To capture death, you need the right technique and the right moment. The public, filmed death of Neda Agha-Soltan had just been sent from Tehran via email, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and every possible television station to the entire networked world when the usual reflex of media critique and propaganda began. Since the photographic image can no longer be trusted, yet no one wants to deprive themselves of it, the roles in this short-lived game are predefined. The anonymously made video, probably shot with a cell phone camera, gave a face to the protests against the results of the Iranian presidential election. The protests became a story that could be retold, fitting for the invention of the “Twitter revolution.”

Due to the news embargo imposed in Tehran, and a lack of other journalistic witnesses, the video simultaneously fulfilled multiple functions of real and symbolic politics. In an initial reaction, the Iranian state media declared the video a fake. At the same time, however, they also confirmed that several people had been killed during the day’s protests. Then, parallel to the blossoming of the Neda cult worldwide, various versions of and conspiracy theories about the death of the young woman began circulating, for example, that British or CIA agents (but no Basij militiamen) had been involved, or that co-conspirators had shot her as a spy while she was staging her own death for the cameras using fake blood. Her striking gaze into the camera was held against her. And while the Iranian cyberwar between state power and the opposition began to grow, thanks to new filtering and anti-censorship programs, the hoax community on the internet also debated all possible details and particularities of the Tehran street scene.

In its emotional logics, the entirely de-contextualized scene recalled another prominent victim icon of recent history: televised images of the death of a Palestinian boy in Gaza shortly after the onset of the Al-Aqsa Intifada. The “France 2” clip from September 30, 2000, shows twelve-year-old Muhammad al-Durrah hanging onto his father for protection as he is hit by Israeli soldiers’ bullets: Palestinians throw stones, Israeli soldiers shoot back, a child dies. In this case, the cameraman was known by name (Talal Abu Rahma), although the correspondent who edited and provided commentary on the film material (Charles Enderlin), was not on site. Numerous streets, squares, and schools in the Arab world were named after Muhammad al-Durrah, the young martyr. The picture of the boy also haunted the macabre video from Pakistan with which the world learned of the beheading of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl in February 2002. In France and Israel, legal and political quarrels, ballistic examinations, and counter-statements culminated in accusations that the filmed scene had been staged by the Palestinians—in the tradition of blood libel legends. Some eccentrics claim that Muhammad al-Durrah is still just as much alive now as he was before.1

Neda, the philosophy student who did not go out to vote, was selected as 2009’s Person of the Year by the London Times. At Queen’s College in Oxford, a scholarship was set up in her name. According to the Times, she was entirely apolitical, but according to her fiancé (a photojournalist appearing in a dubious minor role), she is thought to have said that “each person leaves a footprint in this world.”2 In Farsi, Neda means “voice” or “call.” The anonymous authors of the Tehran video were honored with the George Polk Award, one of the most prestigious journalistic awards in the US, in the newly created category of videography. The award also served to pay tribute to news shows and agencies’ increasing tendency to fall back on user-generated content. Video writes history. Adapting lines from The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, it might be possible to say here that “under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past,” not only do men “make their own history,” but also personally illustrate it.3 NEDA, as an acronym for “Nothing Except Democracy Acceptable,” appeared printed on T-shirts.

But there was one more little surprise: the other Neda. At first glance, her full name, Neda Soltani, could be easily mistaken for that of Neda Soltan. She worked as an English lecturer at the Islamic Azad University, where Neda Agha-Soltan was a student, and was busy with Joseph Conrad at the time. When the video of the dying Neda was sent out to the world and a photo was sought to show her in better days, someone found Neda Soltani’s portrait on her Facebook profile and copied it. Thus, the wrong picture landed in the hands of a hysterical mass media. Television companies throughout the world broadcasted it, newspapers printed it, and it was used in online blogs and articles, sometimes even with the correct name. Mourning ceremonies for the dead Neda were held in front of this photo and angry demonstrators carried it before them as an icon. For the woman depicted, the photo transformed into a memento mori: all of her attempts to weed it from the internet were in vain. She fled from Iran and applied for refugee status in Germany. Even after the parents of Neda Agha-Soltan provided authentic photos, the wrong Neda was still used. Or the wrong name. The online edition of the Guardian from June 22, 2009, had the correct portrait of the deceased Neda under the headline: “How Neda Soltani became the face of Iran’s struggle.” Two weeks later, the BBC posted the mix-up in “The Buzz,” a weekly online inventory chronicling the world of internet forums.4

At issue here is the dictatorship of the fragment and not checking the validity of various individual reports and bits of information. The snuff film’s return as ultimate proof is no good omen. It arrives as a desperate attempt to gain existential meaning from the consumption of images, rather than from the consumption of faith, as in former times. But it is also reminiscent of the old dilemma: what is heard is decisive, not what is said. Perhaps this dilemma (an unsuccessful revolt or coup against contingency?) has replaced the problem of how to represent history.

In July 2008, the photo of an Iranian missile test was published, among other places, on the front pages of papers such as the Los Angeles Times, Financial Times, and Chicago Tribune; and online, on several news sites. It did not take long before the coarse Photoshop manipulation was detected: in the photo, two of the dust clouds had exactly the same shape. The cited source was the website of Sepah News, the propaganda site of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards. But apparently that was also the source for an unaltered photo distributed via Associated Press and Reuters showing three missiles rising diagonally into the sky while the fourth, which misfired, fell. The Washington Post commented ironically: “Iran Apparently in Possession of Photoshop.”5

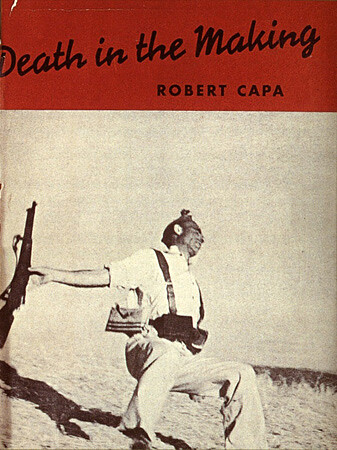

Photography’s melancholy is based on the fact that it shows something that once was and has meanwhile elapsed. By the power of its existence, it confirms that what one sees was actually there; to this extent, it is the epitome of standstill and enchantment. What else is capable of stopping time? “History is hysterical: it is constituted only if we consider it, only if we look at it—and in order to look at it, we must be excluded from it.”6 Barthes referred to the relationship of photography to the tableau vivant, “whose mythic prototype is the princess falling asleep in Sleeping Beauty,” that is, to its reliance on mortifying power.7 In the era before digital image editing, it was not difficult to produce viable proof of the reality of what was depicted—or, if necessary, of the depiction. Should Robert Capa’s Falling Soldier turn out to be a staged photo, not taken in Cerro Muriano in September 1936, but further from the front in Espejo (as has recently been claimed, but not proven), then it would document the reality of a perfectly staged image. Did the photographer use a tripod? Was there a sniper from the Moroccan Regulares who turned a photo shoot into a gory, earnest affair? No other war photo by “Kamikaze Capa” has been subjected to such persistent investigative critique.8 Most likely, critique is aimed more at the fairy-tale moment (kairos) in which the wounded militiaman turns into an angel than at the spectacle of death.

As we know, this snapshot functioned as a symbol for the anti-fascist campaign, as a sign of the demise of the Second Republic in the Spanish Civil War, and ultimately as the “most famous war image.” Capa used it in 1938 on the dust cover for his book Death in the Making, which brought his own photos together with those of Gerda Taro, who had died in El Escorial. Throughout Spain, the quickly buried dead who, in mute opposition to the pacto de silencio, still wait to be exhumed and identified, have not thereby become any less real.

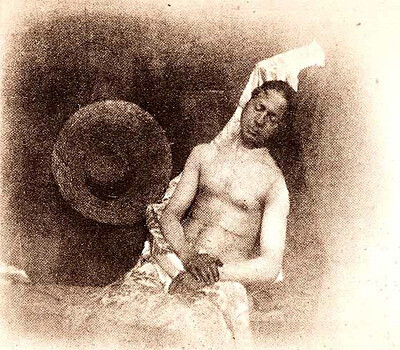

A fake corpse has accompanied the history of photography right from the start. Hippolyte Bayard was independently experimenting with photographic processes at the same time as Daguerre and Fox Talbot. After the Parisian Academy of Sciences refused his application for a patent, in June 1839 he publicly exhibited thirty of his direct positive photographs. It was the first photo exhibition, but Bayard had lost the race for recognition and commercial success won by Daguerre. The following year Bayard produced Autoportrait en noyé, a staging of, and commentary on, the situation: a portrait of the unrecognized inventor as a suicide.

Numerous Parisian Communards who in spring 1871 posed on the barricades for the photographer Bruno Braquehais (a veritable passion, due to the long exposure times) were later identified—from the photos—by Thiers’ police and executed under martial law. It was the founding era of police records and photojournalism. Braquehais was one of the few photographers who had remained in Paris. After the massacres and mass executions during the bloody week in May, which cost a quarter of the working class population their lives, the photographers set out to capture the deserted ruins of Paris. Jules Andrieu photographed the Hôtel de Ville and the palace of justice, the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin, the Tuileries, the arsenal, and Pont d’Argenteuil. He called his series of silver prints Désastres de la guerre. At first glance it is not clear whether the photos are pro or contra Commune—that “sphinx so tantalizing to the bourgeois mind,” as Marx put it.9 And this was clearly not referring to the sphinx from Gustave Doré’s grisaille painting L’Énigme. Ruins are obscure and romantic; they no longer present any danger. When the aesthetic view intersects with the politics of forgetting, ruins no longer even have to serve as portents of doom. The photos show the scorched capital of the nineteenth century as a modern Pompeii (Andrieu had gained relevant experience in Palestine and Egypt). Such photos were treasured souvenirs and stirred the imagination; they inspired London travel agent Thomas Cook to offer all-inclusive tours to the original Parisian sites of action, just a few weeks after the end of the fighting in summer 1871. There, too, business was being done. Henri Dombrowski, a pianist, demanded damages from the photographer Pierre Petit. Petit had falsely presented a portrait of Dombrowski, taken before 1870, as depicting Ladislas Dombrowski, the Commune general mortally wounded in the barricade battles; and had sold 200,000 copies of the photo.

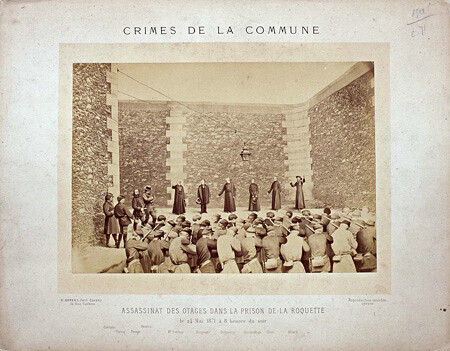

With his Crimes de la Commune, Eugène Appert was the wartime profiteer among the photographers. As “photographe de la magistrature” he compiled photo montages, after the gory defeat, to discredit the Commune. Appert had privileged access to the prisons where he made hundreds of portrait photos; then he staged several spectacular events from recent history for the camera using actors and extras, and inserted the heads of prominent Communards. His theatrical montages of particularly gruesome events were government propaganda and folklore. They are easily recognizable as set-ups. Photos such as Assassinat des otages dans la prison de la Roquette, le 24 mai 1871, à 8 heures du soir (Murder of the hostages in La Roquette prison, May 24, 1871, 8 p.m.) or Massacre des Dominicains d’Arcueil, route d’Italie n° 38, 25 mai 1871, à 4 heures et demie (Massacre of the Arcueil Dominicans, Route d’Italie no. 38, May 25, 1871, 4:30 a.m.) were printed in the popular carte de visite format and served to create a lasting memory of the victors’ version. Appert’s portraits of the prisoners enjoyed great popularity, even among followers of the Commune. Louise Michel carried the photo of her friend Marie Ferré with her for the rest of her life.

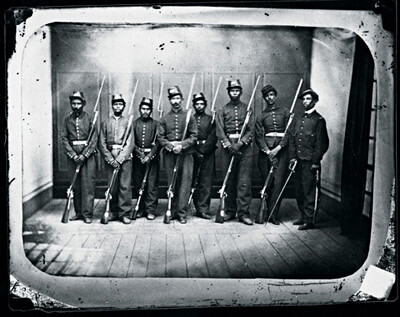

Strictly speaking, the Paris Commune did not have its own photographers. The erroneous belief that the camera—the “eye of history,” in the words of Mathew Brady during the US Civil War—is an objective and democratic medium, lives off of such omissions. Commercialization of Eugène Disdéri’s cartes de visite made photo portraits affordable for the petty bourgeoisie in the Second Empire, but definitely not for the working class.10 During the Commune, workers were photographed either on the barricades or as corpses. Included in the ritual handling of technology was the possibility of depictions being perceived differently according to political views and sympathies. In the perception of Versailles, the exhibited, numbered dead bodies in open coffins were insurgents who had received their just punishment. For the Communards and their supporters, these photos (attributed to Disdéri) documented the unparalleled brutality of repression. The iconography of the Commune’s association with death is no coincidence. One of its decrees (of April 10, 1871) contains the order to systematically photograph unidentified National Guardsmen who had fallen in combat.

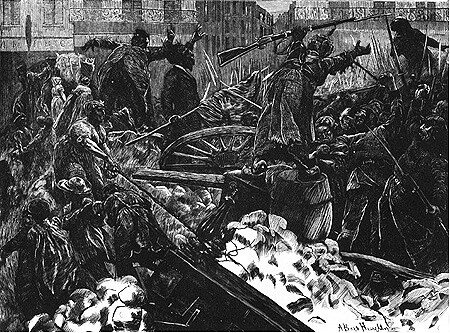

Various reasons can be found for the blind spots in the visual representation of the Commune. A majority of the photographers fled to Versailles with the government, and the situation was similar with many artists. At the start of the Franco-Prussian War, Cézanne, Pissarro, and Monet deserted Paris. Manet and Degas, who had both been members of the National Guard during the German siege, followed after the French surrender. Millet retired to Normandy, old Corot left the city on April 1, 1871. Renoir was not disturbed by the urban revolution; he continued to paint along the Seine. Artists and illustrators involved in the Commune were busy with politics and had no time to make pictures. Instead, there were press illustrators—from England, for example, such as the Pre-Raphaelite-influenced Arthur Boyd Houghton—who came to document the events in Paris for weekly papers such as The Graphic or its competitor, The Illustrated London News.

Most of the photographs that have come down to us were made before or after the Commune, very few during the seventy-two days. Braquehais attended the preparations for the destruction of the Vendôme Column on May 16 and then also photographed the statue of Napoleon lying on the ground. One of the men in the background, festively lining the site of action, resembles the painter Gustave Courbet. His involvement in the Paris Commune is well known, as is the price that he had to pay for it. In June 1870, at the age of fifty, he refused the Grand Cross of the Légion d’honneur. In a letter he wrote, “The State is incompetent in matters of art.”11 Two days after the proclamation of the Third Republic in September 1870 he became president of the art commission and demanded that the Government of National Defense remove the Column—a symbol of the imperial dynasty “void of any artistic value”—from the Place Vendôme. In April, he was elected to the Commune’s Council (which brought him Zola’s ridicule); he became president of the egalitarian Fédération des Artistes and as delegate was responsible for instruction and education. At stake were the artists’ self-organization and the remodeling of hierarchically organized institutions. After the end of the Commune, he was sentenced to six months in prison and a fine. When the new government under Marshal Mac-Mahon confiscated his property and demanded that he personally repay the entire cost of erecting the Vendôme Column again, he feared re-arrest and fled to Switzerland in July 1873.

How much contemporary history is harbored in Courbet’s still lifes and landscapes from his final years? What in them is defensive self-censorship, loss of power, or allegorization of his own matters? Are the countless copies painted by assistants, signed by Courbet, études on the commodity character of art? In Breton’s Nadja, the wonderful light of Courbet’s paintings is the same as that of the Place Vendôme at the moment the Column fell to the ground. On his first trout painting (1872), which he dated 1871 (one year earlier, when he was in prison), he wrote in red next to his name “In vinculis faciebat” (produced in captivity). In this he quoted Jacques-Louis David, who in the tradition of Christian martyr mythology signed his works created in prison after Thermidor 1794 with the same Latin phrase. (Incidentally, Giordano Bruno’s treatise De vinculis in genere also deals with political thinking and the manipulation of reality; Bruno was in fact executed.) The direct depiction of violence is found in only a few sheets in one of Courbet’s sketchbooks, where as an inmate he captures the internment and execution of fédérés. Courbet paints himself in the Sainte-Pélagie prison (thinner and without gray hair), but mainly he paints still lifes: apples, pears, flowers, and lifeless or dying trout. His fish with a hook in its mouth is an image of life’s stubbornness. The apples look like human limbs or miniature bodies; sometimes they seem already a bit rotten.

One of these exile motifs is the Grotte des Géants (a travesty of Courbet’s vulva images?) in the Canton of Valais; another, the Château de Chillon, the castle on Lake Geneva overrun by tourists both then and now. Courbet and Co. (including his assistants Marcel Ordinaire and Cherubino Pata) painted these souvenir images for a solvent tourist clientele, and on commission. Chillon appears in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s novel La Nouvelle Heloïse, one of the most successful books of the eighteenth century; William Turner painted the landscape around Lake Geneva in 1809 on one of his “Grand Tours”; and Victor Hugo and Flaubert visited Switzerland’s most famous castle, which in the past had served as a dungeon for political prisoners. Courbet also certainly knew the narrative poem The Prisoner of Chillon by Lord Byron, who visited Chillon in 1816 with his friend Percy B. Shelley and scratched his own name on a wall. “My very chains and I grew friends,” says Byron’s poem.

What is the meaning of connecting Courbet’s inflationary picture production during his final years to the Vendôme episode and the end of the Paris Commune? The answer that reality has withdrawn from depiction seems too obvious. Is it about not wanting to divulge anything anymore? All images lie when they are not read right. For Marx, the Commune was “a thoroughly expansive political form, while all previous forms of government had been emphatically repressive.”12 The Situationists saw in it the biggest festival of the nineteenth century, the “only implementation of a revolutionary urbanism to date.”13 In Paris, the Impressionists dreamed of their light-flooded gardens, but the specters of the Commune still walked. Parc Monceau, which Monet painted three times beginning in 1876, was full of corpses by the end of that bloody week in May.14 Two or three decades later, when anarchists such as Maximilien Luce painted Neo-Impressionist street scenes from the Commune, it was already too late to let the dead bury their dead. Citizen Courbet had experience and practice in controlling market demand and manufacturing multiple versions of particular motifs. It suffices to recall several of his nudes, hunting scenes, or The Source of the Loue views from the 1860s. In the claustrophobic vulgarity of the Second Empire, they had become vedute of grueling trench warfare: a painter takes revenge using the means available to him. Pictures painted by the ex-Communard who was ostracized in France were highly sought after, from Boston to Vienna. If his realism could be overtaken by political reality, just like any other style, then he might as well have gone ahead and forged his own palette-knife paintings. Genre painting is prosaic. Here, politics is no longer the material that withstands transmutation, as was the case with Courbet’s pictures ca. 1850.15 Looked at in this way, the Commune, too, was no escape. But Courbet’s resignation and mimicry are no less modern than his pornographic materialism in The Origin of the World.

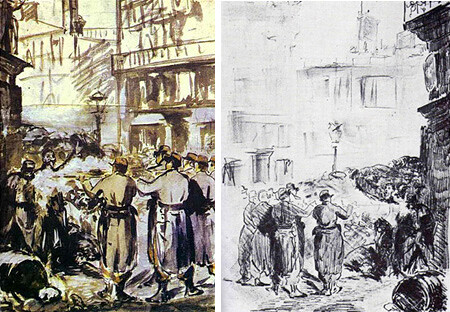

Two lithographs by Édouard Manet refer to the Commune during the “Ordre moral” era. They remained marginal in the atmosphere of brutal state censorship of images, which after the “Semaine sanglante” relied on the politics of major forgetting. Already in 1869, Manet could not show his anti-history painting The Execution of Maximilian (a picture without heroes) in the Salon; his lithography on the same theme was censored. During the “Semaine sanglante,” Manet returned to Paris. Several months later, on November 28, accompanied by two colleagues, battle painter Henri Dupray and illustrator Émile Bayard, he witnessed the execution of three Communards—Rossel, Bourgeois, and Ferré—in Satory. (Shortly thereafter, Eugène Appert’s version of this scene was sold as a carte de visite.) La Barricade (1873) shows a scene in which a Communard is shot by Versailles’ soldiers; Guerre civile (1874) shows a corpse in front of a barricade. The faces are blurry. Both sheets tarry in vague realms, unspecific details, and fall back on previously used motifs. The model for La Barricade was a gouache from 1871. Manet simply took the group of figures with the execution commando from the censured Maximilian sheet, traced it, and transferred it to the litho stone (prints were first made ten years later, posthumously). The civil war corpse lying in front of the barricade clearly recalled the supine torero from the painting L’homme mort (1864–65), which Manet had also made a version of as an etching.

For The Execution of Maximilian, Manet referred to Goya’s painting El tres de Mayo de 1808—as would Capa for the magical snapshot of the mortally wounded Republican militiaman. In 1814, Goya announced to the interim government in Madrid his burning desire “to eternalize the most heroic deeds of our glorious revolt against the tyrant of Europe” in two propaganda paintings.16 He was concerned with correcting his political entanglements during the French occupation. Six years after the pictured events, that was best accomplished through passionate empathy with the victims. Goya had not witnessed the shootings on the Príncipe Pío; The Third of May is a work of imagination.

Nor did Manet have firsthand knowledge of the Cerro de las Campanas in Querétaro, Mexico, where Maximilian I was executed on June 19, 1867, together with his generals Miramón and Mejía. He gathered the information that he needed from the press and from images in circulation, to the extent that they were able to slip through Napoleon III’s censorship. A member of the European aristocracy being sentenced to death by a Republican president of Zapotec origins in a legal proceeding was just as new as it was unsettling. News of the execution of the Habsburg puppet emperor—symbol of the political debacle of French intervention in Mexico—reached Europe by telegraph (the overseas cable had been put into operation in 1866). François Aubert (Maximilian’s favorite photographer) had taken several shots of the execution site, the men in the firing squad, the embalmed corpse, and the emperor’s perforated relic-like shirt. There are no photographs of the shooting itself. However, Aubert made a pencil drawing on location.

Manet signed the final version of his Execution, completed in 1869, with the historical date of the execution. The often-invoked indifference involved in this kind of painting can lead one to assume that here the painter took on the role of photographer or photojournalist.17 But what is Manet’s punctum? It is the glamorous white and gold tones that flit through the entire picture from figure to figure; the ornamental veil of sleepiness that lies over the event; the diffuse shadow on the right in the foreground … or the painted adobe wall, which “is no more than the repetition of the canvas itself.”18

From time to time, style-conscious art historians voice regret that Baudelaire, whose “modernité” was intended as a counter-concept to photography, chose “Monsieur G.,” the illustrator Constantin Guys, for his program of painting modern life instead of Manet. In Baudelaire’s canonical essay, it is said that Monsieur G. provided pictures from the sites of war, for example, the Crimean campaign, as engraver’s drafts for an illustrated weekly paper (The Illustrated London News).19 The first war photographer, Roger Fenton, did not photograph combat operations or dead bodies. In his photos, war is a picnic. James Robertson’s and Felice Beato’s photos show the ruins of Sevastopol; as Mark Twain remarked, the devastated Pompeii looked good by comparison. Beato was probably also the first to photograph dead bodies in a war: the remains of Indian resistance fighters in Lucknow after the crushing of the Sepoy revolt in 1858. Shortly thereafter, the iconography of the American Civil War delivered exhaustive proof that photographers roam the world as agents of death. Artists as war reporters (during the Civil War for Harper’s Weekly or Leslie’s Illustrated News) were a dying breed, but until the spread of half-tone printing, their drawings continued to be used as up-to-date illustrations.

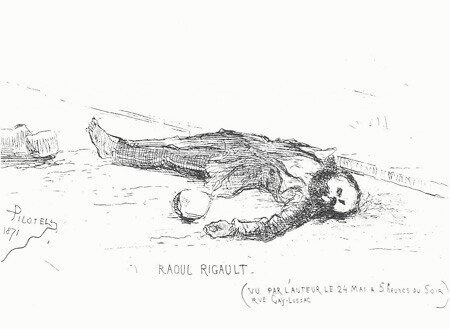

Under the title Avant, pendant et après la Commune and in an edition of only fifty copies, a portfolio appeared in London in 1879 with twenty-one etchings by Georges Pilotell, “ex-directeur de Beaux-Arts” and “ex-commissaire spécial” of the Commune, even briefly a rival of Courbet. During the bloody defeat, Pilotell fled from Paris. A military court condemned him to death in absentia. He was a survivor, a living dead who in exile wanted to keep his memories of the “République universelle” alive. “La Révolution est une souveraine,” says an April poem in Victor Hugo’s L’Année terrible. Liberty was a woman, at least in the dreams of men. Most of the sheets were created between 1870 and 1873, first in Paris for Pilotell’s own magazine, La Caricature politique, then in Geneva and Milan. In London he worked over his drawings and exhibited them in 1875 at the Royal Academy. Sketch artists like Monsieur P. had to be fast: at the National Gallery, he portrayed the art critic John Ruskin looking at Turner’s Apollo Killing the Python. Later, Pilotell worked as a fashion designer, for example, for Debenham & Freebody. In an etching based on a hastily created sketch, one sees the desecrated dead body of the Communard Raoul Rigault lying in the gutter, with the inscription: “Seen by the author on May 24, 1871, at 5 p.m. on Rue Gay-Lussac.” Photography had not yet monopolized the aura of authenticity. At this very moment, the draftsman was the eye of history.

See the comment by Gideon Levy, “Mohammed al-Dura lives on,” Haaretz, October 7, 2007, →.

Martin Fletcher, “Iranian student protester Neda Soltan is Times Person of the Year,” The Sunday Times, December 26, 2009, →.

Karl Marx, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,” in Karl Marx, Surveys from Exile: Political Writings, vol. 2, ed. David Fernbach (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973), 146.

See David Schraven, “Das zweite Leben der Neda Soltani,” Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin, no. 5 (February 5, 2010): 26–30; Siobhan Courtney, “Neda: A Case of Mistaken Identity,” BBC News (July 3, 2009), →.

Al Kamen, “Iran Apparently in Possession of Photoshop,” The Washington Post (July 11, 2008), →.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 65.

Ibid., 91.

Recently, the media-effective debate of the Capa photo has been based mainly on the investigations of José Manuel Susperregui in his Sombras de la fotografía: Los enigmas desvelados de Nicolasa Ugartemendia, Muerte de un miliciano, La aldea española, El Lute (Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco, 2009).

Karl Marx, “The Civil War in France,” in Karl Marx, The First International and After: Political Writings, vol. 3, ed. David Fernbach (Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 1992), 206.

Gen Doy, “The Camera Against the Paris Commune,” in Illuminations: Women Writing on Photography from the 1850s to the Present, ed. Liz Heron and Val Williams (London: I. B. Tauris, 1996), 30.

Courbet to Maurice Richard, June 23, 1870, quoted in Linda Nochlin, “Courbet, the Commune, and the Visual Arts,” in Linda Nochlin, Courbet (London: Thames and Hudson, 2007), 87.

Marx, “The Civil War in France,” 212.

The fourteen “Theses on the Paris Commune” were signed by Guy Debord, Attila Kotányi, and Raoul Vaneigem on March 18, 1962. Quoted in Situationist International Anthology, ed. Ken Knabb (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 398–401. A more epic version was undertaken by Henri Lefebvre, La Proclamation de la Commune, 26 mars 1871 (Paris: Gallimard, 1965).

See, for example, Bertrand Tillier, La Commune de Paris, révolution sans images? Politique et représentations dans la France républicaine (1871–1914) (Seyssel: Éditions Champ Vallon, 2004), 373.

See T. J. Clark, Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999), 21.

Quoted in Janis Tomlinson, Francisco Goya y Lucientes 1746–1828 (London: Phaidon Press, 1994), 94.

“Indifference to the subject” or even “supreme indifference” was a central concept in Bataille’s 1955 essay. See Georges Bataille, Manet, trans. Austryn Wainhouse and James Emmons (New York: Rizzoli, 1983), 73.

Michel Foucault, Manet and the Object of Painting, trans. Matthew Barr (London: Tate, 2009), 38. The text is the transcription of a lecture delivered on May 20, 1971, in Tunis.

Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, ed. and trans. Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon Press, 1995), 18–21.