Right now I feel that I’ve got my feet on the ground as far as my head is concerned.

—Baseball pitcher Bo Belinsky

1. The great cities in our day are full of people who do not like it there1 [Enter a Letter]

My roommates and I received a letter in the mail the other day. It was addressed to “The owners of: [address of our building].” I opened it and it said:

Real estate urgently needed!

Dear Owner,

Are you considering selling your house? Please let us know. Together with our partner, PlanetHome, we are urgently looking for houses, apartments, and properties, private and commercial.

Kind regards,

UniCredit Bank AG

P.S. If you know of somebody and your reference leads to a successful sale through PlanetHome, we will give you 500 Euros!

I assume that every household in our neighborhood, Berlin’s east Kreuzberg, received a similar letter, written with the assumption that it would happen upon some actual owners and not just humble tenants like us. We had recently heard about an increasing conversion of communal or tenant-occupied buildings into condominiums, as part of the intensified buying-up of Berlin by global investment banks.2 As a city in financial trouble, Berlin makes for a nice buy. We also understand that this is as much part of a local situation shaped by Berlin’s recent past as it is related to larger global developments. But things you are told in a letter feel different somehow.

Sitting in the kitchen with my roommates, studying this hard evidence of the acquisitions battle taking place around us, we are unsure as to whether we should feel worried or simply frame the letter and hang it on our wall as a piece of PlanetHome satire. I inevitably wonder how people in Greece must feel these days, when German politicians openly propose that they sell the Acropolis and a couple of their islands to pay back their debt. When it comes to debt, we all have to share the responsibility, have-nots and property owners alike.

The absurd suggestion to sell the Acropolis helps to remind us of how grotesque the notion of ownership actually is, especially when it comes to places and locations. The temple of our most priceless emblem of democracy is up for grabs—Etwas wird Sichtbar (Something Becomes Apparent), as Harun Farocki beautifully titled his 1981 film. The sword of Damocles over the Acropolis and over our household also reminds us that all that is supposedly owned can also be sold, and that we are just the tenants. We, sitting in the kitchen of “our” flat in Kreuzberg, are tenants in a city that was continuously plundered after the fall of the Wall, first under the auspices of the Treuhandanstalt, and later by the Berliner Bankgesellschaft.3 Berlin is a city that shifted its inevitable crisis onto the heads of its inhabitants, and is now referred to as “poor but sexy,” a slogan coined by mayor Klaus Wowereit in 2003.4

So here we have it: a bunch of tenants in Berlin who have retreated to their kitchen and online communities because their city has been hijacked by hordes of tourists desperately seeking the poor and sexy “capital of creativity.” Staying mostly in their hideouts, the locals’ interactions with what is happening on the ground consist mainly of sneaking out on special trips to a nearby Lidl supermarket or to conspiratorial meetings at friends’ homes. These locals are disillusioned by much of what has happened to this city in recent years, and still struggle with the extent to which, as culturally active individuals of various kinds, they have been (made into) part of the problem. From their online communities they hear of similar issues in other places. A manifesto from a loose alliance of music, DJ, art, theater, and film people in Hamburg announces “Not in our Name—Marke Hamburg!”5 Marke (brand) refers to the attempts by local municipalities and investors to market Hamburg as a “creative city.” “Cities without gays and rock bands are losing the race for economic development,” explains the manifesto:

There could not be a more unequivocal definition of the role that “creativity” is supposed to play: namely of profit centre for the “growing city.”

And this is where we draw the line. We don’t want any of the district developers’ strategically placed “creative real estate” or “creative yards.” We come from squatted houses, stuffy rehearsal rooms, we started clubs in damp cellars and in empty department stores. Our studios were in abandoned administrative buildings and we preferred un-renovated over renovated buildings because the rent was cheaper. In this city, we have always been on the lookout for places that had temporarily fallen off the market—because we could be freer there, more autonomous, more independent. And we don’t want to increase their value now. We don’t want to discuss “how we want to live” in urban development workshops. As far as we are concerned, everything we do in this city has to do with open spaces, alternative ideas, utopias, with undermining the logic of exploitation and location.

We say: A city is not a brand. A city is not a corporation. A city is a community. We ask the social question which, in cities today, is also about a battle for territory. This is about taking over and defending places that make life worth living in this city, which don’t belong to the target group of the “growing city.” We claim our right to the city—together with all the residents of Hamburg who refuse to be a location factor.6

The tenants in Berlin are encouraged by the manifesto. It seems that there are people out there who are once again up for a battle to regain territory, and they ask: what and where are the common grounds today?

2. So get away to Mahagonny, the gold town situated on the shores of consolation far from the rush of the world [Enter the Land]

Jimmie Durham’s work Building a Nation refers to the privatization and subsequent selling-off of communal land in the US, often so that mining companies can harvest the natural resources located under Indian reservations. During a recent conversation between the artist and Michael Taussig at the House of World Cultures in Berlin, somebody from the audience commented that she was struck by the fact that visitors had to walk on Durham’s work7. She asked him about his intention behind engaging the ground in the piece. In his answer, Durham expressed how ridiculous the very idea of ownership of land is to the Indian. He joked about people putting up fences and declaring a piece of land their own. What a stupid idea, he laughed. He described how, while ownership seems to matter a great deal, little attention is given to the actual ground. The notion of the ground, the land, seems to remain abstract for most people. People live in cities far away from the land. Land has no use for them, no purpose beyond recreation and fun trips to “nature.” You go out to nature to use it for things like whitewater rafting. You wear special gear that you buy from special outdoor shops in the city. He went on poking fun at whitewater rafting for quite some time before eventually returning to the question from the audience, explaining that he wanted to reactivate the ground. He wanted to make people pay attention to what they were walking on.

The ground, the land—what an anachronistic idea in a time when everybody seems busy chatting on Skype, acquiring network friends, and debating over intellectual property. Perhaps this is because people think that the battles over the actual ground are long lost, the territories already portioned and sold off. What difference does it make if the land we dwell on is sold by one owner to another? And, for that matter, what difference does it make who owns the Acropolis?

3. Here in Mahagonny, life is lovely [Enter Volkseigentum, the squatter, and a water cannon]

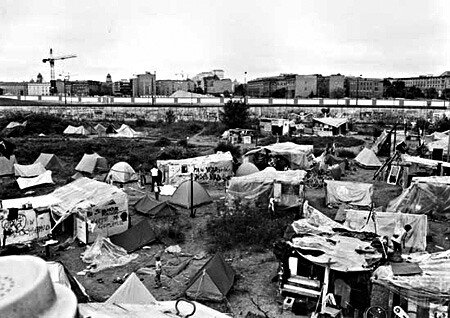

In 1988 the Lennè-Dreieck (Lennè triangle), a piece of land on Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz, located on the west side of the wall, was squatted by a group of a few hundred people. In the course of the occupation the area was renamed “Kubat-Dreieck” after Norbert Kubat, who had died in police custody on May 1, 1987.8 Since 1938 the area had belonged to Berlin’s Mitte district, but when Berlin was partitioned into East and West, it fell into an administrative void. It was physically located on the west side of the Wall, while judicially and administratively falling under the part of Mitte belonging to East Berlin, which meant that the West German police were not allowed to enter the area to evict the squatters. Over a few months people built a village on the land, with huts, communal kitchens, and gardens. When the land was eventually handed over to the West in a barter transaction, the police could finally raid the village. When the inhabitants of Kubat-Dreieck began to climb over the Wall to escape the police, the East German border troops, who were apparently prepared for this illegal border crossing, helped the escaping two hundred squatters over the 3.6 meter-high concrete wall, loaded them into vans, briefly interviewed them over breakfast, and dropped them off at another checkpoint. The West German police seized and sealed off the land after the squatters had escaped, and today the area is owned by Otto Beisheim—a prominent businessman and former member of Adolf Hitler’s personal bodyguard regiment, the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (LSSAH)—who built the Beisheim Center on it in 2004.

This incident could be seen as a forerunner to the peculiar circumstances that surrounded unsettled buildings and land ownership after the fall of the Wall, and the various, divergent ways it was dealt with. In the GDR a great deal of land and real estate, including around 98 percent of industrial facilities, was Volkseigentum—literally “public property,” understood more specifically as a socialist form of public ownership distinct not only from private property, but from state ownership as well, and mainly accumulated through dispossession.

After the fall of the Wall, it became unclear what would happen to this public property. In February 1990 the activist group Demokratie Jetzt (Democracy Now) initiated the founding of a fiduciary organization called Treuhandanstalt, which set out to protect the rights of GDR citizens with regard to the Volkseigentum. In the course of Germany’s reunification the same year, the 8,500 publicly owned enterprises as well as other publicly owned real estate and land—including agricultural land and forests, but also the property of the Stasi, the army, and political parties—were handed over to the Treuhandanstalt by mandate. However, under the legislature of the now reunified Germany, its new objective was to work as quickly as possible to privatize and redistribute the public property of the former GDR according to the terms of the market economy. The German Federal government staffed Treuhand’s board with experienced, exclusively West German managers, and stated that due to the unprecedented scale of the undertaking, the board was to be exempt from any negligence liability. A privatization and restructuring of vast proportions took its course, which was mostly a matter of incorporating East German production facilities into West German companies, followed by the subsequent closing of many of those facilities (partly in order to eliminate competitors).

A few months before the Treuhand was founded, and very close to its headquarters in the former Nazi Air Ministry, a group of people squatted the former WMF (Württembergische Metallwarenfabrik) building. It was one of many squats in the former East German capital. The ambiguous ownership and apparent absence of law enforcement had led to a renewed squatting movement that had previously been strong in the West Berlin of the 1970s and ‘80s. Botschaft, the group that squatted the WMF building, worked collectively and between disciplines to provide a platform for activism and cultural practice outside the frameworks of traditional formats such as art, film, or politics.9 Botschaft’s first large public event was a weeklong series of performances, discussions, and presentations of various kinds addressing the privatization of Potsdamer Platz, city planning, and public space in the age of “Dromomania,” which was the title of the event. “Dromomania” took place just a few days after the police brutally evicted the inhabitants of several squats in the Friedrichshain district using 3,000 Federal Police (the Bundespolizei, or BPOL) and special forces (the Spezialeinsatzkommandos, or SEK), ten armored water-cannon trucks, helicopters, tear gas, stun grenades, and actual live ammunition. Among these squats were the houses of Mainzer Strasse, comprised of twelve units inhabited by a diverse community including a women’s center, a queer squat called “Tuntenhaus,” a community kitchen, a bookstore, and much more.10 As opposed to other squats, the inhabitants of Mainzer Strasse had decided to follow a non-negotiation policy with regard to the police and the municipality. The division between the squats opting for and those opting against negotiation had already led to tensions in the squatter assembly, and the fissure was by now a fait accompli.

“Dromomania” was shaped by these events as much as by the activities around Treuhand and friends. In a moment between the past and the future, a variety of possible worlds seemed feasible, and there was no doubt that one had to get involved. However, there were various opinions as to just how long such a moment should last and what measures should be taken. Whereas some insisted upon the wish that the moment would last forever, others fought to establish more sustainable models of collective ownership and communally run spaces. The moment in fact contained a multiplicity of truths—the truths of the commons as much as the truths of capitalism.

4. But even in Mahagonny there are moments of nausea, helplessness, and despair [Enter Zwischennutzer—and art]

Zwischennutzer sings:

Show me the way

To the next whiskey bar

Oh, don’t ask why

Oh, don’t ask why

For, if we don’t find the next whiskey bar,

I tell you we must die.

I tell you, I tell you,

I tell you we must die.11

In 1991 Botschaft moved from the squat in Leipziger Strasse into a building around the corner. The same year the president of Treuhandanstalt was assassinated by the Red Army Faction. The situation became more complicated.

After the fall of the Wall a huge number of temporary bars, clubs, exhibition spaces, theater venues, and restaurants emerged alongside the squats, none of which had legal licenses. Some of them were part of the squatting movement, but others had special contracts, called “Zwischennutzungsvereinbarung”—a concept that seemed relatively innocent at the time, but has since become a notorious tool of urban development and gentrification. The Zwischennutzungsvereinbarung (literally “interim agreement”) was a temporary agreement between public administrations responsible for legally overseeing a lot of empty real estate, and potential users. The contract included no rent, only running costs such as water and heating, and was terminated when the owner of the building could be determined and/or the owner filed a claim on the space.

In practice, the nature of these contracts was somewhat informal and spontaneous. One would just go to the housing association in Mitte and talk to Jutta Weitz, one of the employees there, and explain what one envisioned doing and what kind of space would probably be required for it. A few spaces would be discussed, sometimes keys handed over, and eventually a contract would be signed with a one-month notice. It was solely through the initiative of Jutta Weitz, who interpreted her job in her own way and wanted to make space for the various dreams and life plans of people, that people’s often quite vague proposals were facilitated. Many activities that shaped the cultural scene in Berlin in the 1990s would probably not have taken shape without her. Her motivation was genuine, her ways radically unbureaucratic, and her attitude socialist. She knew the time and she did everything in her limited power to turn idle property into an anarchic version of Volkseigentum. Knowing the time in this case means “keeping good time,” a phrase Avery Gordon uses in her reflections on knowledge, power, and people:

Keeping good time is about knowing how to tell the time, even if you don’t own a real watch, and simultaneously about knowing whose time it is. In a phrase, keeping good time is about taking sides.12

The complications that accompany the beauty of an ephemeral moment, efforts to make more permanent claims on common territory, and the dynamics of capitalist interests that slowly (or not so slowly) establish themselves in such Eldorados of untapped markets, are painfully epic. Keeping good time seems difficult when any approach is co-opted in the end. What, in effect, are the sides? And whose time is it?

Botschaft, of which I was a member, struggled to tell the time in the midst of this free-for-all. In endless group meetings, attempts at co-option were detected and repelled. An inevitably reactive focus entered the discussions, in part a symptom of an emerging art market in Berlin and increasing international interest in activities taking place there. An indicator of this development was the increasing number of commercial galleries and visitations by curators, players that we were unfamiliar with and very suspicious of. Why should we collaborate with any of them when we could have an exhibition or make a film any time we wanted? It seemed a very silly idea that you would need a curator for such things.

In the meantime, the uncontrolled and unchanneled activities in this temporary autonomous zone of Zwischennutzung and squatting had attracted not only art people. Rich folk from around the world arrived in expensive cars and made their way through the dirt and rubble to the various illegal fun parks and had a ball. Parties are dark zones outside of time, absorbing bodies into their rhythm, momentarily suspending power relations, contradictions, differences. In the daylight, however, bodies return to being carriers of agendas, translating their desires into very different modes of action. While some would sleep until the next party, the people you were dancing with last night might be out buying the very building where the party took place.

The suspension of time found in the party and the logic of the Zwischennutzung contracts seemed to be the perfect expression of the void that Berlin found itself in at that moment—a void of definition, institution, government, industry, and control, an amazing situation that shaped people’s thinking and the landscape of the city. In this sense, the party was a political experience as much as it served the ones who just saw it as a self-service shop. By “political experience,” I mean the challenging and empowering experience of the commons, the creative commons that one shares by working in a collective, and in sharing use of common spaces—an experience that shaped me and probably many others for life. By “self-service shop,” I mean the whitewater rafting mentality on the one hand, and the utilization of the void, the selling of the party for personal or corporate assets, on the other.

As the activities induced by the Zwischennutzung changed into a form of whitewater rafting, events such as “37 Räume” were early and very successful attempts at capitalizing on that mentality. “37 Räume” was an art exhibition in 1992 that invited the international art crowd to trample through the morbidly authentic atmosphere of tiny apartments in the Spandauer Vorstadt, a “jump-start into the international art scene” as its curator Klaus Biesenbach put it.13 Following that, the curator—by then director of Kunst-Werke—presented “Club Berlin” at the Venice Biennale in 1995, and a year later founded the Berlin Biennale together with real estate agent and construction magnate Eberhard Mayntz (who then became vice-chairman of the executive board of directors of Kunst-Werke e.V. and member of the Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art advisory board).14 All of these projects followed the same logic as “37 Räume.”

After Zwischennutzung was discovered by real estate developers and their buddies in the municipalities to be a successful tool for managing urban development and gentrification, it entered the realm of asset accumulation. From its inception, the Berlin Biennale was clearly a collaborative effort between local initiatives seeking to promote Berlin as the future capital of the creative class, and an international crowd eager to throw their seeds onto this seemingly virgin land. But this virgin land was in fact a habitat to many species, the kind of species found on what are called wastelands, uncultivated lands. So the international art “community” came to do their version of whitewater rafting on these lands before their developer friends began bulldozing, partitioning, and selling it off.

5. The men of Mahagonny are heard replying to God’s inquiries as to the cause of their sinful life [Exit, exit, exit, re-enter tenants]

While still sitting in the kitchen, my roommates and I receive an email announcement for a video screening at Basso.15 They are showing films about the eviction of Mainzer Strasse twenty years ago. The email announcement reads:

While the galleries open up the town for a dogfight on “their” weekend and thus push forward another stage in the consumerization of art, and the Biennale decides to place objects of real estate speculation in Kreuzberg—a scandalous decision which hopefully will not be without (fiery) consequences—we turn our eyes back to another time when it was not yet so clear what changes were to come in Berlin.

In the year 1990, before the so-called reunification of Germanies, Western leftists squatted empty buildings in the East, as well as thirteen buildings in what was to become the legendary Mainzer Straße in Friedrichshain. For the twentieth anniversary of the squattings, Katrin Rothe shows her just-completed MYTHOS MAINZER STRAßE - RESEARCH 1, followed by the great classic THE BATTLE OF TUNTENHAUS, Juliet Bashore’s documentary on the Tuntenhaus (house of [drag] queens), also in the Mainzer Strasse.16

This is the first we hear of the Biennale’s new locations. We check their website and, to our dismay, find the majority of its new venues to be in close proximity to our house. Why don’t they just stay in Mitte, the quarter that has already been through every stage of gentrification, already a willing servant to the needs of art mutants, ransacking hordes of budget-airline customers, and other extraterrestrial life forms? We sit in the kitchen and fantasize about the (fiery) consequences this should have. One can imagine that our fantasies are quite raw and juicy, which is often the case when one feels powerless.

For some time now, art has been turning to other domains, to territories and locations unconsecrated by the art canon. These foreign domains seem to be closer to life, more authentic, easier to access, and far more interesting. One of the expressions of this shift has been the claim to site specificity, which also expresses a desire to expand the role of art in society by escaping the ivory tower by way of the public sphere.

Tenant sings:

The liberal arts … being all my study,

The government I cast upon my brother,

And to my state grew stranger, being transported

And rapt in secret studies.17

But site specificity does not create agency by default. On the contrary, it might become a fig leaf for promoting locations, but also a means for self-deceiving traveling artists to think that we can actually really refer to a place by spending some days there and doing a bit of “research.” It is a problem I increasingly encounter in my own work.

So what do we learn from this intricate affair?

6. Lovely Mahagonny crumbles to nothing before your eyes [Enter the Diggers and re-enter]

In October 2008, I suggested to Avery Gordon that we have a conversation in Whole Foods for my Night School seminar at the New Museum in New York. Whole Foods is the largest organic supermarket chain in the US, and Avery and I met at one located just around the corner from the New Museum. The New Museum and Whole Foods both raise a number of questions about the contradictions that come into play when grass-roots movements turn into major corporations. But these contradictions seemed somehow easier to access from within Whole Foods.

While the corporation imitates all the gestures of political agency, it turns them into slogans for a “consumerism without shame.” Clearly, looking at signs that say “power to the people” while purchasing something to eat can actually turn you into a walking zombie. But even in this environment of the undead, the store still appears to be haunted by the struggles that initiated what is now a very profitable enterprise. Perhaps there are ways to reclaim a “life beyond utility,” which is, according to Bataille, “the domain of sovereignty.”18

A key moment in our conversation came when Avery read the Diggers’ declaration of 1649 in the lunch section of the store. The declaration had the heading, “A Declaration from the poor oppressed People of England directed to all that call themselves, or are called Lords of Manors, through this Nation; that have begun to cut, or that through fear and covetousness, do intend to cut down the Woods and Trees that grow upon the Commons and Waste Land”:

We whose names are subscribed, do in the name of all the poor oppressed people in England, declare unto you that call your selves lords of Manors, and Lords of the Land … That the Earth was not made purposefully for you, to be Lords of it, and we to be your Slaves, Servants, and Beggers; but it was made to be a common Livelihood to all, without respect of persons: And that your buying and selling of Land and the Fruits of it, one to another is The cursed thing, and was brought in by War; which hath, and still does establish murder and theft, In the hands of some branches of Mankinde over others, which is the greatest outward burden and unrighteous power … For the power of inclosing land, [privatizing public or common land] and owning Propriety, was brought into the Creation by your Ancestors by the Sword; which first did murther their fellow Creatures, Men, and after plunder or steal away their Land, and left this Land successively to you, their children. And therefore though you did not kill or theeve [although they did!] yet you hold that cursed thing in your hand by the power of the Sword; and so you justifie the wicked deeds of your Fathers; and that sin of your Fathers should be visited upon the Head of you, and your Children, to the third and fourth Generation and longer too, till your bloody and theeving power be rooted out of the Land … And to prevent your scrupulous Objections, know this, That we Must neither buy nor sell; Money must not any longer … be the great god, that hedges in some, and hedges out others; for Money is but part of the Earth; And surely, the Righteous Creator … did never ordain That unless some of Mankinde, do not bring that Mineral (Silver and Gold) into their hands, to others of their own kinde, that they should neither be fed, nor clothed; no surely, For this was the project of Tyrant-flesh (which Land-lords are branches of) to set his Image upon Money. And they make this unrighteous Law that none should buy or sell, eat or be clothed, or have any comfortable Livelihood … unless they bring this Image stamped upon Gold or Silver onto their hands.19

As Avery read from the declaration, it seemed as if we were invisible to all the other people in the store, as if we were acting out the apparition that haunted the space: namely, the very struggles that founded the organic movement, among other things, struggles that the marketing slogans carried on, but void of their political agency. But the declaration also expanded the range of possible activities within the space of the supermarket. Returning to Whole Foods after our conversation there, I didn’t think of shopping, but of the Diggers and our discussions as we walked through the checkout aisles without exchanging anything. The experience overwrote the established intention of a supermarket.

At Whole Foods that day, I learned from Avery that storytelling is important. And I learned that telling the time and taking sides is also about storytelling, about whose story and which version is being told. It’s about whose time it is.

Jutta Weitz sings:

Say here’s a little story that must be told

About two young brothers who got so much soul

They takin’ total control, of the body and brain

Flyin’ high in the sky, on a lyrical plane20

Now is the time, Mahagonny. It is our time.

This and subsequent section titles reprise the scene titles from Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s Mahagonny-Songspiel (1927).

See Oliver Clemens and Sabine Horlitz, “Immobilienfonds und die Privatisierung gesellschaftlichen Eigentums” (Real Estate Funds and the Privatization of Public Property), in Wohnmodelle – Experiment und Alltag, ed. Oliver Elser, Michael Rieper, and Künstlerhaus Wien (Vienna: Folio Verlag, 2008), published in conjunction with the exhibition at Künstlerhaus Wien. A bilingual (German–English) version of the essay is available at →.

See Ambit ERisk’s July 2002 case study (in German) on the bank at →.

A Debt Clock located in the federal taxpayer organization building in Berlin indicates the city’s debt in real time, including the speed of increase and the personal share of each citizen: →.

The “Not in our Name, Marke Hamburg!” manifesto was posted to the eponymous (German-language) blog in November 2009. See →.

Ibid. The English version of the manifesto—“Not in our name! Jamming the gentrification machine: a manifesto”—cited here in a slightly modified translation, appeared on the sightandsign.com website on November 23, 2009,→.

“An Evening with Jimmie Durham and Mick Taussig” (conversation, House of World Cultures, Berlin, April 29, 2010).

The only information on Botschaft available online is here: →.

More information (in German) and images of Mainzer Strasse and the eviction can be found at Umbruch Archive: →.

Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, “Alabama Song (Whiskey Bar),” Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (1930).

Avery Gordon, Keeping Good Time: Reflections on Knowledge, Power, and People (Boulder: Paradigm Press, 2004), viii.

See “Von der Margarinefabrik ins MoMa: Klaus Biesenbach erster deutscher Kurator,” RP Online, last updated November 22, 2004, →.

In a unilateral reorganization of the collectively run art venue Kunst-Werke, Klaus Biesenbach became the director of the institution in 1995. One event that prompted the protests around this peculiar takeover was the awarding of the Hanno Klein Medal to Klaus Biesenbach, Hans Kollhoff, and Gerhard Merz for “a new Gründerzeit with prominence and brutality” on June 24, 1995. Hanno Klein, a Senate member responsible for inner-city investment, was a key figure in large-scale projects such as the Daimler-Benz Building on Potsdamer Platz and the Friedrichstadtpassagen. In an interview with the magazine Der Spiegel he is quoted as saying that Berlin needs a new Gründerzeit “with prominence and brutality.” He was killed by a letter bomb on June 14, 1991. See Stefan Bullerkotte, “Gegen die ästhetische Nobilitierung der Macht: Eklat bei der Verleihung der Hanno-Klein-Gedenkmedaille,” Scheinschlag 14 (1995), →; and “Rosen für das Publikum, eine makabre Drohung für den Redner,” Art 10 (1995).

See →.

Email announcement, April 29, 2010.

William Shakespeare, The Tempest, act 1, scene 2, lines 72–76.

Georges Bataille, Sovereignty, in The Accursed Share, Volumes II & III, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Zone Books, 1992), 198.

The declaration, by Gerrard Winstanley, is available at →.

The Roots feat. Mos Def, “Double Trouble.”