Globalism in its Mobilized Form

Mobility in architecture means to mobilize—money, above all—on behalf of the immobile: to build more space in less time. This further confirms what theorists of the early twentieth century first recognized as modernity’s triumph of space over time, what Michel Foucault would later call the modern obsession with space. While the nineteenth century was preoccupied with time, evolution, cycles, and halt, the twentieth century was concerned with space—so much so that time became but one possible representation of a distribution of elements in space.1

If we interpret globalization as a type of mobilization, we take notice of this process in the rapid pace of architectural expansion in Asia. According to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, six of the world’s fifteen tallest buildings are located in China, while three are in the United States.2 Newly published research predicts that for the next three years, China will construct a new skyscraper every five days.3 Today, the relation between space and time is that of mobilization: the amount of space built is inversely proportional to the time it takes to build. Exceptions are rare and expensive.

Mobilization is to the immobile what the internet is to the architect (who actually sits in an immobile position in front of the screen): a global reality—or what is taken as such—that is delivered more or less free on demand, as the French writer Paul Valéry (1871–1945) anticipated in a text titled “The Conquest of Ubiquity.”4 In this essay from the 1930s he reflects on art and architecture as subject to the vast transformations of modern times: possibilities and potentials have become numerous, malleable, and accurate enough that the age-old handling of beauty is deeply affected. In allusion to modern physics, Valéry explains that in all of the arts there is a field subordinate to the laws of nature that cannot be regarded or treated as it was prior to modernity. Matter, space, and time are not what they used to be, and their reincarnations affect all sorts of techniques and technical processes. This has transformed the ways artworks are transmitted and reproduced, making them ubiquitous—not only do artworks exist in themselves, they can also be recreated wherever the appropriate apparatus is available. Mobilization takes command.

Valéry is renowned not only for his lyrics and prose, but also for his monumental notebooks, in which he transformed literary work into scientific research. The modern mind—which for Valéry means the intellect originating in the sciences—is universally interested, above all, in mathematics and physics. Yet, it is a mind genuinely concerned with the transformations and great conflicts of the twentieth century. Valéry actually recognizes the dynamics, divisions, and fragmentations of a world whose unity has been lost forever. Following in the steps of Friedrich Nietzsche, he watches reality enter the era of complexities and pluralities, or—to use his own term—the era of multiplicities. In this, the integral vision of the world turns out to be obsolete, and can only be compensated by multiple observations from multiple perspectives. Above all, Valéry is worried about mobilization in all fields of modern life, with economic exchange value becoming a universal model. In this vein, Monsieur Teste, the eponymous figure of Valéry’s renowned novel, reports:

I was seeing in my mind the market, the stock exchange, the Occidental bazaars for the exchange of phantasms. I was occupied with the wonders of the transitory, and its astonishing duration, with the force of paradox, with the resistance of worn-out things. … Everything appeared in images. Abstract struggles took the form of a sorcery of devils. Fashion and eternity collared each other. The retrograde and the advanced were contesting at what point to occur. Novelties, even new ones, were giving birth to very old consequences. What silence had elaborated was cried for sale. … In short, all possible spiritual events passed rapidly before my soul that was still half asleep. Still limp and confused, it was seized with terror, disgust, despair, and frightful curiosity, contemplating the ideal spectacle of this immense activity called intellectual.5

For Valéry, modernity means that all activities, thoughts, and imaginations become part of an economy based on the exchange of values. As such, they participate in extreme forms of mobility, instability, and arbitrary pricing; paradox and spectacle are common features of this novel dynamic. For this economy, Valéry adopts the language of the stock market to describe the instant disposal of all values, whether mental, political, or aesthetic. Spiritual values take the biggest hit:

I have just said “value” and I say that there is a value called “mind,” just as there is an oil value, wheat value, or gold value. I have said value, because there is appreciation, judgment of importance, and because there is a discussion of price, which we are prepared to pay for this value: mind. … All of these rising and falling values constitute the grand market of human affairs. Among them, the unfortunate value of mind does not cease to fall.6

It is no longer contents, essences, or significations that are of interest, but rather their movements and fluctuations. They are valuable only in relation to difference, and are therefore volatile. They are also mobilized, because they are subject to temporal, unstable, and contingent determinations that are cancelled as soon as they are fixed.

Valéry finds this frenzy of speed destructive for human thinking and feeling. He describes people moving so fast they deny themselves thought and delight. The skyscrapers of Manhattan may impress the world, but the huge buildings are only to be viewed at a speed of 120 kilometers per hour. Seen from the ground, an hour would be much too long to study them. To Valéry’s nostalgic eyes, the skyscraper’s scale has replaced true efficacies, the spectacle has superseded concerns of usefulness, beautiful ideals have been abandoned for the allure of the new, and the pursuit of attention has destroyed continuity. Modern spectacle has replaced the classic order.7

Eupalinos: Slowing Down

For Valéry, the problem is not merely the loss of the classical formal language in architecture. He is himself too modern for that kind of conservative argumentation. Rather, it is the concept of architecture as a unifying, meaningful, and binding form that to him seems in crisis.8 Valéry brings Socrates and Phaedrus together out of Hades to discuss an imaginary recollection of architectural form—arguably a vision of a modern aesthetics halting the mobilized world through timeless beauty. Eupalinos is the name of this Platonic dialogue, after the ancient Greek architect who, according to Phaedrus, had the great ability to put things in order. Under his direction, formless stacks of stones were organized into the most beautiful architecture. By connecting the regular and the irregular, Eupalinos could create clear and organized forms and immersive space. Inside this quasi-total work, humans could move around and feel their presence in the world, either in silence or with a pleasant murmur.9 Inside Eupalinos’s buildings, people could even find sublimation without effort. As he told Phaedrus in conversation, Eupalinos believed that, in realizing architecture, he built himself.

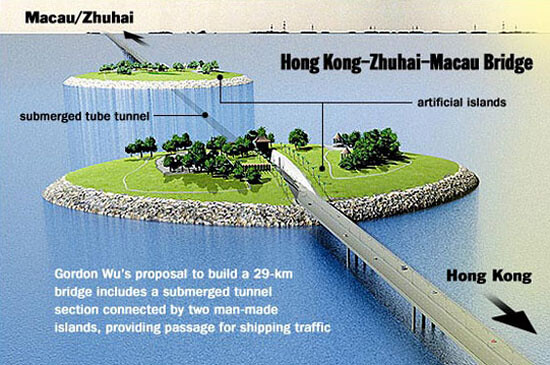

Phaedrus reports that this great architect—actually a Greek engineer who built a huge tunnel in the sixth century BC—differentiated between buildings that were mute, those that talked, and those that could sing. The mute can only be despised for their arbitrary, if sometimes pleasant forms. Those buildings content to talk Eupalinos identifies with prisons, which allow their prisoners to sigh, with department stores that provide inviting halls, readily accessible stairs, and bright, roomy spaces for businessmen, and with courthouses, whose huge masses of stone, plain walls, and few entrances can accommodate the verdicts and punishments of justice in all its majesty and rigor. Finally, Eupalinos unfolds to Phaedrus the magnificent image of the huge—singing—buildings that could be admired at the harbors.10 Their pure white wings reached out into the sea to protect the basins. Such a project, Eupalinos explains, meant to dare Neptune himself. Mountains had to be dismantled and poured into the waters that were to be enclosed; boulders had to be laid against the moving depth of the sea. Thus, the buildings created broad and still harbors of spiritual clarity that even gained in force through the contingent nature surrounding them. They were beautifully necessary and pure like musical tones. According to Eupalinos, singing buildings were harmonious in that they included the human body in their own system. They reflected human organic balance in its perfect proportions, and thereby became an instrument of life. As these balanced buildings discovered their position between body and mind, they exhibited their true relations.11

Of course, clever Socrates was able to translate what had been said in terms of architecture into something that, despite its ancient language, turns out to be the prototype of a modern aesthetics of immersion. While painting and sculpture, he argues, can only create surfaces and partial impressions, architecture realizes a composed, three-dimensional space. In this encompassing, stable, and lasting space of architecture, Socrates recognized the possibility of a total human work. In contrast to a restless nature that constantly dissolves, ruins, and overturns what it has produced, architecture is immobile and resists volatility. It is durable in confronting the continuous change and chaotic confusion of life, above all modern life. As the space of architecture is stable and enduring, movement becomes the spiritual movement of a mind that is able to negotiate the metaphysics of both Heraclitus and Parmenides.

For Valéry, what the human mind moves is the architectural composure of the stable harbor in contrast to the ever-moving waves of the sea. For the French poet, who was born in Sète on the Mediterranean Coast of France, it is in the timeless values and purity of unchangeable harmony that stem, as in music, from mathematical proportion—a universal system of ratio and scale that can be traced back to ancient Greek culture—that the human recognizes the resonance of his or her own nature. Here humans become aware of architecture as a meaningful work that stands against a mobilized modern life, lost in translation, as James Merrill’s famous poem would have it:

These days which, like yourself,

Seem empty and effaced

Have avid roots that delve

To work deep in the waste.12

For Valéry, Manhattan skyscrapers were wasteful forms of economic, sociopolitical, and aesthetic mobilization in contrast with durable architecture. As products of the global economy of exchange, they are no more and no less enormous and rapid than the whole of the crisis called modernity.

The Duck: Speeding Up

Valéry’s intellectual approach to and critical comment on modern architecture was validated by the prevalence of functionalism in the global building industry thirty years later. Within architecture there emerged a critical, late-modern movement that again called for an architecture confronting mobilized life. However, this movement did so not by generating architecture as immersive and durable space, but by generating architecture for mobile life (e.g., a highway sign). Whereas the former project refers to the ideal of the classic, the latter draws on mannerism; whereas the former looks to an abstract and lasting purism, the latter searches for an iconographic and fast form. Nevertheless, their observations converge in the present time: in the introduction to his 2004 book, Architecture as Signs and Systems for a Mannerist Time, the US architect and writer Robert Venturi writes, “In this era when change and audacity have become ends in and for themselves, epiphanies in architecture worry me as much as vision in architecture.”13

Not too far from Valéry, Venturi locates the crisis of modern architecture in an increasingly mobilized world. Yet, it is not the form of the skyscraper that signifies this crisis, but rather the global spread in the 1960s of the modern formal language. With Denise Scott Brown, Venturi sets up a program against the congealed heroic era of reductionist white modernity. They recognize that an important aspect of architecture has been lost or excluded since the end of the nineteenth century: its communicative function, its singing. They draw different consequences than Valéry, however: against the ideal of harmonization, they plead for complexity and contradiction in architecture and for a literal dialogue between architecture and humans, not in terms of Valérian immersion in an ideal space, but as communication between billboards, emblems, and typography installed as facades and entrances.

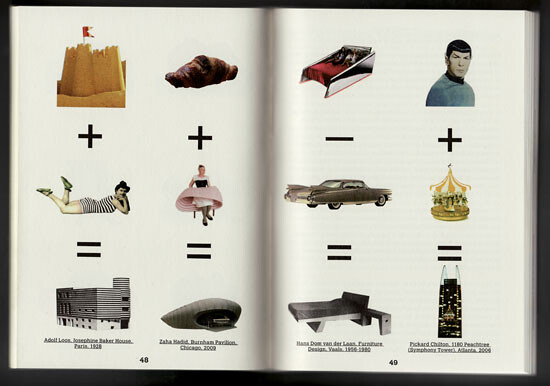

For these forms they import the aesthetics of the American vernacular and commercial culture in order to produce gestural messages that can be understood by all Americans. These are significant not in terms of space, but in terms of decorum, or “signage,” as Venturi calls it.14 In the style of a manifesto, he calls for an architecture of the information age, one that favors the iconographic surface over the architectural form, aims at explicit communication rather than artistic expression, and exhibits mannerist multimedia (in order to accommodate multiculturalism) as opposed to abstract purity.15 Similar to pop art, Venturi’s architecture does not assume the visitors or inhabitants to be naïve users, but rather attempts to integrate them in a “participatory” architectural dialogue that refers to different realities—to the historical reality of architectural forms, and to the quotidian reality of US commercial and vernacular culture. “So here is complexity and contradiction as mannerism, or mannerism as the complexity and contradiction of today—in either case, today it’s mannerism, not Modernism.”16

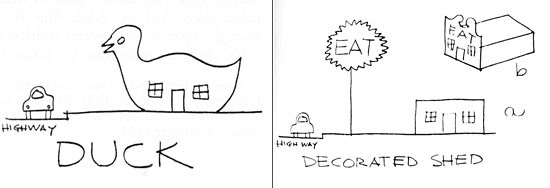

As Venturi notes elsewhere, this version of mannerism has studied the electric signs of the Las Vegas strip, the valid chaos of Tokyo, and Buddhist complexity. In all of these examples, architectural culture can discover ambiguity’s capacity for producing architecture that communicates, or sings (jazz). But singing is no longer associated with the eternal harmony and stable proportions of white architecture; instead, it refers to a car-driving American culture. While Valéry blamed the skyscrapers of Manhattan for being too fast in terms of communication, Venturi looks to buildings that are fast enough for contemporary communication. He introduces two types of buildings to illustrate the difference. The first—the Valérian type, we could say—is a system that integrates space, structure, and light in an all-architectural symbolic form called the “duck” (after an exemplary building of a grilled chicken restaurant), while the second building is called the “decorated shed.” Favored by Venturi, the two-part system of the decorated shed splits functional space from the symbolic facade and generates a rhetorical front in contrast to a conventional behind.17 Meaning in the decorated shed is captured in a sign on the front, the roof, or wherever it can be easily viewed. The building behind can be anything from a church to a restaurant, depending on the sign installed. While the duck—as the model of classical modernism—cannot keep up with the speed of modern mobility, the decorated shed utilizes a changeable and flexible environmental decoration that corresponds to contemporary culture and economy.

Venturi’s ideal decoration acts as a backdrop, or better, like a screen. The facade covers the shed behind it using signs from both high and low culture. While such a mixed catalogue of signs forsakes Valérian pillars of completeness, proportion, and unity in favor of complexity, contradiction, and paradox, Venturi nevertheless maintains a concept of architecture as a monumental built structure. Although he calls for a less elitist and more popular architectural culture, Venturi’s approach has since been regarded as more of an artistic strategy than an effective appeal for a more human architectural practice. The architecture of the past few decades has signaled a return to where we started: the Asian competition of building bigger and faster—the Valérian parallel of the stock market and cultural life, as sketched above, has regained actuality. Since the end of the Bretton Woods system and the gold standard in 1971, currencies have been free to float. With that freedom, buildings have become real-estate investment. Today, skyscrapers are designed to be viewed not at 120, but at 500 kilometers per hour from an airplane. Whether or not they sing is of little importance, because they are too distant to be heard. Furthermore, they are less products of an architectural culture of late capitalism than they are the products of a few major capitalist players. That these players do not even come to architectural play in the face of economic concerns, has been observed: architecture within architectural practice is vanishing. Design occupies only five percent of a contemporary architect’s time, with the rest dedicated to calculations, meetings, presentations, and administration. When it comes to building, architects play a marginal role, while the primary roles are occupied by corporate actors, clients, and building firms, which send even early designs through value-engineering software in order to meet projected budgets and commercial interests. Jay Merrick discusses the death of architecture in the following way:

Architects serve commercial forces that are generally uninterested in the complex cultural qualities of place, aesthetics, and history—and our planning system struggles to cope with the tensions, and the bad architecture, generated by this situation. From design to delivery, architecture is being corporatized and re-calibrated as part of sophisticated management systems. Architects are increasingly seen as service-industry operatives and it cannot be long before student architects’ reading lists include tomes on the management and production structures of exemplars of global corporate efficiency such as Toyota, Walmart, and Tesco.18

Conceptualism Realized

We could continue to complain. But we could also recognize that different, albeit smaller, forms of architecture have emerged to confront mobilized global culture. These (re-)emergent alternative architectures at least pose the crucial question: Where can architecture be located today when it is of no interest to big building projects? These are varieties of conceptual architecture that—with reference to conceptual art and architecture of the 1960s—question the traditional notion of architecture as building-construction, as master plan, or as conventional cubature. Recent conceptual works focus on design as a process that begins with an idea, passes through experiments, and results in forms that are not buildings per se. Such works are interested in intellectual and systematic approaches that bring architectural matters—typology, context, form, and so forth—to a head. They react against mobilized culture by demanding a higher degree of activity and engagement from visitors, passersby, and inhabitants than from paying users; they ask for a degree of mental mobility.

The materials of the new conceptual architectures are most often light, ephemeral, cheap, and unpretentious.19 In contrast to the famous architectural works of the 1960s and 70s, today’s architectural conceptualism does not define itself in terms of unrealized utopian plans, visualizations, or renderings of big buildings, but instead poses essential questions concerning the foundations of architecture, seeking answers on a smaller scale: in installations, pavilions, window displays, exhibitions, and magazines—what we might call micro-architecture. Such are the influences of conceptual art in contemporary conceptual architecture. (As Lucy Lippard famously commented, “The difficulty of abstract conceptual art lies not in the idea but in finding the means of expressing that idea so that it is immediately apparent to the spectator.”20) Above all, recent conceptual architecture includes works that are self-referential—not only do they question the discipline, they also reflect on the role of the architect-author. Conceptual architects do not seek legitimacy in supposedly objective values like function, need, or technology. As authors, they posit their subjective perspectives as vulnerable yet pivotal points in the design process.

If we return to the question of mobilized global culture, we recognize that conceptual architecture might be capable of providing an answer. On the one hand, it seems to embrace mobility as it literally distances itself from the classical immovable, while on the other hand, in its conceptual approach it turns mobility into a novel form of locality—not so much as geographic locality, but as authorial locality. Locality here becomes a quality of production, with local viewpoints and “local values”—in contrast to the Valérian approach—cultivating an awareness of the temporal and contingent nature of every kind of work done within an increasingly mobilized culture.

Michel Foucault, “Andere Räume,” in Aisthesis, ed. Karlheinz Barck (Leipzig: Wahrnehmung heute, 1990.

See →. See also Peter Sloterdijk, Im Innenraum des Kapitals (Franfurt: M. Suhrkamp, 2005).

See →.

Paul Valéry, Über Kunst (Franfurt: M. Suhrkamp, 1959), 46.

Paul Valéry, Monsieur Teste (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1948), 58.

Paul Valéry, “Liberté de l’Esprit,” in Regards sur le monde actuel (Paris: Delamain et Boutelleau, 1931), 264.

Vaéry, Über Kunst, 148.

Ibid., 58.

Paul Valéry, Eupalinos oder der Architekt, trans. Rainer Maria Rilke (Frankfurt: M. Suhrkamp, 1973), 69.

Ibid., 82.

Valéry, Eupalinos, 88.

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, Architecture as Signs and Systems for a Mannerist Time (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2004), 1.

Ibid., 9.

Ibid., 12.

Ibid., 73.

Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas: The forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1977), 87.

Jay Merrick, “The Death of Architecture,” in The Independent (4 April 2011). See →.

Lucy Lippard, Reconsidering the Object of Art: 1965-1975, (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1995).

Lucy Lippard and John Chandler, “The Dematerialization of Art,” in Art International Vol. XII, No. 2 (1968).