The philosophical, mystical background implicit in the Russian mind-set is hardly explained; it remains the “untransmissible secret.” In fact, to read A-YA is to become aware of the insistence on eschatology in Russian art that goes beyond all irony, all quotation—and a quality of writing, half hidden in translation, which has an ineffable strangeness. Like looking into snow, one is aware of both crystalline transparency and deep opacities that indicate “other” intellectual, philosophical, and spiritual dimensions. One perceives but can only partially decipher. What, of the essence of things, is lost in translation? And what is lost through time? Today’s critics and curators of the “new” Russia are also—if not equally—estranged from a lost world of meaning. I quote from Groys’s article, published with his photograph (a provocatively dangerous action) as the first article in A-YA 1:

In England and America, where conceptual art originated, transparency meant the explicitness of a scientific experiment clearly exposing the limits and the unique character of our cognitive faculties. In Russia, however, it is impossible to paint a decent abstract picture without reference to the Holy Light. The unity of collective spirit is still so very much alive in our country that mystical experience here appears quite as comprehensible and lucid as does scientific experience … Unless it culminates in a mystical experience, creative activity seems to be of inferior worth.6

A-YA (1970–86), the last great twentieth-century art periodical, was trilingual, produced near Paris and distributed in expatriate communities. It reported on events past and present in the USSR, and on expatriate activities from Jersey City to Tel Aviv, at the moment of maximum Jewish emigration from the USSR.7 These facts alone should alert us to the special nature of the images we now love to see in Frankfurt, London, Venice, or New York. Does A-YA’s openness, its connections, explain why it has been “disappeared” from contemporary retrospectives? Today we enjoy not only Moscow Conceptualism delayed, but a “delay in snow,” an operation that constantly brings us back to Collective Actions and their magical, originary moment of vastness, isolation, revelation, and political impudence. Purity and danger—an irresistible combination.

My title, “Moscow Romantic Exceptionalism,” uses the model of France as a “cultural exception”: the well-known exception culturelle française.8 The Marshall Plan for the reconstruction of postwar Europe involved promoting American culture as well as economic deals. The French increasingly called upon their self-appointed status as a “cultural exception” to justify special subsidies, particularly for the French film industry menaced by Hollywood. The “wine versus Coca-Cola” wars were not just about difference but also a fear of cultural “contamination.” I wish to put vodka into the equation: the burning liquid assessed via its purity and transparency, the drink for the snow that banishes cold and pain. Why is Moscow Conceptualism ring-fenced with an “exceptional” status? What is the fear of contamination, when it embraced various practices aligned with those in Europe, Eastern Europe, and America? The “delay in snow” requires a suspension of disbelief to maintain our faith in its miraculous genesis and now decades-long resurrections.

Interviews, investigation, and comparisons could perhaps one day build up a body of knowledge equivalent to that surrounding the birth of cubism in Montmartre or of conceptual works and performances in New York. Western art magazines were accessible in Moscow; we are aware of the transmission of images and ideas, of the importance of conversation and, beyond imitation or appropriation, more complex models such as the Situationists’s dérive or Harold Bloom’s idea of creative “misprision.”9 At the risk of banality, then, I wish to make some comparisons.

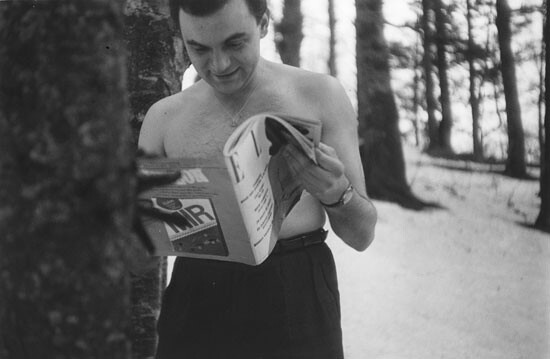

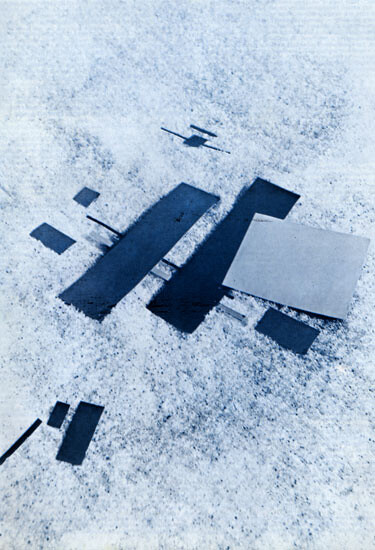

Performances in the snow: Tomislav Gotovac’s Showing Elle, made apparently as early as 1964, took place in the mountain woods of Slijeme, near Zagreb, in the presence of a group of friends and a skilled photographer. Stripped to the waist, Gotovac posed reading Elle magazine from France.10 In 1969, Robert Morris walked, mirror in hands, through a snowy landscape in America to make Mirror, a 16 mm black and white film. Lucio Fanti’s Poetry Readers in the Snow (1975) is a fantastic projection in oil paint, created in France with no knowledge of Moscow Conceptualism—a coincidence indeed, yet a satire, informed by Althusser, on the loss of the Soviet project, based on the artist’s contemporary perceptions and past memories of the USSR.11 Surely, one could argue, Robert Smithson’s Yucatan Mirror Displacements (1969) suggested Francisco Infante’s mirrors placed in landscapes of 1976 (reproduced in A-YA 1 in 1979)?12 (Now reproduced in color on Infante’s website, these works name his wife, Nonna Gorunova, as collaborator, a significant gesture. Conceptual artist-wives in East and West have only recently received attention). A-YA 3 (1981) also reproduces Infante’s breathtaking Malevich experiments.13 The elements of fun, playfulness, even banalization—bringing Malevich down from his cosmos to a series of flat colored shapes on the snow—was surely more evident at the time they were made. With Mirror Piece in Snow (1977) Infante finally joins Robert Morris.

The “exceptional” nature of every piece of art relates to its production at a certain moment: the conjunction of synchronic and diachronic axes, the intersection of time and space. Despite the different experiences or mind-sets at stake, parallel phenomena—at the level of grand narratives—do not exist: take the atom bomb or the space race, the driving economic imperatives of the Cold War. Espionage, expertise, and intellectual as well as economic investments prevailed: “delay” was not an option. “Art in a society without a market” may indeed involve stories from the USSR that are more fascinating than the well-known trajectories of Smithson and Morris, such as how Infante, working for trade fare installations, stole mirror foil, or how he procured West German cameras. These “small stories” relate to the artist as individual and a specific oeuvre; but as for parallel phenomena, certain conclusions are obvious. On ne né pas conceptuel, on le devient—one is not born but becomes conceptual—to paraphrase Simone de Beauvoir.

“Delay” was by no means a purely Soviet problem. Take the 1970s conjunction between conceptual art and the hyperrealist movement in painting. If we date Anglo-American conceptualism to the mid-1960s, its official arrival at the Paris Biennale was in 1971—simultaneously with American hyperrealism. The conjunction “conceptualism-hyperrealism” was repeated again at the Kassel Documenta of 1972. (The October group’s anthology, Art Since 1900, names this moment the “triumph of conceptual art in Europe,” obliterating hyperrealism as a movement altogether.) An influential show that put together conceptual and hyperrealist art in Aachen and Paris in 1974 coined the phrase “hyperrealized conceptualism.”14 The paintings of Boulatov and Kabakov must be seen in this context.

In Western Europe, the postwar realisms extended from Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon to the “existentialist” Bernard Buffet, or to the socialist realists André Fougeron and Renato Guttuso. This was followed in the mid-1960s by a politically aggressive riposte to American Pop artists such as Rosenquist, combined with images corresponding to New Wave film. Using images projected with slides or an epidiascope, these “Narrative Figuration” movements answered hyperrealism, perceived as American triumphalism. Communist, neo-Marxist, and Maoist artists from Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Britain, and America celebrated Lenin’s centenary in 1970 in the huge German touring show Kunst und Politik. Lucio Fanti, who exhibited here, was already perplexing the French and Italian communist apparatchiks with his own critical pieces when the world outside the USSR was rocked in 1974–5 by the publication of Solzhenitzyn’s Gulag Archipelago.

Fanti turned to metaphors of snow and fog at a particularly intense time of doubt and disarray: see The Fog of Ideology (1974) or Poet in the Fog (Mayakovsky) (1975). Brezhnev’s period of “stagnation” marked a kind of freedom in stasis—what Groys called at the Moscow conference a “happy period”—conveyed so well by the frozen motion of Boulatov’s figures. Fanti’s motifs of Soviet monuments may be compared with Boulatov’s Natasha (1978–9), where his wife, wearing orange in the snow, projects vibrantly towards the viewer—a Soviet statue in the background. In each case—seen from inside or outside the USSR—past ideology frozen in sculpture becomes increasingly obscured. By 1977, the exhibition New Soviet Art at the so-called Biennale of Dissent in Venice showed work from the USSR from the 1950s to the present; Eric Boulatov’s Horizon was the star. Every single work had been illegally exported over the previous few years; collectors were based in Prague, Paris, New York, and cities in Germany and Italy. Igor Golomstock, the curator Alexander Glezer, the sculptor Ernst Neizvestny, and artists Alexander Melamid and Lev Nussberg (all recently emigrated) spoke at the related conference, belying the myth that no Soviet artists were present.15 This large international meeting was five years before the poet Vsevolod Nekrassov’s talk “Photorealism in Eric Boulatov’s Painting” at the Photography and Painting conference in Moscow of 1982.16 Yet never once have I encountered any contextualizing work about Boulatov, nor a serious description of his shift from work produced for the Surikov Institute in Moscow (1952-8) to his achieving of photographic effects similar to his European contemporaries. (Boulatov claims that his microscopic stippling in crayon or paint does not use projection.)

Let us now turn to the question of Ilya Kabakov:

I wrote notes on: the direct correlation of the height of a culture to the quantity of its garbage

The recycling of trash as raw material for paper, glass, and rag rugs

The laws concerning recycling

The increase of value of trash as it ages

The legal status of flotsam and jetsam

Social garbage, and expulsion from society

Trash as a breeding place for microbes, but also on microbes as representatives of trash and transformers of cellulose into sugars, a hypothetical future study of the archeology of our epoch. I found shards of glass to be full of excitement, rusty knobs to be full of recollections, dead flies could break my heart.17

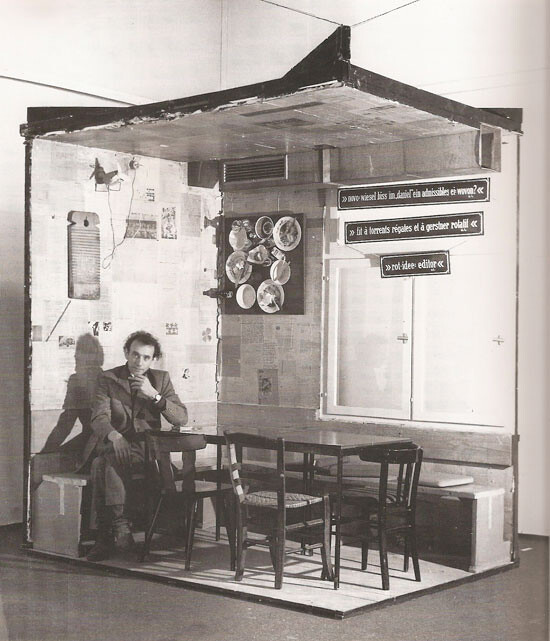

Flies—as one knows in Moscow—could break Kabakov’s heart: from Queen Fly (1965) to his Life of Flies series of 1992. But the quotation above is not Kabakov expatiating on Soviet garbage. It is the Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri in 1971, somewhere in the countryside near Berne. Just to explore a “world before Kabakov”: A Corner of the Spoerri Restaurant (1968) makes—probably for the first time—the joke of the whole room (or whole world) as “ready-made,” offering the idea of an avant-garde work that is entirely kitsch. We see kitchen stuff, intimacy, the suggestion of conversations—though not in the Soviet communal apartment. Spoerri’s vertical wall installation of 1961 displayed the kitchen pots and pans and even the art of his friends, all imbued with the post-Kurt Schwitters, post-Robert Rauschenberg, post-Second World War “poor” junk aesthetic of the times, where “everyday life”—far more than Marcel Duchamp—was the watchword. (Moscow Conceptualism lacks the Duchamp fixation of its English and American counterparts, despite the mention in A-YA 2 of “Duchamp’s ‘ready-mades,’ which are so well-loved in Russia.”18) Spoerri was affiliated with critic Pierre Restany’s Nouveau Réalisme movement. A photograph of Spoerri’s Table de Ben (1961) shows Fluxus-connected performance artist Ben in Nice, Nouveau Réalisme’s southern outpost, standing outdoors beside a Spoerri composition attached to wire netting: a moveable feast.

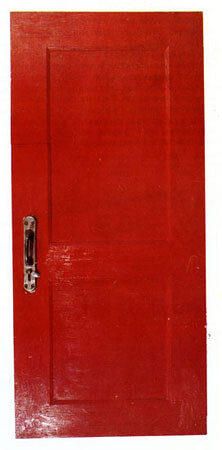

Art magazines were also moveable feasts. The curator Andrei Erofeev, who saved so much of the Soviet conceptual art heritage now in the Tretiakov Gallery, points to the probable influence of Robert Rauschenberg on Mikhail Roginsky, whose Red Door (1965) is an aspirational “ready-made” (though not an actual door), preceding the Sovietized, “expanded” Nouveau Réalisme of Kabakov. He corroborates the evident impact of Nouveau Réalisme on BorisTuretsky’s assemblage Junk (1974), also in its collections. The visual ideas probably arrived through magazines, he says, like bottles retrieved from the waves.19 What is the epistemological difference between these Soviet works and a European contemporary? In A-YA 3 (1981) we discover that Roginsky, who lived in Paris from 1978, read Andrei Platonov and was struck by the writer’s alienation from what surrounded him, by his idealism, his existence in an abstract world, his sadness. It seemed that the whole point of life, Roginsky concluded, was to sacrifice and to serve. After walls, doors, and floors, Roginsky started painting cans of food: what he saw as “ugly” contemporary objects.20 Ilya Kabakov’s floor installation on newspaper, Wooden Chest and Objects (1981), also in the Tretiakov, is contemporary with Roginsky’s reflections; it includes tins with labels, immediately inviting connections with the tins of artist and poet Dmitri Prigov.

Prigov is, of course, a multifaceted figure whose work from this period shifts between two worlds: visual art and concrete poetry.21 (Of course Kabakov’s own work contains sound-pieces integral to his installations). Just as Clement Greenberg combined the abstract practices of the American Jackson Pollock and the Russian émigré Mark Rothko, the Judaic minimalism of Barnett Newman and the post-European figurative heritage of Willem de Kooning—all under the label “Abstract Expressionism”—so “Moscow Conceptualism” (even Groys’s improbable new term “Communist Conceptualist Art”) can combine hyperrealist painting, junk installations, concrete poetry, performance, and documentation: all part of the strategic operation.22 Vsevolod Nekrassov, friend of Boulatov, first encountered Western concrete poetry in 1964 via an article in the Soviet journal Inostrannaia Literatura (Foreign Literature) that featured Eugen Gomringer’s poem “Silencio” (1954).23 Prigov’s genius was to pervert Soviet slogans in his blocks of text (just like the Collective Actions’s banners in the snow): “We are grown by the Party [Stalin erased] for the joy of the people.”24 Again we encounter both lateness and transformation.

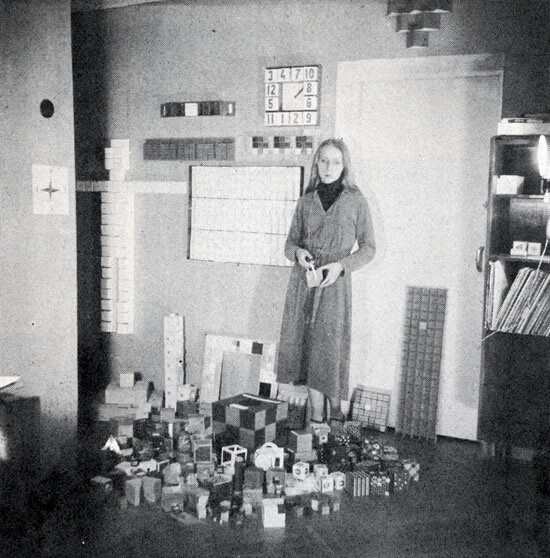

The concrete poetry world was international; it must now be stretched in time as well as space, from Carl André’s Map of Poetry, Sculpture, Words (1966) to the “land performance” poem Imagination Zone by Jaroslaw Koslowski,which recommended placing signboards everywhere (“in institutions, offices, railway station buildings, streets, squares, riverside, lakeside, sea, land, sky, etc. … for mass production and universal distribution”).25 In contrast, Eugeniusz Smolinksi’s Biography photopiece of 1974 (with shovel) shows inspiration on the move: from concrete poetry to an overt (ironic?) imitation of Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965). Such was the international context when Rimma Gerlovina’s conceptual books and three-dimensional pieces were conceived in the early 1970s in Moscow. Her “combinational play-poem” Paradise, Purgatory, Hell Game (1978), reproduced in A-YA 1, is another classic Tretiakov piece.26 How poignant to see her image, that of a brilliant Slavic language expert and philologist, in her Moscow studio prior to emigration. A-YA 4 (1982) reported on the Russian Samizdat Art exhibition in New York, designed and curated by Rimma with her husband Valery Gerlovin.27 In Ronald Reagan’s America, which was celebrating with the art of Julian Schnabel and Keith Haring, this art went down like a lead balloon.

Another coincidence belies the idea of the “exceptional” nature of the Moscow Conceptualism’s preoccupations: the apparently antithetical conjunction between Malevich and Stalin. The third issue of Paris’s new review Art Press in December 1977 (a magazine initiated with articles on Kosuth) sported a cover titled Stalinisme toujours vivant (“Stalinism still alive”). This referred not just to Soviet but to French Stalinism. Contrast this with a whole section on Malevich and suprematism in the issue, including a timeline and bibliography covering the explosion of Malevich scholarship from 1970-77. The first issue of A-YA in late 1979 coincided with the Paris-Moscow exhibition at the new Centre Pompidou in Paris and a Russian dissident political protest that included a fake Malevich coffin brought into the museum. The reciprocal show, Moscow-Paris, was held June–October 1981 at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. (Its supremely important role—including its rich catalogue—in the drive towards perestroika has been underestimated.) A-YA 3 (1981), with its article on “The Malevich Complex” and its photographs of Malevich’s funeral, continued to focus, antithetically, on socialist realism.28 In A-YA 5 (1983) Andrei Siniavsky’s article “Meeting in Naples” recalls his dismay at seeing Stalinism alive and well in Italy in 1976; having denounced socialist realism in the West in 1959 at his peril, he sees posters declaring “Long live Stalin and the dictatorship of the proletariat!”29 This constant conjunction—Malevich/Stalin—subtends the essential premise of Groys’s Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin, in which Stalin the demiurge fulfills the constructivist project to recreate the world as a total work of art.

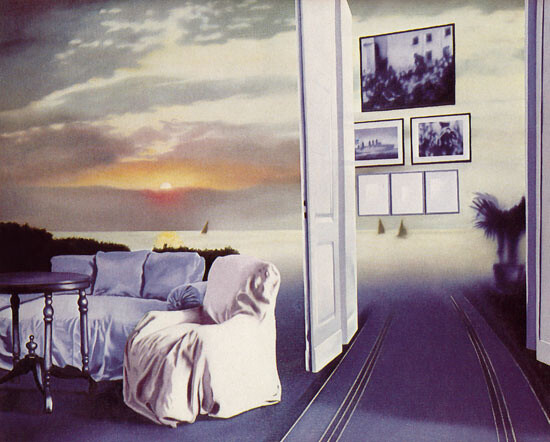

In the West—and after the euphoric Lenin exhibitions and celebrations of 1970, including in Paris’s Grand Palais, where Isaac Brodksy’s Lenin at Smolny (1935) was shown—the enthusiastic intellectuals of the still Stalinist, Moscow-controlled communist parties were full of embarrassment, guilt, and conflict when Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago was published. The political, cultural, and affective power of Western Stalinism (particularly in France and Italy, completely reconstructed after World War II with American money) counteracts the Soviet and Russian conviction that Stalinism and post-Stalinism were specifically national problems. This was not the case. Hence Fanti’s Lenin’s Armchair in Smolny, 1917 (1975) (after Brodsky), expressing the loss of Father, of patriarch, of the communist “family,” may be seen as a work of “Parisian Romantic conceptualism.”

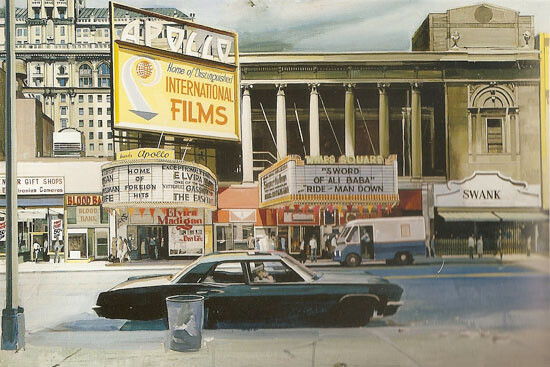

The Western Romantic Conceptualists (European narrative painters of the 1970s) detested hardcore American hyperrealism, such as Richard Estes’s Apollo (1968), however critical its intention. Referring to the American manned lunar space flight, Apollo celebrates the commodities that the USSR lacked and the vulgarity of the Coca-Cola culture that the French despised. Both France and the Soviet Union were constantly conscious of their “exceptionality,” predicated upon their own economic inadequacy. Yet dialogue with the enemy was always a dialogue of desire, and softer-focused, more innocent American work such as David Kessler’s Jim, Weyman, Peter, End of Roll Vacation Slide (1976-77) has great parallels with a soft-focus photo-based realism that moves, within a generation, to paintings such as Semyon Faibsovich’s Tchernychevsky Street (1991) or the photographs of Boris Mikhailov. Even in the A-YA period, however, an alternative “Sharp Focus Realism” based on American-inspired commercial advertising and Technicolor film was used by Ilya Kabakov in juxtaposition with his pure text pieces: see Deluxe Room.30

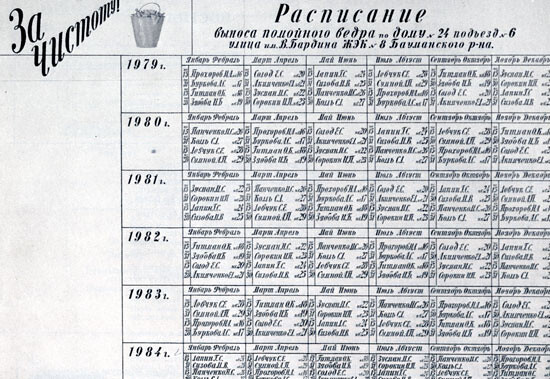

Kabakov’s texts and text-pieces—both pieces of everyday life and parodies of Soviet bureaucracy—anticipate Groys’s claim in the Communist Postscript about the linguistification of society.31 “The Communist Revolution is the transcription of society from the medium of money into the medium of language—a linguistic turn at the level of social practice.” He goes far beyond Benjamin Buchloh’s famous thesis about conceptual art’s mirroring of the “aesthetics of administration”:

In Soviet communism, every commodity became an ideologically relevant statement, just as in capitalism every statement becomes a commodity. One could eat communistically, house and dress oneself communistically—or likewise non-communistically, or even anti-communistically. This meant that in the Soviet Union it was in theory just as possible to protest against the shoes or eggs or sausage then available in the stores as it was to protest against the official doctrines of historical materialism. They could be criticized in the same terms because these doctrines had the same original source as the shoes, eggs, and sausage—namely the relevant decisions of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU.32

Just as God was once thanked for bread and wine—or for the stripes on the melon skin— the system is perceived to have produced the egg. Komar and Melamid’s Eat Art performance with Pravda-burgers (1977) is a carnivalesque confirmation of Groys’s claim.

When artists emigrated (mostly with the Jewish exodus that peaked in 1979 before the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan) their reception in the West was not what they had expected. Moscow Conceptualism’s romantic, philosophical, and eschatological dimensions were lost in translation. It fell flat—too late. Most artists (Komar and Melamid seem the exceptions) were disliked by White Russians, disliked by the Western Right since they represented the Left, and disliked by the Western Communist/Marxist Left (and its art aficionados) for their anti-communism. “I came uncertain and afraid, full of clever hopes,” said the poet Gerlovina; she faced tough times. In fact, Groys has claimed Stalin was the only internationally recognizable emblem of the USSR on par with Warhol’s Maos and Marilyns; hence his reappearance in post-emigration works such as Leonid Sokhov’s Stalin and Marilyn (1992). Groys also spoke of the Soviet male’s Oedipal dilemma—how to be as great as Stalin—and the masochistic admission of defeat it entailed. Surely Groys’s Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin (1988) partakes of the same logic as Komar and Melamid’s Stalin and the Muses (1982)? Published in A-YA 5 (1983), this was used as the cover for The Total Art of Stalinism in 1992. Critical and retrospective, The Total Art of Stalinism also relates to the German Historikerstreit—a debate about the Right and the evolution of totalitarianism—most notablyto Carl Schmitt’s ideas of Political Romanticism and Political Theology. 33 Groys’s interrogation of the Stalin era is thus informed by concepts that go beyond the comparison of totalitarianisms made in Igor Golomstock’s Totalitarian Art (1990).

Yet even after the inevitable Cold War defeat and perestroika, after emigrations and the dissolution of the A-YA nexus, the USSR kept up its panoply of power, masculinity, and cruelty. With an image of the staging of the twenty-fifth congress of the CPSU in 1986, I wish to argue finally that the loss of the Soviet Union is not only that of an empire of the Word, as Groys claims. It is also the loss of a visual empire of Light, from the black and white checkerboard and rays around Lenin, dominating his congressmen, to the light of Boulatov’s paintings, which, overlaid with slogans, switch incessantly—across a period of thirty years—among Soviet landscapes, cloudscapes, and the black and white of Malevich (see That Is What it Is [2001]). Moscow Conceptualism and its progeny suffer from repetition compulsion, from Komar and Melamid’s Work with Malevich (1990–91) to Blue Noses’s ever underdead Lenin or Blue Soup’s Way Out (2005) with its eerie animation of Brodsky’s Lenin, where only the empty chair remains.34

The light and colors in the cracked, dirty Soviet corridors or dark-brown, wire-filled basement staircases where these works of art are displayed signify the Soviet Union as total installation that is so rapidly disappearing. This installation—this Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin—is more precious, in our knowledge of its immanent disappearance, than the new art itself. Here is the “Holy Light,” symbol of the “unity of collective spirit,” the “mystical experience” of Groys’s originary statement. Light is present today in his metaphors when he talks of “the effulgence of evidence radiated by Hegel’s paradoxical discourse,” or of communism itself as “a flame that had been ignited and kindled by logical paradox”—the light-filled paradox that is the very premise and methodology of The Communist Postscript.35

Dmitri Olchanski recently predicted the disappearance of Russia as we know it within the next ten to twenty years.36 Contemporary artists such as Olga Chernycheva, with her photographs of rusty garden allotments and sad Soviet faces, are the lyric poets of this disappearance, as are several Western artists and photographers.37 With this disappearance, only “last survivors” will remain—those who partook of the Soviet mind-set—as opposed to those who, locally or globally, constitute the living postscript to Soviet communism.

I would like to conclude by looking to Diagonal (1978), a paradigmatic Moscow Conceptualist painting by Oleg Vassiliev published in A-YA 2 (1980).Arms outstretched, a figure zooms towards us through a snow-covered forest (itself the white paint of a Malevich)—or rather zooms backwards like Benjamin’s Angel of History. In the society of no market where man owned nothing, he de facto owned everything. Vassiliev’s post-constructivist interrogation of a post-perspectival space going back into the natural world corroborates this society of Light as well as the Word.38

Groys’s writing functions as a philosophical sieve, separating the grain from the chaff and then distilling the grain, like a vodka maker, into a burning transparency. The A-YA papers in the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers tell us not only about the danger of smuggling texts and the labor of critical and art historical writing, photography, and translation. They also reveal bickerings, jealousies, protectionism—even anti-Semitic antagonisms and strategies of denunciation. The literary issue, A-YA Literaturniy 1 (1985), sketches the tragic background of a poet such as Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov, who spent decades of his life in labor camps, from 1929-1953.39 In Venice this summer Andrei Monastyrsky interrupted the snow-clad idyll of Moscow Conceptualism and the cold light of its archives with a dialectical proposition: a stark evocation of the gulag.

Coleridge declared that the “willing suspension of disbelief … constitutes poetic faith.”40 My poetic faith in Moscow Conceptualism as an exceptional, discrete phenomenon is rocked by the evidence; I disbelieve in the presentation of its archive as the material evidence of a society of the Word alone. I am aware that, as Erofeev says, isolationism is a Soviet symptom but aware too that the cloud of my unknowing also covers like snow.

This Collective Action is reproduced in color on the front of A-YA 4 (1982). It reappears as the cover of Groys’s Total Enlightenment: Conceptual Art in Moscow, 1960–1990 (Frankfurt: Schirn Kunsthalle, 2008) and was the transposed leitmotif of the Russian Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 2011.

I also saw Parallel Play: Moscow Conceptualism, 1970–1990 (Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, 2009) and subsequently Field of Action: The Moscow Conceptual School in Context (Calvert 22, London, 2011), a special adaptation of an exhibition originally held at the Ekaterina Cultural Foundation (Moscow, 2010). Today we are also informed by Groys’s new anthology of Moscow Conceptualism texts, History Becomes Form, as well as Matthew Jesse Jackson’s The Experimental Group and the Ekaterina Foundation’s exhibition catalogue Field of Action: The Moscow Conceptual School in Context, all published in 2010. Evidently all art shown, all texts read, exist in the now; interpretations and rereadings hold contemporary truths.

Our Andrew W. Mellon Foundation-sponsored MA course (Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London) was called “Global Conceptualism: The Last Avant-Garde or a New Beginning?”

Romantic Conceptualism, Kunsthalle Nürnberg, BAWAG Foundation, Vienna, 2007; Expanded Conceptualism, Courtauld Institute of Art with Tate Modern, London, March 18–19, 2011. See →.

See the conference French Theory: Réception dans les arts visuels aux Etats-Unis entre 1965 et 1995 (Wiels Contemporary Art Center, Brussels, May 11–14, 2011).

Boris Groys, “Moscow Romantic Conceptualism,” A-YA 1 (1979): 4.

A-YA is the subject of both an MA thesis and current PhD research by Elizaveta Butakhova at the Courtauld.

See Serge Regourd, L’exception culturelle (Paris: Puf, 2004).

See Bloom, “Clinamen or Poetic Misprision,” The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 19–45.

The piece was shown in Heiser’s Romantic Conceptualism (2007) and Gender Check (Vienna and Warsaw, 2009–10).

See Sarah Wilson, “Althusser, Fanti: The USSR as Phantom,” The Visual World of French Theory: Figurations (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 97–122.

“Francisco Infante,” A-YA 1 (1979): 38–41. (This issue also includes Kazimir Malevich, “Concerning the Subjective and the Objective in Art and Generally,” trans. T. and A. Schmidt, 42–43.) Compare Robert Smithson, “Incidents of Mirror-Travel in the Yucatan,” Artforum (September 1969): 28–33. Infante is open about his reading in Moscow’s Foreign Language Library.

“Francisco Infante,” A-YA 3 (1981): 38–40. (Also included in this issue was Igor Golomstock, “The Malevich Complex,” trans. Robert Chandler, 41–44; and K. Malevich, “To the Innovators of the Whole World,” trans. Jamey Gambrell, 45–49, which includes photographs of Malevich’s funeral.)

Wolfgang Becker, “Le conceptualisme hyperréalisé,” Art conceptuel et hyperréaliste: Collection Ludwig–Neue Galerie, Aix-la-Chapelle (Paris: Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, 1974).

For all manifestations and photographs of ex-Soviet participants in many sections see “Il dissenso culturale,” La biennale: eventi del 1976–77 (Venice: 1979), 528ff, photos 826–864.

See Vsevolod Nekrassov’s “Le photoréalisme dans la peinture d’Erik Boulatov,” given at the conference Photography and Painting (Moscow, 1982) and published in Boulatov (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1988), 23. See also Boulatov’s portrait of Nekrassov, 1981–5, (p. 55) based on a photo reproduced in the literary issue of A-YA (1985).

Daniel Spoerri, Postface to Krims-Krams-Magic (Hamburg: Merlin, 1971). My translation from the French is from Daniel Spoerri (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1990), 88.

V. Patsyokoc, “Project, Myth, Concept,” trans. Jamey Gambrell, A-YA 2 (1980): 3.

Confirmed in conversation with the author, October 21, 2011. See Andrei Erofeev and Jean-Hubert Martin, eds., Nonkonformisten Russland, 1957–1995, Sammlung des Staatlichen Zarizin-Museums Moskau. (The corresponding exhibition was shown in the Documentahalle Kassel &leftbracket1995&rightbracket and at Moscow’s Manege).

Interview with Mikhail Roginsky, A-YA 3 (1981): 22.

See Stephen Bann, Concrete Poetry: An International Anthology (London: London Magazine Editions, 1967). See also Elizaveta Butakhova, “Dmitri Alexandrovitch Prigov as Concrete Poet: Sculpting in Ink, Writing in Blood,” Dmitri Prigov (Zurich: Barbican Art Gallery, 2011), 273–279 (especially note 6).

Boris Groys, “Communist Conceptual Art,” Total Enlightenment, 28–34. (“Moscow Romantic Conceptualism” from A-YA 1[1979] appears unreferenced, 316–22.)

See “Vsevolod Nekrassov,” A-YA Literary Issue 1 (1985): 36–47.

“Dimitry Prigov,” A-YA 1 (1979): 52. Also in A-YA Literary Issue 1, 84–99.

See Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, “Early Visual and Polyphonic Poetry” →.

See Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, “Early Visual and Polyphonic Poetry” →.

For reception, see Nadim Samman, “Between the Gulag and the Guggenheim: (Post-) Soviet Artists and New York in the 1980s and 1990s” (PhD thesis, Universtiy of London, 2011), Chapter 2.

See note 11 and Mikhail Aksyonov Meerson, “The Art of Socialist Realism,” trans. Catherine A. Fitzpatrick, A-YA 3 (1981): 58–59. This was preceded by Komar and Melamid, “The Role of the War Ministry in Soviet Art,” trans. Jamey Gambrell, A-YA 2 (1980): 50–53; and followed by C. Core, “Jubilee Reflections on the Academy of Arts,” trans. K. G. Hammond, A-YA 7 (1985): 52–58.

A-YA 5 (1983): 54. The poster reads “Viva Stalin, 5-3-53–5-3-76, Viva la dittatura del proletario! (See Yves Benot, L’Autre Italie (1968–1976): Problèmes de la dictature du prolétariat [Paris: Maspero, 1977]).

Deluxe Room (1981) opposite the text piece “Taking Out the Garbage Pail” (1980) in A-YA 6 (1984): 28–29. (See also Sharp-Focus Realism, Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, 1972).

Kabakov’s piece on the self-reflexive “TEXT” (in the context of his knowledge of Duchamp and Pop Art in “Semidesiatie gody,” undated manuscript) is discussed in Groys, The Total Art of Stalisnism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 86–7.

Groys, The Communist Postscript (London: Verso, 2009), xx–xxi.

Schmitt’s Political Romanticism (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1986 [1925]) discusses the state as Idea and as work of art (125–7).

The installation shots I showed came from Artchronica 1 (2005).

Groys, The Communist Postscript, 34.

Dmitri Olchanski, “La Russie actuelle disparaîtra dans dix ou vingt ans,” Le Courrier de Russie (April 8–22, 2011): 3.

See Jane and Louise Wilson’s Chernobyl Project (2010–11) or Eric Lusito’s photographs in After the Wall: Traces of the Soviet Empire (Stockport, UK: Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2009).

See “S.S.,” “Oleg Vassilyev,” A-YA 2 (1980): 26–31 (with Diagonal).

“Varlam Shalamov Tikhonovich,” A-YA Literary Issue 1, 124ff.

Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, 1817.