The only positive thing about the situation in Denmark—where we have not only a riled up racist public sphere in which “foreigners” are smeared and mocked on a daily basis, but also actual race-based laws against immigrants and asylum seekers—is the certainty with which we can recognize the national democratic system as an obstacle to any kind of progressive offensive aimed at radically restructuring the wretched state of affairs at present. A first step in doing so would be to abandon any kind of confidence in the national democracy’s political forms, such as the party or the union, that still refer to the nation-state. At this point in history, the project in Denmark, and perhaps the West in general, is primarily a negative one: we must dissolve the various old, white, middle-class institutions, and stop forcing the lower classes of the world into them. We have to start over.

The Fight for the Racist Vote

But how did the situation get so bad in Denmark? Of course, it can be difficult to pinpoint the turn that enabled social democratic, conservative, and liberal politicians alike to cast suspicion on immigrants in a very brutalizing language, followed by the establishment of race-based laws. When in 1997 Poul Nyrup Rasmussen’s social democratic government named Thorkild Simonsen minister of interior affairs, explicitly assigning him with the task of making it more difficult to gain asylum in Denmark, the process was already well under way. When the Nyrup Rasmussen government was reelected the following year, the newly-created, explicitly racist right-wing Danish People’s Party, headed by Pia Kjærsgaard, gained thirteen seats in parliament. The party’s campaign was solely based on hatred of foreigners, especially Muslims, and it would repeatedly allege that Islam and Muslims sought to destroy Danish society and Denmark as a nation through immigration. “The latest figures show that there are approximately 415,000 foreigners in Denmark and that in just fifteen years there will be more than a million. We are confronted with a genuine mass-migration from the Third World,” a press release stated.1 These figures are completely wrong—in 1998 there were 195,000 immigrants from “less developed” parts of the world, according to Statistics Denmark, making Denmark one of the least “mixed” countries in Europe.

In the winter of 1998–99, the two Danish tabloids BT and Ekstra Bladet joined the “battle” and began publishing stories on a daily basis about the ways in which immigrants were “cheating” the Danish welfare system. The racist rhetoric was setting the agenda in Denmark, and the social democratic government tried yet again to conform to the new discourse by making Karen Jespersen minister of interior affairs, with the explicit aim of tightening the immigration rules. From then on, almost all parties joined the scramble for the racist votes, all arguing against immigration and referring to a loose idea that the Danish community and a very specific Danish sensibility was threatened and needed protection.

But of course, keeping up with the Danish People’s Party was difficult, as it produced increasingly demonic representations of a small, innocent Danish heaven with green pastures and smiling people being slowly demolished by the arrival of hateful and barbarian Muslim foreigners unwilling to assimilate into the Danish community and accept its values and customs. As Danish People’s Party member Mogens Camre explained in 1999, “Muslims come here with a beggar’s staff in their hands and as soon as they are allowed inside Denmark the staff is transformed into a stick whipping us into line.”2 The scene had been set. When the director of the Confederation of Danish Industry, Hans Skov Christensen, wrote a feature article in the daily Politiken in 2000 arguing that Denmark in fact needed more immigrants in order to be able to compete on the global market, he was immediately met by a storm of protests and forced to affirm his Danishness by declaring that he too hoisted the Danish flag on national holidays. Even as early as 2000, it seemed that it was already too late for Denmark. And in many respects the racist backlash was only reaffirmed in the 2001 election, when a coalition between the conservative and the liberal parties, headed by Anders Fogh Rasmussen, gained power with the support of the Danish People’s Party.

Whereas the arrival of populist and racist parties in countries like France in the 1990s had polarized the political debate, such a polarization did not take place in Denmark. Instead, all parties decided to incorporate the racist agenda, and most of the press and the media followed by reproducing aggressive racist remarks, arguing that it was a good thing to be able to debate these issues. Of course, there was no actual debate, only stigmatization and smear campaigns.

Racial Laws and State of Emergency

Then came 9/11, and all ideas about a more just redistribution of wealth between rich and poor were replaced with the so-called war on terror, enabling not only invasion wars carried out under the banner of a “clash of civilizations,” but also instituting the present state of emergency, which included a profusion of unspecified laws aimed at impeding the movements of immigration and extending networks of control and surveillance throughout Western cities. Islam has now become largely synonymous with terrorism. The election in Denmark took place little more than a month after the precision bombing of New York and Washington by enemies of the American empire, and the only topic in the election concerned not just bringing immigration to a halt, but the question of how to purge criminal immigrants—including so-called second generation immigrants born and raised in Denmark. All major parties from the Social Democrats to the Liberal Party accepted the premise that immigration was a problem or a threat. The latter launched a fierce campaign for Denmark to simply throw out immigrants or children of immigrants if they committed a crime or in any other way did not conform to the Danish way of life. One of the party’s posters showed a photo documenting a group of young immigrants of Middle Eastern origin giving the finger to the photographer while leaving a court. “Time for a change,” the caption read.

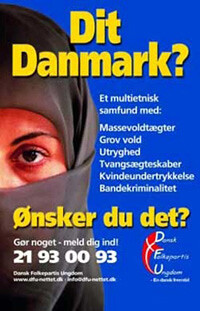

The Danish People’s Party obviously outdid the other parties in its 2001 election campaign. For instance, it published a 210-page book titled The Future of Denmark: Your Country, Your Choice; the photo on its cover depicted what appeared to be agitated Middle Eastern men carrying guns and shouting. The threat towards Danish welfare had to be visualized again and again. One of the campaign posters for the election showed an image of a smiling blond girl with the caption, “When she retires, there will be a Muslim majority in Denmark.” Another poster by the youth wing of the party showed the head of a veiled woman with the text, “Your Denmark? A multiethnic society with: Gang rapes, violence, insecurity, forced marriages, repression of women, gang crimes. Do you want that?” Nevertheless, the party was welcomed into the sphere of power and participated in formulating the new government program, making sure that immigration to Denmark would become nearly impossible thereafter.

The election in 2001 was historical because it became possible to form an exclusively right-wing government supported by the populist and extreme right-wing Danish People’s Party, neutralizing the role of the small center parties that usually take part in forming a new government in Denmark (these parties had unsuccessfully tried to avoid the most strident racist rhetoric while still accepting the general trend towards anti-immigration and xenophobia). The first in a long and seemingly never-ending series of laws hindering immigration saw the light of day in 2001, and made it extremely difficult for someone living in Denmark to bring their “non-Danish” partner to Denmark. Soon after, the government and the Danish People’s Party introduced the so-called Start Help unemployment assistance program, making out of work immigrants receive a significantly lower transfer income than that of “real Danes.” The UN Refugee Agency and the EU protested, but the criticism was rejected and since the Danish press had recently normalized the new discourse, such “external” critique was presented as irrelevant or as a genuflection for suspicious multicultural ideas that did not yet comprehend the threats of totalitarian Islam.

When political phenomena like the rise of right-wing populism in Europe is addressed in Danish media, the Danish People’s Party is rarely mentioned. Jörg Haider, Jean-Marie Le Pen, and Geert Wilders are given as examples, but Pia Kjærsgaard is not. Racism has simply become the norm for Danes. Racism? No, just a healthy and outspoken relationship with the problems connected with immigrants and foreigners. In less than ten years, Danes slowly grew accustomed to seeing foreigners as threatening and subhuman, as those who could be not only repressed, but also persecuted. Globally, it is, for the most part, the bombed and butchered Palestinian refugees that have had to bear the brunt of this development, while the Western middle classes are trained in racism.

The launch of the defense of Denmark against Muslim immigration was just one component of the new liberal right-wing government’s politics. Another consisted in siding with George W. Bush and his war on terror. The Danish government was always there next to Bush, from the invasion of Afghanistan to the occupation of Iraq—and Danish troops are still present in Afghanistan. The Danish participation was a dramatic change from the significantly less active role the Danish military played on the global scene during and after the Cold War. That the invasion of Iraq was based on lies—there were no weapons of mass destruction or terrorist cells in Iraq—never became a matter of discussion in Denmark. The government and the Danish People’s Party have so far managed to silence all criticism by presenting criticism of the war on terror as synonymous with support of the terrorists.

Authenticity Totalitarianism

The collaboration between the liberal right-wing government and the People’s Party effectively confirmed the transformation of politics in Denmark into what we might term national democratic authenticity totalitarianism, a peculiar mixture of democracy, racism, and fascism, primarily expressed as a cultivation of Danish authenticity and hatred of foreigners. All that is seen as foreign to Danish values is presented as a threat, from al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and Saddam Hussein and his Baath Party, to local immigrants wearing veils and the non-parliamentary left wing. They are all security risks that must be handled—by preemptive measures, if necessary.

Newspaper ad by the right-wing party Venstre with the caption: “A immigration policy that is both fair and firm,” 2001.

In 2003, the government launched a genuine campaign against Muslims, urban youth culture, the so-called cultural elite, and anything seemingly left-wing. The Fogh Rasmussen government labeled the campaign a “battle of culture” and argued that it was necessary to protect Denmark against multiculturalism, Islam, and the left. A canon of “Danish” values was subsequently drafted and made obligatory reading in schools. And canons of Danish art, literature, music, architecture, and film were also produced and circulated with great fanfare. The minister of culture, Brian Mikkelsen, talked about the existence of “a medieval Muslim culture” in Denmark that had to be eliminated, and Fogh Rasmussen stressed the need to protect Western values militarily as well as culturally. Groups that somehow did not fit the dominant vision of Danish identity were in for a hard time. The Muhammad drawings from 2005, in which the right-wing daily Jyllands Posten mocked local Muslims, and the eviction at the Youth House in Copenhagen in 2007, where a viable youth culture was deprived of a semi-autonomous space, were the most visible signs of this campaign against alternative ways of life in Denmark.

As the raiding of the Youth House shows, the xenophobic campaign against Muslim immigrants was accompanied by an attack on the left. According to the government, the country was in need of a cleansing of the old leftist and 1968 ideas that threatened to destroy the Danish community in favor of a multicultural society. To an unprecedented extent, the government pressured public institutions like state television and the university system to distance themselves from what were perceived to be dangerous ‘68ist currents. The demonization of left-wing ideology continued in the ongoing dismantling of the welfare state, with healthcare, education, and research budgets being seriously cut—a move that has been further intensified with the financial crisis, which the market-liberal right-wing government has, with its supporting party, seized upon as a favorable window of opportunity.

Excessive use of violence and the criminalization of formerly accepted expressions and actions were also the order of the day. During the fights that broke out after the brutal raiding of the Youth House on May 1, 2007, the police took a strong line against the protesters and imposed visitation zones in several districts of Copenhagen, searching thousands of people unlikely to have done anything of a criminal nature. On several occasions during the last few years, immigrants have been charged with planning terror attacks and officially expelled from Denmark without legal trial, due to security reasons known only to the secret service and the minister of justice. Lawyers and human rights groups have protested, but the critique of these incidents has been easily rejected as naïve, referencing the threats circulated by the government’s politics of fear.

Foreigners and Modern Art

These local developments were, of course, linked to the global process that for a period was named “the war on terror” but in effect constituted an extensive neoliberal counterrevolution expanding a closely-defined capitalist power base by combining liberal market economy with emergency laws—the same meeting of liberalism and right-wing populism that became the norm in the Western world since 2000. Although there were differences between the emergency neo-liberalism of George W. Bush, Tony Blair, Silvio Berlusconi, and Fogh Rasmussen, the overall pattern was pretty clear: tax releases for the wealthy went hand in hand with a kind of stylistic demagoguery and a provocative emphasis on the dangers against the national community lurking everywhere, but from foreigners and Muslims especially. Looking back on this period from 2000 to 2008 one might describe this mixture—that also included a very conscious use of religion—as liberal Bonapartism following Marx’s description of the post-republican Louis Bonaparte and his regime.

One might argue for making a connection between the present Danish liberal state racism and different populist movements of the 1960s and early 1970s in Denmark that expressed hate and resentment towards foreigners and modern art. The so-called Rindalism (named after Peter Rindal, a warehouse manager from Herning) attacked experimental art and the newly-created Danish Arts Council for its support of the period’s abstract and conceptual art. Rindal saw the Danish Arts Council’s activities as scandalous for using state resources to support incomprehensible and strange art. The opposition against modern art was articulated in explicit nationalist terms where modern art was considered to be foreign and a threat to the healthy values of ordinary Danes. Rindal’s resentment and anger gained further ground in the election in 1973, when two new anti-state and xenophobic protest parties gained seats in parliament through campaigns complaining that the state was becoming increasingly large, colonizing people’s lives, and even spending money on meaningless art.

The mistrust of art, or at least experimental art, is still an ingredient in the politics of the Danish People’s Party. The leader of the party, Pia Kjærsgaard, is no great fan of modern and contemporary art. In one interview she clarified her position, stating that “two naked men running around on a stage saying pling [sic] is not art.”3 Art should educate people about Danish democratic values rather than create problems, Kjærsgaard explained. The party has therefore used its influence to secure money for the preservation of various Christian monuments in Denmark, as well of the home of the nationalist writer Kaj Munk. In accordance with this agenda, the liberal right-wing government has pressed, as we have seen, for a nationalist implementation of art, restructuring support for the arts according to a new public management discourse by which art is measured in economic terms and used to promote tourism in Denmark. These developments were, of course, similar to what took place in many other Western European countries during that period.

Resistance

There has been very little resistance to these developments in Denmark since the late 1990s. Few dissidents have made their voices heard, and often they have had difficulties voicing their views in the subservient Danish media, and have had to establish alternative networks and journals, which are often hard to keep running. During the last three years, where the government and the Danish People’s Party have continued to find new ways of tightening the already extremely severe immigration law, a number of grassroots activities have nevertheless appeared. In 2007, a group called Grandparents for Asylum started demonstrating in front of the Sandholm refugee camp outside Copenhagen, and continue to do so today. In 2008, a large demonstration mostly composed of youths from the Youth House movement tried to close down the Sandholm camp and engaged in fights with the police as they tried to tear down the fence surrounding the camp, where asylum seekers have been kept for years. The huge amounts of teargas used by police to contain the protesters has been harshly criticized, even by political parties and media experts who have previously commended their containment of protesters. In 2009, a group of sixty rejected asylum seekers from Iraq—a country Denmark had invaded along with the US and the coalition of the willing, displacing more than four million Iraqis—sought refuge in a church in Copenhagen, fearing for their safety upon returning to Iraq in the midst of a civil war. A group calling themselves Church Asylum supported the immigrants and tried to prevent the church from being raided, which took place on the night of August 13, 2009, with a massive police force.

The most potent protest movement has surely been the movement that manifested itself after the raiding of the Youth House on March 1, 2007, when thousands entered the streets protesting and fighting the police. For more than a year a demonstration took place every Thursday until the municipality of Copenhagen decided to give the movement a new home. The welfare cuts that have been a permanent item on the liberal right-wing government’s agenda have also occasionally been met with demonstrations. In 2006, more than a hundred thousand people protested in Copenhagen against the “new necessary measures” for securing the Danish economy. But until now it has been very difficult to make connections between protests against racial laws and demonstrations against welfare cuts. Anti-racist and anti-war resistance have rarely fused with a critique of the government’s neoliberal policy. And of course that is also a part of a more general picture in the Western world, where there is no coherent resistance. There seems to be a wide abyss between the street and the shop floor, and the sporadic militancy of the street is rarely able to spread to other places. Apparently, it is not possible to formulate a coherent critique whose individual objects are joined together in a radical critique of the capitalist system assuming the form of money and state.

Beyond the National Democracies

Looking back on these developments in Denmark, it is clear that the Danish People’s Party played a leading role in the racist turn that took place, but it would be foolish to analyze the shift by looking exclusively at that particular party. It is also necessary to look critically at the national democracy as a structure that carries within it the possibility of exclusion and racialist tightening when large parts of the population experience fear and lack of direction, as was increasingly the case with the process of globalization. The meaninglessness of capitalism, in which we reproduce the world each day but feel devoid of agency and control over our life, calls for the nation-state to momentarily stop constant deterritorialization and glue society back together again. And that operation increasingly take place through exclusion. One of the best descriptions of the process in which national democracies turn racist can be found in Hannah Arendt’s analysis of the large-scale migration movements after World War I as having exposed the mechanisms of exclusion inherent in the nation-state, opening the possibility for the Nazi regime to transform Jewish Germans into stateless subjects deprived of any rights and ready for elimination.4 We might not be there yet, but as the late Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe warned when confronted with the rise of Le Pen, we are in a state of urgency, because racism can cause matters to escalate quickly from repression via persecution to elimination.5

What is to be done? The tools to develop enemy-focused internal self-management are far superior today to even what Debord foresaw, and this tends to render former revolutionary slogans obsolete. It is difficult to see a subversive international subject anywhere preparing to push, rebel, and abolish wage labor, the money economy, and the state, but at least things are starting to stir a bit in places like Athens and Dhaka. Only time will tell whether the anger and meaninglessness will be picked up by counter-revolutionary dynamics or develop into a real alternative. Let us hope it will, and let us do all we can in the meantime to dissolve the national democracy that is not, as Lenin argued in 1920, an empty shell (to be used by communists agitating for revolution), but something that involves the population and leaves its stamp on it.6 In the present situation, perhaps that would amount to half a revolution.

The Danish People’s Party in Jyllands-Posten, September 5, 1998.

Mogens Camre in Information, October 24, 1999.

Pia Kjærsgaard in Information, December 12, 2007.

See Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1973).

Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe: “Nous sommes dans l’urgence,” Lignes, no. 31, 1997.

Vladimir Lenin, “Should We Participate in Bourgeois Parliaments?”, Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder, originally published in 1920 in Russian, English, French, and German, available at →.