Why does almost everything seem to me like its own parody?

—Adrian Leverkühn in Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus

1. The Evanescent

The “Floating World” or “Ukiyo” is the name commonly given to the demimonde of nocturnal pleasures that flourished in Edo-period Japan (1603–1868), specifically in Tokyo’s historic red-light district of Yoshiwara; this era is best remembered today for the flowering of the art of woodblock prints (“ukiyo-e”) that depict various aspects of the Floating World’s daily life, such as kabuki theatre, sumo wrestling, and the secretive world of geishas and courtesans. The Floating World derives it name from its fascination with all things fleeting and evanescent: outward beauty, “singing songs and drinking wine,” superficial entertainments, sexual pleasure. Some ukiyo-e artists’ concentration on the latter category in particular (erotic woodblock prints or “shunga”) has led some commentators to characterize this dimension of Edo culture as an early exercise in creating a “pornotopia”—an idealized, eroticized world of sexual fantasy that exists parallel to the world of mundane contemporary concerns.1

For this reason alone—the relentless pornofication of all aspects of everyday life—it is tempting to call our contemporary world a “floating” one, much like that of Hiroshige’s or Hokusai’s Japan. Indeed, if today we find it increasingly difficult to define or describe both the era and the world we live in, if a sense of unmooring, drift, directionlessness, and general confusion seems to have grabbed a stifling hold of our imagination in all its attempts to map the contemporary life-world, this is probably a side effect of our living in a twenty-first-century “floating world”—one that is not only ruled by the tyranny of superficial entertainments (to which most art now is happy to belong), but one that is also radically—and no longer just hopefully—afloat.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Ligurian Sea, Saviore, 1993. Gelatin silver print, 47 x 58 3/4”

2. The Oceanic

In a recent conversation with a writing and curating colleague, we both agreed that a strange, and strangely immobilizing, mist had descended upon our little pocket of this world—a fog seemed to have enveloped the hearts and minds of those customarily expected to both shape the present (if only in theory) and imagine the future (if only in practice). The resulting experience of disorientation is nothing new, of course, but perhaps the thickness of this particular miasma is such that we really have no idea where we’re going anymore. Although this can probably be proven to have good (or at least aesthetically pleasing) effects in some fucked-up way or other, for now we must admit that it is mostly a bad thing.

This foggy state of affairs made us think of the work of Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto, the still-active photographer of (mostly mist-shrouded) seascapes. We were both surprised to discover how Sugimoto suddenly emerged as being so truly contemporary, a deft chronicler of a mental state in and of the Now—a new “oceanic” feeling.2

From left: poster for The Fog, 1980, Directed by John Carpenter; poster for The Fog, 2005, Directed by Rupert Wainwright.

3. The Vertiginous

Indeed, one would be hard-pressed to call the aforementioned experience of “drift” or “unmooredness” truly novel. Leo Charney, a film theorist at the University of New Mexico, has authored a study titled Empty Moments in which he calls drift the defining quality of modernity—the experience of being unable to locate a stable sense of the present:

If the philosophy and criticism of modernity were preoccupied with the loss of presence, where can we go conceptually after acknowledging that presence irrevocably becomes absence? Once we have recognized that presence cannot coincide with itself, that sensation and cognition are always already alienated, that the body lives in self-segregation, are we left with no epistemological alternatives other than to repeat these premises again and again like a mantra? Is this all there is to say about the absence of presence as an experiential condition of modernity? As each present moment is remorselessly evacuated and deferred into the future, it opens up an empty space, an interval, that takes the place of a stable present. This potentially wasted space provides an opening to drift, to put the empty present to work not as a self-present identity or a self-present body but as a drift, an ungovernable, mercurial activity that takes empty presence for granted while maneuvering within and around it.3

Thus far Charney’s modern view of drift as a site of great potential appears akin to Adorno’s claim for vertiginousness, but the former’s emphasis on movement in this brief characterization will already have signaled its massive difference from today’s drifting into the thickening fog of the here and now: no one would use the words “mercurial,” “activity,” or “maneuvering” to describe the total paralysis felt in the face of the present; today’s drift, the feeling of being trapped in one of Sugimoto’s horizonless seascapes, is anything but an ungovernable activity—it is itself the governing force, the rule rather than a riot of exceptions that challenge it. Drifting clouds no longer figure as the fleeting ciphers of a utopian weightlessness; they now weigh down upon us in turn, immobilizing us with the sheer volume of what was once casually called a swarm of “floating signifiers,” rendering everything around us opaque rather than transparent, invisible rather than visible: a quagmire rather than a “floating world.”

From left: Poster for the 2007 film The Mist; cover of Stephen King’s The Mist.

4. The Olympian

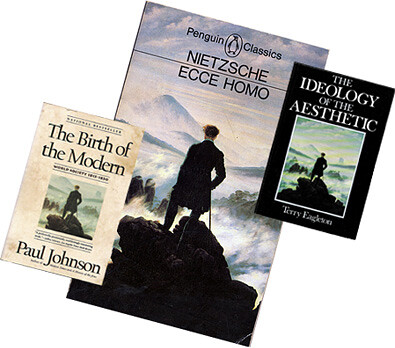

The Wanderer Above the Mists is undoubtedly Caspar David Friedrich’s most famous painting, and probably also the one painting that comes closest to defining or embodying the (original) Romantic spirit in European culture. It graces countless book covers on or related to the subject of Romanticism, from Paul Johnson’s Birth of the Modern (on the Right) to Terry Eagleton’s Ideology of the Aesthetic (on the Left) and all the Nietzsches and Schopenhauers in between, and it also appears on many a classical music album cover (Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann). The identity of the wanderer imperiously looking down upon a sea of clouds—a singular mark of his individuality—is shrouded in historical mystery, as is the exact location of this primal scene of man’s showdown with the sublime. But a view from or towards Jena it is not—that would have been an unobstructed one, showing the Thuringian town basking in the soft late-afternoon light of unclouded reason.4

Today, we are all wanderers in the mist: Friedrich’s Olympian viewpoint appears to have been irretrievably lost. And this experience (of loss, of submersion) has, of course, much aesthetic potential of its own—its allure is all too well known.

5. The Reticular

To be in the midst of things, or to be engulfed by them: for some twenty years now (that is to say, since art became truly “contemporary”), “immersion” has been the object of a singularly powerful directive in art production. White cubes have become black boxes, environments interactive, institutions self-critical, and aesthetics relational: art, in all these instances, has become that which surrounds us, a world unto itself as much as, if not more than, some-thing in this world alongside ourselves. (We rarely stand opposite things anymore, and when we do, the thing is mostly considered retrograde, if not a remnant of reaction, or else our position is thought of as such: the promotion of clear-cut subject-object relations in art is best left to historical museums.) This emergent rhetoric of emancipation through immersion is of course deeply linked to the rise of the network as the defining paradigm of a new economy rooted in information, immaterial labor, and the speedy transport of ideas.5 “Connectivity” and “mobility” are the reticular paradigm’s greatest assets, or at the very least constitute its grandest claims—but anyone who logs onto the internet, the paradigm’s most successful and thorough incarnation, intuitively grasps the true meaning of the medium’s steady transformation from a utopia of mobility to a dystopia of absolute immobility (though this last qualification seems to suggest that all immobility is innately evil, which it evidently isn’t): in “entering” the network, he or she has just stepped into the same thickening fog that art does so well to sell back to us as the height of contemporary (syn)esthetic experience.

6. The Inflationary

In a previous essay for e-flux journal, I suggested that contemporary art and the contemporary art world may essentially be the same, and that that is not a good thing—not for art anyway (it is, conversely, a good thing for the art world—without a doubt).6 Today, this confusion does not merely manifest itself in the profusion of writing that talks about the art world while deluding itself that it talks instead about art (mine could be called a case in point, but that is up to the reader to decide), it is also plainly manifest in the vast quantities of art made “about” the art world—an inflationary category that also includes most art-about-art (compare this with the hypertrophy of “referentiality” in contemporary art, as well as with the tiresome historical overestimation of “institutional critique”)—and in the ubiquity of “immersion” as a theatrical (and not merely curatorial) strategy. To a certain extent, art’s gradual obscuration by the art world is the natural consequence of the world’s equally natural desire to be close to art, to become one with it (for it is most certainly a desirable topos): just like we can own art objects (even the most immaterial ones, even if they are only “ideas”) but not art, so we can also inhabit the art world rather than art—but the distinction, no matter how crucial, obviously loses much of its significance when the idea of the art world starts to eclipse the idea of art, and all we are left with is the system rather than the concept. This is not a good idea: the concept must be saved from, and either protected or defended against, the system.

From left: Ann Veronica Janssens, MUHKA, 1997; Robert Morris Steam, 1967/2009.

7. The Atmospheric

In that previous essay, I suggested that “art is the word, or, better still, the name of a great theme, of mankind’s greatest idea, its single lasting sentence”—and who would disagree? In a lecture I attended in London a couple of months ago, Susan Buck-Morss noted how “horrors have been committed in the name of ‘culture,’ but never in the name of ‘art.’” (Of course, Buck-Morss failed to acknowledge the horror of much art as such—perhaps the occasion was too solemn for such witticisms: she had been invited to talk about her new book Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History, published just months before the catastrophic earthquake hit the Caribbean nation.) For that reason alone, it is perhaps worth protecting art from the world that wants to encroach upon it and remake it in its own depressing image—from the pressure exerted by the myriad institutions that, as so many emblems of “culture,” have sprung up around the idea of art to coalesce in the master institution that is the art world.

In 1964, Arthur C. Danto published an influential essay titled “The Art World,” the first text to more or less theorize the phenomenon, in direct response to his epiphany-like experience of seeing Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes for the first time. In this essay, Danto famously coined the formula “an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld” as an answer to the question as to what was needed to be able to see Warhol’s installation of Brillo boxes as a work of art (as opposed to the original Brillo boxes, which were designed, ironically, by a middling Abstract Expressionist named James Harvey). That he should have used the term “atmosphere” to describe this system now seems uncannily prescient—a prophecy of enveloping mists, fogs, fuzzinesses, and other dematerializations to come, many of which were meant to assure his audience that the idea of art would not only collapse into an art world, but that this art world would in turn shrink further still to become equated—in a properly post-Warholian, post-Factory manner (the “factory” is Warhol’s well-chosen name for his diminished view of the possibilities of the idea of the art world)—with an art market.

8. The Nebulous

One day, the epistemology of confusion and disorientation—along with its corollary theorizations of access and accessibility; complicity and connectivity; enfolding and implication; participation, porosity, and proximity; telephony and transience—will be remembered, less for its (worthwhile) contribution to the history of both critical practice and theory than for the sophistication with which it helped to dismantle the grand étatiste apparatus of the dialectic. To no longer see anything clearly anymore means precisely this: to no longer perceive things as discrete entities and oppositional realities. And what has disappeared in the haze that fills today’s art world (or that is today’s art world), is both the work of art as such a discrete entity—it has long been eclipsed by a nebula named “practice”—and the idea of art as such an oppositional reality: sadly, neither are wholly “other” any longer.7

Mina Totino, Vancouver Clouds, 2000-2003. Polaroid photographs, installation view.

9. The Faustian

Some hundred and seven years ago, Thomas Mann published a novella titled Tonio Kröger, a lazily concealed exercise in fictionalized autobiography, as was so much of Mann’s earlier (Buddenbrooks) and later (Death in Venice) work. It was in regard to this story that Georg Lukács, Mann’s most formidable (but ultimately sympathetic) critic, identified the so-called “Tonio Kröger problem” as a motif recurring in much of the writer’s literary output, from Tonio Kröger itself to Doctor Faustus. This problem concerns the artist’s dilemma in facing the art/life dichotomy, which Tonio Kröger articulates most directly in his dialogue with his bohemian Russian artist friend Lisaveta Ivanovna (the same name, incidentally, that was given by Dostoyevsky to one of Raskolnikov’s two victims in Crime and Punishment):

There is no problem, indeed nothing in the world, that is more tormenting than the issue of art and its effect on humanity… . Life is the eternal antithesis to intellect and art … What would be a more lamentable sight than life trying its hand at art? … You have to be some kind of nonhuman and inhuman thing, you have to have a strangely distant and neutral relationship to the human, in order to be able, to be even tempted, to play it, to play with it, to depict it effectively and tastefully… . An artist stops being an artist the instant he becomes human and starts feeling.8

Mann would go on to develop this complex with chilling comprehensiveness in his Doctor Faustus, the definitive portrait of genius (that is to say, art) succumbing to the madness of an anti-humanist fascism—yet even then and there, the great writer acknowledged that he was essentially composing a self-portrait. Like Adrian Leverkühn, the central figure of Mann’s awesome contribution to Germany’s national myth of the Faustian bargain and “merely a younger brother of Tonio Kröger and [Death in Venice’s] Gustav von Aschenbach,” Mann wonders aloud: “How then is it possible to create music of a really high artistic order without breaking free of one’s time, without firmly and actively renouncing it?”9 Leverkühn’s answer is a resounding No (“It is not possible …”), and so he sets off, in splendid isolation,10 to scale the dizzying heights of Caspar David Friedrich’s ancient mountain range, where the air is rarefied and icily pure, and the view unimpeded. Yet once the wanderer has reached his final destination “above the mists,” he finds that almost everything seems to him like its own parody—everything, that is, except his own remoteness: that which affords him a crystal-clear view of art as opposed to the world.

10. The Meteorological, The Ironic, and the Abysmal

“The atmospheric pressures of artistic theory,” to paraphrase Danto, is an apt description, in its meteorological flair, of the rise of “theory” proper, and of the conditions that led to the demise of theory’s symbolic obverse, the dialectic—the “grasping of opposites in their unity or of the positive in the negative.”11 The bracketed notion of “theory,” of the kind so eagerly consumed in today’s art world, is the discursive equivalent of the pervasive condition (itself oft-rendered in quasi-meteorological terms12) of immersion and relational implication; the theorist is, by the very definition of theory’s resistance to definitions, always already embedded. For reasons that are in many ways too obvious to expound on here—suffice it to say that they are mainly connected to issues of power and the natural longing for what Adrian Leverkühn called the “cow warmth of music,” as well as for the aforementioned “pornotopia”—this makes “theory” a lot more attractive than the dialectician’s impossible insistence on the so-called illusion of critical distance, which, as an ideological fabrication of sorts, has indeed been the subject of much (equally ideological, yet no less deserved) bad press of late. (And for reasons that relate to the oppressive economic reality of the network—and of its governing logic, named globalization—it is clear why distance as such should be deemed both impossible and outdated, or why we would be discouraged to dream of Friedrich’s detached Olympian viewpoint: there are no opportunities for shopping “there.”) It is precisely along these journalistic lines that Fredric Jameson, in his bewildering Valences of the Dialectic, notes that “it is certain that today self-consciousness … has bad press; and that if we are tired enough of philosophies of consciousness, we are even more fatigued by their logical completion in reflexivities, self-knowing and self-aware lucidities, and ironies of all kinds.”13 And so we arrive at our final destination, namely Grand Hotel Irony, just down the road from Grand Hotel Abyss—and how very unsurprising that it should be bathing in the late-afternoon glow of “self-aware lucidities,” which perhaps begs one question above all: whence our fear of the light?

See Timon Screech, Sex and the Floating World: Erotic Images in Japan 1700–1820 (London: Reaktion Books, 2009).

I would like to thank Charles Esche for sharing his thoughts on mist (and Hiroshi Sugimoto) with me.

Leo Charney, Empty Moments: Cinema, Modernity, and Drift (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1998), 6–7.

See my “What is Not Contemporary Art? The View from Jena,” e-flux journal, no. 11 (December 2009), →.

I am aware that I am talking, in part, about e-flux itself.

See note no. 4.

With the “work of art” I mean both the artwork that is the product or outcome of the production process, as well as this production process as such—work as labor.

Thomas Mann, Tonio Kröger, in Death and Venice and Other Tales, trans. Joachim Neugroschel (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books, 1998), 187, 190, 193, 194.

Georg Lukács, “The Tragedy of Modern Art,” in Essays on Thomas Mann (New York: The Universal Library, 1965), 65.

It is worth remembering here that none other than Theodor Adorno was Mann’s primary source of musicological intelligence while composing Doctor Faustus during his Californian exile.

This is probably the most concise definition of a notoriously elusive, properly “dialectical” term—as found in Hegel’s Logik. See Hegel’s Science of Logic, trans. A. V. Miller (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1989), 56.

The single most powerful example of this condition remains for me Olafur Eliasson’s Weather Project, “on view” at Tate Modern in the fall of 2003.

Fredric Jameson, Valences of the Dialectic (London and New York: Verso, 2009), 281.