Season’s Greetings from Sarrazin

In its 2010 Christmas Eve issue, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung had a special gift for its readers. The reputed conservative newspaper opened its cultural pages with an article penned by Thilo Sarrazin, a former German Federal Bank executive and member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) who seized the opportunity to muse on the incidents of the past months. His book Deutschland schafft sich ab (Germany Does Away With Itself) had been published in late August 2010, and was benefitting from massive support by high-circulation media such as the tabloid Bild and Der Spiegel, which had printed excerpts from the book in advance. The book sold about 1.2 million copies and became the best-selling non-fiction book on the politics of the past decade.1 In his article, Sarrazin boasts of having almost caused a crisis in the German state. Certainly, his 464 page diatribe against the failure of the welfare state, multiculturalism, and in particular against Muslim immigrants and their alleged reluctance to “integrate,” spiced up with demographic statistics and eugenicist speculations on “race” and “intelligence” had made the man the most loved and hated voice (and face) of a populist vibe running rampant throughout the country. And these feelings are shared by millions of (largely middle-class) Germans who not only indulge in increasingly unfettered resentment against immigrants, the unemployed, and the working poor, but also unite around the collective blaming of the political class and the media for having failed to sort out the “problems” of demographic change and economic crisis.

The deprecating responses his book prompted among leading politicians, from Chancellor Angela Merkel to President Christian Wulff, but also among his fellow Social Democrats and the majority of media commentators, amounts—according to Sarrazin’s Christmas Eve dispatch (full of self-congratulatory “contempt”)—to the perceptions of a threatening “cartel of political correctness” common among “citizens” who, thanks to the debate instigated by his blockbuster, are finally empowered to ask the very questions that “have been for a long time confined to political discourse.”

Freedom Fighters

Sound familiar? Perhaps it does, because such a critique of “political discourse” is utterly familiar populist discourse. Accusing a putative leftist hegemony of ruling by means of undemocratically-imposed “politically correct” lawmaking has been populist stump speech for quite some time. However, things don’t stay the same even if they sound or look as if nothing has changed since the last time it seemed necessary to contest the right-wing idea of political correctness as the enemy of free speech. As odd as it may seem for Viennese art critics Matthias Dusini and Thomas Edlinger to have recently announced that they will work on a book on political correctness, this announcement seems to reflect a renewed desire to attack what is perceived as an overregulated and disempowering discourse backed by unquestioned consensus. Dusini, a regular contributor to Springerin and the art editor of the leftist Vienna city newspaper Falter, already made his stance on political correctness available in a commentary published in the Der Standard newspaper. Rhetorically, he asked why a former Bundesbank executive such as Sarrazin, or, for that matter, Kadri Tezcan, the Turkish ambassador in Vienna who publicly criticized Austrian immigration policy, have become the real taboo-breakers of our time, whereas contemporary artists and curators, afraid to violate the rules of politeness and political correctness, of “the language of anti-ziganism, anti-racism, anti-sexism, and anti-homophobia,” don’t dare “to call a spade a spade.”2 Deploying the well-known discursive strategy of addressing contemporary art as some general and homogeneous whole that lacks the courage to act according some idea of “art” that requires no further explanation, Dusini willfully joins the ranks of those populist critics who yearn for an art that is wild and angry, non-conformist to the core, and therefore automatically immune to the temptations of a self-indulgent, presumably leftist blindness to the real challenges society is facing.

The reasons for this alleged blindness are well known among the ideologues of the old new right. Norbert Bolz, a German philosopher who came a long way from Walter Benjamin scholarship, postmodern media theory, and his “consumerist manifesto,” to current self-declared intellectual leadership (assisted by fellow thinkers such as Peter Sloterdijk, Robert Spaeman, or Udo DiFabio) over a tremor of allegations about leftist hegemony, provides valuable, if ultimately unsurprising, insight into the workings of the neoconservative mindset. As Bolz has it:

Our society that is incapable of an orientation provided by religion, bourgeois tradition, and common sense [gesunder Menschenverstand] becomes the limp victim of a terror of virtue [Tugendterror] bred in universities, editorial offices, and anti-discrimination offices.3

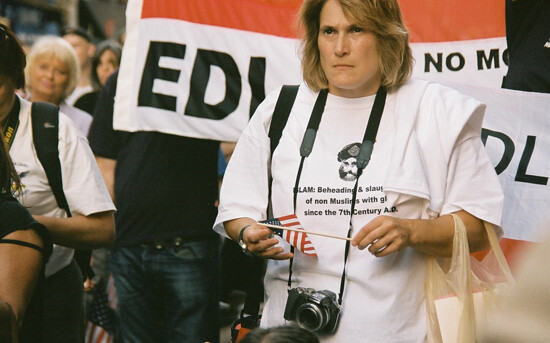

And he leaps even further back in history, that is, back to Luther, who in his time preached spiritual freedom in political servitude, whereas “today we have spiritual servitude in political freedom.” The phantasm of being governed by a specifically insidious leftist scheme that pretends to garner the ideas of justice and equality but actually aims at limiting the freedom of individual self-expression, is standard coinage of populist discourse. “Freedom” is invoked whenever freewheeling vox populi seems to be restrained by a politics emphasizing the right to having rights, particularly those of minorities, instead of catering to the desires of an alleged majority. The relative frequency of neo-right-wing parties that have opted for “freedom” or “Freiheit” as their moniker is telling in this respect, as we have seen it in the case of the alarmingly successful Austrian FPÖ (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs) and the recently founded, Berlin-based “Die Freiheit,” assembled by former members of the CDU (Christian Democratic Union) and the libertarian “Piratenpartei” (and is quite ostensibly modeled after Geert Wilders’s “Partij voor de Vrijheid”). At stake, however, is the “freedom” of those who are united against an alleged “Islamification” of society (that is, the nation) as well as against the (Keynesian or other) revival of “the state” in times of economic and ecological crisis. Hence, forces of destruction and demise such as “immigrants,” “Islam,” “welfare state,” “multiculturalism,” “political correctness,” and “politicians” are being identified in order to activate what can be easily perceived as “resistance,” “disobedience,” or even “rebellion.” As war is declared on “freedom,” freedom fighters are to be recruited among the citizenry. This is populist, but also neoliberal logic, since the fantasy of freedom is nurtured by ideologues of a nationalist-culturalist right wing, as well as by proponents of economic deregulation and the liberty of consumption. Most predictable but always effective, defending one’s own “freedom” is the most justifiable way of curtailing that of others.

“Wutbürger” or Active Citizen?

An appropriate name has not been found for the phantom majority this battle for “freedom” fights for, but it may be a very familiar one in the end. A semantic shift probably as interesting as the appropriation of the liberalist idea of “freedom” by the New Right occurred around the figure of the “citizen” (Bürger). Transcending (or suppressing) the otherwise useful distinction between citoyen and bourgeois, the German “Bürger” always worked as an ideologically malleable signifyer. The current usages of the word oscillate between populist appropriations of “bürgerlich,” as an attribute of anti-statist, anti-PC, anti-welfare positions of self-entitled bourgeois top-performers (“Leistungsträger”) such as Bolz’s on the one hand, and the phenomenon only recently known as the “Wutbürger” (angry citizen) on the other. Not by chance, the very term “Wutbürger” won the German Language Society’s award for the “word of the year” in 2010. It is the denomination chosen for a social figure said to constitute something that is not yet a national movement (though the media work overtime to turn it into one), but a motley bunch of local phenomena engendering the social differences of an alleged “Dagegen-Republik” (Der Spiegel). Primarily instigated by the protests against the demolition and subsequent modernization of Stuttgart’s central train station (protests held by a heretofore unlikely rainbow-ish coalition of seniors and youths, of middle and upper class, of environmentalists and commuters, who for months demonstrated on the streets of a city that hasn’t undergone any significant public display of civil unrest and disobedience for decades), the “Wutbürger” is an indication of indignation and the (mainly middle class–driven) firm belief that the political and economical leaders have failed to do their jobs and have to be confronted with (if not complemented by) the knowledge and willpower of the citizenry.

In his New York Times op-ed in identifying three main traits of the current German populism, racism, rejection of professional politicians, and bottom-up mobilization, Jürgen Habermas pointed out that

The motivations underlying each of the three phenomena—the fear of immigrants, attraction to charismatic nonpoliticians and the grass-roots rebellion in Stuttgart—are different. But they meet in the cumulative effect of a growing uneasiness when faced with a self-enclosed and ever more helpless political system. The more the scope for action by national governments shrinks and the more meekly politics submits to what appear to be inevitable economic imperatives, the more people’s trust in a resigned political class diminishes.4

Language of the “einfache Menschen”

Among the charismatic non-professionals in politics Habermas had in mind, Joachim Gauck features prominently. A former civil rights activist in the GDR who in 1990 became the first director of the Federal Commission for Stasi Documents, Gauck has been nominated in 2010 as the candidate of both the Social Democrats and the Green Party for the office of Bundespräsident, president of the Federal Republic. Though he eventually lost the elections to Christian Wulff, the candidate of the current conservative-liberal government, Gauck’s campaign made a lasting impression on public opinion. As an outsider not affiliated with any political party (in spite of conservative leanings), eloquent and fairly media-savvy in the role of the quintessentially independent mind who dares to touch on the weaknesses and bigotries of the system, Gauck quickly became a popular figurehead of a brand of fringe conservatism emerging from amidst middle-class society.

Hardly as non-conformist as he and his admirers may wish him to be, however, Gauck—in good opportunistic spirit, considering the widespread dissatisfaction with political discourse—calls for the citizen’s increased involvement in political matters and demands that politicians use a language the “einfache Menschen” would be able to understand. For an example of such clarity of discourse, Gauck recommends listening to Sarrazin, who, in his view, has proven courageous in speaking directly to those issues that politicians tend to avoid. Sarrazin’s success therefore is testament to the fact that the “language of political correctness,” as deployed by the members of the political class, contributes to the inevitable feeling that “the real problems shall be obscured.”5

For Gauck and those who help to distribute such statements, the “real problems” seem to be unequivocally decided upon—as are the ways to go about addressing them. The truth and authority of Sarrazin’s poorly-organized and poorly argued book seem to have already been proven by the very number of copies sold. Each purchased copy increases its symbolic value as a manifesto of the enraged rebel citizen, who, as fictional and manufactured as she or he may be, has in 2010 become the spectral figure haunting the political scene. In the wake of the financial crisis, the erosion of the Eurozone, climate change, demographic developments, and other creeping catastrophes (experienced as quasi-natural disasters nevertheless prompting utterly culturalist reactions such as Islamophobia), the angry rebel citizen insists on her or his right to be “free” of constraints and fears that impede her or his individual status, security, privileges, wealth, mobility, and so forth—all of which grow even more strongly cherished as they are come to be shared by a (imagined) community of belonging. Thus, the implicit lesson of Sarrazin’s book and the debates in the aftermath of its publication has been that defense of these seemingly endangered individual and communal rights is in order: become an “active citizen”!

The emerging counter-political class—the new “APO” (extra-parliamentary opposition), as some commentators have had it—rhymes well with a neoliberal, neo-nationalist governmentality of deferred responsibility in which individuals are told, often by state officials, to no longer rely on the state, but on themselves. Being “responsible” in this sense is to mistrust the traditional systems of governance and begin self-organizing, both individually and collectively. Moreover, such “responsible” behavior will transcend self-interest and include leitkultur, “democracy,” or the “Judeo-Christian” tradition in the rebel citizen’s roster of duties. Here, however, the limits between volunteer work and vigilante justice, between direct, plebiscitary democracy and an anti-democratic delegitimation of the state become increasingly blurred. The contemporary cocktail of political projects is composed of seemingly incommensurable ingredients. Thus, contesting and de-articulating the current confusion of vocabularies (of emancipation and exclusion, freedom and racism) seems to be the most urgent priority.

Thilo Sarrazin, “Ich hätte eine Staatskrise auslösen können,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, No. 300, December 24, 2010, 33.

Matthias Dusini, “Neo-Avantgardisten der Höflichkeit?,” Der Standard, November 24, 2010. See →.

Norbert Bolz, “Die neuen Jakobiner,” Focus, No. 37, September 13, 2010. See →.

Jürgen Habermas, “Leadership and Leitkultur,” New York Times, October 29, 2010. See →.

Quoted from Stephan Haselberger/Antje Sirleschtov, “Runter vom Sofa. Ex-Bundespräsidenten-Kandidat Gauck wünscht sich Bürger statt Politikkonsumenten und lobt Sarrazin,” Der Tagesspiegel, No. 20844, December 31, 2010, 4.