The Christian era was heralded by a bright star over Bethlehem. The age of global capitalism, not to be outdone, was ushered in by not one but two celestial phenomena appearing in the night sky in 1572 and 1604. With little fanfare beyond scientific circles, these astronomical events consolidated a new secular orientation that would ultimately eclipse the world that had been exhaustively described by Aristotle. They did not involve stars per se, but rather supernovas: massive stars that spectacularly explode after running out of material to fuse.1 If we now attribute these superlunary events to events on earth, it is because we know what was happening at the time in the small world of Dutch commerce.

The two explosions are named after astronomers who helped launch the scientific revolution, Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler—a Dane who collected observations and a German who interpreted these observations, respectively.2 Supernovas were already known as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) by Chinese astronomers, who called such events “guest stars” (客星, kèxīng). The years 1572 and 1604 are significant not so much for what was happening in the sky as for what was taking place on the ground in the small, newly instituted Dutch Republic. A conjunction had occurred between the market, originally confined to the city, and the territory of the state.3 This transition was not predestined, and resulted from a set of terrestrial events that were not spontaneous.4 Changes in monarchical power, wars, vacillations in religious doctrines and edicts, all occurred a few years after Tycho’s supernova and led to the formation of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands in 1579.

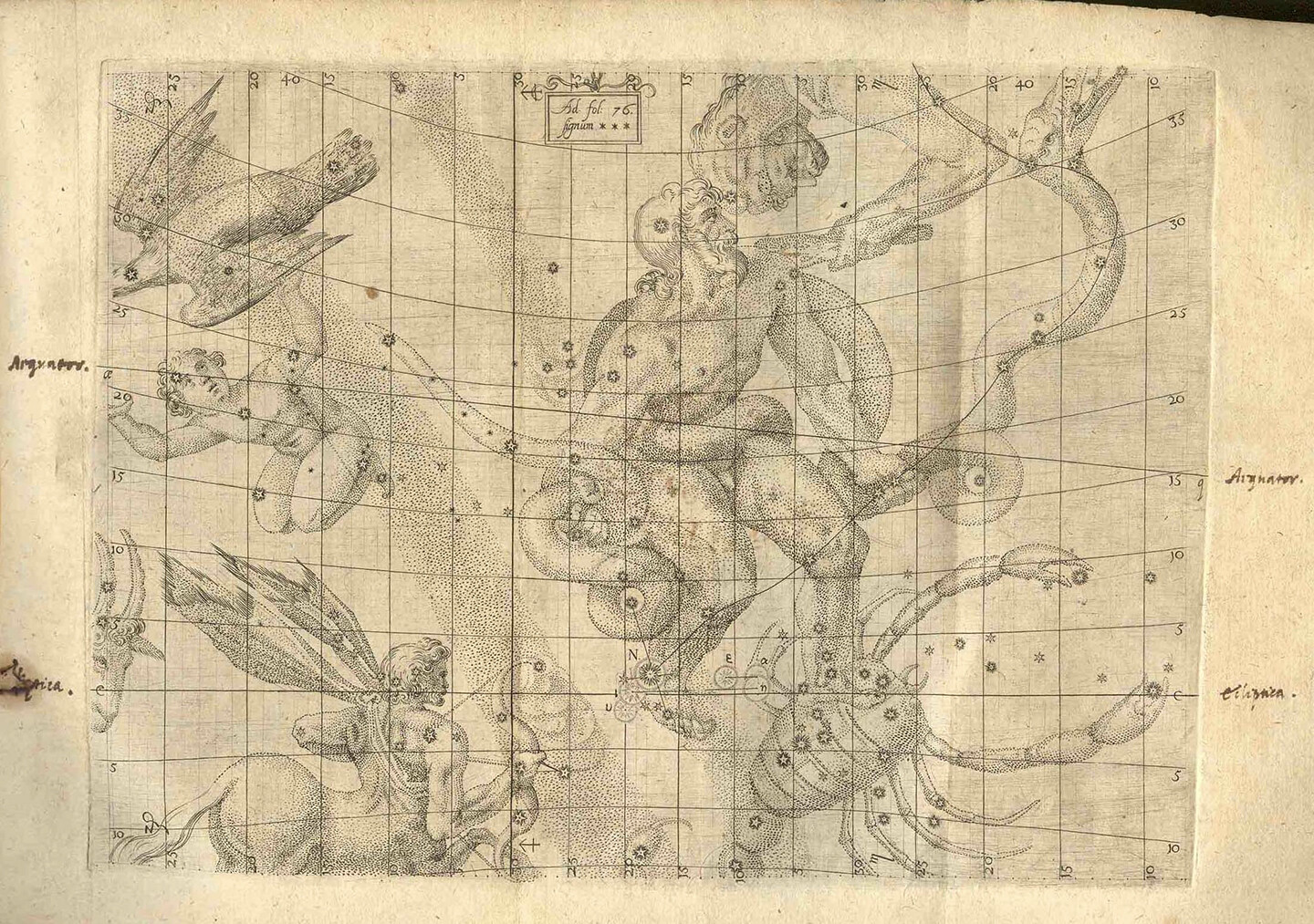

Tycho Brahe’s mural quadrant in Uranienborg (Uraniborg). The quadrant (radius c. 194 cm) was made from brass and was affixed to a wall that was oriented precisely north-south. The observer (far right) views a star through the opposite opening (upper left) to determine the star’s altitude as it passes through the meridian. An assistant (lower right) reads the time off a clock and another one (lower left) records the measurements. The area above the quadrant is filled with a mural painting showing several other of Brahe’s instruments. License: Public domain.

The key difference between the city markets of antiquity and the state-backed market inaugurated by the Dutch is the simple fact, explained by the American physicist P. W. Anderson in 1972, that “more is different.” A statewide commitment to capital accumulation transforms a market into an empire, but in such a way that merchants no longer serve the court, but the other way around. Under the rule of merchants, long-established forms of business exchange, such as the government securities established by Venetian bankers in the thirteenth century, expand to a historically significant scale. The Dutch Golden Age began a rapid movement towards the universalization of capital that Marx and Engels would valorize in The Communist Manifesto.

Instead of prognosticating, simply looking at stars and recording their movements ultimately broke the ancient power of Aristotelian metaphysics because the obsessions of merchants—shipping logistics, quality control, balance of payments—were, unlike those of churchmen, practical and concerned with the world as it is experienced by the senses: cause and effect. It was called “natural philosophy” in the days of Dutch capital accumulation, but today’s name for this kind of knowledge is “science.” The Enlightenment was a byproduct of this emphasis on what is practical, on this revolutionary mode of interpreting physical phenomena. It was only accidental that the instrument devised to check the quality of cloth, the microscope, revealed the invisible world of microorganisms.5 But it wasn’t accidental that the first major achievements of these new philosophers—one of whom was, of course, Dutch—involved transforming the entire universe into a machine.6 And this machine conception has never left us: there is classical mechanics (Newton), statistical mechanics (Boltzmann), and quantum mechanics (Bohr). Capital can only exist in a machine.

Just as “a fool and his money are soon parted,” so merchants, the first capitalists, must reduce their risks with reliable equipment, accurate accounting, maps, and weapons to overcome obstacles to their return on investment. For this, the Dutch had technical assurances, some originating from the Islamic world, with much of the innovation in optics that characterized the Dutch Golden Age having been theorized at the end of the first century by the scholar and mathematician Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham.

The formation of a market economy (merchants as masters) widens and expresses something not new—capital—in a very new way. With the supernovas, academic knowledge divorces the church and marries capital. And this new union, this encompassing fate for the world, was not written in the stars (or spontaneous). It’s conceivable that after 1579, a thousand more years might have passed without a break from Aristotle. Civilizations might have risen without any concession to the market economy. West African drumming might have continued its dominance over long-distance communication.7

It was the second supernova that sealed the deal for the emergence and expansion of the universal market. Giambattista Vico, Adam Smith,8 Hegel,9 and ultimately Marx10 confused this specific form of universal history with the transhistorical history of “mankind.”

The debate about how capitalism began is long and dreary, and it roughly looks like this: For world systems thinkers such as the late Giovanni Arrighi, it began in fifteenth-century Italy with the city market. According to this view, the period saw a movement from productive capitalism to financial capitalism, a shift that world-systems thinking identifies in all leading capitalist societies: the Italian city states (particularly Genoa11), the Dutch, the British, the Americans, and presently China.12 You begin with goods and you end with paper. Ellen Meiksins Wood, a key figure of political Marxism, dismissed Dutch imperialism as a starting point and instead located the birth of capitalism in rural Great Britain—a description challenged by the expansion of capital from the limits of the city to the scale of the state, eliminating the city-rural distinction that so bothered Raymond Williams in his influential 1973 book, The Country and the City. In fact, one only has to look at Jacob van Ruisdael’s painting View of Haarlem with Bleaching Fields to see country and city as a unified field of capital accumulation in the seventeenth century.13

Jacob van Ruisdael, View of Haarlem with Bleaching Grounds, circa 1665. License: Public domain.

Maurice Dobb and Paul Sweezy famously debated the point of transition from feudal economy to market economy.14 Though I side, in part, with Dobb’s position, I also side with Wood’s political Marxism, which, like the Neue Marx-Lektüre inaugurated by Adorno’s return to postwar Germany, emphasized the historical specificity of capitalism. But what’s needed in these and other attempts to determine the origins of a culture that’s become truly universal is the recognition of a unique temporality, one that moves, as with entropy, in one direction only, which appears to us as forward.15 The experience of this direction, from which there is no going back, is made sensible by technological advancements actualized by the scientific accumulation of knowledge.

Capitalism is not cyclical but progressive. And so we, the present subjects of this system, the stuff of exploded stars (in both the physical and cultural sense), are in the same temporality as Hegel at the beginning of the nineteenth century: stadial temporality. The Geist of the German philosopher can be none other than the spirit of capitalism.16 Hegel confused this temporality with the universal temporality of our system of commercial exchanges.17 His Geist is spontaneous. To identify the supernovas with the origins of capital accumulation can only render impossible Hegel’s spiritual teleology.18 And this understanding liberates us from capitalist spontaneity completely, from saying Victorian-sounding things like “human anatomy contains a key to the anatomy of the ape.” Despite their sophisticated theoretical apparatus, what Marx and Engels couldn’t see in capitalism’s historical specificity is that the chimpanzee is, after all, as evolved as we are. We can blame this bad thinking on the fact that they couldn’t see capitalism as accidental, as a culture that might easily not have been. The supernovas make apparent this accident.

But what follows? Must it be disenchantment? When the merchants attach science to capital accumulation, the entire world is gripped by number, calculation, precision.19 Everything has to be accounted for. Time and space must be measured. This determination is captured in capital’s first artworks, the paintings of the Dutch Golden Age. The disenchantment of the era is made apparent in the stark church paintings of Pieter Saenredam: the absence of decoration, the sobriety of walls and windows, the businessmen gathered in a corner to conclude some matter related to the stock market. There is also the emphasis on exactness, on detail, on cataloging. Insects appear in paintings, which is truly astonishing. The Italian tradition hardly saw any animals other than humans (which were often angels), let alone bugs. But they are everywhere in Dutch art, buzzing around food (fish, wine, bread, the wilting flowers of Clara Peeters). Indeed, the art historian Svetlana Alpers argued that in capital’s formative period, the line between the telescope and microscope did not exist. The painter becomes an instrument:

One is struck by the almost indiscriminate breadth of Leeuwenhoek’s attentiveness—he turns his microscope on his sputum, feces, and even his semen as easily as he did on the flowers of the field. Leeuwenhoek combines absorption in what is seen with a selflessness or anonymity that is also characteristic of the Dutch artist. Indeed, the conditions of visibility that Leeuwenhoek required in order to see better with his instruments resemble the arrangements made by artists. He brings his object, fixed on a holder, into focus beyond the lens. He adjusts the light and the setting as the artists were to do. To make the object of sight visible—in one case globules of blood—Leeuwenhoek arranges the light and background (in a way that is still not completely understood) so that the globules will, in his words, stand out like sand grains on a piece of black taffeta. It is as if Leeuwenhoek had in mind the dark ground favored by Dutch still-life painters.20

Jan Verkolje , Portrait of Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), circa 1680. Rijksmuseum. License: Public domain.

But this kind of sobriety is well known. It’s announced in The Communist Manifesto. We are told there that “the bourgeoisie” has through “callous ‘cash payment’” drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervor … in the icy water of ‘egotistical calculation.’”21 We hear it again and again. “Cash [Calculation] Rules Everything Around Me.”22 And we are impressed, again and again, by its apparent facticity.23 The disenchantment side of capitalism is not, however, as interesting as its re-enchantment side. Indeed, the latter, despite being almost ignored or confused with Marx’s concept of fetishizing commodities (a spell that’s broken by examining the “hidden abode of production”), can be even more important than the former. And here we reach the main point of this essay: capital does not do away with enchantment’s “structures of feeling,” but relocates and reinvests them in a way that makes its cultural mode distinct from all other cultural modes.24

How can we confirm that the Dutch made the first complete transition to a culture we can identify as capitalist? Though its size and extent is still debated by historians, the “tulip mania” of 1634 was the mother of all bubbles. Its cultural embeddedness is attested to by the fact that trading took place in taverns rather than in the stock market.25 There are features of the mania that capture capitalist re-enchantment. It must be recalled that, while the flower originating in Central Asia was initially of scientific interest to the Dutch, it soon gained the same luxury status it had in the Islamic world. Indeed, the key to capitalist products is not their use value but their uselessness, which is why so many goods driving capitalist growth were (and are) luxuries: coffee, tea, tobacco, beef, china, spices, chocolate, single-family homes, and ultimately automobiles—which define capitalism in its American moment. It’s no accident that the richest man of our times is a car manufacturer.26

The story of how the tulip fueled an inflationary bubble that began in 1634 and reached its peak in the first months of 1637 has all the features of bubbles that have appeared ever since. Trading in the commodity quickly transitioned from the object itself (bulbs) to sheets of paper, facilitated by a very mature futures market. It then became a matter of making sure that one had a chair when the music stopped, mainly by pushing dodgy paper over to a sucker.

But capital’s re-enchantment is best captured by the flower itself. Like coffee, tea, and tobacco, it is utterly useless in terms of nutrition or medicine. Moreover, at the time the most prized flowers suffered from a viral infection that increased their color variegation. In fact, one of the most popular tales of the tulip mania bubble involves a sailor who mistakenly thought tulip bulbs were useful:

A wealthy merchant, who prided himself not a little on his rare tulips, received upon one occasion a very valuable consignment of merchandise from the Levant. Intelligence of its arrival was brought him by a sailor, who presented himself for that purpose at the counting-house, among bales of goods of every description. The merchant, to reward him for his news, munificently made him a present of a fine red herring for his breakfast. The sailor had, it appears, a great partiality for onions, and seeing a bulb very like an onion lying upon the counter of this liberal trader, and thinking it, no doubt, very much out of its place among silks and velvets, he slily seized an opportunity and slipped it into his pocket, as a relish for his herring. He got clear off with his prize, and proceeded to the quay to eat his breakfast. Hardly was his back turned when the merchant missed his valuable Semper Augustus, worth three thousand florins … The whole establishment was instantly in an uproar; search was everywhere made for the precious root, but it was not to be found. Great was the merchant’s distress of mind. The search was renewed, but again without success. At last someone thought of the sailor. The unhappy merchant sprang into the street at the bare suggestion. His alarmed household followed him. The sailor, simple soul!, had not thought of concealment. He was found quietly sitting on a coil of ropes, masticating the last morsel of his “onion.” Little did he dream that he had been eating a breakfast whose cost might have regaled a whole ship’s crew for a twelvemonth.27

The sailor was, according to the story, sent to prison for “months on a charge of felony preferred against him by the merchant.” Though likely a tall tale, it nevertheless goes to the heart of capitalist re-enchantment: use value (onion) is nothing compared to exchange value (tulip bulb). What makes an onion useless is precisely that it is socially, biologically useful. Capitalism has never been about use value at all, a misreading that entered the heart of Marxism through Adam Smith’s influence on Marx’s political economy. 28 The Dutch philosopher Bernard Mandeville’s economics, on the other hand, represents a reading of capitalism that corresponds with what I call its configuration space, in which the defining consumer products are culturally actualized compossibilities—and predetermined, like luxuries associated with vice. The reason is simple: capitalism would simply die if it met all of our needs, and our needs are not that hard to fill.

This is precisely where John Maynard Keynes made a major mistake in his remarkable and entertaining 1930 essay “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.”29 He assumed that capitalism’s noble project was to alleviate its own scarcity, its own uneven distribution of capital. Yes, he really thought that the objective of capitalism was capitalism’s own death.30 And indeed, the late nineteenth-century neoclassical economists universally believed this to be the case. They told the poor to leave capital accumulation to the specialists, as it alone could eventually eliminate all wants and satisfy all needs.31 It’s just a question of time.32 It is time that justified the concentration of capital in a few hands, the hands of those who had it and did not blow it. And this fortitude, which the poor lacked, deserved a reward. The people provided labor, which deserved a wage; the rich provided waiting, which deserved a profit. This idea was pushed in an economic textbook by John Maynard Keynes’s teacher, Alfred Marshall.33

What was missing in Keynes’s utopia? 34 Even with little distinction from socialism, what was missing was the basic understanding that capitalism is not about producing the necessities of life, but about using every opportunity to transfer luxuries from the elites to the masses. This is the point of Boots Riley’s masterpiece Sorry to Bother You (2018), a film that may be called surreal by those who have no idea of the kind of culture they are in. The real is precisely the enchantment, the dream. Capitalism’s poor do not live in the woods but instead, like Sorry to Bother You’s main character, Cassius “Cash” Green (played by LaKeith Stanfield), drive beat-up or heavily indebted cars; work, in the words of the late anarchist anthropologist David Graeber, “bullshit jobs”; and sleep in vehicles made for recreation (RVs) or tents made for quick weekend breaks from urban stress, or for the lucky ones, in garages (houses for cars). This is what poverty actually looks like in a society that’s devoted to luxuries rather than necessities. Cultural theorist Noam Yuran writes:

As an example of the orthodox concept of the economy, we can [turn] to Keynes’s paper “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.” Almost a century after the writing of this essay, we cannot avoid the question of how this great thinker was so naive as to believe that in our time humanity would have freed itself from the problem of scarcity. An answer can be found in the paper itself. Keynes distinguishes between two types of needs: absolute needs, which are unrelated to the situation of our fellow human beings, and relative needs, which drive us to feel superior to our fellows. Keynes acknowledges the fact that the latter type of needs, in contrast to the former, has no theoretical possibility of satisfaction. Yet, he claims that with reference to absolute needs “a point may soon be reached … when these needs are satisfied in the sense that we prefer to devote our further energies to non-economic purposes.” This conclusion rests on the commonsensical idea that absolute needs are prior to relative needs. That is to say, people toil to have what they absolutely need and, once they have it, may try to have more than others (but being rational, they will tend to give up on this goal). In other words, Keynes’s prediction rests on the idea that having is logically prior to having more.35

Yuran is getting at something very powerful. Capitalism is not, at the end of the day, based on the production of things we really need (absolute needs), for if it was, it would have already become a thing of the past. Or, in the language of thermodynamics, it would have reached equilibrium. (Indeed, the nineteenth-century British political economist John Stuart Mill called this equilibrium “a stationary state.”36)

For example, an apparent shortage of housing—an absolute need or demand, meaning every human needs to be housed—could easily be solved. But what do you find everywhere in a very rich city like Seattle? No developments that come close to satisfying widespread demand for housing as an absolute need. This fact should sound an alarm in your head. We are in a system geared for relative needs. And capital’s re-enchantment is so complete that it’s hard to find a theorist who has attempted to adequately (or systemically) recognize it as such. This kind of political economy (or even anti-political economy) would find its reflection in lucid dreaming. Revolution, then, is not the end of enchantment (“the desert of the real”) but can only be re-enchantment. We are all made of dreams.

LaKeith Stanfield in Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You, 2018. Annapurna Pictures.

Boots Riley is a lucid dreamer, which is why his political economy is closer to reality than anything you find in the neoclassical school’s rational man, rational markets, rational outcomes. The same goes for Noam Yuran and the Jean Baudrillard of his neglected post-Marxist masterpiece The Mirror of Production. What young Baudrillard grasped, and what communists, socialists, and Keynesians missed, is that the manufactured (“Main Street”) products of capitalism are as fantastic as the financial fabrications of Wall Street.37 A tulip, a collateralized debt obligation (the famous CDOs of the financial crash of 2007), have as much use value as America’s best-selling pickup truck, the Ford F-150. They are all “ectoplasms.”38

The supernovas that opened the gates of capitalist dreamtime reappeared during the end of the world’s first bubble.39 In Tulipomania, Mike Dash writes: “By the beginning of February, money and bulbs—the twin fuels of the flower mania—were both exhausted. And like a sun that has burned the last of its fuel, the tulip mania ‘went supernova’ in a final, frenzied burst of trading before collapsing in on itself.”40

“A supernova produces a burst of light billions of times brighter than the Sun, reaching that brightness just a few days after the start of the outburst. The total amount of electromagnetic energy radiated by a supernova during the few months it takes to brighten and fade away is roughly the same, as the Sun will radiate during its entire ten-billion-year lifetime.” W. Shea, “Galileo and the Supernova of 1604,” in 1604–2004: Supernovae as Cosmological Lighthouses, ASP Conference Series, vol. 342 (2005): 13 →.

“Galileo did not hear about the supernova for several days, and his first recorded observation is dated 28 October. By then the news had become a sensation, and everyone wanted to know what the professor of Astronomy at the University of Padua had to say about it. Galileo had held that position since 1592, but this was the first time in twelve years that he was called upon to give a public lecture. The subject was so hot that he gave not one, but three lectures. Only the first page and a fragment of the end of his first lecture have survived, and we do not know exactly when he delivered these talks, but it was probably during November while the star could still be seen in the evening sky. From the last week in November until after Christmas, it was too near the Sun to be visible. When it reappeared it could be seen just before dawn in the East.” W. Shea, “Galileo and the Supernova of 1604,” 15.

The last major stateless market city was Antwerp, which was sacked in 1576.

I use “spontaneous” in its thermodynamic sense, as a natural tendency. There is nothing spontaneous about capitalism.

Much to the disappointment of Leibniz, the Dutch cloth merchant Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) treated the microscope not as a scientific object but as a secret asset an enterprise can use to maintain what Marx called “relative surplus value.”

Christiaan Huygens (1629–94) is credited with determining the connection between mass and velocity. This resulted in one of the most famous equations of the first mechanical age: F = mv²/R.

James Gleick writes that the African talking drum “was a technology much sought in Europe: long-distance communication faster than any traveler on foot or horseback. Through the still night air over a river, the thump of the drum could carry six or seven miles. Relayed from village to village, messages could rumble a hundred miles or more in a matter of an hour.” The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood (Pantheon, 2011).

Ronald L. Meek writes: “This line of inquiry, says Stewart, began with Montesquieu, who ‘attempted to account, from the changes in the condition of mankind, which take place in the different stages of their progress, for the corresponding alterations which their institutions undergo.’ As a description of Montesquieu’s approach this is a little inept: few clear traces of a stadial view of this type can in fact be found in the Spirit of Laws. As a description of Smith’s approach, however, it is very accurate indeed.” But the stadial theory of human development begins with Francis Hutchenson, the father of the Scottish Enlightenment, which might be more important than the French Enlightenment (referred to as “the Enlightenment”). Smith, Marx & After: Ten Essays in the Development of Economic Thought (Chapman & Hall, 1977), 21.

Though György Lukács’s masterful The Young Hegel substantially describes Adam Smith’s impact on Hegel, he doesn’t connect Smith’s stadial theory of history with Hegel’s theory of history progressing, as Geist (Spirit), from lower to higher stages. Hegel’s Spirit might very well be a combination of Spinoza’s unmoving substance (“the oriental conception of emanation as the absolute is the light which illumines itself” but doesn’t reflect) and the motive force of the stadial theory elaborated by the Scottish Enlightenment.

Though Marx did emphasize the cultural specificity of capitalism, particularly in Grundrisse and Capital volume one, he never really broke with the stadial view of history, made clear by his late and unproductive statement that “human anatomy contains a key to the anatomy of the ape.”

Giovanni Arrighi writes: “It so happens that Braudel’s notion of financial expansions as closing phases of major capitalist developments has enabled me to break down the entire lifetime of the capitalist world system (Braudel’s longue durée) into more manageable units of analysis, which I have called systemic cycles of accumulation. Although I have named these cycles after particular components of the system (Genoa, Holland, Britain, and the United States), the cycles themselves refer to the system as a whole and not to its components.” The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times (Verso, 1994), xiii.

Giovanni Arrighi includes China in the list of capital’s dominant accumulation cycles in his final book, Adam Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the Twenty-First Century (Verso, 2007).

The steam engine also played an important role in concentrating capital in cities. The machine was, unlike rivers, portable.

Ellen Meiksins Wood, who provides an excellent summary or the long and as yet unresolved “transition debate” in The Origin of Capital: A Longer View (Verso, 2002), writes: “The central question at issue between Sweezy and Dobb was where to locate the ‘prime mover’ in the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Was the primary cause of the transition to be found within the basic, constitutive relations of feudalism, the relations between lords and peasants? Or was it external to those relations, located particularly in the expansion of trade?” p. 38.

Does a cultural system see what it wants to or can believe? I ask this question because it’s curious that entropy, which now plays the role of the leading description of the motion of the whole universe, was discovered by engineers and scientists seeking to improve the efficiency of the steam engine.

Helmut Reichelt: “In Marx’s thought the expansion of the concept into the absolute is the adequate expression of a reality where this event is happening in an analogous manner … Hegelian idealism, for which human beings obey a despotic notion, is indeed more adequate to this inverted world than any nominalistic theory wishing to accept the universal as something subjectively conceptual. It is bourgeois society as ontology.” Helmut Reichelt, Zur logischen Struktur des Kapitalsbegrifs bei Marx (ça ira-Verlag, 2001), 76–77, 80. Translated by Riccardo Bellofiore and Tommaso Redolfi Riva as “The Neue Marx-Lektüre: Putting the Critique of Political Economy Back into the Critique of Society,” Radical Philosophy, no. 189 (January–February 2015).

Moishe Postone writes that Marx “explicitly characterizes capital as the self-moving substance which is Subject. In so doing, Marx suggests that a historical Subject in the Hegelian sense does indeed exist in capitalism, yet he does not identify it with any social grouping, such as the proletariat, or with humanity. Rather, Marx analyzes it in terms of the structure of social relations constituted by forms of objectifying practice and grasped by the category of capital (and, hence, value). His analysis suggests that the social relations that characterize capitalism are of a very peculiar sort—they possess the attributes that Hegel accorded the Geist. It is in this sense, then, that a historical Subject as conceived by Hegel exists in capitalism.” Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Following the Neue Marx-Lektüre and Moishe Postone, the young Marxist scholar Søren Mau writes: “The resemblance between capital and the subject in this Hegelian sense comes out very clearly in Marx’s analysis of capital. For him, capital is fundamentally a movement, or ‘value-in-process.’ The beginning and the end of this movement are qualitatively identical: with capital, value ‘enters into a private relationship with itself,’ thereby elevating its being-for-others—that is, being-for-consumption in the case of simple circulation (C-M-C)—to ‘being-for-itself.’” Mute Compulsions (Verso, 2024).

The most rewarding chapter in James Joyce’s Ulysses, “Ithaca,” moves between the cosmic and the commercial with great ease. The two cannot be separated. Measuring economic activity and the distance to stars are directly related. The accounting intensity (or mania) of the former made the latter inevitable. How much did you spend today? How bright is the moon tonight? How long does it take for a ship to cross the ocean? How long does it take for light to arrive from that galaxy? What are the assets in your mother’s will? What is the composition of water? “Ithaca” is the stuff of a disenchanted society.

Svetlana Alpers, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the 17th Century (University of Chicago Press, 1984), 83. In the way Alpers’s book was inspired by Foucault’s The Order of Things, this essay is inspired by Roland Barthes’s brilliant but too-brief “The World as Object.” Barthes’s reading of Dutch Art: “The Dutch scenes require a gradual and complete reading; we must begin at one edge and finish at the other, audit the painting like an accountant, not forgetting this corner, that margin, that background, in which is inscribed yet another perfectly rendered object adding its unit to this patient weighing of property or of merchandise.” Critical Essays (Northwestern University Press, 1972), 7.

We know this line in the same way we know Jimi Hendrix’s “Star Spangled Banner.” It’s not an accident that Raoul Peck’s The Young Karl Marx ends with a classic tune by Bob Dylan.

Wu-Tang Clan, “C.R.E.A.M.,” Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) (Loud Records, 1994).

Marx writes in Capital volume one: “In the midst of all the accidental and ever fluctuating exchange relations between the products, the labour time socially necessary for their production forcibly asserts itself like an overriding law of Nature. The law of gravity thus asserts itself when a house falls about our ears” →. I must here point out that what Marx calls “socially necessary,” I call “culturally necessary.” The social is transhistorical; the cultural is not. A society is the object investigated by sociobiology; a culture is the subject of anthropology. The productions of the former are spontaneous; those of the latter are not.

I transport this concept coined by Raymond Williams in 1954 to the post-Althusserian structuralism spelled out in Stuart Hall’s 1973 lecture “A ‘Reading’ of Marx’s 1857 Introduction to the Grundrisse” (Centre for Cultural Studies, University of Birmingham). Personal feelings are structured by the culture one is in. In our case, that culture is capitalism. It must also be noted that Hall’s Althusserian point of departure has greater explanatory power than Foucault’s.

The oldest known book about the stock market is Joseph Penso de la Vega’s Confusión de Confusiones, which was published in the twilight of the Dutch Golden Age (1688) and presents the speculative mania in way not so different from how films like Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Eclisse (1962) and Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987) depict it.

Not long after Donald Trump was reelected on November 5, 2024, Bloomberg reported that Elon Musk’s market value exploded from $200 billion to over $400 billion →.

Charles Mackey, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841). The description of tulip mania is not as competent as the book’s description of the “Mississippi Scheme” that gave us the expression “bubble.”

However, one thing that can said about Adam Smith’s sprawling survey of commercial society is that all the defining positions of the leading schools of economics, from Marxism to modern monetary theory, can be found, in some form or another, expressed in it. For example, Smith is aware that capitalism is not about needs but desires. This fact is captured in the famous diamond-water paradox. Smith writes in Wealth of Nations: “The things which have the greatest value in use have frequently little or no value in exchange; on the contrary, those which have the greatest value in exchange have frequently little or no value in use. Nothing is more useful than water: but it will purchase scarcely anything; scarcely anything can be had in exchange for it. A diamond, on the contrary, has scarcely any use-value; but a very great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it.” “Of the Origin and Use of Money,” in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776. This is only a paradox if you refuse to recognize capitalism’s reenchantment. Tulips and diamonds, property values and AI—what matters is not what you can eat, but what melts into air.

John Maynard Keynes, Essays in Persuasion (W.W. Norton & Co., 1963), 358–73.

Marx thought capital produced its own gravediggers, the workers. Keynes believed capital was its own gravedigger. It could dig its own grave by becoming too abundant. In the latter case, the Sweezy school of Marxist economics borrowed from an early American Keynesian, Alvin Hensen, to solve this enigma. Abundance, the result of capitalist re-enhancement, is wasted in one way or another. In Monopoly Capital (1966), Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran identify the growing importance of marketing in the postwar US as serving the key function of wasting capital.

John Maynard Keynes on capitalism in the nineteenth century: “Thus this remarkable system depended for its growth on a double bluff or deception. On the one hand the laboring classes accepted from ignorance or powerlessness, or were compelled, persuaded, or cajoled by custom, convention, authority, and the well-established order of Society into accepting, a situation in which they could call their own very little of the cake that they and Nature and the capitalists were co-operating to produce. And on the other hand the capitalist classes were allowed to call the best part of the cake theirs and were theoretically free to consume it, on the tacit underlying condition that they consumed very little of it in practice. The duty of ‘saving’ became nine-tenths of virtue and the growth of the cake the object of true religion. There grew round the non-consumption of the cake all those instincts of puritanism which in other ages has withdrawn itself from the world and has neglected the arts of production as well as those of enjoyment. And so the cake increased; but to what end was not clearly contemplated. Individuals would be exhorted not so much to abstain as to defer, and to cultivate the pleasures of security and anticipation. Saving was for old age or for your children; but this was only in theory—the virtue of the cake was that it was never to be consumed, neither by you nor by your children after you.” The Economic Consequences of the Peace (Macmillan & Co., Limited), 1919.

To use the words of Depeche Mode, “A Question of Time,” Black Celebration (Sony Music, 1986).

For a fascinating examination of Marshall’s theory of waiting, and also his adoption and then abandonment of Marxian socialism for what we now call marginalism (the cement of the neoclassical school that has ruled economics since the 1980s), see Kiichiro Yagi, “Marshall and Marx: ‘Waiting’ and ‘Reproduction,’” Kyoto University Economic Review 62, no. 2 (October 1992).

Much of political economy can be boiled down to a dreamer refusing to believe they are dreaming.

Noam Yuran, What Money Wants: An Economy of Desire (Stanford University Press, 2014), 39–40.

John Stuart Mill: “When a country has carried production as far as in the existing state of knowledge it can be carried with an amount of return corresponding to the average strength of the effective desire of accumulation in that country, it has reached what is called the stationary state; the state in which no further addition will be made to capital, unless there takes place either some improvement in the arts of production, or an increase in the strength of the desire to accumulate.” Principles of Political Economy, vol. 1 (Parker, 1857), 210.

His concept of transeconomics should not be confused with transhistoricism. The former is about the market as totality specific to a culture we call capitalism; the latter naturalizes the categories of our market culture: wages, profits, money, exchange, and so forth. Baudrillard on transeconomics: “There is something much more shattering than inflation, however, and that is the mass of floating money whirling about the Earth in an orbital rondo. Money is now the only genuine artificial satellite. A pure artifact, it enjoys a truly astral mobility; and it is instantaneously convertible. Money has now found its proper place, a place far more wondrous than the stock exchange: the orbit in which it rises and sets like some artificial sun.” The Transparency of Evil: Essays on Extreme Phenomena (Verso, 1990), 33.

Baudrillard writes: “Exchange value is what makes the use value of products appear as its anthropological horizon. The exchange value of labor power is what makes its use value, the concrete origin and end of the act of labor, appear as its ‘generic’ alibi. This is the logic of signifiers which produces the ‘evidence’ of the ‘reality’ of the signified and the referent. In every way, exchange value makes concrete production, concrete consumption, and concrete signification appear only in distorted, abstract forms. But it foments the concrete as its ideological ectoplasm, its phantasm of origin and transcendence (de passement). In this sense need, use value, and the referent “do not exist.” They are only concepts produced and projected into a generic dimension by the development of the very system of exchange value.” The Mirror of Production, trans. Mark Poster (Telos Press, 1975), 30.

It’s telling that Victorian anthropologists saw Aboriginal Australians as inhabiting dreamtime, but themselves. They, the masters of progress, were in the real; their subjects were lost in a dream. But a culture, no matter what form it takes, demands for its coherence a good deal of dreaming.

Mike Dash, Tulipomania: The Story of the World’s Most Coveted Flower & the Extraordinary Passions It Aroused (Crown, 2001), 167.