→ Continued from “Art and Thingness, Part Two: Thingification” in issue 15.

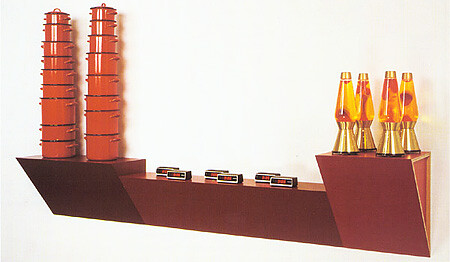

In Hans Haacke’s pieces Broken R.M… and Baudrichard’s Ecstasy from the late 1980s, Duchamp’s readymades are subjected to transformations that highlight the problematic use of the readymade in the commodity art of the era: in the latter piece, a gilded urinal sits atop an ironing board; water is pumped through it from a bucket in a closed, self-referential loop. After Warhol’s canny exacerbation of the emerging image of the commodity, and the focus on the “picture” in late-1970s Appropriation Art, the commodity art of the 1980s focused on objects once more, but this time on objects devoid of the Duchampian tension between sign and thing, between a utilitarian object and the meanings projected onto it; these objects were programmed from the beginning to signify, to create value through the theological whims of their designed interplay. While Haim Steinbach’s shelves demonstrate this mechanism with considerable elegance, they remain in its thrall. Haacke’s objectified comments on 1980s commodity art are fitting epitaphs for such an art of the instrumentalized readymade, and his body of work as a whole can be seen as a sustained attempt to think through the readymade’s limitations as well as its consequences.

Hans Haacke, Broken R.M., 1986

In the 1920s, both Lukács in History and Class Consciousness and, slightly later, Heidegger in Being and Time, critiqued the subject-object dichotomy in modern philosophy.1 Both authors attempted to develop an analysis of the complex situatedness of praxis in the world, but in Heidegger’s case this praxis was a depoliticized and dehistoricized Sorge, a taking-care of being along the lines of the earth-bound farmer taking care of the Scholle (the earth shoal, a favorite term in reactionary and Nazi philosophy during the 1920s and 1930s). Heidegger recalled that the term Ding originally referred to a form of archaic assembly, and in recent years Bruno Latour has latched onto this genealogy to redefine things in terms of “matters of concern” rather than “matters of fact,” as quasi-objects and quasi-subjects that fall between the two poles of the dichotomy.2 As I have argued—contra Latour—this needs to be seen as a critical project within modernity that brings together thinkers and artists (and not only them, obviously) that would be bien étonnés de se trouver ensemble.

Haim Steinbach, Ultra Red No.1, 1986.

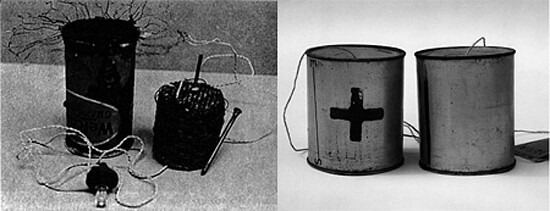

Last year, in an exhibition that was part of a series of events on “social design,” curator Claudia Banz combined elements from the publications of Victor Papanek with a selection of multiples by Joseph Beuys.3 Bringing together Papanek’s designs for cheap and low-tech radios and televisions for use in third-world countries with works such as Beuys’s Capri Batterie (1985) and Das Wirtschaftswert-PRINZIP (1981), the exhibition subtly shifted the perception of Beuys’s works in particular. The works were displayed in the usual way, in display cases that tend to turn them into relics; yet the proximity of the radio and TV designs brought out aspects of these things that often remain dormant. Yes, the appropriated East German package of beans with its non-design has become a meta- and mega-fetish like so many other readymades, yet the constellation in which it has been placed opens up new connections, a new network of meaning. The Capri Batterie, like the 1974 Telephon S-E made from tin cans and wires, may be tied up with mystifying anthroposophical conceptions of energy and communication, but this combination emphasizes that it would be a mistake to see such Beuysian things purely as expressions of a private mythology. In a different field and in a different register from Papanek’s work, they too are counter-commodities—and while it would be a mistake to lose sight of their compromised status, it would be an even bigger one to be content with that observation.

From left: illustration in Victor Papanek, Design for the Real World. 2nd edition, p. 225; Joseph Beuys, Telephon S-E, 1974, Courtesy Edition Schellmann, München-New York © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2008.

Even if we were to disregard Beuys as regressive and unmodern, many of the 1960s and 1970s practices that are most steeped in the tradition of critical theory that Latour seeks to toss into the dustbin of history show that a critique of commodification is something rather different from a “ceaseless, even maniacal purification.” Martha Rosler’s various versions of her Garage Sale piece involve her mimicking this American suburban version of the Surrealists’s flea market; having been advertised in art and non-art media, it is a more or less normal garage sale to some, and a performance to others. However, Rosler noted that the setting transformed even the art crowd into a posse of bargain hunters, who did not pay that much attention to the structure of the space, with odd and personal objects tucked away in the outer corners, or to the slide show and sound elements. For a 1977 version, Rosler assumed the persona of a Southern Californian mother with “roots in the counterculture,” who on an audiotape that played in the place mused on the value and function of things: “What is the value of a thing? What makes me want it? … I paid money for these things—is there a chance to recuperate some of my investment by selling them to you? … Why not give it all away?” The woman goes on to quote Marx on commodity fetishism and to wonder if “you [will] judge me by the things I’m selling.”4

In such a work, the object is placed in a network that is social and political, not merely one of signs. Semiosis is always a social and political process. There is a diagrammatic dimension to such a piece, as there is, in different ways, to many works of Allan Sekula or Hans Haacke. If the diagram in Rosler’s piece is one that primarily concerns the circulation of objects in suburban family life, a number of Haacke’s works contrast the use of corporations’s logos in the context of art spaces, where they become disembodied signs, with those corporations’s exploitation of labor or involvement in authoritarian or racist regimes; Sekula’s Fish Story and related projects chart the largely unseen trajectories of commodities and workers on and near the oceans. Things and people. These practices, in particular those of Haacke and Rosler, spring from a critical reading of both the Duchampian heritage and the Constructivist project, which was being excavated in the same period by art historians, critics, activists, and artists. In their reading of these two genealogies, these artists recover some of the impetus behind the Constructivist/Productivist attempt to redefine the thing.

Sean Snyder,Index, 2009, installation view at ICA, London. Photo: Marcus J. Leith.

A diagrammatic impulse, an attempt to trace the trajectories of people and things, can also be seen in recent work such as Sean Snyder’s Untitled (Archive Iraq) (2003–2005) and related pieces, tracking the circulation of various types of commodity in the contested terrains of Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. When Snyder, in his photo pieces and films, zooms in on Fanta cans or Mars bars, on Casio watches or Sony cameras, the “social relations” between these commodities are not limited to the fetishistic coded differences celebrated by commodity art.

Filmic montage can be one tool for keeping track of things, of comparing different modes of production and distribution. In this respect, Allan Sekula’s films and Harun Farocki’s installation Vergleich über ein Drittes (Comparison via a Third) (2007) are strong demonstrations of the possibilities of filmic means—and in Farocki’s case, of their use in multi-channel video installations. A diagrammatic impulse can also be discerned in such filmic pieces; but here, as in the case of Snyder’s Untitled (Archive Iraq), the aim is not to strive for some suggestion of complete transparency that would reduce objects to geometric points for a sovereign subject to grasp at a glance. Rather, the objects and subjects are placed in a jumbled constellation in which they become problematic, questionable things and people. Of course, the artificial limitations on the availability of film and video pieces in the contemporary art economy make such pieces highly questionable things in their own right, and crucial projects such as Snyder’s Index, which involves the digitization and uploading of the artist’s archive, address the limitations of the dominant form of media objecthood.

Harun Farocki, Comparison Via a Third [Vergleich über ein Drittes],2007, 16 mm film, color, sound, 24min.

The limitations imposed on the circulation of commodities by intellectual property law are also scrutinized in a number of projects by Superflex—commodities that include, in their current project at the Van Abbemuseum, a wall piece by Sol LeWitt. In a less interventionist and (in the military sense of the term) offensive way than Superflex, Agency/Kobe Matthys charts the legal battles waged over the use of objects, images, and programs by collecting, investigating, and exhibiting specific things. A recent installation in Anselm Franke’s “Animism” exhibition at Extra City in Antwerp contained a number of things that have been subject to litigation, as instances in which human authorship is thrown into question because of the role played by the non-human (technological, animal), with items ranging from bingo cards to a video game and a German TV broadcast of a circus act with elephants. Exhibited in a space lined with crates containing many more items, the space seemed to channel Surrealism via Mark Dion. Some of the things on display had an anachronistic quaintness to them, yet Matthys’ classified readymades go beyond the conventional exacerbation of the commodity’s theological (or animist) whims.

There are, of course, other important examples of practices that seek to push the work of art to a point where it reveals itself to be a special category of thing that reflects (on) the state of things. Here one may think of Michael Cataloi and Nils Norman’s “University of Trash” project, with its investigation into various alternative economies and social structures proposed in the 1960s and 1970s, and of Ashley Hunt and Taisha Paggett’s project about the garment industry and its workers, with its charting of the movements of contemporary products across the globe. Some of these projects and practices may be more successful than others, but an important characteristic that they share is that their embrace of the work of art’s “thingified” status is not a capitulation, an assimilation of the work of art to the dreaded world of hat racks and other arbitrary objects. Rather, such projects are interventions into our society’s production of (in)visibility. If anything, they can more properly lay claim to continuing the project of modern aesthetics than those intent on erecting a wall around the work of art; after all, from Schiller and the Jena Romantics onwards, the modern aesthetic project was expansive, aimed at intervening in the “art of living.”5

However, avant-garde attempts to abandon autonomous art in favor of a complete integration of art and life were as misjudged by critics as modernist rappels à l’ordre that limited art to reflecting on the unique properties of its mediums, or later attempts to limit Conceptual art to a series of proposals about its own status as art and nothing else.6 Even Constructivist forays into production in the early 1920s depended on a specialist sphere of practice and discourse whose confines they sought to escape—a sphere that would soon be destroyed by Stalin. On the other hand, a properly reflexive work of art can never be only about its status as art, about “art itself.” Since art’s apparent autonomy is socially conditioned, the obverse of its heteronomous inscription in a global capitalist economy that penetrates into ever more realms of life and parts of the planet, the work of art’s self-reflection is a sham it if is not potentially about everything, and every thing.

Georg Lukács, preface to History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics (1923), trans. Rodney Livingstone (London: Merlin Press, 1971), xxii. Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, trans. Joan Stambaugh (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 59.

Bruno Latour, “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik or How to Make Things Public,” in Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, eds. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (Karlsruhe/Cambridge, MA/London: ZKM/MIT Press, 2005), 23.

“Design for The Real World,” Centraal Museum Utrecht, October 4, 2009 – February 7, 2010 (part of Utrecht Manifest 2009, Biennial for Social Design). The designs in question are illustrated in Victor Papanek, Design for the Real World, 2nd ed. (London: Thames & Hudson, 1985), 81–83, 225–226.

Martha Rosler, “Traveling Garage Sale” (1977), in Martha Rosler: Positions in the Life World, ed. Catherine de Zegher (Cambridge MA/London: MIT Press, 1998, unpaginated section.

See Jacques Rancière, “The Aesthetic Revolution and Its Outcomes,” in New Left Review 14 (March–April 2002), →. Rancière’s writings on the modern “aesthetic regime of art” have become almost suspiciously popular in the art world; when Rancière writes that “Aesthetic art promises a political accomplishment that it cannot satisfy, and thrives on that ambiguity,” this seems to generate a pleasant vagueness, legitimizing anything and everything. However, one could and should in fact see it as an incentive to examine possible correspondences and points of connection, however fraught with difficulty, between art and different (especially political) interventions in the sensible realm.

Writing about the conceptual essay-as-a-work-of-art, Jeff Wall argues that it can only be about its own status as an artistic kropsla; it can’t be about any other subject. Jeff Wall, “Introduction: Partially Reflective Mirror Writing,” in Two-Way Mirror Power: Selected Writings by Dan Graham on His Art, ed. Alexander Alberro (Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press, 1999), xv.