Life but how to live it—for years the name embellished the wall behind my bed: the place of love and desire, of fears and tears, of fatigue and regeneration. No question mark, thus no searching for sense, or meaning, or technologies. No comma, thus no singling out of some ontological given from the practices of sustaining, endangering, or losing it. Simply the pleasure and pain of engaging in social relations: of bitterly failing while jubilating, and cheering while messing it all up. It is the name of the Norwegian punk band that entered my life by chance when I turned up for a concert at the infamous Hamburg squat Rote Flora, and it was the first thing that came to mind when I heard about Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz’s new film project on punk archives and queer socialities.

[S]ocial relations made on grounds of jouissance “must be a queer sort of social bond, one that is the effect of the disruption of the given time of the social contract (heteronormativity), yet creates at a secondary level a new social ordering (queer sociality).”1

In the following pages I will attempt figure out how “the disruption of the given time of the social contract” happens and whether it can be viewed as an effect of politics.2 As the titles No Future and No Past (Boudry and Lorenz 2011, each 16mm, 15 min) suggest, the films concern themselves with time: Is it the time of heteronormativity, materialized in the rhythm of three-minute film reels and the intervening moments of blankness that disrupt the films’ flow? I will read the two works through the lens of Andrea Thal’s curatorial concept for her exhibition “Chewing the Scenery” and show that the disruption is an effect of chronopolitics, yet one that is simultaneously a visceral politics.3 Furthermore, echoing Elizabeth Povinelli, I will argue that the queer sociality of the films—not that displayed by the films but that evoked by their setting—while evolving from “lawless” jouissance, suggests a certain kind of ethics, namely, an ethics of remembrance.4 This ethics remains bound to violence—the violence of crime and normalcy—and thus confronts the punk archive with the challenge of facing heteronormativity, postcolonialism, and the impossibility of remembering that these produce.

Boredom and Indifference in Drag

The queer sociality staged in No Future and No Past—two films that are confusingly similar yet decidedly different—is characterized by boredom, indifference, and a simultaneous submission to and rejection of “the law.” The films culminate in a seemingly unmotivated act of destruction—Darby Crash smashes his guitar—that is less aggressive than it is detached. At the beginning, one sees what appears to be a band that has reformed after many years, not of their own volition but due to mysterious circumstances. The band appears to be preparing for an unnamed gig. Nothing would happen, one reckons, if it were not for on-screen director Werner Hirsch, who prompts the characters to say their lines and gives instructions that are followed—though unenthusiastically—by the four musicians grouped together in a punk-style rehearsal space. Expectations of punk negativity—implied by the infamous phrase “no future” and by the film’s cast, consisting of Ginger Brooks Takahashi (of the band MEN) as Darby Crash, Fruity Franky (of Lesbians on Ecstasy) as Poly Styrene, G. Rizo as Joey Ramone, and Olivia Anna Livki as Alice Bag—are finally met when Darby Crash has his solo performance. Or are they? The destruction of the guitar can also be read as an already canonized citation of rock culture. Similarly, the use of bodies and objects as instruments can be read as an established practice of experimental music. So, is it the gender drag that strikes the audience when Darby Crash—in reality a white guy from Los Angeles known for wearing typical punk-style outfits—appears on stage in a pink cashmere jacket, a miniskirt, patent leather high heels, and a pearl necklace?

Various codes of race, class, and gender are displayed on stage yet do not form a coherent picture; dominant English language is disrupted by Polish and French; heterosexual desire expresses itself in clichéd fantasies cut short by embarrassed laughter. Punk enters the scene through the wall design and through the repeated song “We’re Desperate” by X (“We’re desperate, get used to it / It’s kiss or kill”), which creates a framework around the non-relatedness of the protagonists. Since the performers are not “true” to their characters, instead engendering explicit misinterpretations that embody contemporary US queer feminism, one could interpret the event as a drag show—perhaps a show by famous late-1970s punk musicians performing queer feminism? What is missing, however, are explicit references to, for example, the queer cultural activism of LTTR (Ginger Brooks Takahashi) or to Nigerian post-independence politics (G.Rizo). One might defend the punk performers in drag against political amnesia, since what they perform in 1976 (the date given by No Past) is set in 2011. Or is it? Turn to No Future and you are suddenly transported to the year 2031. The question of memory then emerges with double strength: 1976 and 2011 now appear as indistinguishable past, while 2031 and 1976 simultaneously claim to be the present.

Felted time ensnarling the audience. I would say that yes, you can read No Future and No Past as drag. However, it is temporal drag: one film functions as a drag performance of the other. Since the acting in No Future is slightly more enthusiastic than in No Past, with emotions finding their way into facial expressions and gestures, one might read No Future as a reenactment of No Past. Or the other way round. Paradoxically, it is only in No Past that Joey Ramone says, “I am not excited by utopia. Utopia has not turned out good for me.” Though the more pressing question raised by Boudry and Lorenz’s chronopolitics would be: Is there “no past”? And is this a promise or a threat?

Queering the Violence of Remembrance

Remembering the violence of the past, or a past defined by violence, or the violence of a past that only enters life as memory (possibly as the memory of “no past”), is a challenging task. It might be difficult to even know if there is a past. There might be good reasons to live the past in the form of an apocalyptic future. Punk history, like many other his_herstories, provides strategies of remembrance that actively cope with and rework experiences of violence. Yet how do his_herstories connect? Feminist and migrant movements have drawn attention to the normalcy of everyday sexist and racist violence; queer politics has pointed out the violence of normalcy; and postfascist and postcolonial history try to understand intergenerational reenactments of historical violence. In these contexts, narratives of progress and transgression have been widely discredited. Thus, I cannot resist filling in the narrative gaps of No Future and No Past and asking what is happening behind the walls that are, as the films tell us, located in Berlin. I see the Turkish migrant community, by 1976 already second-generation, facing pressure to repatriate. I see a future present in 2031: a vital Herero community that defines the social and cultural life of the city yet lacks political power, since the German government still denies them full citizenship rights—thereby securing the heritage of the German Empire’s colonial politics and consolidating the exclusion of roughly one-sixth of Berlin’s population from the right to vote in 2011.

Since memory is organized according to established symbolic and socio-political orders (and sometimes disrupted by trauma), one way to challenge the dominant temporalities of (heteronormative) progress and transgression is through disidentification. Disidentification is a radically different gesture than the negation implied by “no future.” While Lee Edelman has argued that any politics subscribing to the notion of historical progress enforces a violent normalization, José Esteban Muñoz, in answering him, suggests the existence of a utopian thinking that itself resists grand narratives.5 This form of thinking claims radical queer imaginaries, which undermine the normativities of the heteronormative archive without installing teleologies or phantasmatic promises.6 Disidentification, according to Muñoz, is an aesthetic strategy that reimagines dominant signs or images through performance practices that restructure spectatorship, provoking in the audience “a mode of desiring that is uneasy.”7 Muñoz argues that the chronopolitics of disidentification are utopian: “the here and now is traversed and transgressed.”8 The repetition of colonial and heteronormative violence is disrupted, at least temporarily. The films of Boudry and Lorenz, as well as the considerations presented here, develop in a field of tension laid out by claiming the present of a negated future, which also contains the heritage of a newly assembled past. This field of tension is the space where queer desires and the reworking of heteronormative and post-colonial histories can unfold.

In a polemical gesture, Boudry and Lorenz begin No Future and No Past with a promise that is not at all promising, a promise that evolves from a mode of progressive time and teleological chronopolitics: “In those days, desires weren’t allowed to become reality, so fantasy was substituted for them. Films, books, pictures, they called it ‘art.’ But when your desires become reality, you don’t need fantasy any longer, or art.”9 If this swansong to fantasy and art were realized, it would thoroughly undermine Muñoz’s mode of uneasy desiring. Luckily, the films that are introduced by this motto instead unfurl elaborate fantasy scenarios. Desires have become reality, yet fantasy is by no means obsolete, since desires are fantasmatic in their reality and most real as fantasies. Nevertheless, as the spectator, one is troubled as to what happens when the same desires appear under two different rubrics—and therefore can neither function unequivocally as apocalyptic negativity nor as punk nostalgia.

Contagious Transtemporal Desires

Temporal Drag is the title of a catalogue that Boudry and Lorenz published this year.10 It introduces their works N.O. Body (2008), Contagious (2010), Salomania (2009), Charming for the Revolution (2009), and Normal Work (2007), which were part of their solo exhibition at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève (June 10–August 15, 2010). To understand these video and film installations as explorations of queer temporalities and forms of remembrance would be to locate their aim neither in extending the archive by collecting or creating objects, nor in archiving feelings and exhibiting the politics of emotions that go along with this. Rather, they create a network of cross-references that undermines linear time and generates an interplay of heterogeneous historical, social, cultural, and geopolitical sites, realized in biographical references that celebrate the singularity of individual lives that have been denied respect and recognition, or have even experienced abjection. It is never a singling out of an individual. Instead, we get to know “ek-static selves” (Judith Butler), relational beings, never themselves but always given over to the Other (the intimate, the proximate, the one from another time and place, or even the Other of the Other).11

The term “drag” in the title of the catalogue hints at a long history of travesti and sex or gender crossings, at performances and performative practices that restage gender norms and normative desires in campy, hyperbolic, and ironic ways. The catalogue also focuses on class and ethnic drag, which are, inherently, also moments of gender drag. Yet, according to Lorenz, who recently suggested the term “transtemporal drag,” the most interesting thing about drag is not that it repeats norms or repeats them wrongly, but that it introduces a distance to norms and processes of subjection.12 Transtemporal drag, crossings (temporal or otherwise), and the figure of contagion are tools that Boudry and Lorenz use for their chronopolitical explorations. They insert these tools into their work via sexual labor, simultaneously presenting and transforming the sexual labor of the protagonists and spectators. “Sexual labor” is a term invented by Boudry and Lorenz together with Brigitta Kuster. It highlights the fact that labor relations always also constitute specific historical forms of gendered and sexualized subjectivity. These labor relations require gendered and sexualized subjectivity in order to fulfill their capitalist function.13

Boudry and Lorenz’s explorations of temporalities comprise a multidimensional process that involves an active audience, performers who do not so much work, but become the material of a heterotopic production process. Early on in the process Boudry and Lorenz find a project partner they want to work with and then research archives (official or unofficial), following unseen paths, hidden traces, and obscure details that are usually considered awkward—ready to be infected and to carry the virus to places they want to link together so that a vibrant network emerges, a network that engages time, people, objects, and fantasies. Desire and the virus are intimately related, which hints at a certain queer heritage that Boudry and Lorenz are ready to take on.

Performers, Scenario, and Audience in a Rhizomatic Network

Desires traveling in images (Elspeth Probyn) become a driving force for the research process and for creating the rhizomatic network that involves—and inhabits—the performers, the scenario, and the audience. Images as modes of transport include individual fantasies as well as cultural imaginaries, celebrated, conventional, marginal(ized) or forgotten public imagery as well as metaphors that permeate language with visuality and the visual with words. An active audience uses images as entry points for connecting to its own personal archive. The audience is invited to (knowingly or unknowingly) inhabit a structural position in the processes of meaning production initiated by the artistic practice. Revealing this structural position is a decisive moment in Boudry and Lorenz’s films. It is not always as obvious as in Contagious, where the camera celebrates the entrance of the audience as if it were an Olympic team marching into a stadium. In N.O. Body, the audience is present in its absence; a lecturer addresses an empty nineteenth-century lecture hall, exploring her chosen research topic—herself. In No Future and No Past, however, the audience is decentered, forced to follow the course of events from a lateral position.

Feminist film theorist Teresa de Lauretis suggests that we understand the act of viewing as a shared fantasy in which relations of power and desire are played out.14 If we take her suggestion, then the question of the structural position of the audience, and the identifications and disidentifications this position enables, are just as important as the visible bodies, movements, figurations, and constellations that take place on stage. A fantasy scenario, as Lauretis explains—taking up the psychoanalysis of Jean Laplanche and Jean Pontalis—is characterized by the fact that each participant is simultaneously subject, object, and observer of the scene. Thus, the traditional division of labor between subject and object of desire is undermined. Furthermore, as spectator—in a reflexive position of “seeing oneself seeing” and “seeing oneself being seen”—one is seduced into becoming the “subject of feminism” (Lauretis) or, perhaps, the subject of politics, the politicized desiring subject, process and product of queering the audience.

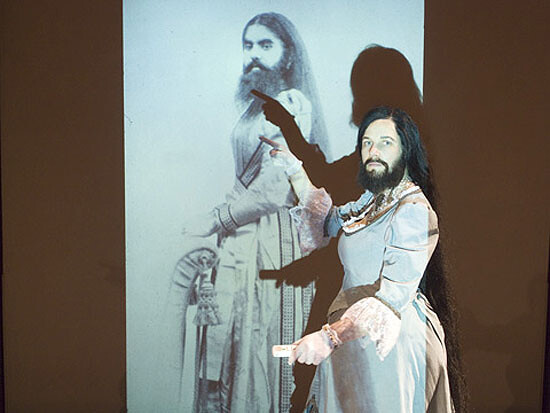

Considering the multidimensional process of “explorations into temporalities,” the question of time and timing in the production process plays a crucial role, from script to setting, cast to acting, sponsoring to spending, camera set-up to lighting, and finally cast to post-production. Boudry and Lorenz work with performers who are willing to be sucked into an intense and condensed production process that engages them not simply as performers but as researchers of the topic of at hand, employing bodily practice and visceral intellect. Bourdry and Lorenz develop almost all of their projects in close cooperation with Antonia Baehr, a.k.a, Werner Hirsch, who is usually the central performer. (Exception include Contagious, which features Arantxa Martinez and Vaginal Davis, and Salomania, with Ingrid Wu Tsang and Yvonne Rainer.) Hirsch usually embodies multiple figures simultaneously or in quick succession. In Charming for the Revolution he plays both of the film’s two characters, a dandy and a shabby unionist. Thanks to filmic montage, the two characters appear to inhabit the same space and observe each other skeptically. Each of the characters is himself a hybrid figure; the dandy turns into a cockatoo while the unionist becomes first a housewife and then a crow. Another example can be found in Normal Work, where Hirsch successively plays an aristocrat, a bourgeois lady, a housemaid, and a slave in blackface. The performance takes place in a Victorian setting that nonetheless includes various contemporary props, the most striking of which is a blown-up black and white photograph by Del LaGrace Volcano showing two trans men in erotic leather attire. Wallpapered behind the protagonist, the photograph provides him with sexual playmates as well as alter egos. At the same time, the photograph invites the spectator to enter the scene: one of the trans men looks directly into the camera, drawing my eye. I see myself being seen by the man in the photograph—I am an object of his desire—while simultaneously I see Hirsch performing historical figures enthralled by twenty-first century queer subculture. Seduced into the scene, I do not identify with the protagonists but instead actualize the sadomasochistic relationship between Victorian housemaid Hannah Cullwick and attorney Arthur Munby.15 In this way, as a spectator I perform the sexual labor of remembrance—not as an intellectual endeavour, but as a visceral entanglement. This entanglement is not beyond decision but is beyond the spectator’s control; he or she is held responsible for a past that may be “no past.”

In order to explain how the ethics of remembrance emerges from this visceral involvement of the audience—this jouissance—I would like to examine Andrea Thal’s curatorial approach in Chewing the Scenery. In traditional theatre language, “chewing the scenery” refers to overacting by on-stage performers. By contrast, the contributions to Thal’s exhibition at the off-site Swiss pavilion of the 2011 Venice Biennial shift attention to the audience and its visceral involvement in the scenery, facilitated by the activity of chewing. Chewing is an ambiguous activity, combining aggression and pleasure, destruction (of structures) and creation (of mash).16 Chewing is always already charged with expectations of incorporation or ejection, potential violence and/or desire. Thus, if we understand chewing as a form of perception and memorization—and a political practice—we must acknowledge its pleasurable and delightful dimensions as much as its reluctant, repellent, or nauseating ones. As a mode of approaching the scenery, chewing subverts the distinction between the individual and the social: while chewing places me within the scenery, it also places the scenery within me. But what is most interesting about No Future and No Past is that chewing reflects different temporalities that imply certain chronopolitical strategies.

The Chronopolitics of Chewing the Scenery

On the one hand, chewing the scenery is characterized by deferral: as long as one is chewing, it remains unclear whether this action will end in swallowing or spitting out; one could say that the temporality of chewing is defined by this “decision-to-come.” On the other hand, chewing the scenery also invokes the temporality of repetition and endurance, a temporality most pronounced in rumination. This second temporality shifts the focus to the fact that one is already digesting the scenery while chewing it, yet also points to regurgitation and its associated painful pleasures. In thinking about the political implications of both cases—the temporality of teleology and decision, or the temporality of repetition and loops—one might consider whether rumination is more appropriate to those who avoid facing their contribution to the violence of heteronormative, racist, and postcolonial histories, while swallowing or spitting out are more appropriate to those who have endured that violence. That said, if one wishes to acknowledge power differences and asymmetries in remembrance and historiography, it is crucial to avoid fixing them in predefined subject positions or constellations. Thus, if we understand chewing as taking place within shared scenarios, power and desire create and transform asymmetries and hierarchies rather than simply represent them.

The question then becomes: Who develops what kind of agency in designing the scenario? This brings us back to Werner Hirsch, who determines the course of events in No Future and No Past, and to the role of the audience as potential chewers of the scenery. Given the decisive role of the on-screen director in these films, what I as an audience member have to chew on is a tenacious rehearsal of the way in which the law instantiates itself. Hirsch orders Darby Crash to ask Poly Styrene about her future. He makes Poly Styrene give a political speech about her “desire to get out of here,” each line of which is prompted by the director. He makes everybody spit (!). Does this collective spitting imply a decision, a decision against swallowing? Swallowing what? Perhaps the “given time of the social contract (heteronormativity),” as Povinelli writes? Hirsch commands, “Darby Crash: Get married, have kids, settle down.—More authentic! Darby Crash and Poly Styrene kiss!—Stop!” While Hirsch, embodying the law, occupies a central position in the scene, one wonders why he directs from the back row, where he cannot get an overview of the situation. In addition, he conspicuously needs to read from the script, even losing track multiple times. Seen from the perspective of the audience, Hirsch, far from displaying authority, is just another participant in the group. Accordingly, when he orders the group to line up for a family portrait, he lines up right alongside them.

Keeping in mind the performative nature of the law, which only exists as long as and in the way it is reiterated, one could say that No Future and No Past are characterized by the temporality of repetition. This is supported by the fact that the films are presented in a loop. But here is where the confusion starts: the loop is and is not a loop. The films have the same setting, the same cast, and (nearly) the same script, but there are subtle differences between them. They thus embody the postructuralist notion that no repetition is ever exactly the same. The more often I watch the looped sequence of the two films, the less I am able to describe their similarities and differences and distinguishing between (no) future and (no) past becomes impossible. The time of progress and transgression breaks down. Does this happen independently from the fact that within the procedure of repetition each of the films is characterized by an internal rupture? The final scene of each film enacts the temporality of decision; rather than a deferral or a decision-to-come, there is a spitting out: Darby Crash plays a song and explores various aggressive and creative ways of engaging with his guitar. This is an intimate engagement driven by jouissance, beyond the distinction between pleasure and pain.

While this is a solitary, even antisocial, gesture, I would like to ask how it becomes social and whether it inspires the queer sociality promised earlier. Kathi Wiedlack provokes this question:

To imagine a possibility for political action and a politically active social group, community or subculture, as built on a disposition of jouissance, is not the same as to assert that jouissance can be shared. Nevertheless, regarding sexual acts, or equally ecstatic experiences like dancing in a mosh pit or shouting, screaming, and ranting in a crowd, these might actually come very close to such a shared experience of jouissance—a pleasurable as well as violent experience that tends to undo the singularity of the individual.17

The audience of No Future and No Past can experience such an undoing of the singularity of the individual through a camera technique that decenters the audience so that it can neither identify with the protagonists, nor exert any control over the scene. While No Future and No Past are concerned with time and a chronopoltics that viscerally engages the audience, what is even more challenging to the spectator, and what is more relevant for understanding the queer socialities implied by the films, is a certain spatial politics initiated by the camera movement: while the protagonists act in the direction of an imaginary frontal camera, the course of events is filmed from a lateral position.18 The axis between on-screen director Hirsch and the imaginary frontal camera, which exhibits his complicity with the authority of the gaze, cannot be shared by the audience. Yet, in watching from the side, the audience does not perceive Hirsch in a position more privileged than any other person in the scene. The instantiation of the law and its disruption unfolds as a process beyond the control of anyone inside or outside the scene. Furthermore, the camera is not only lateral, but also stationary. The audience must accept that some of the protagonists leave the picture occasionally, creating a further lack of visual control.

All the more important, then, that when Darby Crash’s solo performance starts, the lateral camera moves, claiming the view from the front, not in order to inhabit the position of authority but to offer itself to the performance of the protagonist. It follows the destructive-creative dance of the musician smashing his guitar. The camera zooms in, twists, turns, and lingers on details in an admiring, curious, or even loving way. Whereas the lateral camera displaces and decenters the spectator, the mobile camera destabilizes her_him. The camera’s whimsical movements do not exert control, but instead open up the scenario for the spectator to enter. While the protagonists look on indifferently as events unfolds, the spectator, sharing a disposition of jouissance, finds her_himself enjoying the pleasurable pain and painful pleasure of queer sociality beyond linear time. The two temporalities of chewing are not mutually exclusive after all. Rehashing may, at a certain point, find an end in spitting or shitting. As such, it is social, a way of designing the world through leftovers of one kind or another.

Maria Katharina Wiedlack, Punk Rock, Queerness, and the Death Drive (unpublished manuscript), 1–41. Internal quote from Elizabeth Povinelli, “The Part that has No Part: Enjoyment, Law and Loss,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 17(2–3) 2011, 288–308.

I would like to thank Kathi Wiedlack, who inspired me to write this article. In her in-progress dissertation Punk Rock, Queerness, and the Death Drive, she confronts Lee Edelman’s No Future with queer punk lyrics and subcultural practices. Offering a profound rereading of Edelman’s Lacanian-based antisocial thesis, she concludes that punk negativity can lead to a form of queer sociality without subscribing to fantasies of coherence, reproductive futurism or losing the pleasurable threat of jouissance from its desires.

“Chewing the Scenery” Venice Biennial 2011, Swiss Off-Site Pavillion, (June 1–October 2 2011, Teatro Fondamenta Nuove), curated by Andrea Thal, →.

See note 1.

Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004).

José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009)

Ibid., 75.

Ibid., 169.

This quote is borrowed from Derek Jarman’s film Jubilee (1977).

The term is coined by Elizabeth Freeman in her book Time Binds. Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2010). Pauline Boudry, Renate Lorenz (eds.), Temporal Drag (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz 2011).

Judith Butler, Undoing Gender (New York: Routledge, 2004).

Renate Lorenz, Queer Art. A Freak Theory (Bielefeld: transcript, forthcoming).

Pauline Boudry, Brigitta Kuster, Renate Lorenz (eds.), Reproduktionskonten fälschen! Heterosexualität, Arbeit und Zuhause (Berlin: b_books, 1999).

Teresa de Lauretis, The Practice of Love. Lesbian Sexuality and Perverse Desire, (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana UP, 1994).

Renate Lorenz (ed.), Normal Love. Precarious Sex, Precarious Love (Berlin: b_books, 2007).

For more detailed elaborations on the following, see Antke Engel, “Chewing the Scenery–Reading the Cud” in Chewing the Scenery, ed. Andrea Thal, (Zürich: edition Fink, 2011), 1–6 and 29–31.

Wiedlack, 19.

This set-up alludes to Andy Warhol’s film The Life of Juanita Castro (1965).