The artistic practices of the international neo-avant-gardes of the 1960s and ’70s are often understood through the notion of the rediscovery of the figure of the artist. Experimental art from that period included happenings, performances, and other body-related practices. One would expect such expressions of subjective freedom—to the extent they were legally permitted—from artists in the totalitarian Soviet Union. But while works of this kind did indeed exist (e.g., the performances of the Dvizhenie [Movement] group, whose members took part in outdoor “Dionysian” happenings in Crimea; or Rimma and Valeri Guerlovins’s “naked” performances), they represented cases that were relatively rare and exotic—one could even say deliberately so, since, at least for the Guerlovins, the “Western” hippie aesthetic was an important part of their message. Contrary to such expectations, however, the riskier and more experimental artistic practices of Moscow Conceptualism actually represented a rediscovery of the art object, even a utopian quest for it.

In a performance by Moscow’s Gnezdo (Nest) group called An Attempt to See Oneself in the Past and Future (from the Non-Functional Art series [1977]), young artists jump up and turn around in the air in a desperate attempt to capture their own image in a moment in the past (like in a photograph), or in the future (like in a flash of intuition)—in either case, as a static image, a still. It is the dissociation of the “seeing” me from the “seen” me, or from the “me-to-be-seen,” that is at stake here. To discover the objectified part of oneself, one has to stop experiencing art in real time and instead envision it as a finite and autonomous “thing.” One has to achieve a suspension of uninterrupted temporality for the sake of the deed, of self-objectification. But the static image slips away instantly. The desire to break free turns out to be unrealizable. (The photodocumentation of the performance does not provide the sought-after image, since it is made by an external gaze.) It seems more difficult to stop the constant performance of life than to start it.

One might assume that artists behind the Iron Curtain were freer to produce material objects than to move their bodies. But in the Soviet Union of the ’70s it was the reverse, at least for artists in the unofficial scene, who found creative ways to survive in the very malleable society of late communism. Living under no pressure in terms of housing (modest housing was provided by the state), career (theirs was nonexistent), and money (almost nonexistent), they had ample time to hang out indoors and outdoors (within Soviet borders, of course) in a kind of an endless and slightly Surrealist “involuntary performance.” It is often said that the practices of Moscow Conceptualism were largely immaterial; the artists did not need to produce any work since they were constantly meeting and exchanging ideas.

This strange freedom from production was exactly what the young Gnezdo artists sought to break free from. But it was a failed liberation: in An Attempt to See Oneself in the Past and Future, the dream of self-objectification remains unfulfilled. The performative character of the action pointed to this fact, as if the very form of performance were synonymous with the failure to suspend “turning around” and to produce something.

The name of the series this performance belongs to—Non-Functional Art—might make us ask: Isn’t all art basically non-functional? But one has to remember that under Soviet communism, art was ascribed an official function, namely, to produce a New Man, a new subjectivity. Thus, the only way to de-functionalize and temporally stop the Soviet art machine was to convert it to producing non-functional autonomous objects.

This might seem bizarre to us, living as we do under contemporary capitalism. The ideas of the Moscow Conceptualists diverge radically from our mainstream critical vector. Today, finished, polished, and proudly autonomous art objects tend to antagonize the “progressive” art scene, while the production of subjectivities is seen as one of the most liberating functions of art. But this is so because after 1968, the international art scene adopted many ideas from the Russian communist avant-garde. When these ideas reached the left-wing West they seemed to have no followers in the Soviet Union itself. But Moscow art of the ’70s inhabited an upside-down world, one defined by the victory of anticapitalism rather than the victory of communism, socialism, or the Soviet regime. Today’s—partly utopian, partly routine—critical “politics of resistance” was their everyday life, the official discourse they had to negotiate; they were born into it and worked with it. It is their sober and dialectically quirky reflection on the conditions after the victory (and subsequent Thermidorian degeneration) of a social and aesthetic alternative that Moscow Conceptualism has to offer a contemporary audience. Their work is especially relevant today because we live under a capitalism that is closely entangled with its negation.

***

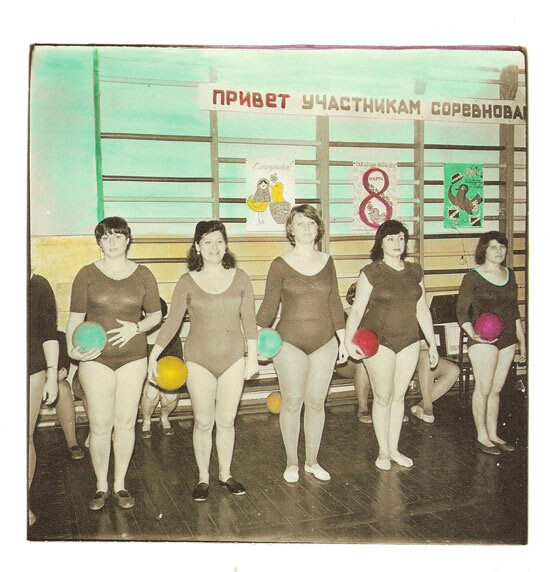

Theirs was a radical world. Moscow artists of the ’70s and ’80s lived not just outside the private market; they lived outside the traditional aesthetic categories associated with that market, including the basic subject-object opposition. The West’s “discovery” of subjectivity in the ’60s and ’70s took place amidst an abundance of objects, be they artworks or consumer goods. (To some extent this was also true in Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia.) But in the Soviet Union the memory of bourgeois life had long since been erased. Rare consumer objects existed amidst an abundance of non-reified subjectivities—including workers involved in semi-artistic activities in their leisure time—and pre-industrial everyday objects, homemade rather than bought.

One of the ambitions of the communist revolution was the abolition of unjust imbalances, not just between rich and poor, white and non-white, and man and woman, but also between subject and object. (Subject-object relations are not innocent. Indeed, they are rooted in the operations of exchange and property). The antagonism between the artist and his or her model was successfully resolved by the abolition of representation and the advent of abstract art. But an even bigger challenge was to abolish the difference between the artist and the artwork. This had to be done not just by making the artist the protagonist of a new art system based on artists’s unions rather than institutions geared toward art consumption (although this was done). It had to be done through the “re-education” of the artwork so it would acquire a “conscience,” become a non-alienated subjectivity, a “comrade-thing,” which communist theorists called for.

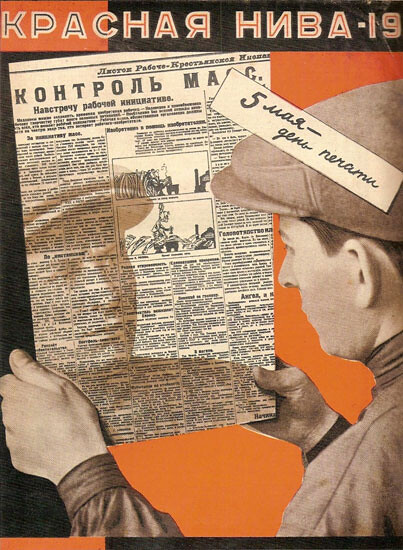

In an iconic magazine illustration by the Stenberg brothers—later used by Lissitzky and Senkin for the “Press” exhibition frieze (1928)—a man holds just such a comrade-thing: a supportive one, an (almost) free-of-chargeone, a communicative one. In this object—a newspaper—he sees his mirror reflection, his own true image. This might be read as a prophesy of the obsession with mimesis that would soon take hold of the Soviet avant-garde. Bland and boring Soviet realist painting and sculpture became the ultimate “comrade-thing”—politically aware, militant, and always there, as omnipresent as a magazine reproduction, a poster, or a monument.

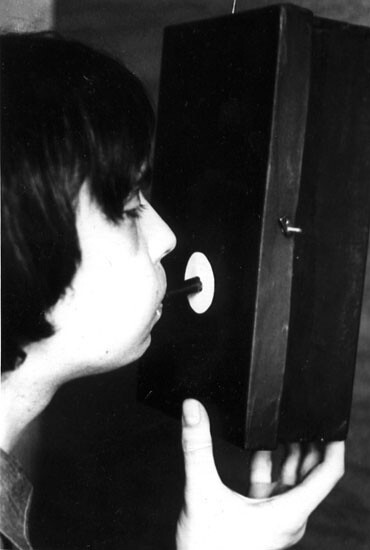

An old photograph of Andrei Monastyrski’s Finger (1978) is strangely akin to the Stenbergs’s illustration. In Finger,the artist points at himself with his own disconnected hand, thus splitting into two objectified parts. Like An Attempt to See Oneself in the Past and Future, this is a performance of self-objectification, realized with a device created for (as Monastyrski put it) “pointing to oneself as to an object external to oneself”: a box with a hole where one can insert one’s hand and extend an indicative finger. What is touched upon here—quite literally—is a painful but desired separation of the product of labor from its producer, the same alienation described by Soviet Marxist philosophy not as a universal human condition but as a symptom of commodity-money relations. Here, Monastyrski turns himself into a character in his own narrative, applying another important Moscow Conceptualist technique: the objectification the artist. This technique started with Komar and Melamid’s narrative installations about two fictitious historical artists, Apelles Ziablov and Nikolaj Buchumov. It continued in Ilya Kabakov’s famous Ten Characters series and then turned into undisguised self-objectification in Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s monumental Alternative History of Art,where a certain Ilya Kabakov is one of the fictitious characters.

But let’s also look at the object itself and other “performative objects” (or “action objects” [akzionnye objekty]), as Monastyrski called them. What does it mean for an art “thing” to be transferred to the realm of subjectivity? What kind of a status does this confer?

Strangely, Monastyrski’s humble cardboard box, which could not be more remote from the bombastic canon of Soviet painting, fully corresponds to communist aesthetics. The subjectivization of an art object changed the quality by which it was measured. Under communism, where art objects were just as subject to democracy and egalitarianism as artists, artworks were judged by their “moral” and communicative qualities, not by their beauty. In the Soviet Union the notion of universal bourgeois quality was abolished more radically than we, with our market-contaminated art scene, can scarcely achieve.

Communist artwork also challenged the idea of individual production. It usually involved a collective: in Heap (1975) Monastyrski asked anyone visiting his apartment to leave a small everyday item, until the heap reached a certain height. Communist artwork could also be, almost literally, alive and respiring: in Breathing Device (1977) Monastyrski breathed into a balloon hidden inside a box and inhaled the air it breathed back. Soviet art also constantly changed, as with Monastyrski’s enigmatic object Soft Handle (1985). During a performance by the Collective Actions group, Monastyrski secretly wound a long rope around the handle of the object, but this activity remained invisible to the other participants. This constant change was juxtaposed with the immobile clock face that was printed on the paddle to which the “soft handle” was attached.

Soviet artists also questioned longevity: if art and life were essentially the same, one had to accept the mortality of art as one accepted one’s own mortality. The original Finger, which was destroyed or lost and then reproduced several times, is in this sense no different from the paradigmatic Soviet painting or sculpture that circulated in reproductions and hand-made copies. Radical left-wing urban planners of the early 1930s (most notably Mikhail Okhitovich) envisioned Soviet constructivist buildings gradually disappearing and dissolving into their surroundings, overgrown with moss and weeds. They considered a unique building, like an art piece, to be a temporary—and necessarily limited—realization of the whole of artistic subjectivity. This kind of subjectivized object did not even need to be physically present. It could be purely narrated, as in the work of the poet, playwright, and artist Dmitri Prigov. His installations, long before they were materialized as objects in space, were described in his experimental plays of the early ’70s. In this system, an artwork was narrated or performed but not “exposed” separately from the artist and outside the time frame of the narrative or performance.

At the core of this radical dematerialization of the art object was dialectical materialism, a philosophy that called for the constant evolution of creative activity, as opposed to the production of static, finite, and fetishized objects separate from the vital process of life. This Soviet version of Marxism—which, on the political level, turned into a witch hunt against “formalism” (read: capitalist influence), especially from the ’30s–’50s—proved successful precisely because the idea of anti-formalism was already widespread among Russian artists. It fully corresponded to the ideas of the early Russian avant-garde, which understood abstraction (or “non-objective art” as they preferred to call it) as an elevation to the level of “art as such,” distanced from any concrete artwork or form. In non-objective art, there are no objects. It’s not that objects do not exist; rather, they are subjectivized.

This system is, of course, more akin to amateurish diffused “art pursuit” than to professional “art production.” That is exactly how art was perceived, taught, and promoted in the Soviet Union—as a democratic performative practice accessible to everybody (although dance and piano were privileged spheres). Recall that Kandinsky’s extremely influential (especially in Russia) innovation was to compare the artist to a composer rather than to a performer, i.e., to someone who creates a world rather than depicting it. One should not forget, however, that in this system an artist was still a performing composer, one who, like a rhapsodist, performed his own creation. In fact, independent cultural practices of Soviet art in the ’60s and ’70s tended to integrate this “compositional” element of individual authorship into the communist idea of art, while accepting the deeply rooted performative character of it. For example, there were singing poets of all kinds, and artists presented their work to friends in the form of performances (which Kabakov and Monastyrski both practiced). The practices of Moscow Conceptualism were based on this nonprofessional art experience, but also pondered its limitations, testing the grounds of alienation and reification, those unavoidable byproducts of exhibiting gesture as such.

In fact, in Monastyrski’s Finger, the optical dissection of the performer’s body (his right hand is absent from the final “objectified” image) reveals that Finger is also just a piece of art, a fragment of the whole, just one manifestation of it. For a communist artist, this venture into the territory of professional, “concrete,” and object-oriented art-making—dabbling in production—was an experiment, one no less risky than a collectivist and dematerializing escapade would have been for a Western artist of that same era.

It is not just a question of aesthetic risks. If it was politically risky for an artist under capitalism to quit the territory of safe autonomous art for a communal life, it was equally dangerous for an artist under anticapitalism to quit communal life for autonomous art-making. Boris Mikhailov, an amateur photographer in the ’60s, was often asked to document the everyday life of a sleepy research institute where he was employed. But when he isolated one snapshot from a series to print it anew and color it by hand—when he saw himself as an artist producing unique works rather than a member of a “creative” collective—he crossed a line. By creating an obvious “piece of art,” Mikhailov betrayed the collective. Unsurprisingly, he was soon fired. He went on to have a successful career as an independent artist, mostly in the West.

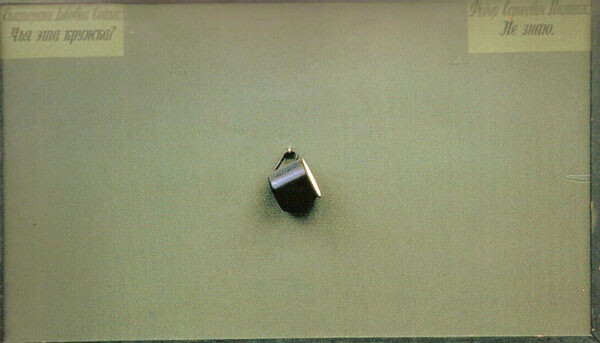

Another example of this “artistic” isolation of a single object previously entangled in communal subjectivity is Ilya Kabakov’s Kitchen Series of the ’80s. In this performance, Kabakov’s unseen characters repeatedly ask, “Who does this grinder (mug, fly) belong to?”, as if trying to grasp the notion of private property—as well as the ability to discern one fly from another.

This elevation of everyday objects to the level of art, this “transfiguration of the commonplace,” is well known in art history as the “found object” operation. But the point is not, in fact, that the wretched mug and crippled grinder glued to the surface of a greyish Masonite board are found objects. Kabakov’s atypical assemblages with only one item “assembled” also had the status of found objects, as long as they remained in his studio without any hope of being exhibited. Rather, the real theme of Kitchen Series is the very gesture of exposure, the physical and intellectual isolation of a single item. This move changes the gaze from unfocused to focused, from “found” to “sought”—a potentially commercial, career-driven, unjust, undialectical, and undemocratic operation that professional art, as practiced under capitalism, is based on.

Picasso’s famous saying about “finding rather than seeking” is profoundly undialectical from the point of view of normative communist aesthetics. A popular Soviet motto asked any citizen (ordinary citizens were considered innovative artists) “to struggle and to seek, to find and not to surrender” (not even after having found what one was seeking, presumably). Non-capitalist art had to remain on the level of the “unfound object,” “not yet formalized.” An artist was supposed to be “constantly evolving,” “searching,” and even “researching.” Any finished form with a pretense to stylishness or aesthetic aspiration was suspected of undialectical “absolutization” and “formalism,” synonymous with capitalist art. Okhitovich wrote that the straight line is deeply rooted in the principle of landed property and as such must be abolished in architecture and urban planning—but abolished in a dialectical way, so this abolition would not itself acquire purely aesthetic, “formalist” qualities.

Kabakov’s Kitchen Series is simultaneously a critique of and homage to these “dialectical objects,” be they Anna Ivanovna’s old grinder or Kabakov’s own drab board-like painting—bastards of the insane relationship between art and life.

In a series of photos connected to his text Earth Works (1987), Monastyrski strolls through nondescript urban locales (reminiscent of Robert Smithson’s Passaic). The locales seem to lack any artistic or architectural pedigree, or to half-hide it, as if illustrating Monastyrski’s thesis of “unnoticeability” or “blending,” an important notion for the objects he himself used in actions. He is not “seeking” these sites, yet he unavoidably “finds” them by taking photos of them, or by asking his fellow traveller to take photos. In one of these photos we see Monastyrski surrounded by what might, in a different context, be an assemblage of chunky minimalist sculptures. He points at the earth, at a place where a big pit (“earth works”) once existed, undisturbed by any “works” for some time. The pit intrigued him and stimulated his own practice, as he writes in the text.

What he point with is, in fact, the Soft Handle, which becomes another device of objectification—this time, the objectification of nothing. Or perhaps of the moss-covered city that Soviet urban planners dreamt about.

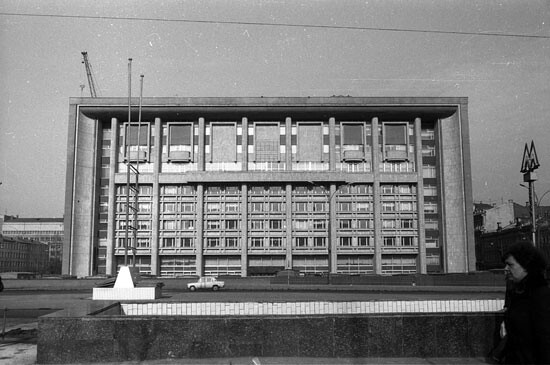

In his text for this project, Monastyrski writes that in the Soviet Union, the sphere of politics and the state created an already aestheticized and thoroughly ideological field of “life” (which he calls the “expositional field”). Artists were only able to build another layer (the “demonstrative field”) over this state-created field. In fact, some of the “non-buildings” that Monastyrski encountered and photographed during his drift could have been relics of ’60s-era neo-constructivist Soviet architecture, or even classic constructivist works built from recyclable and biodegradable materials, as Okhitovich planned to do. By pointing at them, by finding them and making them part of his own work, Monastyrski brings them to life—or, rather, out of life, to the level of art.

In his short text On Art Autonomy (1981), Monastyrski writes about an incident that occurred while he was at home reading Boris Groys’s text of the same name. While reading he heard a disturbing noise coming from outside his second-floor apartment. It was the sound of someone’s drunken vomiting. After finishing the text half an hour later, Monastyrski was surprised to notice that the vomiting persisted. Now the sound was divided into two rhythmic sets of almost identical belches. With growing astonishment, Monastyrski realized that the first set was a crow’s caw while the second was the drunkard’s howl. The drunkard’s howl had become, according to Monastyrski, purely “artistic” and deliberately mimetic.

Monastyrski writes that during the initial sequence of sounds, the drunkard was completely absorbed in his vomiting, closed off from the world and only able to relate to sounds similar to his own, through conscious or unconscious mimeticism. Then the crow, “feeling pity” for the man, gave him an example to follow and “liberated” him from his misery, saving him from complete collapse. (Here Monastyrski proves his brilliant understanding—conscious or unconscious—of Lenin’s aesthetic “theory of reflection,” which begins with the mirror-reflection of one natural phenomenon by another one.) In the groaning of the drunkard—now liberated and elevated to the level of artist—Monastyrski hears “extremely sober sounds, full of tender, almost loving gratitude to the original.”

Monastyrski makes no further mention of Boris Groys or art autonomy in the text. He never explains exactly when the drunkard achieved autonomy. Was it when the drunkard was “not yet an artist,” still an amateur in “constant evolution,” authentic in his sincere but exhausting self-expression and completely closed off from the world outside him? Or was it when he started to groan “on purpose,” when he became “a professional artist”—having mastered the laws of rhythm and composition—that he became a “formalist”?

***

It is usually thought that classic conceptual art, like classic avant-garde art, was built around the paradigm of the end of art, although we rarely use such words nowadays. The language of the death of art (“absence,” “void,” “lack,” “geometry,” “objectification,” and so forth) does not seem to work on us anymore, neither emotionally nor intellectually. We do not seem to think it genuinely expresses the idea of death, in an era when fasting is a trend and void is a style. The digital revolution further undermined the language of the death of art, making the gestures of burning and cutting harmless. But we still expect artists to know that art is dead, and to master the corresponding language of self-restraint, as if this were an indication of serious art as opposed to kitsch, of professional art as opposed to amateurism. We immediately and gratefully recognize this comatose (or “critical,” as Greenberg put it) language and instinctively dismiss art that looks unprofessionally healthy.

But art based on non-alienated, nonprofessional, free activity and dialectical wholeness, rather than on the making of “art pieces,” calls not just for different forms. It also calls for different discourses and criteria. If we truly want to resist rather than just create the pieces of resistance—the mere signs of resistance—we must reconsider our own cognitive and rhetorical apparatus.

This kind of non-alienated art is based on the notion of a future and imminent emergence of art rather than on its confirmed death. It might teach us to see not what is already there in art, but an art en devenir (and not “in progress” as we routinely say). Non-alienated art does not value irreproachable and finite artwork. It values what might become an artwork, what is in the process of becoming one, what is imperfect, what might have looked different if circumstances were otherwise, what had a chance to become art but screwed it up completely.

We can find deep humanist and democratic feeling in these artifacts that still display their hopes and possibilities (making them “embarrassingly” alive by today’s necrophilic professional standards). As Ernst Bloch wrote, “art is a laboratory and at the same time a feast of fulfilled possibilities together with … alternatives they contain.”