When Paul Chan and Sven Lütticken proposed to gather a series of “reports” on the (mostly) recent rise of right-wing, populist movements for e-flux journal, it was immediately apparent that the urgency and complexity of the topic required its own special issue. As protests erupt throughout Europe in opposition to austerity measures being pushed through by right-wing governments and EU fiscal bodies, we are also now witnessing a phenomenon spreading throughout the Northern Hemisphere in which some of the most brazen hardline racist rhetoric emerges not only from politicians, but from the general populace as well. What is going on? It is our pleasure to present Chan and Lütticken’s Idiot Wind: On the Rise of Right-Wing Populism in the US and Europe, and What It Means for Contemporary Art as the January/February 2011 issue of e-flux journal.

—Julieta Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood, Anton Vidokle

The global financial crisis that began in 2008 continues to impoverish countries by exposing them to punishing economic forces that seem neither controllable nor accountable to the sociality from which they spring. And, like clockwork, right-wing populist movements in the US and Europe step onto the social stage to reassert the will of “The People” in these great times.

These populist movements reconceptualize real fears about deteriorating social and economic conditions as an imaginary loss of an “original” commonality at the center of society that must be renewed at the expense of those living at the circumference. Xenophobia, racism, nationalism, and homophobia fill the void left by the loss of lives and livelihoods ungrounded by the downturn. Government austerity measures meant to contain the economic fallout further erode the interconnections between classes, races, and ethnicities that make up contemporary life, adding to the growing sense of social isolation, which in turn reinforces the desire to forge a common country by punishing what is considered most foreign from within.

The profiles and trajectories of the movements differ. In Denmark and Holland, populist parties outside of government are poised to influence legislative policies because those governments depend directly on the parties’ support. In the UK, where the UK Independence Party has had limited national success, David Cameron’s seemingly inclusive “Big Society” populism is now leading the savage dismantlement of the public sector under the auspices of being a “dramatic redistribution of power from elites in Whitehall to the man and woman on the street.” Germany has a tradition of Neo-Nazi parties, but their political potential remains limited. Although public support for Thilo Sarrazin is widely regarded as a sign that a new kind of populist party can gain prominence—and politicians such as Horst Seehofer try to score by echoing his discourse—he remains a media phenomenon for the time being. In general, the policies and rhetoric of politicians in established political parties are increasingly shaped by the rules of the populist game, as in Sarkozy’s campaign against the Roma. Meanwhile, in the US the Republican Party is being transformed from within by the dramatic rise of the Tea Party movement.

And while American libertarianism, which forms the historical core of the Tea Party, favors a weak central government, many of the right-wing movements in Europe favor a comparatively strong state—even while attacking immigrants and “benefit scroungers,” promising that they take a stand for “the hard-working citizen.” Another difference is the role played by Christianity. In the US, the evocation of God is de rigueur in populist organizing and party politics in general, despite the separation of church and state. The situation in Europe is less clear-cut, with some of the most visible and successful right-wing populists being militant secularists. Yet there are transatlantic coalitions. Pamela Geller, the US blogger famous for crusading against the “Ground Zero Mosque” and halal Campbell’s Soup, invited the militantly anti-Islam demagogue Geert Wilders to speak at a 9/11 commemoration. Dutch Islam-bashing has for the most part been militantly secularist, though this has not prevented strange coalitions with Christians, particularly in the US. At the American Enterprise Institute, the Somali-Dutch Ayaan Hirsi Ali is a colleague of Newt Gingrich, who has called for a “re-Christianization” of the US. Ultimately, perhaps it is irrelevant which narrative is being embraced: that of a fight of the Enlightenment and secular democracy against Islam or that of Christianity against Islam. In both cases, history is relentlessly turned into myth.

Populism lays claim to channeling the vox populi; this is its strength against established political orders mired in compromise and careerism. Tea Party favorite Sarah Palin is famous for her public gaffes like “refudiate,” but they only increase her political capital as someone who is “of the people.” And yet, many populists hardly affect a folksy demeanor; the late Dutch populist Pim Fortuyn was a dandy who lived in a villa called “Palazzo di Pietro,” and Thilo Sarrazin in Germany is an establishment figure whose core constituency—as evinced by the audiences at his public appearances—consists of an angry and beleaguered bourgeoisie. However one dresses it, populism is class warfare from above—waged by upper and middle classes, along with a beleaguered white working class, against minorities, immigrants, the poor, and the unemployed. It is telling that populist rage focuses on political and cultural elites, while remaining suspiciously silent on economic and financial elites. In a stagnant economy, the redistribution of wealth from bottom to top comes to function as an alternative to the logic of expansion. Promising to safeguard pensions and tax deductions while bashing welfare and various threats to the nation, populists deflect attention from—or actively collude with—this ongoing redistribution of wealth.

In addition to class warfare, most populisms are based on a return to national and ideological origins, leading to characteristic uses and abuses of culture, and of art in particular. If the recent battle around the removal of David Wojnarowicz’s video from an exhibition in Washington, DC is any indication, art’s main role is that of a convenient target for reactionaries looking to energize their political base. Art is defined as alien to “authentic” culture, since it does not explicitly express and affirm the values that embody the country. In some European countries, art is seen as a heavily subsidized field that steals tax Euros away from “the hard-working citizen,” similar to unemployment benefits and other “left-wing hobbies.” On the other hand, art is implicated in a global speculative economy in which it is one more investment option, and in this respect, it is again vulnerable, coming to function as the concrete manifestation of abstract financial forces that weaken national economic sovereignty; an uncommon luxury lacking in both culture and rootedness. And yes, art is indeed part of the problem—how could it be otherwise? Rather than gloss over the issue, one should affirm and exacerbate art’s problematic status, its essential undecidability, which holds the promise of a more productive politicization of contemporary art above and beyond any projects on “aesthetics and politics” or “art and activism.”

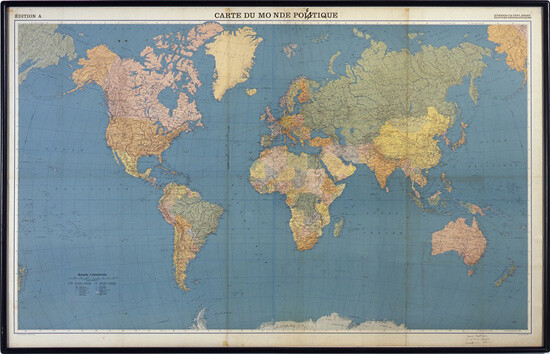

What follows is a selective and subjective map assembled by contemporary artists and writers, a topographic charting of the rise of these right-wing populist movements from a multitude of perspectives and experiences. There are, to be sure, many holes, many empty spots: Switzerland, Italy, Hungary, and Russia, to name a few. This collection does not claim or aim to be exhaustive, as exhausting as it has been to assemble. Working with little time and means, we were forced to rely on existing social and intellectual ties, and on chance. When we invited people in late November to submit “reports” on their neck of the woods, this invitation was obviously a Zumutung—an imposition. In what almost amounts to a parody of the reality of just-in-time cultural and intellectual production, we asked busy people to do yet more work for little pay, and during the holidays. Business as usual, then—or business worse than usual.

Rimbaud reminds us to “change our lots, confound the plagues, starting with time.”1 In an economy marked by an imperative to perform, resistance is increasingly seen in terms of a Bartlebyesque refusal, of a willful passivity. This is not the only way. Preferring not to “get with the program” can also take the form of congregation, of association, of creating constellations that create some space and time to breathe, to be, and to think. We are grateful to the friends and strangers who contributed written reports as well as visual contributions that enter into dialogue with the texts. We edited and talked and argued and thought some more. Time was made.

“Ta tête se detourne: le nouvel amour! Ta tête se retourne: le nouvel amour! ‘Change nos lots, crible les fléaux, à commencer par le temps,’ te chantent ces enfants.” Arthur Rimbaud, Illuminations, and Other Prose Poems, trans. Louise Varèse (New York: New Directions Publishing, 1957), 38.