→Continued from “Innovative Forms of Archives, Part One: Exhibitions, Events, Books, Museums, and Lia Perjovschi’s Contemporary Art Archive” in issue 13.

Historiography, as Igor Zabel wrote, never was and never is a neutral and objective activity:

It is always a construction of an image of an historical period or development … This construction plays a specific role in the symbolic and ideological systems, throughout which various systems of power manifest themselves on the level of public consciousness. The fields of culture and art, thus art and cultural history, are those spheres where it becomes evident how the systems of power function symbolically. They namely construct stories and development systems and, simultaneously, present them as “objective” facts. Those viewpoints, that are incompatible with such constructions, are, on the other hand, marginalised, hidden or excluded.”1

An awareness of the conditions and manipulations involved in the emergence of documents or works of art, which are then officially presented as “objective facts,” offers a means of contextualizing the ideas and knowledge that we inherit through education and society at large. Following Lia Perjovschi’s mapping of what a subjective art history can accomplish, two other projects offer some perspective on expanding archives and contest the hardening of grand (art) historical narratives imposed by either “colonizers” from Western Europe and the U.S. (in the case of the group IRWIN) or “colonized” local art historians (in the case of Tamás St. Auby). For the past decade, in the context of an encounter between postcolonial and postcommunist studies, the terms of colonization—its forking historical paths, official and unofficial documents, events, and stories—have been widely discussed within Eastern European theoretical discourse. In a recent text about the post-bipolar condition of the former Eastern Bloc, Vit Havránek explains how there existed a double colonization in the Eastern European states outside the Soviet Union:

Soviet executive colonial power manifested itself across the Eastern Bloc unevenly, because it colonized countries not through direct governance, but by establishing, controlling and overseeing national governments which were subordinated to the centre in differing degrees. The “paternal nation,” along with the state apparatuses of each country, administered and adapted the colonial ideology locally according to its own needs and local conditions, translating its local languages into local laws and norms … In the satellite states, people were colonized twice—first, as historical victims of the post-war world which fell to their liberators, divested of their existing state administrations and forcibly oriented toward the historically higher-ranking ideology of communism (horizontally) and, second, by means of their own communist agitators and governments in whose hands they were subjected to a differentiated national self-colonisation (vertically).2

In opposition to the most common symptom of the colonized—the belatedness with which one’s own culture projects itself as an echo of the grand narratives—these particular artistic engagements are witnesses furthermore to the importance of documenting and disseminating the neglected chapters of art history. It might seem that the role of the artist and that of the museum have changed places. The objective of this (self-)historicizing artistic strategy is to record the parallel histories that are subjectively preserved and exist as the fragments of memories and semi-forgotten oral traditions. In her seminal essay on “interrupted histories,” Zdenka Badovinac explains that the artists thus act as ethnologists or archivists of their own and other artists’ projects that were marginalized by local politics and remained invisible in the context of international art.3 This informal historicization is, in Badovinac’s view, the point at which the Other resists its former status as an object of observation, classification, and subordination to the modernizing process, transforming instead into an “active Other.”

IRWIN, NSK Embassy Moscow, 1992; Photo: Jože Suhadolnik, 2005.

IRWIN and East Art Map

Never pretending that theirs was the ultimate story, the group IRWIN however felt itself to be at the right place at the right time to provide a research tool in the form of the ongoing project East Art Map, on which a multiplicity of subjective views and voices of different generations and opposing aesthetic views could be expanded into an art historical alternative. Already in the late 1980s the newly established IRWIN group defined its program, whose governing principles were “retro-principle,” emphatic eclecticism, and assertion of nationality and national culture. Retro-principle is defined not as a style or trend, but rather a conceptual principle, a particular way to behave and act. In a diagram created in 2003 IRWIN claimed the retro-principle to be the ultimate method of working, by way of constructing context. The principle involves three fields of interest in which IRWIN performs its artistic activities: “geopolitics” (projects like NSK Embassy Moscow, Transnacionala, East Art Map), “politics of the artificial person” (transformation of the collective Neue Slowenische Kunst, which IRWIN co-founded, State-in-time, Retroavantgarde—Ready-made avant-garde and other projects), and “instrumental politics” (IRWIN’s advisory work on several international collections, East Art Map).

When the transitional period began in the 1990s and the doors to the Western art establishment (meaning the prospect of international acclaim) were opened, IRWIN, in opposition to most, did not attempt to melt into the Western art system, but decided to continue working within their own cultural context. The basic premise was that the conditions under which artists in the East worked represented the only real capital available to them after the changes in the early 1990s. Therefore IRWIN turned to the East in order to compare their experiences with those of other artists working in the West. Based on this fundamental distinction, IRWIN labeled the artistic production of the latter “Eastern Modernism.” The term embodied a paradoxical stance towards the internationalizing and globalizing institution of (Western) modernism and represented IRWIN’s attempt to actively intervene in the grand narratives of a Western-dominated art history; it is in this spirit that they construed a fictive art movement for the geographic space of Yugoslavia, called “retroavantgarde” or “retrogarde.” Vit Havránek writes about a certain

compensatory effect which manifested itself promptly after 1989 in the satellite countries [which] was an immediate rejection of a common ideological (non)time as a colonial instrument of governance along with the need for the “return” of national temporalities to that of Western history. This process has run a very paradoxical course; the West demanded the integration of “Eastern art” as a homogenous temporality into the universal time of the First World—and continues to do so to this day, one might say.4

Irwin, Retroavantgarda, 325 x 600 cm, mixed media, 2000; Theoretician: Marina Gržinić; Including the works: Irwin, Was ist Kunst, (1984 - 1998); Dimitrij Bašićević Mangelos, Tabula rasa, m. 5, 1951-1956; Avgust Černigoj, Construction, 1924; Braco Dimitrijević, Triptychos Post Historicus, 1985 (reproduction); Laibach, Ausstellung Laibach Kunst, 1983 (exhibition poster); Kasimir Malevich (Belgrade), Paintings, 1985; Gledališče Sester Scipion Nasice, Krst pod Triglavom (Baptism under the Triglav), 1985; Jossip Seissel, Balkanite Stand at Attention, 1922 (reproduction); Mladen Stilinović, Exploitation of the Dead, 1980.

With the aim of unmasking the subjective construction of that very art history that was imposing its canons and colonizing other parts of the (Second and Third) World, IRWIN, together with their long-term collaborator and writer Eda Čufer, wrote a manifesto, The Ear Behind the Painting (1990):

During the Cold War, numerous artists emigrated to the West, and the false conviction that modern art, no matter whether coming from the East or from the West, is so universal as to be classified under a common name: the current –ism, appeared to be very common … The different contexts in which the Western and the Eastern experiments were carried out deprived modern art of its international character … With Eastern time preserved in the past and Western time stopped in the present, modern art lost its driving element—the future … The name of Eastern art is Eastern Modernism. The name of its method is retrogardism.5

IRWIN, in collaboration with the philosopher Marina Gržinić, refers to the master narrative of modernism, Alfred H. Barr’s Diagram of Stylistic Evolution from 1890 until 1935, which Barr, founding director of New York’s MoMA, developed in 1936 as a genealogical family tree of the European avant-garde movements as precursors of the abstract art of modernism; in so doing, IRWIN

with a similarly arrogant attitude … transfers this scheme onto Yugoslavia, here in the form of a reversed genealogy of the “retroavantgarde,” which extends from the neo-avantgarde of the present back to the period of the historical avant-garde. The installation Retroavantgarde … is both an independent work of art and a pragmatic, cartographic instrument … By postulating the existence of a fictive Yugoslavian retro-avant-garde, IRWIN (re)constructs and posits a modernism intrinsic to Eastern Europe. This “Eastern Modernism” however, turns out to be just as construed, fictive, and artificial as its Western counterpart.6

In a painting—and later in an installation that included original works by, among others, Mangelos, Mladen Stilinović, Braco Dimitrijević, Kasimir Malevich, and IRWIN—the artists incorporated their heroes and influences into an organized system. Moreover, as mentioned above, to Western art historians Eastern Europe has usually been considered a region where belated influences from the West were at the foundation of its own art history, and where reproductions or copies of masterpieces were seen more often than originals.7

IRWIN in collaboration with Michael Benson, Alexander Brener, Eda Cufer, Vadim Fishkin and Yuri Leiderman, Transnacionala, A Journey from the East to the West, 1994.

The East Art Map, an ongoing project started in 2002, gave rise to several exhibitions and a book published in 2006 by Afterall Press in London. In 2002 IRWIN invited twenty-three curators, critics, and art historians from Central and Eastern Europe (among them Iara Boubnova, Ekaterina Degot, Marina Gržinić, Elona Lubyte, Suzana Milevska, Viktor Misiano, Edi Muka, Ana Peraica, Piotr Piotrowski, and Igor Zabel) to each select ten artists from their respective local contexts that they considered the most crucial for the development of contemporary art in Eastern Europe. “The history of art is a history of friendship,” claims IRWIN in the first part of the East Art Map project, based on the axiom that “history is not given,” that one has to actively intervene in history’s construction. The aim of this ongoing project is to show the art of geographical Eastern Europe as a unified whole, outside any national frameworks. IRWIN writes that:

In Eastern Europe there exists as a rule no transparent structures in which those events, artifacts, and artists that are significant to the history of art have been organized into a referential system accepted and respected outside the borders of a particular country. Instead, we encounter systems that are closed within national borders, whole series of stories and legends about art and artists who were opposed to this official art world. But written records about the latter are few and fragmented. Comparisons with contemporary Western art and artists are extremely rare. A system fragmented to such an extent … prevents any serious possibility of comprehending the art created during socialist times as a whole. Secondly, it represents a huge problem for artists who, apart from lacking any solid support … are compelled for the same reason to steer between the local and international art systems. And thirdly, this blocks communication among artists, critics, and theoreticians from these countries.

Understanding history as the ultimate context, IRWIN decided to “democratize” its construction. Thus, following the official selection of the invited professionals, IRWIN established an online portal, where anyone who is interested could add proposals or suggest substitutions within the established East Art Map.8 The invitation to do so sounds even pathetic: “History is not given, please help construct it!” However, sharing the responsibility by proposing a co-authored historiography is a democratic gesture in itself. This portal is now an archive-in-progress for the forthcoming proposals and discussions about the compiled documentation. Another level of the project is represented by its installations in the gallery contexts that offer a possibility to browse through an archive of links, digitalized images, and a transparent system of selections compiled by the invited professionals. These installations are IRWIN’s artworks, as is, in its potential reading, the publication itself.

Tamás St. Auby and Portable Intelligence Increase Museum

The efforts of Tamás St. Auby (born in 1944, and also known as Tamás Szentjóby, Stjauby, Emmy Grant, St. Aubsky, and T. Taub) to correct and insert his own knowledge of works of art and art movements into the official local art history can be observed analogously to Lia Perjovschi’s appraisal of subjectivity as the axiomatic viewpoint. This major conceptual and political artist, who represents one of the most radical art positions within the Hungarian neo-avant-garde, has translated numerous Fluxus texts and was a co-organizer of the first happening in Hungary. In 1968 St. Auby founded the International Parallel Union of Telecommunications (IPUT), through which he, as the organization’s superintendent, has since performed part of his activities under the motto “All prohibited is art. Be prohibited!” In the early 1970s he developed the notion of the artist’s strike (which we encounter in 1979 in Eastern Europe with the Serbian artist Goran Djordjević and his attempt to organize an art strike on an international level) as a creative decision, which was St. Auby’s response to being strictly censored by the Hungarian authorities and arrested in 1974 due to his participation in the samizdat literature movement; a year later he was forced to leave his country. Only in the early 1990s was he able to return to Budapest.

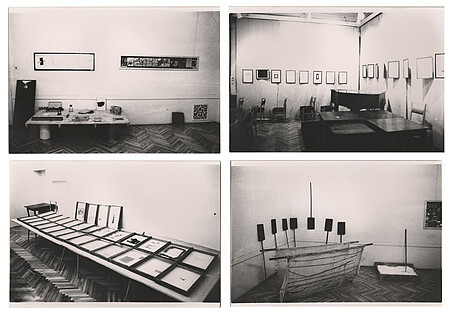

Criticizing the official Hungarian “art historical falsification,” in 2003 St. Auby created in the Dorottya Gallery in Budapest the interactive installation Portable Intelligence Increase Museum: his own database of artists working in Hungary outside and against the oppressive government system that, together with his colleagues belonging to the Neo-Socialist Realist International Parallel Union of Telecommunications’ Global Contra-Art-History-Falsifiers Front, he compiled as the true record of the “Pop Art, Conceptual Art and Actionism in Hungary during the ‘60s,” as the project’s subtitle has it. According to its authors, it spans a period between 1956 and 1976. This continuously expanding multimedia archive is made up of a walk-through wooden construction of tables and walls, and contains about seventy multiples by roughly seventy artists as well as the digitalized, projected reproductions of more than 1,100 works in all kinds of formats (paintings, photos, sculptures, objects, films, videos, poems, texts, documents). With Marcel Duchamp’s archival and autonomous Boîte-en-valise in mind, we can observe the derivation of the Portable Museum’s easily mountable structure. This counter-art-historical project was conceived with the intention of exposing the flaws in official accounts of Hungarian art of the 1960s and ‘70s by noting that the important subversive practices of the neo-avant-garde were left out of the influential publication The Primary Documents and exhibitions like “Aspects/Positions.”9 In an openly confrontational tone, St. Auby states that the art produced after the 1950s in Hungary that developed in synchrony with international trends and other suppressed experiments within Eastern Europe was not properly revealed to the public. He writes that:

It might have been covered had Hungarian art historians and curators taken upon themselves the task of informing the unaware public about domestic and foreign developments before and after the 1989 coup. The era’s Hungarian artistic developments aren’t worked up, appreciated, archived or popularized. As a consequence, the artistic common knowledge is truncated and mutilated.10

In a similar fashion to IRWIN, St. Auby makes an artistic intervention into the constitutive history of contemporary art, a constructive proposal that is no less an ambitious effort at self-institutionalization.

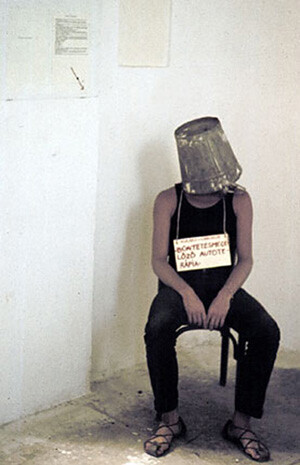

Tamás St. Auby, Retrospective exhibition, Club of Young Artists, 1975; Photos and copyright: Tamás St. Auby.

Igor Zabel, “Strategija zgodovinopisja,” in Boris Groys, Celostna umetnina Stalin (Ljubljana: Založba/*cf, 1999), 147.

Havránek refers to “self-colonization,” which is known from texts by Alexander Kiossev, but uses it in a different sense—people do not colonize unconsciously; instead, they consciously adapt the colonizer’s ideology to local circumstances. See Vit Havránek, “The Post-Bipolar Order and the Status of Public and Private under Communism,” in ThePromises of the Past, ed. Christine Macel and Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez (Paris: Centre Pompidou; Zürich: JRP – Ringier, 2010), 26.

Zdenka Badovinac, “Interrupted Histories,” in Prekinjene zgodovine / Interrupted Histories, ed. Zdenka Badovinac et al. (Ljubljana: Museum of Modern Art, 2006), unpaginated.

Havránek, “The Post-Bipolar Order,” 27.

Inke Arns, ed., Irwin: Retroprincip, 1983–2003 (Frankfurt am Main: Revolver / Archiv für aktuelle Kunst, 2003), 233.

Inke Arns, “Irwin Navigator: Retroprincip 1983–2003,” in Inke Arns, Irwin, 14.

The Belgrade Kasimir Malevich is among those behind belongs to a series of authorless projects originating fromin the Southe-Eastern Europe, active fromstarting in the early 1980s until and continuing today. Among these These projects are include Salon de Fleurus, New York, a performance by Walter Benjamin in Ljubljana in 1986,Museum of American Art in Berlin, etc. As Marina Gržinić writes: “Inthe projects of copying from the 1980s in ex-Yugoslavia the real artist’ssignature is missing and even some of the “historical” facts are distorted(dates, places). From my point of view, the production of copies and the reconstructionof projects from the avant-garde art period in post-Socialism had a directeffect on art perceived as “Institution” and against “History,” which was (andis still?) completely totalised in post-Socialism.” Marina Gržinić. “The Retro-Avant Garde Movement In The Ex-Yugoslav Territory Or Mapping Post-Socialism,”in: Inke Arns, Iop.cit., p.rwin, 220. More about these projects in the following part of this very article.

See East Art Map.

Primary Documents. A Sourcebook for Eastern and Central European Art since the 1950s, ed. Laura Hoptman and Tomáš Pospiszyl (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2002). The exhibition “Aspects/Positions: 50 Years of Art in Central Europe, 1949–1999” was chief-curated by Lorand Hegyi with many co-curators from the respective countries. The exhibition was on view at the Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig in Vienna in 1999 and at the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona in 2000.

Tamás St. Auby, “Portable I2 Museum – Pop Art, Conceptual Art and Actionism in Hungary during the ‘60s (1956–1976),” document sent to the author by the artist in 2008.

Category

→“Innovative Forms of Archives” will continue in “Part Three, Vyacheslav Akhunov’s “1 m2,” and Walid Raad’s “A History of Modern and Contemporary Arab Art: Part I_Chapter 1: Beirut (1992–2005).”