In the last three months I’ve been organizing a series of public seminars at CUNY Graduate Center on “deskilling” in the arts since 1945, and in the article that follows I may have undergone some deskilling myself—from an art historian/critic who writes about art to a commentator on cultural policy. I apologize if the results are bland, bureaucratic and statistical; I’m finding my feet here. In what follows, I will argue that in the wake of the general election in May 2010, which resulted in a Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition—the UK’s first coalition government since 1945—the ensuing cuts to culture cannot be seen as separate from an assault on welfare, education, and social equality. The rhetoric of an “age of austerity” is being used as a cloak for the privatization of all public services and a reinstatement of class privilege: a sad retreat from the most civilized Keynesian initiatives of the post-war period, in which education, healthcare, and culture were understood to be a democratic right freely available to all.

1. Background: Culture

In the UK, public funding for the arts is administered by Arts Council England via a government body called the Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). Following the change of power in May 2010, the DCMS asked Arts Council England to take a 29.6 percent cut to its budget. This translates as a cut from £449 million for the arts each year, to £350 million—the biggest cut to the arts since government funding began in 1940. In the years that followed, public expenditure on the arts was established with a mandate to promote the accessibility of culture to the British public and to operate at an “arm’s length” from government policy (an autonomy principle typical of the Cold War period).

In recent decades, the Arts Council’s “arm’s length” policy has been severely strained, and particularly so since the neoliberal turn of Thatcher’s Conservative government (1979–1997), and again under Blair’s and Brown’s New Labour government (1997–2010). Both parties instrumentalized culture, but to different ends. Detecting that the arts were a vehicle of dissent, Thatcher enforced a populist, profit-making model: weaning culture off a welfare-state mentality and encouraging an entrepreneurial approach in which “bums on seats” became a more important criterion than “ideas in the head.”1 The shift did not close down culture but led to some powerful expressions of resistance, especially in film and theatre—even if the popular successes of this period were primarily musicals by Andrew Lloyd Webber. New Labour also viewed culture as an economic generator, but in a different fashion, recognizing the role of creativity and culture in commerce and growth in the “knowledge economy.”2 This included museums as a source of regeneration, but also investment in the “creative industries” as alternatives to traditional manufacturing.3 As such, New Labour adopted a far more openly instrumental approach to cultural policy than previous UK governments, and this extended to intervening in the National Curriculum to facilitate the development of creativity within schools as an equal to literacy and numeracy.4 They also introduced free admission to all museums, which—along with the Turner Prize, Saatchi’s collection, and the opening of Tate Modern in 2000—generated a massive popular audience for the consumption of culture in Britain. Labour advocated greater public participation in the arts, sought to develop culture in the regions, and to support the training and integration of black and ethnic minorities into positions of cultural power through positive action “cultural diversity” schemes.

Labour’s commitment to creativity was such that a Green Paper from 2001 even opens with the words “everyone is creative,” presenting the government’s mission as one that aims to “free the creative potential of individuals.”5 However, it is important to recognize that this aim of unleashing creativity was not designed to foster greater social happiness, the authentic realization of human potential, or the utopian imagination of alternatives, but rather to accelerate the processes of neoliberalism. In the words of sociologist Angela McRobbie, it aimed to produce “a future generation of socially diverse creative workers who are brimming with ideas and whose skills need not only be channeled into the fields of art and culture but will also be good for business.”6 In short, the emergence of a creative and mobile sector minimized reliance on the welfare state while also relieving corporations of the burden of being responsible for a permanent workforce. As such, it became important to develop creativity in schools, not so that everyone could be an artist (as Joseph Beuys declared), but because the population is increasingly required to assume the individualization associated with creativity: to be entrepreneurial, embrace risk, look after their own self-interest, be their own brands, and be free of dependence on the state.7 To cite McRobbie once more:

the answer to so many problems across a wide spectrum of the population—e.g. mothers at home and not quite ready to go back to work full time—on the part of New Labour is “self employment,” set up your own business, be free to do your own thing. Live and work like an artist.8

But the present-day government has no such plan for perpetuating creativity as a cornerstone of the “knowledge economy,” as can be seen in the depth and types of cuts it has prioritized, in culture but more importantly in education (as I will discuss below). For example, it has disbanded Creative Partnerships, an organization dedicated to developing the creative capacity of individuals by employing artists, poets, writers, and musicians to work with schools and teachers in the most disadvantaged communities. It has also axed A Night Less Ordinary (which offered free theatre tickets to people under 26—a student body already faced with a hike in tuition fees) and Find Your Talent, two initiatives that encourage young people to participate in cultural activities. The educational charity Creativity, Culture and Education (CCE) will have its budget halved to £19 million; it too provides access to the arts for children in over 2,500 schools. The underlying class agenda here is not difficult to detect. The middle class always finds a way for their children to take part in the arts, but children from poorer households require the assistance of state subsidies, which are precisely what is being cut.

2. Culture Since May 2010

The funding cuts imposed on the DCMS by the Tory–Liberal Democrat coalition have occasioned a surprisingly concerted opposition from artists. Over 100 of them—including 19 Turner Prize winners and 28 previous nominees—signed a public letter to the Culture Secretary Jeremy Hunt (head of the DCMS). In it, they express concern for the fact that smaller museums and galleries, especially regional ones, will be worst hit, making the important point (true also for myself) that “many of us had our first inspiring encounters with art in these places.”9 In a letter to The Guardian, Patrick Brill (aka Bob and Roberta Smith) referred to the cuts as “an unprecedented war on culture,” while Tate director Nicholas Serota has described them as operating with “the ruthlessness of a blitzkrieg.”10 Depressingly, the chief executive of Arts Council England, Alan Davey, was in vocal support of the cuts, claiming that “it’s something we would have wanted to do anyway.”11

In the midst of all this, it is worth remembering that in March 2007, the previous Labour government diverted £675 million from the arts to pay for the Olympics.12 But New Labour was also (in)famous for its numerous “quangos”—governmental agencies that acted as independent bodies of expertise and funding, but were perceived by many on the right to be draining financial resources. Under the new regime, dozens of quangos have been abolished, including the Council for Architecture and the Built Environment (which advised on long-term urban planning and design), the UK Film Council, and the Museums, Libraries, and Archives Council. The list of organizations to suffer cuts also includes eight small museums not decreed to be “national institutions”; their funding will be entirely halted by 2014–15, with the understanding that they “should be the responsibility of local communities.”13 These include the Horniman Museum—a gem of a time warp in South London with an insane taxonomy collection that finds space even for a pickled mermaid—which will lose 85 percent of its budget. The Geffrye Museum, an exquisite collection in Shoreditch devoted to interior design since 1600, will lose 75 percent of its budget. Three museums outside London will also see their funding grind to a halt: the People’s History Museum in Manchester, the Museum of Science and Industry (also in Manchester), and the National Coal Mining Museum (in Wakefield). These latter cuts are perhaps the most telling, because they reveal the government’s bias towards depoliticized forms of high culture. To cut the People’s History Museum is to effectively de-institutionalize the working class’s own history and ensure that its narrative will be presented by the victors.

Axing funding to these institutions inevitably sends the message that such museums are dispensable, and that only commercially viable museums can continue to operate—a market-based logic that now looms over the country’s entire cultural and educational future. The National Theatre (which receives £19.7 million annually from the Arts Council) has already secured £10 million from Travelex, while Mastercard has stepped in to sponsor the South Bank Center’s 60th Anniversary of the Festival of Britain. This kind of corporate funding is not available to regional, less high-profile and less glamorous institutions, and moreover impedes long-term planning even for those who do manage to secure it.14 Arts Council England was told to pass only 15 percent of the cuts to “front-line” arts organizations—in other words, to preserve wherever possible the funding for “central” organizations in London (Royal Opera House, English National Opera, The Royal Ballet, the National Theater), which also happen to be the institutions that find it easiest to attract corporate and individual patronage, and whose ticket prices are the most prohibitively expensive to those on an average wage and below.

One of the Arts Council’s new goals is to promote private philanthropy—but the UK lags far behind the US in this field. Although John Sainsbury has given a £25 million donation to the British Museum, and in 2008 the dealer Anthony d’Offay sold his £125 million collection to the Tate and National Galleries of Scotland for £26.5 million, these are isolated instances, since Britain lacks the philanthropic mentality that characterizes the US. While the US system is held up as a model, the fact that it is tied to the fortunes of the market means that it’s currently experiencing a 35 percent drop. Jeremy Hunt has offered to match £80 million of private donations with £80 million from the government over five years, yet this money has already been promised to organizations from the National Lottery, so it’s hardly a generous offer.15 Additionally, the UK has no tax incentive to encourage private philanthropy, since donors do not receive the tax break, only the charities (unlike the US, where private individuals gain from giving).

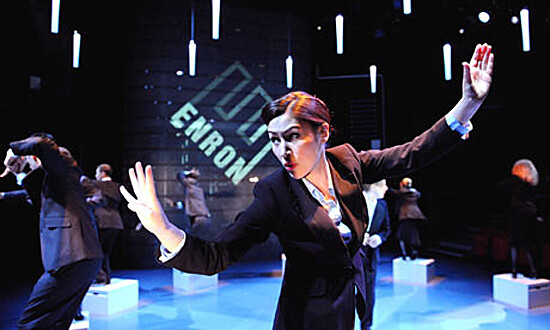

Even if incentives were in place, there is little to be said for the cultural benefits of a move to private and corporate funding. As can be clearly seen in the US, private funding hinders creativity and risk-taking, and promotes a blockbuster mentality that serves the patrons first and culture second; social status trumps cultural vitality every time. Some productions are fatally unattractive to sponsors: one of the most widely cited in defense of UK public funding has been Lucy Prebble’s Enron, a hugely successful play about corporate greed that began as a small-scale regional production before making it to London, and eventually Broadway. My experience of cultural funding in New York is that experimental projects rarely receive support, while private sponsorship encourages self-censorship and the triumph of market imperatives. But a deference to big business is explicitly being encouraged in the UK: another of the Arts Council’s stated new targets is to pay heed to the Foreign Office’s emerging power priorities (China, India, Brazil, Gulf states, Russia, Japan). The message seems to be that there’s funding for Chinese art (which paves the way for international commerce), but not for local history. And the latter will have to be looked after by the local populace, rather than valued as national patrimony.

Such a reliance on local volunteerism is of course exemplary of what David Cameron calls the “Big Society”: ostensibly, a form of people power in which the public can challenge how services like libraries, schools, police, and transportation are being run, and potentially take them over (talk about deskilling!). Pitched as a “dramatic redistribution of power from elites in Whitehall to the man and woman on the street,” the Big Society is basically a laissez faire model of government dressed up as an appeal to foster “a new culture of voluntarism, philanthropy, social action.”16 It’s a thinly opportunist mask: asking wageless volunteers to pick up where the government cuts back, meanwhile privatizing services crucial to education, welfare, and culture.17 The Big Society is just another word for sacrifice: responsibility is devolved downward, and Jeremy Hunt (with a personal fortune of £4 million) tells us we all need to dig deeper to fund culture. The biggest sacrifice of all is demanded of the lower classes, who are the hardest hit by an “age of austerity” prompted by an obscenely reckless deregulated banking system, its bailout by the taxpayer, and exacerbated by Britain’s commitment to the 2012 Olympics.18

3. Privatizing Education

Ah, the Olympics. One of the many decisive moments in my departure from the UK higher education system in 2008 was the depressing diversion of funding away from postgraduate education to subsidize the 2012 Olympics. At the same time, it was one of Labour’s goals to get 50 percent of the population into higher education by 2010 (they failed; it remains somewhere in the 40s). This could only be done by making higher education a more commercial operation, and resulted in a constant pressure to accept more students (especially those from non-EU countries who pay the highest fees) and a culture of administration and accountability that decimated faculty energy for research. Accompanying this was a foreclosure of academic freedom: individual grants for doctoral study in the arts and humanities—already scarce and highly competitive—were replaced by thematic “block grant funding” running across several departments, so that prospective postgraduates would have to fit their proposed research area into predetermined themes. Faculty research grants in the Arts and Humanities, meanwhile, were subordinated to governmental agendas, pushing the humanities to engage in “useful” areas having very little to do with the humanities proper, including “Global Threats to Security,” “Ageing: Lifelong Health and Well-being,” and “Living with Environmental Change.”19

Under the new coalition—best referred to in this context as “Con-Dem”—this coercion of the arts and humanities is about to become outright liquidation. The government body responsible for the public funding of universities, the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), is cutting 80 percent of its teaching grant for universities and replacing it with income from tuition fees. The remaining 20 percent will be ring-fenced for four priority subject areas, referred to as STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths). In other words, the teaching of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences in universities will no longer receive state funding after 2014–15, forcing these departments to follow a market logic: degrees in these subjects can continue to be issued as long as there are enough students willing to pay high enough fees. This is a significant change in the ethos of education. Instead of giving funding directly to universities to administer as these institutions wish, the government will lend money to students to “invest” in a course (and their own career), which they will pay back, with interest, over the course of 25–30 years, according to each graduate’s level of income.20

There are two main points here: first, an attack on the humanities (and the critical thinking they stand for), and second, the privatization of education, which is no longer considered a democratic right and a channel for social mobility. Before I address these, a little context is necessary. Unlike the US, the UK has had a model of entirely free education since the 1940s. Following the end of World War II: tuition fees were covered by a local authority and were accompanied by a generous “maintenance grant” to support living expenses. Things continued in this vein until 1988, when Thatcher’s Education Reform Act sought to create a “market” in education, with schools and universities competing with each other for customers (pupils/students), universities funded according to their performance, and the abolishment of academic tenure. From a student’s perspective, not a huge amount changed until a decade later, when tuition fees were introduced and a means-tested maintenance grant was replaced by a government loan to be repaid as soon as graduates earn an income of £15,000 or more.

At the moment, tuition fees are capped at £3,224 per student per year. Under the new system, fees will be at least £6,000 per year, with an option of rising to £9,000. (Given the prestige associated with scarcity, it is likely that most universities will raise their fees to the maximum amount.) The government claims that the poorest quarter of students will be better off under the new scheme, paying less per month in repayments—but for a longer amount of time (a mortgage-like life sentence of 25–30 years). There has been a great deal of number-crunching as to whether or not the proposed repayment scheme actually does leave students from low-income backgrounds better off, but it misses the ideological point.21 All students will be saddled with debt of at least £40–50K that will inevitably hit the poor hardest. (Even though the rich will not be allowed to repay their loans in one go, no statement has been made as to whether there will be a penalty if wealthy students do not take out a loan.) For the lowest income students, it will surely reduce the inclination to go to university altogether, despite Cameron’s tokenistic talk of a £150 million subsidy for scholarships for the poorest. (There are currently 750,000 students from lower economic backgrounds in higher education, and the proposed scholarships will only cover the first year of tuition fees.22) Dressed up in a benign rhetoric of egalitarian progressiveness (now everyone can be educated—and in debt!), the blithe snobbery of the government’s position can be sampled by glancing at an article by Michael Gove, now Education Secretary, from 2003: “Anyone put off from attending a good university by fear of that debt doesn’t deserve to be at any university in the first place.”23 The arrogance and privilege of this statement beggars belief. It is utterly obscene that a post-war generation who enjoyed free education as a democratic right can now, while in government (as a result of that free higher education), condemn future generations to a lifetime of liability.

Further assaults on the ability of low-income students to enter university have also been made by axing the Education Maintenance Allowance, a benefit that allows 16–18 year olds to stay in education, rather than feel pressured to go out and earn a living. An independent report by the Universities and College Union (UCU) finds that a number of universities are now at risk of closure—most critically those that teach “non-priority” areas (i.e. the arts and humanities), those without a large number of high fee-paying overseas students, and those that attract students from the poorest backgrounds.24 It’s a Darwinian mentality: universities with a strong track record in STEM, and in the corporate investment it already attracts, will survive, while the specialist arts colleges will fail. And those universities with the most to invest (in facilities, resources, services, the student experience) will be those able to charge the most—and this advantage will replicate itself by propagating an ever-wider gap.

All of which renders the government’s claim for making education more egalitarian and progressive through market choice a patent lie. The idea that students are best placed to decide what they should expect from higher education makes a mockery of the idea of education producing sound judgment in the first place (as Stanley Fish points out, “if students possessed it at the get-go, there would be nothing for courses and programs to do”).25 But such an objection contradicts the government’s most fundamental assumption—that what students want from higher education is value for money, not critical thinking about value itself. Faced with a future debt of up to £50,000 (if one takes into account loans necessary for accommodation and maintenance), there will inevitably be a decline in student enrollment for degrees in the humanities. As Martin McQuillan (Professor of Literary Theory at Kingston University) wryly observes, “The unregulated market being flawless, if all students choose “priority” subjects, then as a matter of dogma it is fine for Art History and Classics to go out of business.”26 Departmental closure is not unheard of: back in the 1980s, when the market principle was first introduced, numerous departments of Chinese, Russian, and Islamic Studies were shut down because there was insufficient demand for them.27 Perhaps more insidious, though, are the underlying class consequences of subjecting the humanities to a free market. Courses that deliver employability will thrive, while those that don’t will disappear—or be propped up by the children of the rich. It’s a policy that can only re-cement rigid class and cultural distinctions: “philosophy for the bourgeoisie; ‘vocational’ courses for the masses.”28

A number of academics, all from the Humanities, have vividly spoken out in public—although none of them have been Vice Chancellors in positions to take a practical stand. Several have used the metaphor of death to describe the withdrawal of support for the humanities, seen as the lifeblood of universities. Alex García Duttman (Professor of Philosophy at Goldsmiths) has argued that a university without humanities

will survive only as a simulacrum of life, a death worse than death, a life of zombies, with students no longer being students but clients and consumers, and with academics no longer being academics but replaceable entities in a service industry designed to satisfy the desires of clients and consumers who pay a high price for such satisfaction. Today, the value of an academic is already measured against his ability to provide money by being successful at getting enormous grants. The model of the academic is the networker and the lobbyist, not the researcher and the teacher.29

Terry Eagleton, former Professor of English at Manchester University, continues in a similar vein:

What we have witnessed in our own time is the death of universities as centres of critique. Since Margaret Thatcher, the role of academia has been to service the status quo, not challenge it in the name of justice, tradition, imagination, human welfare, the free play of the mind or alternative visions of the future. … there is no university without humane inquiry, which means that universities and advanced capitalism are fundamentally incompatible. And the political implications of that run far deeper than the question of student fees.30

Eagleton’s point invites us to consider the urgent question of whether universities can indeed be run like businesses, or whether the academy—and the humanities in particular—is fundamentally inimical to commerce. As Bill Readings has argued, the university was once “linked to the destiny of the nation-state by virtue of its role as producer, protector, and inculcator of an idea of national culture.”31 Under neoliberalism, the university is no longer tied to the production of culture and moral values, but to the profit motive (or what has been called “academic capitalism”).32 The idea that the university might be a place where research cannot always be accounted for, where teaching cannot be reduced to supply and demand, is entirely foreclosed in the Con-Dem cuts. To quote García-Düttman once more, the life of the university “depends on a surplus, on the superfluous and the excessive, on what cannot be measured, calculated, integrated, put to work.”33

The idea of state withdrawal from university funding is so deeply ideological that it barely needs to be stated. It is driven by a belief in the free market as the best way of organizing education, and seeks to curtail the freedom with which it has traditionally governed education and culture. Other European countries dealing with equally huge national deficits have decided to protect funding for universities, severely compromising Cameron’s statement that “We have no choice. We need change… it’s right that when it comes to doing this, successful graduates pay their share.”34 (The language of “there is no other choice” is one of the central rhetorical tenets of neoliberalism—recall Thatcher’s “there is no alternative.”) A language of personal accountability replaces one of social investment; in Tory eyes, only those who go to university should pay for it. (Is it only a matter of time before this logic is applied to hospitals too?) This line of thinking doesn’t even keep with neoliberalism’s ethos of socialized risk and privatized benefit (as was demonstrated so appallingly during the bank bailout), since it now privatizes risk at the individual level of education. As Fish comments, “Higher education is no longer conceived of as a public good—as a good the effects of which permeate society—but is rather a private benefit, and as such it should be supported by those who enjoy the benefit.”35 That the present generation of students, parents, and faculty has taken to the streets to protest against this threat to everyone’s future shows how profoundly this ideological shift in British education is being experienced.

Conclusion

Compared to how the Con-Dem cuts will impact education, cultural funding is in a relatively stable position. But there is a still an underlying narrative tying both together. Culture—like the arts and humanities in education—is seen as an indulgence in “these difficult times” when vital social provisions (hospitals, housing benefit, and so forth) are all being cut back. But the attitude that the arts are a luxury—that they are intrinsically privileged, simply because they can’t be accommodated by a market logic—actually creates and perpetuates this lie: without public subsidies, culture and the humanities are actually transformed from human necessities into luxuries, becoming the preserve of a wealthy few. The fight against cuts to arts and humanities funding is not a question of defending a luxury, but should be seen as part of a broader opposition to the destruction of the welfare state and the whole principle of austerity measures in general, in which the working and lower middle classes have to bear the brunt of the bank bailout to sustain the status quo. The “age of austerity” is only a screen for the further dismantlement all public services in the UK (from the NHS to free education to public funding for the arts), the most civilized of Britain’s accomplishments in the twentieth century. The end of public funding is the end of the public sphere, our most progressive institutions, and their commitment to non-commercial activity as a good in its own right.

It goes without saying that a subordination of cultural activities to market logic leads to the reinstatement of class division and privilege. Future generations of youth who want to improve their chances in life through higher education will not have the freedom of indecision and intellectual exploration available to them, and will instead need to make strategic financial decisions at the age of eighteen that will saddle them with lifelong debt. This is balancing budgets as class offensive, profoundly inimical to a socialized mentality in which everyone’s taxes pay for everyone’s education and society’s gain. Of course, dreaming of an alternative society, in which everyone has access to higher education as a democratic right, is decried by those in power as a lack of realism. In December, the Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg said, “I would feel ashamed if I didn’t deal with the way that the world is, not simply dream of the way the world as I would like it to be.”36 But what a sorry world it is when we can’t even envisage alternative horizons, such as addressing the deficit by other means: pulling out of Iraq and Afghanistan, scrapping Trident, and clamping down on corporate tax evasion, for a start.37

Graduating in 1994, I was part of the last generation to receive a full maintenance grant and tuition fees from the UK government. My parents were in the lowest income bracket; I lived in the middle of nowhere (a small village in Wales), and went to a state school where there was never mention of students applying to university. I studied Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic—in the eyes of the present government surely one of the most futile subjects known to man, offering zero social and economic benefit. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life, but reading sagas and deciphering runes somehow kept my soul alive, as did the switch to Art History, and my eventual ability (only a decade later) to earn a living from this decision. It pains me unspeakably to see that the freedom of an open cultural horizon is no longer available to future generations, who will be piled up with debt from the age of 18, tied into a debtor-speculator model that so benefits neoliberal political elites. All power to the protests, and to spreading the word that there are alternatives: not everything can or should be subject to the rule of the market.

Here I am paraphrasing Michael Billington’s comments in “Acceptable in the 80s,” The Guardian, April 11, 2009. See →.

See Peter Hewitt, “Beyond Boundaries: the arts after the events of 9/11” (speech, National Portrait Gallery, London, March 12, 2002). Hewitt was speaking as Chief Executive of Arts Council England, the government funding agency for the arts.

The creative industries are those that “have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent and which have a potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of intellectual property.” These include music, publishing, films, games, advertising, fashion, design, TV, and radio, all of which have obvious commercial potential. See DCMS, → Creative Industries Mapping Document 2001. 2nd ed. (London: Department of Culture, Media and Sport, 2001) A follow-up document was published in 2003.

DCMS and DfES, All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education (London: DfES, 1999).

DCMS, Culture and Creativity: The Next Ten Years (London: Department of Culture, Media and Sport, 2001). A Green Paper is a government report that forms the first stage in changing a law in the UK.

Angela McRobbie, “‘Everyone is Creative’. Artists as Pioneers of the New Economy?” See →.

In the All Our Futures policy document, the DCMS and the Department for Education and Skills noted that “adult learning will in future take place in a world where flexibility and adaptability are required in the face of new, strange, complex, risky and changing situations; where there are diminishing numbers of precedents and models to follow; where we have to work on the possibilities as we go along…”

McRobbie, ‘“Everyone is Creative.”’

Faisal Abdu’Allah et al, “Tory plans for a culture of cuts,” The Guardian, October 1, 2010. See →.

Alan Davey, cited in Jackie Warren, “One Hundred Arts Organizations Face Destruction From UK Budget Cuts,” World Socialist Web Site, November 29, 2010. See →.

Lyn Gardner, “This Arts Council cut will devastate theatre,” The Guardian, March 30, 2007. →.

DCMS, reported in Dea Birkett, “Museum moments are worth preserving,” The Guardian, November 18, 2010. See →.

For a discussion of the disastrous consequences of reliance on short-term corporate funding, see JJ Charlesworth’s excellent analysis of the Institute of Contemporary Arts. JJ Charlesworth, “Crisis at the ICA: Ekow Eshun’s Experiment in Deinstitutionalisation,” Mute, February 10, 2010. See →.

“Giving to the Arts,” Financial Times, December 12, 2010.

David Cameron, “Big Society Speech” (speech, Liverpool, July 19, 2010). See →.

Cameron, “Big Society Speech.”

The Olympics are absorbing £2.2 billion in National Lottery money over the 2005—2012 period, leaving £322.4 million less for arts and heritage. Farah Nayeri, “Tate, British Museum Plead Against Arts Funding Cuts,” Bloomberg, March 25, 2010. See →. Jeremy Hunt reminds us that “three fifths of Britain’s biggest donors—those giving more than £100 a month—have incomes of less than £26,000 per year.” Jeremy Hunt, “Philanthropy keynote speech” (speech, European Association for Philanthropy & Giving conference, London, December 8, 2010). See →.

From the perspective of recent contemporary art, these imposed social orientations might seem reasonable enough, but for those who work in medieval literature—or indeed, any period for which these themes are not transhistorical absolutes—the opportunities for having your research funded become very bleak.

The idea is that this will recoup money for the government, but numerous reports have pointed out the deficiencies of this model. Current figures are based on equal numbers of male and female graduates earning steady wages that increase by 4.47 percent each year, but there are more female graduates than male, and on average they earn less than men and take time off to have children. The figures also do not take into account those who do not graduate, either by dropping out or failing exams. See John Thompson and Bahram Bekhradnia, “The government’s proposals for higher education funding and student finance—an analysis,” at →. The authors conclude that the new system is as likely to cost public money as it is to save it.

The Institute of Fiscal Studies argues that if the numbers are calculated via graduate earnings, the highest earning graduates would pay more on average than both the current system and that proposed by the coalition, while lower earning graduates would pay back less. But if one takes parental income as the key figure, graduates from the poorest 30 percent of households would pay back less than under the proposed system, but more than under the current system. Haroon Chowdry, Lorraine Dearden, and Gill Wyness, Higher Education Reforms: Progressive but Complicated with an Unwelcome Incentive (London: Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2010), 1. See →.

As the IFS also point out, the National Scholarship Fund also provides a perverse incentive for universities to turn away student applicants from the poorest backgrounds. Chowdry et al, Higher Education Reforms, 1.

Michael Gove, “If I’m paying for your education, so can you,” The Times, January 21, 2003. See →.

University and College Union, Universities at Risk, December 2010.

Stanley Fish, “The Value of Higher Education Made Literal,” New York Times, December 13, 2010. See →.

Martin McQuillan, “The English Intifada and the Humanities Last Stand,” The LGSthoughtpiece, December 11, 2010. See →.

Humanities Defence Petition, at →.

Mark Fisher, “Winter of Discontent 2.0,” k-punk, December 13, 2010. See →.

Alex García-Düttmann, “The Life and Death of the University,” Goldsmiths Fights Back, December 8, 2010. →.

Terry Eagleton, “The Death of Universities,” The Guardian, December 17, 2010. →. For another forceful critique of the cuts, and police behavior at student demos, see the article by Peter Hallward (Professor of Philosophy, Kingston University), “A new strategy is needed for a brutal era,” Times Higher Education, December 13, 2010. →.

Bill Readings, The University in Ruins (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996), 3.

Sheila Slaughter and Larry L. Leslie, Academic Capitalism: Politics, Policies and the Entrepreneurial University (Baltimore and London: John Hopkins University Press, 1997).

Alex García-Düttmann, “The Life and Death of the University.”

David Cameron, “PM’s speech on education” (speech, CentreForum think tank, London, December 8, 2010). See →.

Stanley Fish, “The Value of Higher Education Made Literal.”

Nick Clegg, cited in “Tuition fees: Nick Clegg says opponents of rise are ‘dreamers’”, The Daily Telegraph, December 9, 2010. See →. This is a grim riff on the 1960s version: “Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not.” This line has been attributed to Bobby Kennedy, paraphrasing George Bernard Shaw.

In October 2010, Vodafone were reportedly let off £4.8 billion of tax by HM Revenues and Customs. Businessman Philip Green put the ownership of his UK-based Arcadia empire (which includes Top Shop) into his wife’s name in Monaco and paid her £1.2 billion, tax-free. These are not isolated examples, but the norm. Only 33 of the FTSE 100 companies published a list of where their subsidiary companies are located, even though it is a legal requirement for them to do so. In addition, these companies tax rate will fall from 28 percent to 24 percent in the next four years (while VAT on all products will rise from 17.5 percent to 20 percent). There is a clear discrepancy between the government’s message that we all have to contribute to the austerity measures, and the reality of corporate business. The Vodafone incident triggered a wave of activism by UK Uncut that led to 30 stores being closed nationwide in October 2010, while Top Shop and 22 of Green’s other stores were occupied and temporarily closed down in December 2010.

Category

Subject

Many thanks to Laura Barlow and Mariana Silva for their invaluable research assistance on this article.