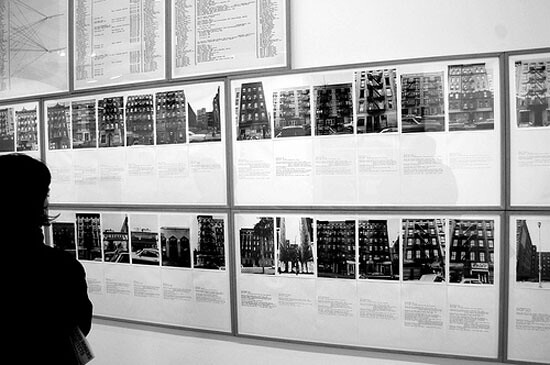

In 1971, a solo exhibition by German artist Hans Haacke, planned to take place at the Guggenheim in New York, was censored due to the artist’s intention to exhibit a work titled Shapolsky et al., Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971. One of the most discussed works of the 1970s, the piece brings together Haacke’s research on slumlord Harry Shapolsky’s real estate holdings in Manhattan. A series of over 140 photographs of run-down blocks of residential buildings displayed with detailed data from public records clearly exposed the NYC’s real-estate tycoon families’ monopoly over those slums. The Guggenheim decided to shut down the exhibition because it was deemed inappropriate. Rumors circulated that Guggenheim trustees might have been implicated in those dodgy financial dealings. The exhibition’s curator, Edward Fry, was then fired, and apparently never worked in the US again. Of course, Haacke’s work was not conspiratorial, as some had conjectured, but was a diligent archival excavation that has since become exemplary for the forms of institutional critique circulating at a time when self-organized artist initiatives abounded in New York.

Flash forward to 2011. Arab countries that have been enduring the legacy of colonialism and the backbreaking ideologies of the 1950s and 60s are revolting against decades of dictatorship. First the multitude of Tunis rises against Ben Ali, then Egypt overthrows Mubarak, and now Libya, Bahrain, Syria, and Yemen…. The results of these struggles are still uncertain as NATO and American forces (not to mention internal security forces and tribal leaders) react in the spirit of the times, catching on to the so-called intelligence oversights, and initiating campaigns of bloody intervention. However, what was noted as singular, inspiring, and unprecedented about these revolts was the degree of spontaneous and organic self-organization. Without a leader, commander, or traditional political party hierarchies, hundreds of thousands of bodies descended into capital cities and town centers and invented new economies of exchange, assistance, and expertise—be they medical, visual, or linked to basic sustenance on the streets.1 Even more recently, images from protests in Spain, albeit stemming from a very different set of crucial demands vis-à-vis the state, have been notable in the way they similarly portray self-organized, networked, collaborative, and mobile forms of action—also equally leaderless and still ongoing.

In the meantime, related battles are being fought on the terrain of art and culture. Billions of petro- and real estate dollars have made it possible to invest in bringing mega art institutions, such as the Louvre, the Guggenheim, and Christie’s to Abu Dhabi and its environs. As has been clear to many, the massive interest and investment in the art of the region (whether the Arab region or the Middle East in particular) is turning it into an asset class of its own, a new commodity, in surprising and sometimes less-surprising ways. Yet this burgeoning interest (both locally and internationally) in the category of Arab art sometimes goes beyond mere market trends, and evinces not only a familiar form of political control, but has always been, for many critics and commentators, the other arm of foreign policy, exerting its power through cultural politics.2

Informed by modernist, universalist discourse following World War II, as well as the rise of capitalist and globalization discourses in more recent decades, the ideological forces driving the field of art have become many-sided and increasingly indistinguishable from one another. Roughly, on the one hand there is the art market composed of collectors, buyers, dealers, investors, and auction houses; on the other, there are the local and international donor agencies, private funders, promoters, audiences, and artist projects. Add to this a third body of centralized cultural policy-making and state-sponsored art, and it becomes clear that these various interests cannot be easily separated. Although foreign and domestic cultural policy in the arts is not a new political phenomenon (for it includes the World Fairs of the nineteenth century, the support of Abstract Expressionists in the modern period, through to the biennials, triennials, and the dubbing of a transnational category of art today3), let us be clear about an age-old and inevitable relationship between art (its production, exhibition, not to mention its existence) and money. Yet could and should the idea and the category of art be understood solely under these terms?

Some have speculated that many of these contradictions and ill-fated relationships came to a head when, more recently, an international group of highly visible artists reacted to a recent Human Rights Watch report regarding the decrepit and unjust state of migrant workers in the UAE by writing and circulating a letter titled “Who’s Building the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi?” The group of artists (many of whom are already part of the Guggenheim’s collection in New York and have exhibited there) state in their letter that they will boycott the Guggenheim branch in Abu Dhabi if it does not provide the exploited workers building the gigantic Frank Gehry–designed structures with adequate rights and privileges.4 However, although this gesture is ethically necessary, one wonders whether it actually sets in motion a critique of the structure of art institution-building practices fundamentally. As such, while the boycott targets the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi (where many of these very artists’ works would have been exhibited, and possibly owned), why not also begin questioning the other institutions that carry and exhibit their work? Who built, renovated, or funded, say, Mathaf in Doha, the private galleries of Dubai, let alone museums and galleries throughout the Western world?

In the neighboring emirate of Sharjah, politics (and even budgets) in the arts have not been identical to the importation of cultural institutions to Saadiyat Island—the massively costly collection of islands especially built for these mega institutions in Abu Dhabi. The Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF)—in part the brainchild of Jack Persekian, who helped found it in 2009 as Artistic Director of the Sharjah Biennial—was perceived by some as a more organic “umbrella” platform for contemporary artistic production and reflection, producing the well-attended Sharjah Biennial and the yearly March Meeting, as well as artist residencies, publications, and numerous other initiatives and programs.

Funded by the ruling Sheikh Sultan Al-Qassimi and funded through Sharjah’s Ministry of Culture, the foundation’s remit was in part to showcase modern and contemporary art and provoke discussion about its relationship to its immediate context and ecosystem (at least through its biennial, which in its early iterations exhibited painting, drawing, and sculpture, and at a later stage came to include sonic and visual arts production, workshops, outreach events, and even social or political critique by extension through some of the projects it hosted). Whether it succeeded or not is a point of contention. For some, it pushed certain important limits, broadening the scope of Sharjah as an urban locale, and over the years producing reverberations that were seen as essential for keeping networks and conversations open. Yet, “in the eyes of cynics,” as Hanan Toukan writes in her recent article on the matter, the foundation and the Biennial remain “an autocratic regime’s futile attempt to market a humane and civilized face to the rest of the world.” Possibly all funding and support in the so-called Arab and Gulf regions is merely the legacy of post-Cold War diplomacy and “the culmination of the politically motivated space that has been developing in between the new markets on the one hand and the civil society formula as the conduit for international cultural diplomacy and soft power on the other.”5

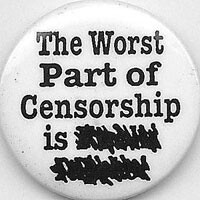

A month after the opening of the tenth edition of Sharjah Biennial on March 16, 2011—curated by Suzanne Cotter, Rasha Salti, and associate curator Haig Aivazian—Jack Persekian was fired. The official explanation for the sacking cited an allegedly offensive artwork by Mustapha Benfodil for having sparked a chorus of disapproval from certain members of the public, stating that, given his role as director, Persekian should have shown more responsibility toward local sensitivities, tastes, and the emirate’s stringent laws against insulting Islam. In addition, the work was censored and removed from view, and it was also said that other works were tampered with or placed “under review.” In a contestable piece, curator Okwui Enwezor recently wrote:

What undid Persekian, I would argue, was actually a confluence of forces: the irreconcilability of the ambitions he held for the Sharjah Art Foundation as it grew, his supporters’ false impression that Sharjah was no different from any other cosmopolitan city, and the narrow space he had to navigate between transgression and conformity that his patrons had allowed him. In the end, he could not serve these conflicting constituencies.6

In order to protest against these moves and express solidarity with Persekian, a group of individuals collectively wrote a protest letter and posted an online petition, which was signed by around 1600 art practitioners, those with or without a stake (including artists, writers, curators, biennial and museum directors, and so forth).7 This was accompanied by statements from curators Rasha Salti and Haig Aivazian decrying the sad turn of affairs, but more importantly highlighting that they are not “outsiders” imposing their views on a local public, and are well aware of the thin line between sensitivity to local laws and outright (self-)censorship, not to mention that Aivazian himself was a longtime inhabitant of Sharjah throughout the 1990s.

Although censorship and self-censorship were, are and always will remain an issue in the showcasing of art, whether in the UAE or elsewhere (or perhaps one should say that overt censorship exposes a show of force by the powers-that-be when the implicit rules of self-censorship fail), it is clearly not the only issue at stake now, several weeks after these events began to unfold.8 In some (probably expected) odd-but-happy marriage between SAF, now run by Sheikha Hoor Al-Qasimi, and Fitz and Co (ironically, the New York–based company hired to promote Sharjah Biennial 10), a PR campaign was launched to condemn the petition, reinstate and reiterate the reasons for the ruler’s decision to oust Persekian, and generally save face. This included articles in the press, circulating disclaimers forcibly signed by Persekian, and a moderate, conciliatory letter sent in the name of Hoor Al Qasimi to all artists participating in the Biennial. As such, a call to boycott is not a benign gesture at all, as a way of saying “I prefer not to” that can always be a vibrant form of protest and abstention. Meanwhile, via the Facebook conversations and comments, published articles, and live polemic this story generated, some of the retorts circulating in reaction to the letter of protest ran along the lines of “What did you expect from the UAE except censorship?”, “Censorship and self-censorship are endemic to the art world, what’s the point of protesting against them?”, “What is the real reason behind this cultural colonization of the UAE? You should get out of there,” “These Gulf art world protests can be seen as a delayed symptom of the fact that artists were in no way at the forefront of the Arab spring,” “This is what you get when you go into contract with this industrial-type complex for contemporary art,” and so on.

Some of these claims are indeed accurate and legitimate, while others are problematic, deeply reductionist, and borderline racist. For one, they implicitly view the Gulf as a singular out-group entity to be discriminated against for its backwardness and lack of local culture, without nuance or differentiation. They create false dichotomies between original and imported, authentic and fake, or local and transnational, however contentious or loaded the politics of these terms may be. In addition, viewing any or all engagement with artistic practices in this region as solely informed by liberal, unrestrained market forces and a form of colonization, disregards some of the vital and powerful artwork at stake, including work that calls into question this very market-engineered dynamic (Hans Haacke’s work being but one example), and in some instances missed the point. The history of institutional critique is an old and fruitful one, and the relationship between ideological function and commodification of art has been extensively written about. It is time to revisit these in a serious fashion, in practice—and not dismiss all artworks in a facile manner by confusing the whole of the machine with the potentialities of its parts, which, in innumerable cases, in no way reify it.

Moreover, some of these reactions neglect the fact that large-scale institutions are institutions nonetheless, in that their funding comes, if not from the state, then from private banks, trustees, or those with capital interest. From this strictly structural viewpoint, whether we are in Sharjah or in London, the forces of the art market in its many guises, as well as the dominant cultural policy, are and have always been the major, heavyweight protagonists. In other words, this is the life and mechanics of the art market (and of capitalism itself), which is as old as (if not constitutive of) the so-called art world itself. If some insist that we should look at this matrix from a purely socio-political and economic perspective, perhaps it would be more productive to focus, in the words of anthropologist Kirsten Scheid, on what we do not know about “contemporary Arab art”—from its audiences to its forms, concepts, historiography, all the way to its funding and institutions.9

Furthermore, the problematic idea that one should not protest censorship or engage with (state-sponsored) art institutions in this area of the world (since these emirates are a bunch of dictatorships) is equal to saying one should not work with national cultural centers or with art institutions in China, Syria, Jordan, or anywhere else where autocratic rule is rampant or brutal (not to mention so-called liberal democracies where censorship can be just as pervasive; the US and Lebanon are just two random examples). The idea that established museums, galleries, funders, cultural/foreign policies, and even art history anthologies make visible and invisible what is politically convenient at a given time is high school textbook material.

Instead of merely presenting materialist conceptions of art and power, reiterating how capital operates in “liberal democracies” and dictatorships alike with what Slavoj Žižek has called “a moralizing critique of capitalism,” let there be a renewed, vibrating critique of institutions or, in the words of artist Doug Ashford, “deprofessionalization.”10 As Ursula Biemann and Shuruq Harb have written,

Initiatives for building strong civil networks and institutions are bound to emerge now … that will lay the grounds for a discourse on art and visual culture from the bottom up. We need platforms where artists can speak their mind about foreign investment in the arts, national cultural politics, massive institution building, their relation to the international art industry, and their needs for de-centered and revised histories.11

This is exactly the time to learn from the Arab revolts, from their visceral, urgent, organic self-organization, and their rejection of hegemonic structures. It is the time to re-celebrate and initiate independent, provisional, improvisational, idiosyncratic, contingent organizations, collectives, initiatives, artworks, fanzines, and a time to revisit old and new conversations and excavate art practices that—whether within the walls of the museum or outside it—have dedicated themselves, sometimes radically and without naïveté, to interrogating the weight of institutional idioms and capital in producing, circulating, and consuming art. Could now be the prescient time to re-imagine an alternative?

As a side note, Lebanon is seen by many as an exception to these mass demonstrations to bring down the old guard, as it struggles to form a government, stuck as it is between the status quo of the March 8 and March 14 coalitions/politicians. And when obedient partisans do take to the streets, it’s more often than not in support of one of the two distinct alliances ruling the country in different guises for almost as long as the country existed, and thus, in the words of historian Faisal Devji, cancel each other out. Further south-east near the Persian-Arab Gulf, recent Gulf and international media have released news bulletins regarding the tracking down and detention of bloggers, activists, and even academics demanding free elections and the creation of political parties in these autocratic emirates.

Irrespective of the type and interest of the work shown here, note how Ministries of Foreign Affairs mandate their cultural centers in Arab cities, often perpetuating their colonial legacy as the new cultural outpost. Paris and London being two such epicenters, with the French Cultural Centers and British Councils.

For instance, consider the 1970 Biennial of Alexandria, the 1974 First Arabic Biennial of Baghdad, and the 1975 Biennial of Arab Countries of Kuwait, to name a few examples of state-sponsored interests and promotion of art in the so-called Arab region.

See →.

Hanan Touqan, “Boat Rocking in the Art Islands: Politics, Plots and Dismissals in Sharjah’s Tenth Biennial,” Jadaliyya, May 2, 2011, see →.

Okwi Enwezor, “Spring Rain: Okwi Enwezor on Ai Weiwei and the Sharjah Biennial,” Artforum (Summer 2011), see →.

See →.

For example, note the strange, but not unpredictable wall text (or, rather, the blatant disclaimer) used in an Emily Jacir exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2009 stating that “SFMOMA is committed to exhibiting and acquiring works by local, national, and international artists that represent a diversity of viewpoints and positions. Works of art can engender valuable discussion about a range of topics including those that are difficult and contested, such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Additional information about Emily Jacir’s Where We Come From, including a list of frequently asked questions, is available at the information desk.” See Tyler Green, “SFMOMA installed unusual wall-text in Emily Jacir gallery,” →, and →.

Kirsten Scheid, “What we do not know: Questions for a study of contemporary Arab art”, ISIM Review 22 (Autumn, 2008).

Slavoj Žižek, Living in the End of Times (London: Verso, 2011), 473. Doug Ashford and Naeem Mohaiemen, “Naeem Mohaiemen and Doug Ashford Dialogue,” in Naeem Mohaiemen, Collectives in Atomised Time (Calaf: IDENSITAT Associació D’Art Contemporani, 2008) 50.

Ursula Biemann and Shuruq Harb, “Ibraaz Platform 001,” June 2011, see →.