Paris, 19.6.2009

Subject: Clifford Irving Show

Dear Clifford Irving,

No matter how familiar Paris feels—and after all this time there are days in which its monotonous, elegant beige-stone skin fits like a kid glove—I still always manage to lose my bearings in the coiled and cobbled inclines of Montmartre. Since I landed in this city fifteen years ago, I’ve lived alone in a cramped and dim illegal sublet a minute’s walk from the red-light district Pigalle. Despite my geographical proximity to the hilltop neighborhood just north of here, there was a time I never ventured further than my late-night tobacconist on the Boulevard de Clichy. I frequented that particular tobacconist because his is the nearest of three local shops to a pitiful, barren plinth that once hosted a statue of Charles Fourier (1772–1837).1 During the Nazi Occupation of France (1940–1944), poor, utopian Charles, like so many of his bronze compatriots, became bitter metallic grist for the war mill.

In the past, the east–west axis of the boulevard incised a horizontal boundary on a mental map I had drawn of safe spaces and spaces where I could be at risk, much like the Seine River divides the Left and Right Banks. The hill to the north of the boulevard was off-limits. Christened the Mons Martyrum after the bishop of Paris Saint Denis was martyred there (ca. 275), legend has it the decapitated Saint Denis trekked two miles north with his head in his hands, accompanied by angels, to the site where his namesake church would be built. I was not bothered by the hordes of tourists seeking ersatz traces of bohemian life around the Moulin Rouge, the Lapin Agile, and the Place du Tertre, immortalized by the Montmartre school of painters. In my state, I wouldn’t have noticed them. Instead, it was the Sacré Cœur basilica, with its great white cupola soaring up like God’s blanched phallus, that repelled me. Back then I could never shake the feeling that it was standing guard expectantly, wanting me to succumb and worship it on my knees. I instinctively knew I should not get too close, or I would be doomed.2

Most nights I would drink cheap red wine until I had developed a soft buzz, before leaving the apartment to replenish my cigarettes. Then I would begin my ritual trudge east along the Boulevard de Rochechouart, eyes to the ground to avoid glimpsing Sacré Cœur. The pull of the Sacred Heart faded once I reached the bright Tati department store, which sits on the corner of the grimy Boulevard Barbès like a giant crate overflowing with a kaleidoscope of peddler’s wares. From there, I’d veer diagonally toward the derelict 1920s cinema, Le Louxor, with its neo-Egyptian mosaics all in disarray, and walk down to my regular haunt, the Gare du Nord. I went to the station because I found its stern rooftop row of sentinel Queens comforting, and because the dank, echoing bleakness of the interior matched my own. Night after night I’d sit there for increasingly long stretches, smoking and watching and waiting. In retrospect, I see that it was an alternative form of penance, as well as an urgent form of procrastination.3 I was procrastinating on my return to sanity; I sat there and poked at its possibility, like a tongue that unintentionally probes a rotten tooth and instantly retracts at the pain.

Occasionally, and to my great surprise, smart-suited businessmen would try to pick me up. They must have presumed from my regularity that I was working the station. Even if they were staying in nearby hotels I chastely only ever accepted to cross over to the café Terminus Nord. From there, my precious Queens and I could keep our eyes on each other. While it is generally agreed I am a well-read person, and though I am fluent in several European languages, nights were the regimented time in which I could release the seething incoherence that had swelled, during the day, in a tiny space I pictured as a stage prompter’s trapdoor in my brain. I am by nature taciturn, but in the evenings a perfectly random cue could release an endless staccato torrent of nonsense. My gibberish and, I suppose, the suffused weight of my physical passivity, which were cloaked behind my pleasantly average figure and features that betrayed no illness, caused these men to flee. I’d return to a bench by the tracks and sit and smoke distractedly4 until my fingers yellowed and stunk rankly of ash and I sensed daybreak. I so desperately wanted to leave, I longed to be one of those admirable, shiny, buoyant girls who just hop on a train destined for adventure, but I’ve always had trouble with departures.5

In the morning, I would heave my chilled and creaky bones out of the station and use the slow return home to recompose a presentable self.6 After sour black coffee and a scalding shower, I’d embark on another day of “research” in the Labrouste reading room at the Bibliothèque Nationale. At the time, I was financed by a scholarship and feared The Foundation might discover my predicament. I was not ready to be rescued; that would come much later. I would meticulously fill out the paper request slips and deliver them wordlessly to the punctilious librarians on their perches. When my books arrived I spent my time feverishly filling notebooks with literary and philosophical citations that both corresponded to and fed my decaying state of mind.7 I no longer possessed words of my own for what I was feeling; I had become alien to myself.8 Remarkably, I had successfully compartmentalized myself for two different publics—the peers I might encounter during the day and the nameless crowd9 that passed through the train station, and through me, at night. Two mirrored halves, one functional, one collapsing, held apart by an electromagnetic strength of will.

By now, Mr. Irving, you are surely wondering what any of this has to do with you. It has nothing to do with you at all, and yet, because you are the sole conduit for its expression, you are everything to it. Such is the curious plight of the surrogate. Though your reputation precedes you and was already known to me through a viewing of Orson Welles’ film F for Fake (1974),10 which I saw on an outing with my father when I was a schoolgirl, I had tucked the facts of your life away, including your authorship of Fake! The Story of Elmyr de Hory, the Greatest Art Forger of Our Time, and your Autobiography of Howard Hughes.11 Then, last night I found myself standing on a backstreet in Montmartre in front of the Ciné 13 theatre, which crouches in the shadow of Sacré Cœur, shyly clutching a black-and-gold, faux-art-deco-style invitation to the “Clifford Irving Show.” And your name, and this soirée, unleashed a flood of associations and involuntary memories12 that I am starting now to work through,13 and which I feel compelled to share.

It was a most extraordinary thing. I can say that on this occasion I did not go to this theatre of my own volition and have no recollection of the journey or of who may have thrust this card into my hand. What I recall is this: yesterday afternoon I went alone to the Gustave Moreau atelier-museum and got lost in reverie while admiring the thick and lustrous coat of the black feline in the right foreground of the artist’s painting Salomé Dancing Before Herod (1876).14 The next thing I knew night was falling and I was standing at the edge of a cluster of young, attractive men and women, who appeared to be well acquainted with each other and, through their chatter, I discerned, with you. These sorts of lapses in my consciousness still occasionally occur. However, I was not frightened but rather intrigued, since, in the past, their consequences have proven quite significant après-coup.15

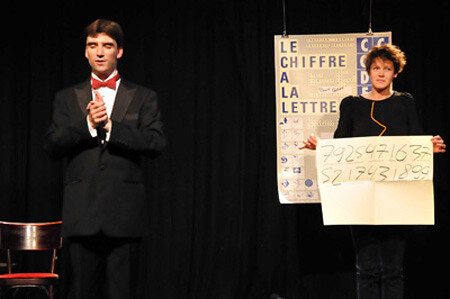

It was a typical June night in Paris: quite warm, but with tickling tendrils of cooler air, wafting out of cellars and swirling around bare ankles. Inside, the small black, red, and gilt theater was infernal;16 it was as if all the heat from the day had conspired to gather and stagnate in that one place. Shifty glances and murmured complaints were exchanged as the audience took their seats; its anticipation and discomfort were palpable. I kept to myself, as usual. A springy jazz piano and drums sliced through the thick air. I found a place near the exit, fearing I might be overcome with torpor or a sudden need to escape. The Master of Ceremonies, dressed casually, left the drum set he had been playing, to welcome the guests with a humorous flourish.

I will not provide an extensive report of the three and a half hours I spent fixated on the stage; in fact the details of the show are of quite secondary importance. However, I will now sketch for you some thoughts and provisional conclusions about this soirée.

Billed as a variety show, the program notes for the “Clifford Irving Show” posed the following question: “Where do authors go when characters interrupt the story?” This question affirms that a character is not an author’s invention, but has agency that determines plot, a commonplace notion that is repeatedly borne out in literature, as well as in autobiography,17 as you well know. Upon reading this, I was prepared for a certain narrative aspect to the evening of performances; and, indeed, the spoken word, to varying effect, dominated: texts were declaimed, mostly from printed sources, words were ventriloquized, tales were told. Please, you must not interpret “to varying effect” as criticism.18 Some people are more adept at throwing their voices than others; some are keener improvisers; some are altogether lacking as performers. I belong to the latter group and so my relationship to the stage is necessarily skewed by the most debilitating combination of longing and repression. As a child, whenever I would express my truest emotions my parents would declare me a consummate actress. I believed them, so imagine my surprise when, years later, my acting teacher dispensed with me as too emotionally glib to ever hit the boards. I do not suffer from stage fright, but since I have always been told I am too much or too little, I have opted for the wings over any sort of spotlight.

But I digress.

Several performances in the “Clifford Irving Show” were entertaining enough to divert my attention from the rivulets of perspiration that coursed down my sides: I enjoyed the magician of the mind, I admired a sensual, writhing dancer who combined her gestures with words, and I empathized with the nervousness of the sculptress unveiling her work; she moved me more than any other, perhaps because it seemed harder for her than for most. By contrast, I hated the vulgarity and delivery of the jokes. A vulgar joke is only successful if its delivery is elegant and practiced. I loved the bearded English fellow’s performative reading of a long manifesto, entitled “Black Dada,” the only title I remember. By contrast, I hated the joke he ended with, despite its elegant and practiced delivery. Mostly, I sat in wonder at the collective display of lack of inhibition.

By intermission, I had grasped that attaining a form of artistic perfection was hardly the point of this gathering of friends. There was an outline, but no script. Evaluating it from an assumed position of critical “authority” would serve no purpose. In fact, it seemed the whole event emphasized and undermined the fragile fiction of critique. This intrigued me and I chose to stay. In such an artless, amateur space, the audience and the performers become conjoined by a pact that suspends their normal positions of expertise, of judgment, of talent. Nobody is acting; everyone resolves into a stuttering self-portrait, a narcissistic staged self, a projected ideal self, a self that is able to accept its limitations. Prosopopoeia is our dominant trope. We are all the products of ghostwriting. To my patched-together psyche, witnessing this liberty of self-representation was exhilarating.

Once the show ended, I cut across the plaza in front of Sacré Cœur and joined the throng that had assembled there to gaze down at the city. My back to the church, it occurred to me that the “Clifford Irving Show” reveals that the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, the stories of defeat and discovery that help and harm us, the stories we tell others about ourselves will only ever be partial, and it does no damage to make them public. If this “Clifford Irving Show” can indeed be said to “represent” you, it is only as a cobbled construction, built out of some legendary or traceable fragments of a life, teased from documents and oral histories, edited, filtered, and subject to montage by multiple authors. You were performed last night, yet these filtered fragments are in no way “evidence” of you, and this is not because you trafficked in hoaxes or half-truths, but because you trafficked in autobiography.19 I realized, as I moved toward home, that it is really high time I change my story. And so I will.

Yours truly,

Vivian Rehberg

“Stylistic quirks reminiscent of Jean Paul. Fourier loves preambles, cisambles, transambles, postambles, introductions, extroductions, prologues, interludes, postludes, cismediants, mediants, transmediants, intermedes, notes, appendixes.”; “Fourier recognizes many forms of collective procession and cavalcade: storm, vortex, swarm, serpentage.” Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999), 642 (W13,3 and W13,5).

“O, what a noble mind is here o’erthrown / The courtier’s, scholar’s, soldier’s, eye, tongue, sword, / Th’ expectancy and rose of the fair state,/ The glass of fashion and the mould of form, / Th’ observed of all observers, quite, quite down! / And I, of ladies most deject and wretched, / That sucked the honey of his music vows, / Now see that noble and most sovereign reason, / Like sweet bells jangled, out of tune and harsh, / That unmatched form and feature of blown youth / Blasted with ecstasy. O, woe is me / T’ have seen what I have seen, see what I see!” William Shakespeare, Hamlet, ed. William Farnham (Baltimore: Penguin, 1957), act 3, sc. 1, lines 150–61.

“We have a task before us which must be speedily performed. We know that it will be ruinous to make delay. The most important crisis of our life calls, trumpet-tongued, for immediate energy and action. We glow, we are consumed with eagerness to commence the work, with the anticipation of whose glorious result our whole souls are on fire. It must, it shall be undertaken to-day, and yet we put it off until to-morrow; and why? There is no answer, except that we feel perverse, using the word with no comprehension of the principle. To-morrow arrives, and with it a more impatient anxiety to do our duty, but with this very increase of anxiety arrives, also, a nameless, a positively fearful, because unfathomable, craving for delay. This craving gathers strength as the moments fly. The last hour for action is at hand. We tremble with the violence of the conflict within us—of the definite with the indefinite—of the substance with the shadow. But, if the contest has proceeded thus far, it is the shadow which prevails,—we struggle in vain. The clock strikes, and is the knell of our welfare. At the same time, it is the chanticleer-note to the ghost that has so long over-awed us. It flies—it disappears—we are free. The old energy returns. We will labour now. Alas, it is too late!” Edgar Allan Poe, “The Imp of the Perverse” (1850), in Edgar Allan Poe: Poetry and Tales, ed. Patrick F. Quinn (New York: Library of America, 1984) 828.

“Weren’t you always distracted by expectation, as if every event announced a beloved?” Rainer Maria Rilke, “The First Elegy,” in Duino Elegies (1922), trans. Stephen Mitchell, available at href=”http://homestar.org/bryannan/duino.html”>→.

“My life closed twice before its close; It yet remains to see / If Immortality unveil / A third event to me.” Emily Dickinson, “My life closed twice before its close” (1896) in Final Harvest: Emily Dickinson’s Poems, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (Boston: Little, Brown, 1961), 314-5.

“Who am I? If this once I were to rely on a proverb, then perhaps everything would amount to knowing whom I haunt.” André Breton, Nadja (1928), trans. Richard Howard (New York: Grove Press, 1960), 11.

“So little is known about the psychology of emotional processes that the tentative remarks I am about to make on the subject may claim a very lenient judgment. The problem before us arises out of the conclusion we have reached that anxiety comes to be a reaction to the danger of a loss of an object. Now we already know one reaction to the loss of an object, and that is mourning. The question therefore is, when does that loss lead to anxiety and when to mourning. In discussing the subject of mourning on a previous occasion I found that there was one feature about it which remained quite unexplained. This was its peculiar painfulness. And yet it somehow seems self-evident that separation from an object should be painful. Thus the problem becomes more complicated; when does separation from an object produce anxiety, when does it produce mourning, and when does it produce, it may be, only pain?” Sigmund Freud, Inhibitions, Symptoms, and Anxiety (1926), trans. Alix Strachey (London: Hogarth Press, 1936), 166.

“In a way, they seemed to be arguing the case as if it had nothing to do with me. Everything was happening without my participation. My fate was being decided without anyone so much as asking my opinion.” Albert Camus, The Stranger (1942), trans. Matthew Ward (New York: Random House, 1989), 98.

“What men call love is a very small, restricted, feeble thing compared with this ineffable orgy, this divine prostitution of the soul giving itself entire, all it poetry and all its charity, to the unexpected as it comes along, to the stranger as he passes.” Charles Baudelaire, “Crowds,” in Paris Spleen, (1869), trans. Louise Varèse (New York: New Directions Publishing, 1970), 20.

“In attempting to explain F For Fake’s state-side failure, it has occurred to me that perhaps the subject matter was at least partially to blame, and that this country is so blissfully enslaved by the notion of the special sanctity of the expert that an overtly anti-expert film was bound to go too much against the national grain.” Orson Welles (1983), available at →.

“We sense a man persistently escaping the mould he’s being cast in. The story confirms that anyone can fake the lecture but it takes a superior imposter to fake the thinking.” Clifford Irving, Phantom Rosebuds (San Francisco: New Langton Arts, 2008).

“For a long time I would go to bed early. Sometimes, the candle barely out, my eyes closed so quickly that I did not have time to tell myself: ‘I am falling asleep.’ And half an hour later the thought that it was time to look for sleep would awaken me; I would make as if to put away the book which I imagined was still in my hands, and to blow out the light; I had gone on thinking, while I was asleep, about what I had just been reading, but these thoughts had taken a rather peculiar turn; it seemed to me that I myself was the immediate subject of my book: a church, a quartet, the rivalry between François I and Charles V.” Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time: Swann’s Way (1913), trans. C. K. Scott Moncrieff and Terrence Kilmartin, rev. D. J. Enright (New York: Random House, 1992), 1.

“This working-through of the resistances may in practice turn out to be an arduous task for the subject of the analysis and a trial of patience for the analyst. Nevertheless it is a part of the work which effects the greatest changes in the patient and which distinguishes analytic treatment from any kind of treatment by suggestion.” Sigmund Freud, “Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through: Further Recommendations on the Technique of Psychoanalysis” (1914), in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. and trans. James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press, 1986), 12:155–6.

“The discovery of the Musée Gustave Moreau, at around the age of sixteen, influenced forever the way I love … It goes so far that these kind of women probably concealed all the others, yes, I was completely bewitched.” André Breton, Manuscript: À propos de Gustave Moreau (1950).

“Après-coup (subst. M., adj. and adv.). Translation from the German Nachträglichkeit: Term frequently used by Freud in relation to his conception of temporality and psychic causality: experiences, impressions, memory traces are reformulated later depending on new experiences, and their accessibility to another degree of development. It is then possible for them to obtain a physic utility as well as new meaning.” Jean Laplanche and Jean-Bertrand Pontalis, The Language of Psycho-analysis, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (New York: Norton, 1974).

“I once came close to a conversion to the good and to felicity, salvation. How can I describe my vision, the air of Hell is too thick for hymns! There were millions of delightful creatures in smooth spiritual harmony, strength and peace, noble ambitions, I do not know what all?” Arthur Rimbaud, A Season in Hell, trans. Paul Schmidt (New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1976).

“Autobiography seems to depend on actual and potentially verifiable events in a less ambivalent way than fiction does. It seems to belong to a simpler mode of referentiality, of representation, and of diegisis. It may contain lots of phantasms and dreams, but these deviations from reality remain rooted in a single subject whose identity is defined by the uncontested readability of his proper name … but are we so certain that autobiography depends on its subject or a (realistic) picture of its model? We assume that life produces the autobiography as an act produces its consequences, but can we not suggest, with equal justice, that the autobiographical project may itself produce and determine the life and that whatever the writer does is in fact governed by the technical demands of self-portraiture and thus determined, in all its aspects by the resources of his medium?” Paul De Man, “Autobiography as De-facement,” in MLN 94, No. 5 (December 1979): 920.

“Such reflections lead me to the conclusion that criticism, abjuring, it is true, its dearest prerogatives, but aiming, on the whole, at a goal less futile than the automatic adjustment of ideas, should confine itself to scholarly incursions upon the very realm supposedly barred to it, and which, separate from the work, is a realm, where the author’s personality, victimized by the petty events of daily life, expresses itself quite freely and often in so distinctive a manner.” “We have said nothing about Chirico until we have taken into account his personal views about the artichoke, the glove, the cookie, or the spool. In such matters as these, how much we could gain from his cooperation! As far as I am concerned, a mind’s arrangement with regard to certain objects is even more important than its regard for certain arrangements of objects, these two kinds of arrangement controlling between them all forms of sensibility.” Breton, Nadja, 13, 16.

“By making autobiography into a genre, one elevates it above the literary status of mere reportage, chronicle, or memoir and gives it a place, albeit a modest one, among the canonical hierarchies of the major literary genres. This does not go without some embarrassment, since compared to tragedy, or epic, or lyric poetry, autobiography always looks slightly disreputable and self-indulgent in a way that may be symptomatic of its incompatibility with the monumental dignity of aesthetic values.” De Man, “Autobiography as De-facement”: 919.