By way of an introduction to this issue of e-flux journal, I would like to discuss the changes in our understanding and perception of art engendered by conceptual art practices of the 1960s and 1970s, focusing not on the history of conceptual art or individual works, but rather on the ways in which the legacy of these practices remains relevant for us today.

I would argue that from today’s perspective, the biggest change that conceptualism brought about is this: after conceptualism we can no longer see art primarily as the production and exhibition of individual things—even readymades. However, this does not mean that conceptual or post-conceptual art became somehow “immaterial.” Conceptual artists shifted the emphasis of artmaking away from static, individual objects toward the presentation of new relationships in space and time. These relationships could be purely spatial, but also logical and political. They could be relationships among things, texts, and photo-documents, but could also involve performances, happenings, films, and videos—all of which were shown inside the same installation space. In other words, conceptual art can be characterized as installation art—as a shift from the exhibition space presenting individual, disconnected objects to a holistic exhibition space in which the relations between objects are the basis of the artwork.

One can say that objects and events are organized by an installation space like individual words and verbs are organized by a sentence. We all know the substantial role that the “linguistic turn” played in the emergence and development of conceptual art. Among other currents, the influence of Wittgenstein and French Structuralism on conceptual art practice was decisive. This influence of philosophy and later of so-called theory on conceptual art cannot be reduced to the substitution of textual material for visual content—nor to the legitimations of particular artworks by theoretical discourses. Rather that the installation space itself was reconceived by conceptual artists as a sentence conveying a certain meaning—in ways analogous to the use of sentences in language. Following a certain period of the dominance of a formalist understanding of art, with the appearance of conceptual art, artistic practice became meaningful and communicative again. Art began to make theoretical statements again, to communicate empirical experiences, to formulate ethical and political attitudes and to tell stories. Thus, rather than art beginning to use language, it began to be used as language—with a communicative and even educative purpose.

Of course, art was always communicative: it communicated images of the external world, the attitudes and emotions of artists, the specific cultural dispositions of its time, its own materiality and mediality and so forth. However, the communicative function of art was traditionally subjugated to its aesthetic function. Past art was judged primarily according to the criteria of beauty, sensual pleasure and aesthetic satisfaction—or calculated displeasure and aesthetic shock. Conceptual art established its practices beyond the dichotomy of aesthetics and anti-aesthetics—beyond sensual pleasure and sensual shock. This does not mean that conceptual art ignored the notion of form and concentrated itself exclusively upon content and meaning. But a reflection on form does not necessarily mean the subjugation let alone the obliteration of the content. We can speak about the elegant formulation of an idea—but by doing so we mean precisely that this formulation helps the idea to find an adequate and persuasive linguistic or visual presentation. On the contrary, a formulation that is so brilliant that it obliterates the idea is experienced by us not as beautiful but as clumsy. That is why conceptual art prefers clear, sober, minimalist forms—such forms better serve the communication of ideas. Conceptual art is interested in the problem of form not from the traditional perspective of aesthetics but from the perspective of poetics and rhetoric.

It makes sense to reflect for a moment upon this shift from aesthetics to poetics and rhetoric. The aesthetic attitude is basically that of the spectator. Aesthetics as a philosophical tradition and a university discipline relates to art and reflects upon art from the perspective of the art spectator—or one could also say from the perspective of the art consumer. Spectators mostly expect an aesthetic experience from art. Since the time of Kant, we know that this experience can be one of beauty or of the sublime. It can be an experience of sensual pleasure. But it can also be an anti-aesthetic experience of displeasure, or of frustration provoked by an artwork that lacks all the qualities which an affirmative aesthetics expects it to possess. It can be the experience of a utopian vision that could lead away from present conditions to a new society in which beauty reigns. Or, to formulate this differently, it could be a redistribution of the sensible, one that refigures the spectator’s terms of vision by showing certain things and giving access to certain voices that were previously concealed or obscured. But, because the commercialization of art already undermines any possible utopian perspective, it can also be a demonstration of the impossibility of positive aesthetic experience within a society based on oppression and exploitation. As we know, these seemingly contradictory aesthetic experiences can be equally enjoyable. However, to experience aesthetic enjoyment of any kind, a spectator has to be aesthetically educated. This education necessarily reflects the social and cultural milieus into which the spectator was born and in which he or she lives. In other words, an aesthetic attitude presupposes the subordination of art production to art consumption—and likewise, the subordination of artistic theory and practice to a sociological perspective.

Indeed, from the aesthetic point of view, the artist is a supplier of aesthetic experiences, including those produced with the goal to frustrate or modify the viewer’s aesthetic sensibility. The subject of the aesthetic attitude is the master—the artist is the servant. Of course, the servant can and does manipulate the master, as Hegel convincingly demonstrated in his Phenomenology of the Spirit, but nevertheless, the servant remains the servant. This situation did not change much when the artist became a servant to the public at large, instead of being a servant under the patronage regimes of the Church or traditional autocratic powers. In previous periods, the artist was obliged to present “contents,” for example subjects, motives, narratives and so forth, that were dictated by religious faith or the interests of political power. Today, the artist is required to treat topics of public interest. Just as the Church and autocratic powers of yesteryear wanted their beliefs and interests to be represented by the artist, so today’s democratic public wants to find in art representations of the issues, topics, political controversies and social aspirations by which it is moved in everyday life. The politicization of art is often seen as an antidote to the purely aesthetic attitude that allegedly requires art to be merely beautiful. But in fact, the politicization of art can be easily combined with its aesthetic function—as far as both are seen from the perspective of the spectator, of the consumer. Clement Greenberg remarked long ago that an artist is best able to demonstrate his or her mastery and taste when the content of the artwork is prescribed by an external authority. Being liberated from the question “What should I do?” the artist can concentrate on the purely formal side of art—on the question “How should I do it?” This means: “How should I do it in such a way that certain contents become attractive and appealing (or maybe non-attractive, repulsive) to the aesthetic sensibilities of the public?” If the politicization of art is interpreted as “making certain political attitudes attractive (or maybe unattractive) for the public”—as is usually the case—then the politicization of art becomes completely subjected to aesthetic attitude. At the end, the goal becomes the packaging of certain political contents in an aesthetically attractive form. But aesthetic form loses its relevance in any act of real political engagement—and is discarded in the name of direct political practice. Then art functions as a political advertisement that becomes superfluous once it has achieved its goal.

In fact, this is only one of many examples that demonstrate why an aesthetic attitude becomes problematic if applied to the arts. Actually the aesthetic attitude does not need art—and functions much better without it. It is an old truism that all the wonders of art pale in comparison with the wonders of nature. In terms of aesthetic experience, no work of art can bear comparison with an even average sunset. And of course, the sublime aspects of nature and politics can only be fully experienced by witnessing a natural catastrophe, revolution or war—not by reading a novel or looking at a picture. This was the opinion shared by Kant and the Romantics who launched modern aesthetic discourse. The real world, they claimed, is the legitimate object of an aesthetic attitude (as well as of scientific and ethical attitudes)—not art. According to Kant, an artwork can become a legitimate object of aesthetic contemplation only as a work of genius, e.g. only as a manifestation of natural force operating unconsciously in and through man. Fine art can serve only as a preliminary means of education in taste and aesthetic judgment. After this education is completed, art, like Wittgenstein’s ladder, can be thrown away—to confront the subject with the aesthetic experience of life itself. Seen from an aesthetic perspective, art reveals itself as something that can and should be overcome. All things can be seen from an aesthetic perspective; all things can serve as sources of aesthetic experience and become objects of aesthetic judgment. From the perspective of aesthetics, art has no privileged position. Rather, art is something that posits itself between the subject of the aesthetic attitude and the world. However, the mature subject does not need any aesthetic tutelage via art—being able to rely on personal sensibility and taste. Aesthetic discourse, if used to legitimize art, de facto undermines it.

How, then, should one explain the fact that the discourse of aesthetics acquired such a dominant position during the period of modernity? The main reason for this is a statistical one. Artists were a social minority during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the founding period of aesthetic discourse—and spectators were in the majority. The question of why one might make art seemed irrelevant—artists made art to earn their living. This seemed an adequate explanation for the existence of the arts. The problem was why other people should look at art. The answer was: to form their taste and develop their aesthetic sensibility. Art was a school for the gaze and other senses. The social division between artists and spectators seemed to be firmly established: spectators were subjects of an aesthetic attitude—artworks produced by artists were objects of aesthetic contemplation. But from the beginning of the twentieth century, this simple dichotomy began to collapse.

Today, contemporary networks of communication like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter offer global populations the possibility of presenting their photos, videos and texts juxtaposed in ways that cannot be distinguished from those of many post-conceptualist artworks. The visual grammar of a website is not too different from the grammar of an installation space. Through the internet, conceptual art today has become a mass cultural practice. Walter Benjamin famously remarked that the masses easily accepted montage in film—even if they had difficulties accepting collage in Cubist paintings. The new medium of film made artistic devices acceptable that remained problematic in the old medium of painting. The same can be said for conceptual art: even people having difficulties accepting conceptual and post-conceptual installation art, have no difficulties in using the internet.

But is it legitimate to characterize self-presentation on the internet, involving hundreds of millions of people all around the world, as an artistic practice?

Conceptual art can be also characterized as an art that repeatedly asked the question “what is art?” Art and Language, Marcel Broodthaers, Joseph Beuys and many others that we tend to situate today inside the frame of an expanded conceptualism asked and answered this question in very different ways. One can also ask this question from an aesthetic perspective. What now would we be ready to identify as art, and under which conditions; what kinds of objects do we recognize as artworks and what kinds of spaces are recognized by us as art spaces? But we could abandon this passive, contemplative attitude and ask a different question: what does it mean to become actively involved in art? Or in other words, what does it mean to become an artist?

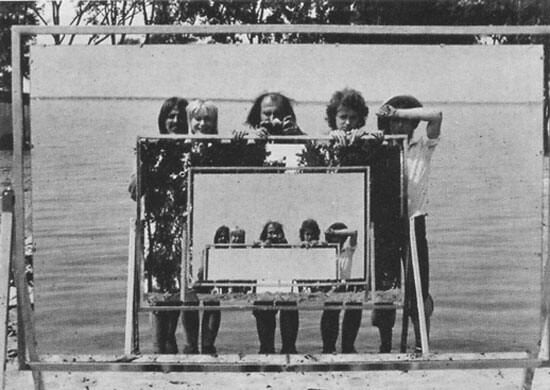

Speaking in Hegelian terms, the traditional aesthetic attitude remains situated on the level of consciousness—on the level of our ability to see and appreciate the world aesthetically. But this attitude does not reach the level of self-consciousness. In his Phenomenology of the Spirit, Hegel points out that self-consciousness does not emerge as an effect of passive self-observation. We become aware of our own existence, our own subjectivity, when we are endangered by another subjectivity—through struggle, in conflict, in the situation of existential risk taking that could lead to death. Now, analogously, we can speak of an “aesthetic self-consciousness” that emerges, not when we look at a world populated by others, but when we begin to reflect upon our own exposure to the gaze of others. Artistic, poetic, rhetorical practice is none other than self-presentation to the gaze of the other, presupposing danger, conflict and risk of failure.

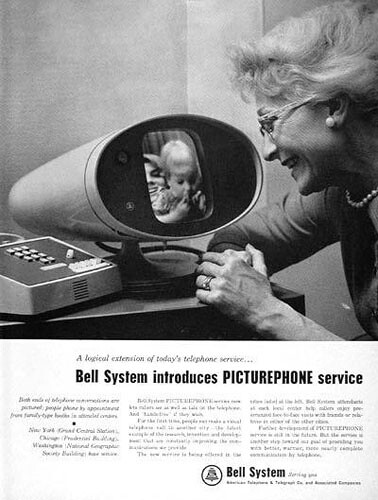

The feeling of almost permanent exposure to the gaze of the other is a very modern one, famously described by Michel Foucault as an effect of being under the panoptical observation of an external power. Throughout the twentieth century, an ever growing number of humans became objects of surveillance to a degree that was unthinkable at any earlier period of history. And practices of omnipresent, panoptical surveillance are increasing in our time at an even greater pace—the internet becoming the central medium of this surveillance. At the same time, the emergence and rapid development of global networks of visual media are creating a new global agora for self-presentation, political discussions and actions.

Political discussions in the ancient Greek agora presupposed the immediate living presence and visibility of its participants. Today everyone has to establish their own image, their own visible persona in the context of global visual media. We’re not just talking about the game “Second Life:” now everyone has to create a virtual avatar, an artificial double to begin to communicate and to act. The “First Life” of contemporary media function in the same way. Everyone who wants to go public, to begin to act in today’s international political agora has to create an individualized public persona. This requirement is relevant not only for the political and cultural elites. Today, more people are getting involved in active image production than in passive image contemplation.

This autopoietic practice can be easily be interpreted as a kind of commercial image making, brand development or trend-setting. There is no doubt that any public persona is also a commodity—and every gesture of going public serves the interests of numerous profiteers and potential shareholders. Following this line of argument, it’s easy to perceive any autopoietic gesture as a gesture of self-commodification—and, accordingly, to start a critique of autopoietic practice as a cover operation that is designed to conceal the social ambitions and economic interests of its protagonist. However the emergence of an aesthetic self-consciousness and autopoietic self-presentation is originally a reaction—a necessarily polemical and political reaction against the image that others, society, power have always already made of us. Every public persona is created primarily within a political battle and for this battle—for attack and protection, as sword and shield at the same time. Obviously, artists were always already professionals of self-exposure. But today the general population is also becoming more and more aesthetically self-conscious and getting more and more involved in this autopoietic practice.

Our contemporaneity is often characterized by the vague notion of an “aestheticization of life.” The commonplace usage of this notion is problematic in many ways. It suggests an attitude of aesthetic passivivity toward our society of the spectacle. But who is the subject of this attitude? Who is the spectator of the society of spectacle? It is not an artist—because the artist practices polemical self-presentation. It is not the masses because they are also involved—consciously or unconsciously—in autopoietic practices and have no time for pure contemplation. Such a subject could be only God—or a theoretician who took a divine position of pure contemplation after God was proclaimed dead. The notion of aesthetic self-consciousness and poetic, artistic practice must now be be secularized, purified of any theological overtones. Every act of aestheticization has its author. We always can and should ask the question: who aestheticizes—and to what purpose? The aesthetic field is not a space of peaceful contemplation—but a battlefield on which gazes clash and fight. The notion of the “aestheticization of life” suggests the subjugation of life under a certain form. But as I’ve already suggested, conceptual art taught us to see form as a poetic instrument of communication rather than an object of contemplation.

So what is constituted and communicated in and through the artwork? It is not any objective, impersonal knowledge as constituted and communicated by science. In art subjectivity comes to self-awareness through self-exposure and communicates itself. That is why the figure of the artist manifests the inner contradictions of modern subjectivation in a paradigmatic way. Indeed, the transition from the divine gaze to surveillance by secular powers has produced a set of contradictory desires and aspirations within the heart of modern subjects. Modern societies are haunted by visions of total control and exposure—anti-utopian visions of an Orwellian type. Accordingly, modern subjects try to protect their bodies from total exposure and defend their privacy against the danger of this totalitarian surveillance. Subjects operating in socio-political space struggle permanently for their right of privacy—the right to keep their bodies hidden. On the other hand, even the most panoptical and total exposure to secular power is still less total than the exposure to the divine gaze. In Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra the proclamation of the “death of God” is followed by a long lamentation about the loss of this spectator of our souls. If modern exposure seems excessive, it also seems insufficient. Of course, our culture makes great efforts to compensate for the loss of the divine spectator. But this compensation remains only partial. Every system of surveillance is too selective, it overlooks most of the things that it is supposed to see. Beyond that, the images that accumulate in such a system are mostly not really seen, analyzed or interpreted. The bureaucratic forms that register our identities are too primitive to produce interesting subjectivities. Accordingly, we remain only partially subjectified.

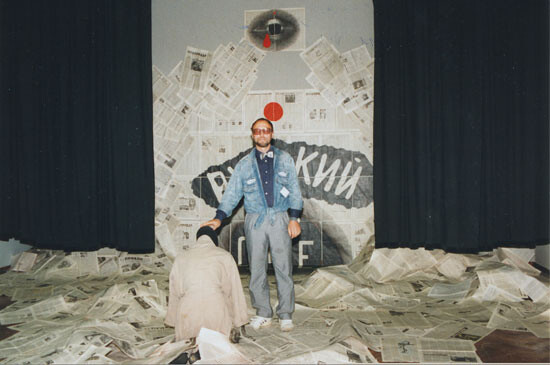

This condition of partial subjectivation engenders within us two contradictory aspirations: we are interested in retaining privacy, the reduction of surveillance, and the right to obscurity for our bodies and desires, but at the same time we aspire to a radicalized exposure that transgresses the limits of social control. I would argue that it is this radicalized subjectivation through acute self-exposure that is practiced by contemporary art. In this way exposure and subjectivation cease to be means of social control. Instead, self-exposure presupposes some degree of sovereignty over one’s own process of subjectivation. The arts of modernity have shown us different techniques of self-exposure, ones that exceed the usual practices of surveillance. They contain more self-discipline than is socially necessary (Malevich, Mondrian, American minimalism); more confessions of the hidden, ugly, or the obscure than are sought by the public. But contemporary art confronts us with even more numerous and nuanced strategies of self-subjectivation, which of internal necessity situate the artist in a contemporary political field. These strategies include not only different forms of political engagement but also all the possible manifestations of private hesitation, uncertainty and even despair that usually remain hidden beneath the public personae of standard political protagonists. A belief in the social role of the artist is combined here with a deep skepticism concerning the effectiveness of that role. This erasure of the line dividing public commitment from personal vicissitudes has become an important element of contemporary art practice. Here again the private becomes public—without any external pressure and/or enhanced surveillance.

Among other things, this means that art should not be theorized in sociological terms. Reference to the naturally given, hidden, invisible subjectivity of the artist should not be substituted by reference to his or her socially constructed identity—even if artistic practice is understood as the deconstruction of this identity. The subjectivity and identity of the artist do not precede artistic practice: they are the results and the products of this practice. Of course, self-subjectivation is a not a fully autonomous process. Rather, it depends on many factors, one of them being the expectations of the public. The public also knows that the social exposure of human bodies can be only partial, and therefore unreliable and untrustworthy. That is why the public expects the artist to produce radicalized visibility and self-exposure. Thus, the artistic strategy of self-exposure never begins at a zero point. The artist has to take into consideration from the outset his or her already existing exposure to the public. However, the same human body can be submitted to very different processes of socially determined subjectivation, depending on the particular cultural contexts in which this body may become visualized. Every contemporary cultural migrant—and the international art scene is full of migrating artists, curators, art writers—has innumerable chances to experience how his or her body is situated and subjectified in and though different cultural, ethnic and political contexts.

But if so many people all around the world are involved in autopoietic activities why should we still speak about art as a specific practice? As I’ve already said, the emergence of the internet as the dominant medium of self-presentation seems to lead us to the conclusion that we don’t need any more institutional art spaces to produce art. And over the last two decades, institutional and private art spaces have been subject to a massive critique. This critique is completely legitimate. But one should not forget that the internet is also a space controlled primarily by corporate interests—not a celebrated space of anonymous and individual freedom as was often claimed in its early days. The standard internet user is, as a rule, concentrated on the computer screen and overlooks the corporate hardware of the internet—all those monitors, terminals and cables that inscribe it into contemporary industrial civilization. That is why the internet has conjured for some the dreamlike notions of immaterial work and the general intellect within a post-Fordist condition. But these are software notions. The reality of the internet is its hardware.

A traditional installation space offers a particularly appropriate arena to show the connectivity to hardware that is regularly overlooked during standard internet use.

As a computer user, one is immersed in solitary communication with the medium; one falls into a state of self-oblivion, potentially unaware of one’s own body. The purpose served by an installation that offers visitors an opportunity to make public use of computers and the internet now becomes apparent. One no longer concentrates upon a solitary screen but wanders from one screen to the next, from one computer installation to another. The itinerary performed by the viewer within the exhibition space undermines the traditional isolation of the internet user. At the same time, an exhibition utilizing the web and other digital media renders visible the material, physical side of these media—their hardware, the stuff from which they are made. All of the machinery that enters the visitor’s field of vision thus destroys the illusion that everything of any importance in the digital realm only takes place onscreen. More importantly, however, other visitors will stray into the viewer’s visual field. In this way the visitor becomes aware that he or she is also being observed by the others.

Thus one can say that neither the internet, nor institutional art spaces can be seen as privileged spaces of autopoietic self-presentation. But at the same time these spaces—among many others—can be used by an artist for his and her goals. Indeed, contemporary artists increasingly want to operate not so much inside specific art milieus and spaces but rather on the global political and social stage—proclaiming and pursuing certain political and social goals. At the same time they remain artists. What does this problematic title mean, within the extended, globalized, social-political context? One can perceive the title “artist” as a stigma that makes any political claim suspicious and any political activity inefficient—because inescapably co-opted by the art system. However, failures, uncertainties and frustrations are not the sole privilege of artists. Professional politicians and activists experience them to the same, if not to a greater degree. The only difference is this: professional politicians and activists conceal their frustrations and uncertainties behind their public personae. And accordingly, the failed political action remains final and unredeemed within political reality itself. But a failed political action can be a good work of art because it reveals the subjectivities operating behind this action even better than its possible success. By assuming the title “artist,” the subject of this action signals from the beginning that he or she aims at self-exposure rather than the self-concealment that is usual and even necessary in professional politics. Such self-exposure is bad politics but good art—herein lies the ultimate difference between artistic and non-artistic types of practice.