History Out of Synch

The twentieth century began with futuristic utopias and dreams of unending development and ended with nostalgia and quests for restoration. The twenty-first century cannot seek refuge in either. There is something preposterous in our contemporary moment of postindustrial economic crisis and preindustrial cultural conflict. I see in it not a conflict between modern and anti-modern, or a pure “clash of civilizations,” but rather as a clash of eccentric modernities that are out of synch and out of phase with each other both temporally and spatially. Multiple projects of globalizations and glocalizations overlap but don’t coincide. In this context of conflicting and intertwined pluralities, the prefix “post” becomes itself passé. By the end of the last century various thinkers had mourned or celebrated the “ends” of history and of art, of the book and of humanity as we knew it. While the various “posts” succeeded one another, many premodern myths also claimed their share of the intellectual and spiritual territory.

Instead of fast-changing prefixes—“post,” “anti,” “neo,” “trans,” and “sub”—that suggest an implacable movement forward, against or beyond, and try desperately to be “in,” I propose to go off: “off” as in “off kilter,” “off Broadway,” “off the map,” or “way off,” “off-brand,” “off the wall,” and occasionally “off-color.” “Off modern” is a detour into the unexplored potentials of the modern project. It recovers unforeseen pasts and ventures into the side alleys of modern history at the margins of error of major philosophical, economic, and technological narratives of modernization and progress. Critic and writer Viktor Shklovsky proposes the figure of the knight’s move in chess that follows “the tortured road of the brave,” preferring it to the master-slave dialectics of “dutiful pawns and kings.”1 Oblique, diagonal, and zigzag moves reveal the play of human freedom vis-à-vis political teleologies and ideologies that follow suprahuman laws of the invisible hand of the market or of the march of progress. As we veer off the beaten track of dominant constructions of history, we have to proceed laterally, not literally, and discover the missed opportunities and roads not taken. These lie buried in modern memory like the routes of public transportation in the American landscape traversed by decaying highways and superhighways, surveyed by multitasking traffic controllers.

Off modern is not a lost “ism” from the ruined archive of the avant-garde. Neither is it merely a new brand in the fast-paced market of current artistic derivatives. Off modern is a contemporary worldview that took shape in the “zero” decade of the twenty-first century that allows us to recapture different, often eccentric aspects of earlier modernities, to “brush history against the grain”—to use Walter Benjamin’s expression—in order to understand the preposterous aspects of our present. In other words, off modern is not an “ism” but a prism of vision and a mode of acting and creating in the world that tries to remap the contemporary landscape filled with the ruins of spectacular real estate development and the construction sites of the newly rediscovered national heritage. The off-modern project is still off-brand; it is a performance-in-progress, a rehearsal of possible forms and common places. In this sense off modern is at once con-temporary and off-beat vis-à-vis the present moment. It explores interstices, disjunctures, and gaps in the present in order to co-create the future.

The preposition “off” is a product of linguistic error, popular etymology, and fuzzy logic. It developed from the preposition “of,” with the addition of an extra “f,” an emphatic and humorous onomatopoeic exaggeration. The “off” in “off modern” designates both the belonging to the critical project of modernity and its edgy excess.

In the twenty-first century, modernity is our antiquity. We live with its ruins, which we incorporate into our present, leaving deliberate scars or disguising our age marks with the uplifting cream of oblivion. Off modern, then, is not anti-modern; it is closer, in fact, to the critical and experimental spirit of modernity than to the existing forms of industrial and postindustrial modernization. In other words, it opens into the modernity of “what if,” and not only modernization as it was. It unsettles and embarrasses many political and theoretical narratives that we’ve grown accustomed to.

Cultural Exaptation

The off-modern perspective invites us to rethink the opposition between development and preservation and proposes a nonlinear conception of cultural evolution through trial and error.2 The off-modern artist finds an interesting comrade-in-arms in contemporary science, in particular in Stephen J. Gould’s subversive theory of exaptation that unsettles evolutionary biologists and proponents of intelligent design, techno-visionaries and postmodernists. Exaptation can be seen as a redemption of the eccentric and unforeseen in natural history, a theory that could only have been developed by an imaginative scientist who sometimes thinks like an artist.3

Exaptation is described in biology as an example of “lateral adaptation,” which consists in a cooption of a feature for its present role from some other origin. It happens when a particular trait evolves to serve one particular function, but subsequently comes to serve another. A good example from biology would be bird feathers: originally employed for the regulation of body temperature, they came to be adapted for flight. Exaptations are useful structures by virtue of their having been coopted—that is the ex-apt part of the term: they are apt for what they are for other reasons than their original use; they were not built by natural selection for their current role. Exaptation is not the opposite of adaptation; neither is it merely an accident, a human error or lack of scientific data that would in the end support the concept of adaptation. Exaptation questions the very process of assigning meaning and function in hindsight, the process of assigning the prefix “post” and thus containing a complex phenomenon within the grid of familiar interpretation.4

Exaptations have mostly been studied in terms of biological and technological evolutions. Bizarre as it may sound, our homey microwave ovens started their adventurous life as radar magnetrons. Edison’s phonograph, which evolved into a cinematic apparatus, was born as a recording device for dictation; the internet was introduced as a military communication exchange network. Of course, technological evolution moves much faster than biological evolution does, leaving us many discarded projects and possibilities. A bird’s flight and the unpredictable beauty of a butterfly still amaze us, while Edison’s phonograph and Technicolor film are now part of the twentieth century’s museum of “Jurassic technologies.” (Hopefully the art of cinema is not going to end up on the same museum shelf with the toaster ovens).

Art history as well as the virtual archives of most writers and artists abound in unfulfilled projects of the future anterior. The artistic equivalent of bird’s wings could be found in the silk wings of Vladimir Tatlin’s flying vehicle Letatlin, one of the most famous “failed” projects. Letatlin (in Russian, a play on the verb “letat”—to fly—and Le-Tatlin, the artist’s pseudo-French signature), a cross between the mythical firebird and the prototype of Sputnik with silk wings, was a technical failure: it didn’t fly, not in a literal sense at least, but it enabled many flights of dissident imagination. Its dysfunctional wings became phantom limbs of experimental architecture, art, and technology in the second half of the twentieth century.

Perhaps the best things in life that money cannot buy—like happiness, love, art, and other such useless non-commodities—are examples of exaptation. Yet the off modern is not merely a tautology for any form of aesthetic knowledge or human longing. For the first time in history, exaptation is explicitly reframed, placed at the site of new exploration.

Exaptation is an artistic perspective on evolutionary biology that unsettles scientific determinism yet does not also skew the empirical evidence. Off-modern thinkers and artists sometimes recover experimental paradigms of modernist science abandoned by the scientists themselves. Vladimir Nabokov found non-utilitarian delights in his study of butterflies, but it took the artist in him, not an entomologist, to see them. The strategy of off-modern aesthetic exaptation is particularly apt at bringing together the techne of art and science and can thus produce an alternative form of new media. As Vladimir Nabokov explained: in the fourth dimension of art, alternative geometrical and physical parameters are made probable and thus parallel lines might not meet, not because they cannot, but because they might have other things to do.5 The off modern has a quality of improvisation, of a conjecture that doesn’t distort the facts but explores their echoes, residues, implications, shadows. The off modern is not ashamed of unconventional aesthetic judgment that puts the world off kilter.

Human Error

To err is human, said the Roman proverb, both excusing and celebrating human imperfection. It is not by chance that the off-modern project engages with errands and errors of all kinds. Artists know how slight can be the line between flying and falling, between a failure and a co-creation with human fallibility. These human errors are not mere serendipities, examples of statistical randomness. The off-modern artist plays with the “human error,” making it into a cognitive operation, a new form of passionate thinking. The practice of erring traces the shadow play of evolution and metamorphosis, makes visible the act of change and its nonlinear outlines. It reveals the pentimenti, the compositional exercises, the palimpsests of forgotten knowledge and practice. Erring allows us to touch—ever so tactfully—the exposed nerves of cultural and human potentiality, the maps of possible if often improbable developments.

Erring traces unexpected connections between different forms of knowledge, art, and technology, beyond the prescribed interactivities of specific technological media; makes new flexible cognitive maps based on aesthetic knowledge and ahead of software calculations. This practice is not to be confused with multitasking, which, as recent neurological research shows, can actually dull the brain, substituting surfing for thinking, facility in operating more or less expensive gadgets for original ideas. Making lateral connections requires concentration, creative distraction, gadgetless daydreaming, and longer durations than multitasking would allow.

It is not always possible to make exaptation into a deliberate practice, but one can at least try not to miss the chance when it engages us in some minor dissent, encouraging our defiance of the framed world of omnipresent technological and bureaucratic apparatuses that can be so ingratiating. If we adapt too well—to the market, to the e-world, to the artworld, to political regimes, to the particular institutions we inhabit—we might evolve to the point that the adventure of human freedom would become obsolete. The off modern does not rush to imagine the apocalyptic posthuman future capturing the imagination of frustrated producers of bankrupt TV channels. Artistic exaptation is ultimately a practice of human freedom.

Unlike the new media based on technology alone, the off-modern new media dwells on human error and dances with it. It is driven by the technique of estrangement, a meditation on technology itself, and not by the latest sales pitch for technological gadgets. And for the off-modern nerds there is always a good website, “www.gethuman.com,” which offers useful instructions and phone numbers in the offline world and helps to recover the fuzzy logic of human error.

Edgy Geography

Off-modern perspective affects our understanding of our elective affinities and alternative solidarities through time and space. Off-modern art has both a temporal and a spatial dimension: projects from different corners of the globe can appear belated or peripheral in the familiar centers of modern/postmodern culture. The off modern has been embraced by international artists from India to Argentina, from Hungary to Venezuela, from Turkey to Lithuania, from Canada to Albania. To give a few examples: Raqs Media Collective from New Delhi with their projects on porous time; Guillermo Kuitca with his portable homes and mattress maps; the Hungarian documentary filmmaker Péter Forgács with his “what if” histories and recreated home movies; Anri Sala with his “out-of-synch videos; New York–based artist Rebecca Quaytman with her “lateral moves” towards the forgotten tradition of the East European avant-garde; South African artist William Kentridge with his re-animation of the atonal Soviet opera; experiments in the reinvention of the public sphere through art in the Tirana façade project orchestrated by the artist, Mayor Edi Rama; and experimental public performances using mimes and commedia dell’arte to enforce urban citizenship and the performance of law in Bogota, Colombia, organized by the former mayor of the city, mathematician, philosopher, and unconventional theater director Antanas Mockus. The seemingly peripheral situation of these artists and politicians reveals the eccentricity of the center, and asynchronicity questions the progress of cultural trends and artistic movements that are supposed to succeed one another like well-behaved citizens in the express checkout line. The off modern does not focus on the external pluralism and values of states, with their political PR and imperial ambitions, but on internal pluralities within cultures tracing elective affinities and diasporic intimacies across national borders.

We might be living on the edge of an era when the accepted cultural myths of late capitalism and of technological or digital progress no longer work for us. We are on the cusp of a paradigm shift, and to anticipate it we have to expand our field of vision. The logic of edginess is opposed to that of the seamless appropriation of popular culture, or the synchronicity of computer memory. This is a logic that exposes wounds, cuts, scars, ruins, the afterimage of touch. Its edginess resists incorporation and doesn’t allow for a romance of convenience. Clarification: the off-moderns are edgy, not marginal. They don’t wallow in the self-pity or resentment that comes with marginalization, even when some of this is justified.

So the off-modern edge is not a line in the sand, but a space. Thoreau once wrote that one has to have “broad margins” to one’s life. The off-modern edges are not sites of marginality but those broad margins where one could try to live deliberately, against all odds, in the age of shrinking space and resources and forever accelerating rhythms. To be edgy, then, could also mean avoiding the logic of the cutting edge, even if the temptation is great not to. If you are just off the butcher’s knife on the cutting edge, you will end up devoured before you are examined. The logic of the cutting edge makes you part of the bloody action movie so common in contemporary popular culture, where tears and affect are only computer generated. Edginess requires a longer duration. Only at the risk of being outmoded could one stay con-temporary.

Nostalgic Technologies

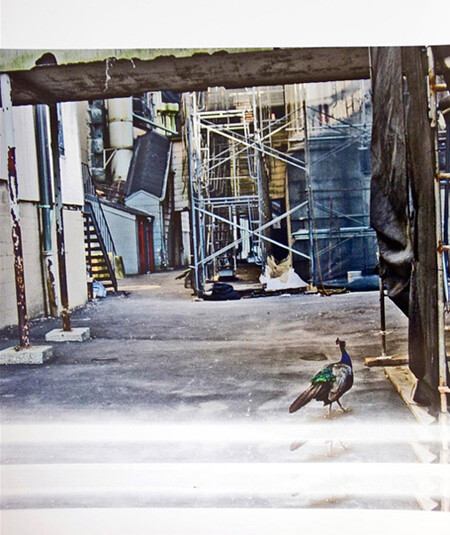

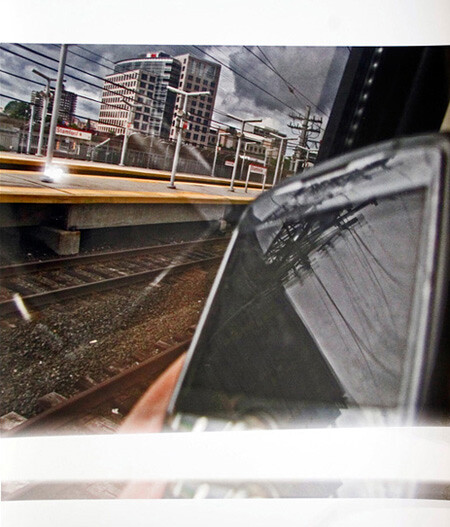

The term “off modern” came to me by accident, as I was dueling with my computer printer, turning it on and off, violating its instructions in the hopes of performing an unpredictable knight’s move in a battle with so-called artificial intelligence. I didn’t have a new black-ink cartridge and wanted to see how my cheap printer would cope with the situation of technical scarcity. It continued working, letting its psychedelic unconscious spill out and yielding a few photographic prints that were unrepeatable and unpredictable. Images without black (without melancholia?) led to a project about nostalgic technologies that involved even more battles with the printer. In a series of “ruined prints” showing our decaying modern landscapes, I pulled the photographs prematurely from the printer, leaving the lines of passages. This error made each print unrepeatable and uniquely imperfect. The process is not Luddite but ludic, not destructive but experimental. An error has an aura.

Erring was also erotic; it teased the technological superego of the digital apparatus, subduing the machine and yielding to it at the same time. Technê, after all, once referred to arts, crafts, and techniques. Both art and technology were imagined as forms of human prosthesis, missing limbs, imaginary or physical extensions of human space.

Many technological inventions, including film and space rockets, were first envisioned in science fiction; imagined by artists and writers, not scientists. The term “virtual reality” was in fact coined by Henri Bergson, not Bill Gates. Originally it referred to the virtual realities of human imagination and consciousness that couldn’t be mimicked by technology. In the early twentieth century the border between art and technology was particularly fertile. Avant-garde artists and critics used the word “technique” to mean an estranging device that lays bare the artistic medium and makes us see the world anew. Later, advertising culture appropriated the avant-garde as one style among many, as an exciting marketable look that domesticates, rather than estranges, the utopia of progress. New Hollywood cinema uses the most advanced technology to create special effects; if artistic technique revealed the mechanisms of consciousness, the technological special effect domesticates illusions and manipulations.

Off modern came to me at the critical edge of artistic practice, or at the aesthetic margin of theory. At the interface between the digital and the material, the metaphorical and the physical. It began as play until distant friends and other artists began to believe in it. The off modern became a con-dition—a state of speaking together.

If in the 1980s artists dreamed of becoming their own curators, and borrowed from the theorists, now the theorists dream of becoming artists. Disappointed with their own disciplinary institutionalization, they immigrate into each other’s territory: the lateral move again. Neither backwards nor forwards, but sideways. An amateur, as Barthes understood it, is one who constantly unlearns the institutional games, unlearns and loves, not possessively, but tenderly, inconstantly, desperately. Grateful for every transient epiphany, an amateur is not greedy.

Black Mirrors

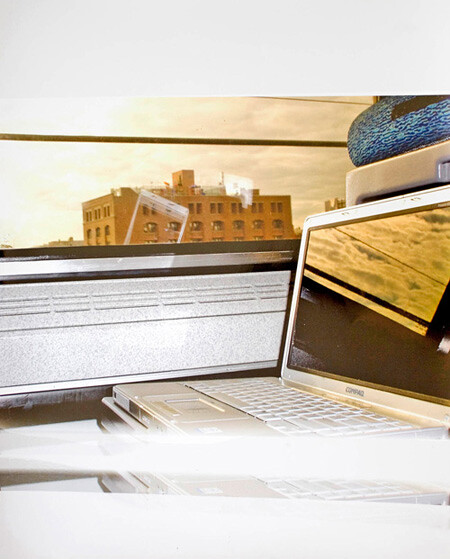

What if we used digital devices improperly and transformed their pixelated interfaces into reflective surfaces and “black mirrors”?

The black mirror—an ancient gadget used by artists, magicians, and scientists from Mexico to India—offers insight into another history of technê that connected art, science, and magic, producing an enchanted technology of wonder. European painters used black mirrors to focus on composition, perspective, and perception itself. When a digital surface becomes a “black mirror” it reflects upon clashing forms of modern and premodern experience that coexist in contemporary culture. In my project The Black Mirror I engaged with pictorial and photographic genres of the past to document a confrontation between modern industrial ruins and virtual utopias. I took a train journey through the American industrial landscape, multitasking with clouds on my digital screens. I used the digital surface as a “black mirror” held up to nature and to the contemporary anxieties on the ground and in the air. The surface of my broken PowerBook looked like a Milky Way spotted with forgotten stars.

This project is techno-errotic—more erratic than erotic, engaged in errand and detour in order to question the new techno-evangelism.

***

The black mirror was an object of cross-cultural fascination, trade, conquest, and sometimes misappropriation. The Aztecs used black mirrors made of obsidian or volcanic glass in divination and healing practices. If a child was suffering from “soul loss,” for example, the healer would look at the reflection of the child’s image in a mirror and examine his shadows. After the discovery of the “New World,” Europeans appropriated the obsidian for anatomic theaters and occult practices, dissecting dead bodies and bringing ghosts back to life. Since the Renaissance, European painters and architects—including Leonardo da Vinci and Claude Lorraine—have used their own black mirrors to focus on composition and perspective in the landscape and to take a respite from color. Sometimes the artists stared into the black mirror to take a break—to catch a breath, so to speak—in order to purify the gaze from the excess of worldly information. The black mirror allowed them to suspend and renew vision.

In the nineteenth century, black mirrors were rescued from oblivion and found their place in the new popular culture of the picturesque. English travelers carried miniature black mirror–like opera glasses, framing and fetishizing fragments of landscape. Absorbed by the possibility of capturing the beauties of the world in the palm of a hand, voyeurs of the picturesque left the world behind. American doctor and spiritualist Paschal Beverly Randolph went beyond the picturesque. Believing in the mystical vitality of the black mirror, he supposedly used opium and his own and his wife’s (and his mistress’) “sexual fluids”—to use Victorian language—to polish its surface.

At the turn of the twentieth century, modern artists from Manet to Matisse resorted to the black mirror, not to reflect an image but to reflect upon sensation itself, on the ups and downs of euphoria and melancholia, or the syncopations of modern creativity. Although the black mirror dims colors, it also sharpens perspective, not framing realistic illusions, but estranging perception itself. The black mirror offers a different kind of mimesis and an uncanny and anti-narcissistic form of self-reflection, in which we spy on our own phantoms in this dim internal film noir.

We no longer live at the end of history, in the time of the forward march of technology or of endless growth. Ours is an off-modern moment, a moment of clashing modernities, industrial and digital. We have become accustomed to accelerated rhythms and the urgent demands of instant, but not intimate, communication. Surrounded by garrulous screens, we barely get a quiet moment for contemplation. The dim realm of personal chiaroscuro has given way to the pixelated brightness of a homepage, bombarded by hits and unembarrassed by total exposure. This new form of overexposed visuality has not been properly documented. When captured on camera, it appears ambivalent, confusing, and barely readable.

I try to catch the digital gadgets unawares, confront them with each other using the alchemy of cross purposes, to put different forms of modern and premodern, technological, existential, and artistic experience in counterpoint. Once upon a time, trains ran on time. These days they rarely do, but now we have a great opportunity to text about it. My train runs through ruins and construction sites of industrial modernity, factories, cemeteries of deceased cars and dismembered bicycles, service buildings that serve no purpose anymore, with graffiti palimpsests on their walls. This landscape is the crisis of the picturesque.

My BlackBerry screen is supposed to be a window onto the fast digital world, not a reflection of the “snail world” of the train running forever behind time. With the BlackBerry off, I get a respite from colorful virtual life. Distracted from “friending” or doing work, I stay in a state of contemplative slumber. I know that nostalgia is not an answer to the speeded-up present, that time is irreversible and shadows will never conspire in the same way again. No longer a seductive digital fruit, my BlackBerry reveals its second life as a melancholic black mirror that puts into sharp focus the decaying non-virtual world that is passing us by.

Viktor Shklovsky, The Knight’s Move, trans. Richard Sheldon (Champaign, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 2005), 4. See also Viktor Shklovsky, “Art as Technique,” in Four Formalist Essays, ed. and trans. Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press: 1965), 3–24. In Russian, “Iskusstvo kak priem,” in O teorii prozy (Moscow: Sovetskii pisatel’, 1983). For a detailed discussion see Svetlana Boym, “Poetics and Politics of Estrangement: Victor Shklovsky and Hannah Arendt,” Poetics Today 26, no. 4 (Winter 2005): 581–611.

Shklovsky observed that artists often borrow and reuse the features of their uncles and aunts and not only of the giant grandparents. Innovation does not mean the invention of a new gadget or even a new language, rather it often follows the oblique moves of mimicry and ruse, and reuse of the features that were considered culturally irrelevant, residual, inartistic or outmoded, placing them into alternative configurations and thus altering the very horizons of interpretation.

Exaptation places eccentric imagination closer to innovation than the brutal struggle for survival of the fittest that extends from Darwin’s theory of evolution to contemporary market capitalism. (It is also a mild consolation to some of us who won’t win in the competition of the fittest but manage to survive thanks to our deviant imagination.)

In fact, the word “evolution” itself is a product of linguistic exaptation and errors of transmission. Originally it meant the unfolding of the manuscript, an opening up of potentialities; the word was not originally favored by the father of the theory of evolution, who only used it a few times at the end of his work, and was adapted by Darwin’s followers.

Vladimir Nabokov, Nikolai Gogol (New York: New Directions, 1961), 145.