→ Continued from “Culture Class: Art, Creativity, Urbanism, Part I” in issue 21.

PART TWO: CREATIVITY AND ITS DISCONTENTS

Culture is the commodity that sells all the others.

—Situationist slogan

Soon after the collapse of the millennial New Economy that was supposed to raise all boats, Richard Florida, in his best-selling book The Rise of the Creative Class (2002), instituted a way of talking about the “creative class”—the same class put center stage by Sharon Zukin, David Brooks, and Paul Fussell—in a way that framed it as a target group and a living blueprint for urban planners.

Florida may see this class, and its needs and choices, as the savior of cities, but he harbors no apparent interest in its potential for human liberation. When Robert Bruininks, the president of the University of Minnesota, asked him in an onstage interview, “What do you see as the political role of the creative class—will they help lead society in a better, fairer direction?” Florida was, according to faculty member Ann Markusen, completely at a loss for a reply.1 Some who frame the notion of a powerful class of creative people—a class dubbed the “cultural creatives” by Paul H. Ray and Sherry Ruth Anderson in their book of that name published in 2000—see this group as progressive, socially engaged, and spiritual, if generally without religious affiliation, and thus as active in movements for political and social change. In general, however, most observers of “creatives” concentrate on taste classes and lifestyle matters, and are evasive with respect to the creatives’ relation to social organization and control.

Richard Lloyd, in Neo-Bohemia: Art and Commerce in the Postindustrial City, in contrast to Ray and Anderson, finds not only that artists and hipsters2 are complicit with capital in the realm of consumption but, further, that in their role as casual labor (“useful labor,” in Lloyd’s terms), whether as service workers or as freelance designers, they also serve capital quite well.3 The Situationists, of course, were insistent on tying cultural regimes to urban change and the organization and regulation of labor. Sharon Zukin, in her ground-breaking book Loft Living, provided a sociological analysis of the role of artists in urban settings, their customary habitat.4 But urban affairs, sociological and cultural analysis, and the frameworks of judgment have changed and expanded since Zukin’s work of 1982. In his book The Expediency of Culture (2001), George Yúdice leads us to consider the broad issue of the “culturalization” of politics and the uses and counter-uses of culture.5 Concentrating especially on the United States and Latin America, Yúdice’s concern is with explicating how culture has been transformed into a resource, available both to governmental entities and to population groups. He cites Fredric Jameson’s work on “the cultural turn” from the early 1990s, which claims that the cultural has exploded “throughout the social realm, to the point at which everything in our social life—from economic value and state power to social and political practices and the very structure of the psyche itself—can be said to have become ‘cultural.’”6 Yúdice invokes Michel Foucault’s concept of governmentality, namely, the management of populations, or “the conduct of conduct,” as the matrix for the shift of services under neoliberalism from state to cultural sectors. Foucault’s theories of internalization of authority (as well as those of Lefebvre and Freud) are surely useful in discussing the apparent passivity of knowledge workers and the educated classes in general. Yúdice privileges theories of performativity, particularly those of Judith Butler and Eve Kosovsky Sedgwick, over the Situationists’ “society of the spectacle,” describing how identities, including identities of “difference,” are performed on the stage set by various mediating institutions.7 Indeed, he positions the postwar marketing model—“the engineering of consent,” in Edward Bernays’s potent, widely quoted phrase—at the heart of contemporary politics and invokes the aestheticization of politics (shades of Walter Benjamin!) that has been fully apparent in the US since the Reagan administration.8 As I have suggested, this channels much political contestation in advanced societies to consumer realms, from buying appropriate items from firms that advance political activism and send money to NGOs,9 to the corporate tactic of appealing to identity-based markets, such as gay, female, or Latino publics; but also to the corporate need to foster such identities in hiring practices in the name of social responsibility.

In considering the role of culture in contemporary societies, it may be helpful to look at the lineage and derivation of the creative-class concept, beginning with observations about the growing economic and social importance of information production and manipulation. The importance of the group of workers variously known as knowledge workers, symbolic analysts, or, latterly, creatives, was recognized by the late 1950s or early 1960s. Peter Drucker, the much-lionized management “guru,” is credited with coining the term “knowledge worker” in 1959, while the later term “symbolic analysts” comes from economist Robert Reich.10

Clark Kerr, a former labor economist, became president of the University of California, in the mid-1960s. This state university system, which has a masterplan for aggressive growth stretching to the turn of the twenty-first century and beyond, was the flagship of US public universities and established the benchmarks for public educational institutions in the US and elsewhere; it was indended as the incubator of the rank-and file middle class and the elites of a modern superpower among nations in a politically divided world. Kerr’s transformative educational vision was based on the production of knowledge workers. Kerr – the man against whom was directed much of the energy of Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement, derisively invoked by David Brooks – coined the term the “multiversity” in a series of lectures he gave at Harvard in 1963.11 It was Kerr’s belief that the university was a “prime instrument of national purpose.” In his influential book The Uses of the University, Kerr wrote,

What the railroads did for the second half of the last century and the automobile for the first half of this century may be done for the second half of this century by the knowledge industry.12

Sociologist Daniel Bell, in his books The Coming of Post-Industrial Society (1973), and Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (1976), set the terms of the discourse on the organization of productive labor (although the visionary educational reformer Ivan Illich apparently used the term “post-industrial” earlier); Richard Florida claims Bell as a powerful influence.13 The term post-Fordism, which primarily describes changes in command and control in the organization of the production process, is a preferred term of art for the present organization of labor in advanced economies, retaining the sense of continuity with earlier phases of capitalist organization rather than suggesting a radical break resulting from the rise of information economies and changes in the mode of conducting and managing the labor process.14

Theories of post-Fordism fall into different schools, which I cannot explore here, but they generally include an emphasis on the rise of knowledge industries, on the one hand, and service industries on the other; on consumption and consumers as well as on productive workers; on the fragmentation of mass production and the mass market into production aimed at more specialized consumer groups, especially those with higher-level demands; and on a decline in the role of the state and the rise of global corporations and markets. Work performed under post-Fordist conditions in the so-called knowledge industries and creative fields has been characterized as “immaterial labor,” a (somewhat contested) term put forward by Italian autonomist philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato. Within or overlapping with the broad category of immaterial labor are types of labor deemed “affective labor” (Hardt and Negri); these include not only advertising and public relations—and, many artists would argue, art—but all levels of labor in which the worker faces the public, which include many service industries, and eventually permeates society at large.15 In “Strategies of the Political Entrepreneur,” Lazzarato writes:

If the factory can no longer be seen, this is not because it has disappeared but because it has been socialized, and in this sense it has become immaterial: an immateriality that nevertheless continues to produce social relations, values, and profits.16

These categories look very different from Florida’s.

Andrew Ross writes that the creative-class concept derives from Prime Minister Paul Keating’s Australia in early 1990s, under the rubric “cultural industries.”17 Tony Blair’s New Labour government used the term “creative industries” in 1997 in the rebranding of the UK as Cool Britannia. The Department of National Heritage was renamed the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) and promoted technological optimism, a youth cult, and, in Ross’s words, “self-directed innovation in the arts and knowledge sectors.” Both Ross and the social psychologist Alan Blum refer to the centrality of the idea of constant reinvention—of the firm and of the person—as a hallmark of the ideal conditions of the creative class. Ross points to the allure of the “creative industries” idea for a wide array of nations, large and small, of which he names Canada, the US, and Russia and China—we should add the Netherlands to this list—long before Florida’s particular configuration shifted emphasis away from the industries and to the very person of their denizens, and to biopolitics.

In describing the “creative class,” Florida credits Paul Fussell and gives David Brooks a brief nod.18 Despite building on writers like David Harvey and perhaps other, unnamed theorists on the left, Florida offers the prospect of a category of “human resources” who will, all unbidden, and at virtually no cost to anyone but themselves, remake your city quite to your liking. Rather than portraying the right to the city, as Harvey had termed it, as the outcome of struggle, Florida’s path to action is predicated on the inevitability of social change, in which the working class and the poor have already lost. I will say more about that a bit later, but first, I’ll consider the creative class itself.

What Florida has called the rise of the creative class Sharon Zukin called, in Loft Living, the artistic mode of production.19 Zukin, who never quite explains her phrase, describes the production of value and of space itself, interpretable in Lefebvre’s terms. Whereas Zukin traced the entire process from its inception to its present outcome, teasing out the structural elements necessary to bring about urban change and demonstrating how such change affects residents and interested classes, in Florida’s account the process disappears in a welter of statistical number-crunching and empirical markers by which to index the success of the creative class. Crucial to Zukin’s analysis is the eventual displacement of artists, a development not addressed by Florida, whose creative class encompasses high earners in industries extending far beyond artists, the vast number of whom do not command big incomes.

Zukin had already shown that integral to the artistic mode of production is the gradual expansion of the “artistic class,” suggesting how the definition of “artist” expanded and how the epistemology of art changed to fit the sensibilities of the rising middle class. Zukin—writing in 1982—asserts:

The new view of art as “a way of doing” rather than a distinctive “way of seeing” also affects the way art is taught. On the one hand, the “tremendous production emphasis” that [modernist critic] Harold Rosenberg decries gave rise to a generation of practitioners rather than visionaries, of imitators instead of innovators. As professional artists became facile in pulling out visual techniques from their aesthetic and social context, they glibly defended themselves with talk of concepts and methodology. On the other hand, the teaching of art as “doing” made art seem less elitist.… Anyone, anywhere can legitimately expect to be an artist … making art both more “professionalized” and more “democratized.”… This opened art as a career.20

Zukin offers a sour observation made in 1979 by Ronald Berman, former chairman of the US National Endowment for the Humanities:

Art is anything with creative intentions, where the word “creative” has … been removed from the realm of achievement and applied to another realm entirely. What it means now is an attitude toward the self; and it belongs not to aesthetics but to pop psychology.21

I cannot address the changes in the understanding of art here, or the way its models of teaching changed through the postwar period—a subject of perpetual scrutiny and contestation both within the academy and outside it. A central point, however, is that the numbers of people calling themselves artists has vastly increased since the 1960s as the parameters of this identity have changed.

Florida enters at a pivot point in this process, where what is essential for cities is no longer art, or the people who make it, but the appearance of its being made somewhere nearby. As a policy academic, Florida repeatedly pays lip service to the economic, not lifestyle, grounding of class groupings, as he must, since his definition of “creative class” is based on modes of economically productive activity. Economic data, however, turn out not to be particularly integral to his analyses, while the use to which he puts this category depends heavily on lifestyle and consumer choices, and Florida includes in the creative class the subcategory of gay people as well as categories of “difference,” which are both racial/ethnic and include other identity-related groupings independent of employment or economic activity. This does not contradict the fact that we are talking about class and income. Although the tolerance of “difference” that figures in Florida’s scenario must certainly include of people of color working in low-level service categories who appear in significant concentrations in urban locales (even if they go home to some other locale), the creative class are not low-wage, low-level service-sector employees, and artists, certainly, are still disproportionately white.

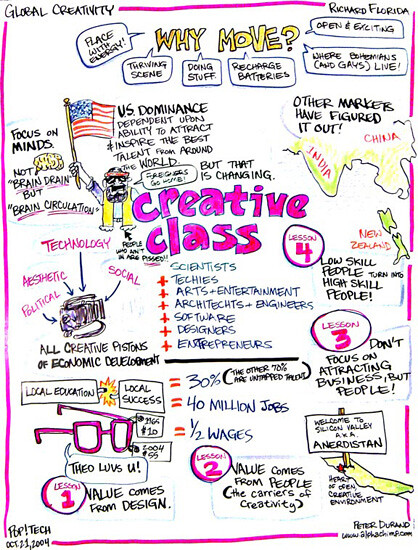

Florida’s schema is influenced by basic American economic and sociological texts—including Erik Olin Wright’s powerful description of the new professional-managerial class (sometimes called the new petite bourgeoisie to differentiate it from the “old petite bourgeoisie,” a class of small shopkeepers and the like whose declining fortunes and traditionalist world view have left them disaffected or enraged).22 But Florida’s categories are more directly derived from the US government’s Standard Occupational Classification, or SOC, codes. His creative-class grouping includes “a broad group of creative professionals in business and finance, law, health care and related fields,” who “engage in complex problem solving that involves a great deal of independent judgment and requires high levels of education or human capital.”23 Within it is a “super-creative core [of] people in science and engineering, architecture and design, education, arts, music, and entertainment … [whose] job is to create new ideas, new technology and/or new creative content.”

Doug Henwood, in a critique from the left, notes that Florida’s creative class constitutes about 30 percent of the workforce, and the “super creative core” about 12 percent. Examining one category of super-creatives, “those in all computer and mathematical occupations,” Henwood remarks that some of these jobs “can only be tendentiously classed as super creative.”24 SOC categories put both call-center tech-support workers and computer programmers in the IT category, but call-center workers would surely not experience their jobs as creative but “more likely as monotonous and even deskilled.” What is striking in Florida’s picture is, first, not just the insistence on winners and losers, on the creatives and the uncreatives—recalling the social divisions within Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel Brave New World—but on the implicit conviction that job categories finally do provide the only source of real agency regardless of their content. Second, the value of the noncreatives is that they are nature to the creatives’ culture, female to their male, operating as backdrop and raw material, and finally as necessary support, as service workers. Stressing the utility of random conversations in the street, à la Jane Jacobs, Florida treats the little people of the streets as a potent source of ideas, a touchingly modern[ist] point of view.

In an online consideration of Florida’s thesis, Harvard Economist Edward Glaeser, a right-leaning mainstream critic, expresses admiration for Florida’s book as an engagingly written popularization of the generally accepted urbanist maxim that human capital drives growth, but he fails to find any value added from looking at creative capital as a separate category. Glaeser writes:

[T]he presence of skills in the metropolitan area may increase new idea production and the growth rate of city-specific productivity levels, but if Florida wants to argue that there is an [effect] of bohemian, creative types, over and above the effect of human capital, then presumably that should show up in the data.25

Glaeser ran statistical regressions on the population-growth data on four measures: (1) the share of local workers in the “super creative core”; (2) patents per capita in 1990; (3) the Gay Index, or the number of coupled gay people in the area relative to the total population; and (4) the Bohemian Index—the number of artistic types relative to the overall population.

Glaeser concludes that in all the regressions the primary effects on city growth result from education level rather than any of Florida’s measures and that in fact in all but two cities, “the gay population has a negative impact.” He concludes:

I would certainly not interpret this as suggesting that gays are bad for growth, but I would be awfully suspicious of suggesting to mayors that the right way to fuel economic development is to attract a larger gay population. There are many good reasons to be tolerant, without spinning an unfounded story about how Bohemianism helps urban development.26

Further:

There is no evidence to suggest that there is anything to this diversity or Bohemianism, once you control for human capital. As such, mayors are better served by focusing on the basic commodities desired by those with skills, than by thinking that there is a quick fix involved in creating a funky, hip, Bohemian downtown.27

Max Nathan, an English urbanist at the Centre for Cities, an independent research institute in London, observes that “there’s not much evidence for a single creative class in the US or the UK. And although knowledge, creativity, and human capital are becoming more important in today’s economy, more than 20 years of endogenous growth theory already tells us this.” He concludes, “Creativity and cool are the icing, not the cake.” 28

American sociologist Ann Markusen, left-leaning but agreeing with Glaeser, further cautions that “human creativity cannot be conflated with years of schooling.”29 Some of the occupations included in Florida’s sample do not call upon creative thinking, while many manual tasks do just that; furthermore, it hardly needs to be noted that human qualities and attributes are not themselves merely produced by schooling.

Florida’s use of the US government’s SOC categories, lumping together artists and bohemians with all kinds of IT workers and others not remotely interested in art or bohemia, has been identified by many other observers—perhaps especially those involved in the art world—as a glaring fault. Florida fails to note the divergent interests of employees and managers, or younger and older workers, in choices about where to live: it seems, for example, that the young move into the city while somewhat older workers move out to the suburbs, where managers tend to cluster. But Florida’s book found its ready audience not among political economists but in some subset of municipal policy makers and rainmakers for government grants, and in business groups.

As Alan Blum suggests, Florida’s work is directed at “second tier” cities pursuing “an ‘identity’ (as if merchandise) that is to be fashioned from the materials of the present.”30 Second tier cities tend to glorify the accumulation of amenities as a means of salvation from an undistinguished history, a chance to develop and establish flexibility. Blum’s critique emphasizes the platitudinous banality of Florida’s city vision, its undialectical quality and its erasure of difference in favor of tranquility and predictability as it instantiates as policy the infantile dream of perpetually creating oneself anew. In my estimation, Scandinavian societies seem to have faced the postwar world by effacing history and re-presenting themselves as factories of design; visiting Copenhagen’s design museum, I was amazed that a large wall inscription in the exhibition of the great designer Arne Jacobsen emphasized both his complete lack of “interest in Utopia” and his fondness for white tennis flannels. One can think of many cities, regions, and nations that would prefer to transcend an earlier mode of economic organization, whether agricultural or Fordist, in favor of a bright new picture of postindustrial viability. The collective failure of imagination can be extended to entire peoples, through the selective re-creation, or frank erasure, of historical memory. The entire cast of the creative-class thesis is centered on the implicit management of populations, through internalized controls: in essence, Foucault’s governmentality.

Florida was teaching at Carnegie Mellon in the Rust Belt city of Pittsburgh when he formulated his thesis, but subsequently moved to the University of Toronto, where he now heads the Martin Prosperity Institute at the Rotman School of Management, and is Professor of Business and Creativity. His website tags him as “author and thought-leader.” Florida has developed a robust career as a pundit and as a management consultant to entities more inclusive than individual firms or industries. Management consulting is a highly lucrative field that centers on the identification of structures of work organization and methods of organizing workers in a manner persuasive to management. Management theory, however, even in the industrializing 1920s, has often claimed that creativity and interpersonal relations would transform management, leading to an end to top-down hierarchies and a harmonizing of interests of workers and management.

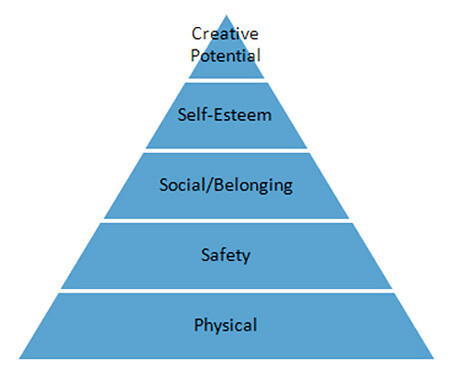

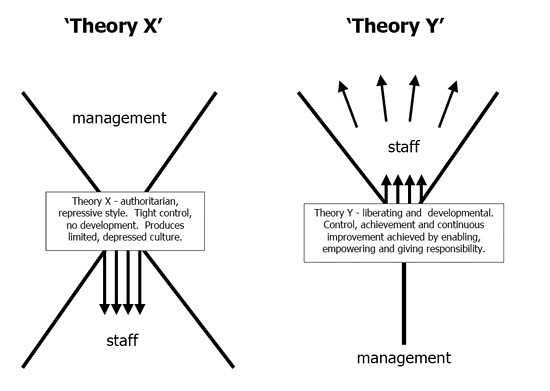

Speaking personally, in the early 1970s I worked in a small, Peter Drucker–advised publishing company in Southern California to which Drucker, the management idol then riding the crest of his fame, made regular visits. We were schooled to regard the management tool called Group Y, widely used by Japanese companies, as the new gospel of employee-management relations. As a concept, Group Y is traceable to Douglas McGregor, a professor at MIT’s school of management. Influenced by the social psychologist Abraham Maslow’s then widely popular theories of human self-actualization, McGregor promoted the idea of employees and workers as human resources. In The Human Side of Enterprise (1960), McGregor developed his highly influential paradigm of employee management and motivation in which management is characterized by one of two opposed models, Theory X and Theory Y.31 In Theory X, people are seen as work-averse and risk-averse, uninterested in organizational goals, and requiring strong leadership and monetary incentives. Theory Y, in contrast, sees work as enjoyable and people as naturally creative and self-directed if committed to work objectives. (McGregor, unrealistically, hoped his book would be used as a self-diagnostic tool for managers rather than as a rigid prescription.) Building on McGregor’s theory, and long after I left my bliss-seeking editorial shop, William G. Ouchi invoked Theory Z to call attention to Japanese management style.32

Starting in the early 1960s, Japanese management made extensive use of “quality circles,” which were inspired by the postwar lectures of American statisticians W. Edwards Deming and J. M. Juran, who recommended inverting the US proportion of responsibility for quality control given to line managers and engineers, which stood at 85 percent for managers and 15 percent for workers.33 As the Business Encyclopedia explains, Japanese quality circles meet weekly, often on the workers’ own time and often led by foremen. “Quality circles provide a means for workers to participate in company affairs and for management to benefit from worker suggestions. … [E]mployee suggestions reportedly create billions of dollars’ worth of benefits for companies.” Now, however, according to the New York Times, Japanese business organization is fast approaching the norms and practices prevailing in the US.34

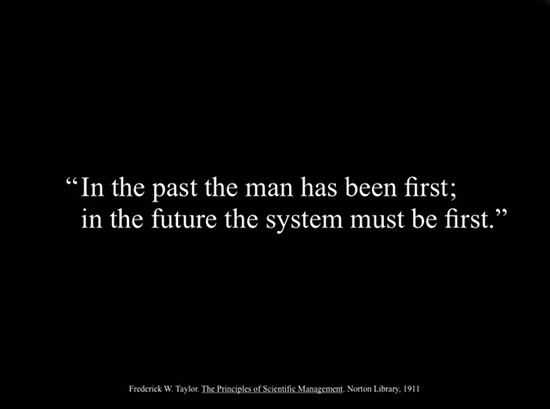

Management is always looking for a new edge; after all, managers’ advancement and compensation depend on the appearance of innovation. A few years ago, in an amusing “exposé” in the Atlantic magazine, Matthew Stewart, a former partner in a consulting firm, characterized management theory as a jumped-up and highly profitable philosophy of human society rather than an informed scientific view of the social relations of productive activities, which is how it advertises itself.35 Stewart compares the dominant theory of production known as Taylorism with that of Elton Mayo.36 Taylorism, named for the turn-of-the-twentieth-century consultant Frederick Taylor, was a method (that of motion study, which was soon married to the marginally more humanistic time study of Frank and Lillian Gilbreth) for analyzing the labor process so as to get more work out of workers.37 Mayo’s management theory, formulated somewhat later, is based on fostering workers’ cooperation. Characterizing the first as the rationalist and the second as the humanist strain of management philosophy, Stewart claims that they simply continue in these two age-old camps. Anthropologist David Graeber writes that fields like politics, religion, and art depend not on externally derived values and data but upon group consensus.38 Like many bold ideas in economics and politics, empirical inadequacy and faulty predictive power are no barriers to success. A new narrative is always a powerful means of stirring things up; as the twentieth-century Austrian psychologist Hans Vaihinger termed it in his book Philosophie des Als Ob (“Philosophy of As If”), a person needs a ruling story, regardless of its relationship to reality, and so, it seems, does any other entity or organization, especially when it requires persuasive power to obtain resources from others.39 Since the advent of neoliberalism in the 1980s, for example, those newly hired corporate heads who immediately fire about 20 percent of the workforce have been shown to do best for themselves regardless of outcome, despite the fact that this strategy has long been proven to damage a distressed company’s profitability, since it destroys corporate knowledge and working culture, if nothing else. Psychological studies are constantly being adduced to prove that many consumers are uninterested in the disproof of claims, whether for miracle cures, better material goods, political nostrums, and so on; sociologists from Merton to Adorno long ago commented in some frustration about people’s belief in luck (as in the lottery) or astrology in the face of reason. Ideology offers a powerful sieve through which to strain truth claims.

What matters, then, is not whether Florida’s bohemian index is good or bad for urban growth but that the gospel of creativity offers something for mayors and urban planners to hang onto—a new episteme, if you will. But Florida’s thesis also finds enthusiastic support in management sectors in the art world that seek support from municipal and foundation sources while pretending that the creative class refers to the arts.

European art critics and theorists, however, were far more likely to be reading Boltanski and Chiapello’s New Spirit of Capitalism, which provides an exhaustive analysis of the new knowledge-based classes (or class fractions) and the way in which the language of liberation, as well as the new insistence on less authoritarian and hierarchical working conditions, has been repurposed.40 Here is a précis, by Chantal Mouffe, addressing an American art audience in the pages of Artforum:

As Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello persuasively demonstrated in The New Spirit of Capitalism (1999/2005), the managerial class successfully co-opted the various demands for autonomy of social movements that arose in the 1960s, harnessing them only to secure the conditions required by the new, postindustrial mode of capitalist regulation. Capital was able, they showed, to neutralize the subversive potential of the aesthetic strategies and ethos of the counterculture—the search for authenticity, the ideal of self-management, and the antihierarchical imperative—transforming them from instruments of liberation into new forms of control that would ultimately replace the disciplinary framework of the Fordist period.41

This brings us to the question of authenticity and the creative class.

In the words of the American vaudevillian turned radio personality and actor, George Burns, “The secret of acting is sincerity. If you can fake that, you’ve got it made.”

In Loft Living, Sharon Zukin had already put her finger on an unanswerable paradox, namely, the simulacral effect of neatening everything up, of the desired pacification of the city, which, as I have explained, will conveniently replace difficult, unruly populations with artists, who can generally (though not uniformly) be counted on to be relatively docile.

Zukin writes:

Seeking inspiration in loft living, the new strategy of urban revitalization aims for a less problematic sort of integration than cities have recently known. It aspires to a synthesis of art and industry, or culture and capital, in which diversity is acknowledged, controlled, and even harnessed. [But] first, the apparent reconquest of the urban core for the middle class actually reconquers it for upper-class users. Second, the downtowns become simulacra, through gussied up preservation venues. … Third, the revitalization projects that claim distinctiveness—because of specific historic or aesthetic traits—become a parody of the unique.42

The search among artists, creatives, and so forth, for a way of life that does not pave over older neighborhoods but infiltrates them with coffee shops, hipster bars, and clothing shops catering to their tastes, is a sad echo of the tourist paradigm centering on the indigenous authenticity of the place they have colonized. The authenticity of these urban neighborhoods, with their largely working-class populations, is characterized not by bars and bodegas so much as by what the press calls grit, signifying the lack of bourgeois polish, and a kind of remainder of incommensurable nature in the midst of the city’s unnatural state. The arrival in numbers of artists, hipsters, and those who follow—no surprise here!—brings about the eradication of this initial appeal. And, as detailed in Loft Living, the artists and hipsters are in due course driven out by wealthier folk, by the abundant vacant lofts converted to luxury dwellings or the new construction in the evacuated manufacturing zones. Unfortunately, many artists who see themselves evicted in this process fail to see, or persist in ignoring, the role that artists have played in occupying these formerly “alien” precincts.

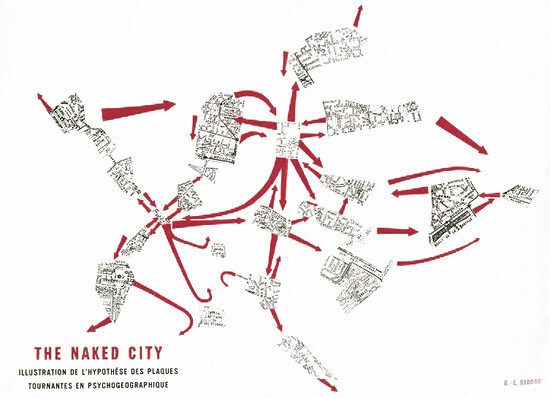

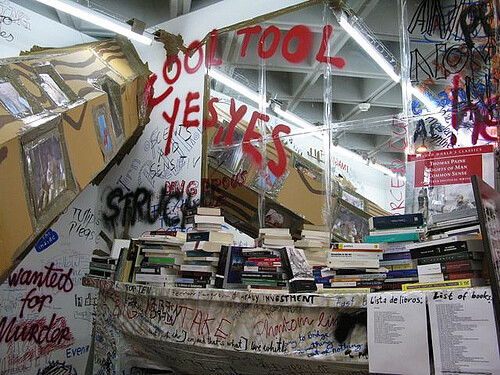

Zukin’s recent book, The Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places (2010), is aimed squarely at the lifestyle arguments typified by Florida’s work. It traces the trajectory of the idea and content of urban cool, with their repeated emphasis on those two terms, authenticity and grit.43 As she has done throughout her career, Zukin addresses the efforts of the powers-that-be to hang onto working-class cachet while simultaneously benefiting from its erasure. Zukin’s book focuses on three New York neighborhoods—the Lower East Side, or East Village; Harlem; and Brooklyn’s Williamsburg, the present epicenter of cool, walking us painfully through regional history and transformation.

Zukin also considers Manhattan’s venerable Union Square, which—with its history of parades, marches, soap-box oratory, and expressions of urban unrest and decay—has been the focus of twenty years of efforts to tame it. Zukin quotes the promotional slogan of the Union Square Partnership, a “public-private partnership”: “Eat. Shop. Visit. Union Square.”44

The Square is part of the “archipelago of enclaves” described by Dutch urbanists Maarten Hajer and Arnold Reijdorp45 as typical of new public spaces, providing, in Zukin’s words,

Special events in pleasant surroundings … re-creating urban life as a civilized ideal … [with] both explicit and subtle strategies to encourage docility of a public that by now is used to paying for a quality experience.46

Furthermore,

[T]hese places break with the past not just by passively relying on city dwellers’ civic inattention when they calmly ignore the stranger sitting on the next bench, but by actively enabling them to avoid strangers whom they think of as ”aliens”: the homeless, psychologically disoriented, borderline criminal, and merely loud and annoying .47

I note in passing that Zukin persistently faults Jane Jacobs, otherwise treated in the field as the Mother Teresa of the Neighborhood, for her own inattention to the needs and preferences of people other than the middle classes.

The disenfranchisement of those outside the groups who benefit from life in the newly renovated city is replicated in the split between the developed and less developed world; just as the paradigm of urbanism has subsumed all others, so has the globalized knowledge economy done so, and those who are not part of it are nevertheless forced to take a position in relation to it.

The postindustrial shift in Western economies from a welfare-state model to a neoliberal one has resulted in the erosion of the classical working-class base that had provided a political counterpoint during the so-called golden age of capital (1945–1970). The resulting “cultural turn,” in which conflicting claims are played out in the cultural arena—mediated through institutions that include the state, the media, and the market—represents a relocation of political antagonism to the only realm that remains mutually recognizable. In less developed economies, the global reach of aggressive consumer capitalism and the internationalization of (neo-imperialist) corporate control have provided significant challenges to the efforts of grassroots movements to secure first-world rights through political contestation. George Yúdice describes local organizing efforts of poor youth, such as Rio Funk, begun in Brazil in the 90s, and others; but he cites Brazilian commentator Antonio Muniz Sodré and Nestor García Canclini in noting that reliance on grassroots self-empowerment movements to bring about change absolves the states of responsibility and puts the burdens on the subordinated themselves.48

In considering the social presence of creative-class members in general and artists in particular, I have focused on the tendency toward passivity and complicity in questions of the differential power of others. But a significant number of artists do not fit this categorization. There is a divide, perhaps, between those whose practices are well-recognized by the art world and those whose efforts are treated as beyond the pale. I want to focus my attention here on the former group. Yúdice, concerned with the power/wealth divide, assembles an array of critical arguments, drawing on Grant Kester’s critique of the artist as service provider, always positioned from a higher to a lower cultural level, as well as Hal Foster’s 1990s critique of the artist as ethnographer.49 The problems of artists’ working in poor urban neighborhoods lie partly in the possibility, however undesired, of exploitation, and partly in a divergence in the art world audience’s understanding of the project and that of the local community, as a result of the different life worlds each inhabit. A number of artists he quotes insist that they are not “social workers” but rather seek to expand the frame of art. This suggests that intended readings must occur at least partly in terms of an aesthetic and symbolic dimension. This sits well with commentators such as Claire Bishop, who in a much-noted article winds up favoring the rather vicious projects of Santiago Sierra and those of Thomas Hirschhorn above more benign and perhaps socially useful, “service” efforts.50 Suspicious of the possible use and meaning of socially invested works, Bishop seems to regard positively the fact that the lack of social effect in Sierra’s heavily symbolic works, and the appeal to philosophical and other models in Hirschhorn’s, make them legible primarily to their “proper” art world observers. As relational aesthetics seems to be carried out on the terrain of service, it is worth noting that these works remove judgment from universal categories or the individually located faculty of taste to the uncertain and presumably unrepeatable reception by a particular audience or group (shades of Allan Kaprow!).

Yúdice joins other commentators in pointing out that art-as-service is the end of the avant-garde, removing as it does the artists’ actions from the realm of critique to melioration. In a section that has garnered some comment, Yúdice outlines how artists, even those who have looked beyond institutions and markets, have been placed in a position to perform as agents of the state. This reinterpretation of the vanguardist desire for “blurring of the boundaries of art and everyday life,” for “reality” over critique, exposes the conversion of art into a funnel or regulator for governmentalized “managed diversity.” Worse, an imperative to effectiveness has derived from arts administrators. A 1997 report for the US National Endowment for the Arts titled American Canvas insists that for the arts to survive (presumably, after the assaults of the then-newly instigated, now newly revived, right-wing driven assault on US art and culture known as the “culture wars”) they must take a new pragmatic approach, “translating the value of the arts into more general civic, social, and educational terms” that would be convincing to the public and elected officials alike:

…suffused throughout the civic structure—finding a home in a variety of community service and economic development activities—from youth programs and crime prevention to job training and race relations—far afield from the traditional aesthetic functions of the arts. This extended role for culture can also be seen in the many new partners that arts organizations have taken on in recent years, with school districts, parks and recreation departments, convention and visitor bureaus, chambers of commerce, and a host of social welfare agencies all serving to highlight the utilitarian aspects of the arts in contemporary society.51

Combine this with the aim of funding museums specifically to end elitism. In the 1990s, the federal funding agency the National Endowment for the Arts increased its commitment to “diversity” while museums, pressed by such powerful funders as the Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Ford foundations and the Reader’s Digest Fund, tried to achieve wider public “access.”52 The operative term was “community”; art was to serve the interests of “communities”—by which we must understand poor, excluded, and non-elite, non-creative-class communities—rather than promote the universalist values of modernist doctrine, which many thought simply supported the elite-driven status quo. This leaves artists interested in audiences beyond the gallery with something of a dilemma: serve instrumental needs of states and governments or eschew art-world visibility entirely.

To close this section of Culture Class, let me put into play two further quotations. From the introduction to American Canvas:

The closing years of the 20th century present an opportunity … for speculation on the formation of a new support system [of the nonprofit arts]: one based less on traditional charitable practices and more on the exchange of goods and services. American artists and arts organizations can make valuable contributions—from addressing social issues to enhancing education to providing “content” for the new information superhighway—to American society.53

And from Ann Markusen:

Artists may enjoy limited and direct patronage from elites, but as a group, they are far more progressive than most other occupational groups Florida labels as creative. While elites tend to be conservative politically, artists are the polar opposite. Artists vote in high numbers and heavily for left and democratic candidates. They are often active in political campaigns, using their visual, performance, and writing talents to carry the banner. Many sociologists and social theorists argue that artists serve as the conscience of the society, the most likely source of merciless critique and support for unpopular issues like peace, the environment, tolerance and freedom of expression.54

Markusen had in fact been asked to frame political questions by the university president himself. Markusen’s paper is centered on a critique of Florida’s creative-class thesis; see Ann Markusen, “Urban Development and the Politics of a Creative Class: Evidence from the Study of Artists,” Environment and Planning A, Vol. 38, Issue 10, 2006. See →.

I use this term here to signify ironical posers and lifestyle, particularly sartorial, devotees.

Lloyd, Neo-Bohemia: Art and Commerce in the Postindustrial City (New York: Routledge, 2006). Lloyd’s estimation of the work role of the creatives is counter to the generally benign role accorded them not only by Ray and Anderson but also by such varied commentators as Markusen and all the centrist and right-wing observers.

Zukin, Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1982).

George Yúdice, The Expediency of Culture: Uses of Culture in the Global Era (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001).

Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991), 48.

Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (New York: Routledge, 1993); Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991).

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (New York: Schocken, 1969), 217—252.

I am thinking of such US-based companies such as the phone company CREDO, which has increasingly positioned itself as a left-wing, “social justice”-oriented advocacy group that happens to sell you phone services, but also of the Fair Trade Coffee “movement” and even mainstream groups as AARP (American Association of Retired Persons) and the nonprofit magazine Consumer Reports, which sell services but also run advocacy and lobbying organizations. And then there is the religious sector, which maintains tax exemption while deeply implicated in politics.

Peter Drucker, Landmarks of Tomorrow: A Report on the New “Post-Modern” World (New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1959); Robert Reich, The Work of Nations: Preparing Ourselves for 21st Century Capitalism (New York: Vintage, 1991).

Clark Kerr, Godkin Lectures, given at Harvard University, 1963. The Free Speech Movement recognized the blueprint for the new technocratic, pragmatic, and politically disciplined and hegemonic nation, for what it was and erupted accordingly.

Clark Kerr, The Uses of the University (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963), based on his Harvard lectures, 66.

Daniel Bell, The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting (New York: Basic Books, 1973); The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (New York: Basic Books, 1976).

This note is simply to acknowledge that—no surprise here—not all labor theorists accept the term post-Fordism and its periodization of capitalist production processes, or the notion of “immaterial labor,” explored below, although they are much favored in the European art world.

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 103–115.

Lazzarato, “Strategies of the Political Entrepreneur,” SubStance 112, vol. 36, no. 1 (2007): 89–90.

Andrew Ross, “Nice Work If You Can Get It: The Mercurial Career of Creative Industries Policy,” in Geert Lovink and Ned Rossiter, eds. My Creativity Reader (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2007), 19.

Paul Fussell, Class: A Guide Through the American Status System (New York: Ballantine, 1983); David Brooks, Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000). On his website, →, Florida engages in excoriations of Brooks and presents himself as the good observer while Brooks is the bad.

Zukin, Loft Living, op. cit. See note 4. To my knowledge, the concept of the artistic mode of production was first articulated by Fredric Jameson in The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act, published in 1981, which develops the thesis of the historical grounding of narrative frameworks.

Ibid., 98.

Ibid., citing Ronald Berman, “Art vs. the Arts,” Commentary, November 1979: 48.

See, for example, Erik Olin Wright, Class Counts: Comparative Studies in Class Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure and Everyday Life (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 8.

Doug Henwood, After the New Economy (New York: The New Press, 2003).

Edward Glaeser, “Review of Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class,” 3. See →.

Ibid., 4.

Ibid., 5.

Max Nathan, “The Wrong Stuff? Creative Class Theory and Economic Performance in UK Cities.” See →.

Ann Markusen, “Urban Development and the Politics of a Creative Class: Evidence from the Study of Artists,” op. cit. See →.

Alan Blum, “The Imaginary of Self-Satisfaction: Reflections on the Platitude of the “Creative City,” in Alexandra Boutros and Will Straw, eds., Circulation and the City: Essays on Urban Culture (Montreal and Kingston, London, and Ithaca, NY: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010).

Douglas McGregor, The Human Side of Enterprise (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1960).

William G. Ouchi, Theory Z (New York: Avon Books, 1982).

W. Edwards Deming and J. M. Juran, Quality Control Handbook (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1951).

Hiroko Tabuchi, “Japanese Playing a New Video Game: Catch-Up,” New York Times, September 20, 2010, →.

Matthew Stewart, “The Management Myth,” The Atlantic, June 2006. See →.

Elton Mayo, The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilization (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1933).

Frederick Taylor, Principles of Scientific Management (New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1911); Frank Gilbreth, Motion Study (New York: D. Van Nostrand Co., 1911).

David Graeber, Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion and Desire (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2007).

Hans Vaihinger, The Philosophy of ‘As If’: A System of the Theoretical, Practical and Religious Fictions of Mankind (London: Routledge, 1924).

Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello, New Spirit of Capitalism (London and New York: Verso, 2006). This book is handy for laying out and following statistically what should be readily apparent to observers.

Chantal Mouffe, “The Museum Revisited,” Artforum, vol. 48, no. 10 (Summer 2010): 326–330. See →.

Zukin, Loft Living, 190.

Sharon Zukin, The Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Ibid., 142.

Maarten Hajer and Arnold Reijndorp, In Search of New Public Domain (Rotterdam: NAi, 2001).

Zukin, Naked City, 142.

Ibid., 142–143.

Yúdice, The Expediency of Culture; Antonio Muniz Sodré, O social irradiado: Violencia urbana, neogrotesco e midia (Sao Paolo: Cortez Editora, 1992); Nestor García Canclini, Consumers and Citizens: Globalization and Multicultural Conflicts (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001).

Grant Kester, “Aesthetic Evangelists: Conversion and Empowerment in Contemporary Art,” Afterimage 22:6 (January 1995), 5–11; Hal Foster, “The Artist as Ethnographer?” The Return of the Real (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995). See →.

Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (Fall 2004), 51–79.

Jane Alexander and Gary O. Larson, American Canvas: An Arts Legacy for Our Communities (Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts, 1997). How easily that term “utilitarian” slides into discussions of a dimension that during the Cold War was always explicitly denied →.

Yúdice, op. cit., 245.

Alexander and Larson, American Canvas. Emphasis in the original.

Markusen, “Urban Development and the Politics of a Creative Class,” op. cit., 22—23. In this paper, Markusen acknowledges artists’ role in gentrification, remarking they are “sometimes caught up in gentrification,” but she sees their role in most cities as not different from that of other middle- and working-class people migrating into working-class neighborhoods and on this account criticizes both Zukin, with whom she otherwise generally agrees, and Rosalyn Deutsche.

Category

Subject

→ Continued in Culture Class: Art, Creativity, Urbanism, Part III: In the Service of Experience(s) in issue 25.