In the mid-1960s, the Brazilian artist Rubem Valentim was gaining recognition for his abstract geometric art. Between 1963 and 1966, Valentim and his wife, the art educator Lúcia Alencastro Valentim, visited the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Belgium. They concluded their tour in Senegal, where Valentim took part in the First World Festival of Negro Arts, in Dakar. This experience made a huge impact on Valentim’s artistic practice, as it put him in dialogue with other artists of the African diaspora and broadened his understanding of the ways abstraction can express a pan-African and diasporic language. According to researchers Cláudia Fazzolari and Abigail Lapin Dardashti, this creative exercise was crucial to the incorporation into Valentim’s paintings of a wide color pallete and geometric forms, transforming the artistic repertoire he started with in Bahia in the 1940s and nurtured in Rio de Janeiro in the 1950s.1

During his travels through Italy, Valentim took many photographs, including of art exhibitions. In a set of Polaroids housed at the Research Center of the São Paulo Museum of Art, we see a unique and arresting sculpture: on the floor, two globes seem to be built on flat surfaces that, when intertwined, look like one spheric structure.2 Both pieces are small compared to a bigger sculpture in the background of the photographs, a kind of vertically structured totemic object composed of round shapes and diagonal arrows. The shades of gray on the black-and-white images suggest that the works were very colorful.

At first glance the sculptures in these images appear to be the kind of totemic artworks Valentim was known for—what he termed “emblem reliefs” or “emblematic objects.” But when these photographs were taken, Valentim was years away from incorporating sculptural components into his art. The sculptures in the photographs, in fact, belonged to an African-Brazilian artist from a younger generation with whom Valentim had become acquainted in Italy. His name was Edival Ramosa. Though Ramosa contributed to several international exhibitions, such as “Multiples: The First Decade” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1971, “The Afro-Brazilian Hand” at Museu Afro Brasil in 1988, and “Introspectives: Contemporary Art by Americans and Brazilians of African Descent” at the Californian Afro-American Museum in 1989, he has been largely forgotten by Brazilian art history.3 Ramosa and Valentim, along with artists such as Almir Mavignier and Wilson Tibério, comprise an artistic movement within the post-abolition context of Brazil related to what scholars Kim D. Butler and Petrônio Domingues term “imaginary diaspora,” or “a multitude of individual migrations driven by diverse motivations.”4 Yet Ramosa’s work ought to also be remembered in its own right, as it yields important insights into the racial dimensions of geometric abstraction, and particularly how abstraction can be an arena for racialized expression constructed in diaspora. This essay aims to compose a potential history for Ramosa’s sporadic trajectory, bringing into play discussions on geometric abstract art from scattered archives on both sides of the Black Atlantic to assess his artistic production alongside the challenges of Brazilian and Black art history.

Born in the state of Rio de Janeiro in 1940, Edival Ramos de Andrade was in his early twenties when he voluntarily served as a soldier in the Peace Expeditionary Force that Brazil sent to the Egypt-Israel conflict in Suez. During his passage through the African continent at the beginning of the 1960s, Ramosa visited Cairo several times, as well as the Luxor Temple, the Giza Pyramids, and the Karnak Temple in Thebes. He would later identify this trip as one of the inspirations that would lead him to create art, and it was during this Atlantic voyage that Edival Ramos de Andrade became Edival Ramosa. The reason the artist adopted an Italian-sounding last name is up for speculation. Or could “Ramosa” be a reference to Ramesses the Pharaoh? It’s possible that Cheikh Anta Diop’s focus on Egypt as one of the earliest known African civilizations resonated with Ramosa. From North Africa, Ramosa crossed the Mediterranean and settled in Milan for ten years, between 1964 and 1974. It was in his studio there that he, at the age of twenty-four, committed himself to creating art that was connected to his reality in Brazil but also attentive to the abstract neo-avant-garde and to the Maghreb and the Middle East.

Edival Ramosa, New Totemic Construction, 1964. Collection Gilberto Chateaubriand, MAM Rio de Janeiro, RJ.

In a drawing Ramosa made in 1964, we can see a vertical sculpture unit composed of different parts in red, orange, black, purple, and yellow. At the bottom of the drawing is a phrase written in yellow ink: “Nova construção totêmica,” or “New totemic construction.” This was Ramosa’s term for his visual vocabulary, a style that was evident in the photographs taken by Valentim in 1965. Through this form, the artist expressed his desire for a new attitude toward geometric abstraction, one which sought to portray poetic singularity within a whole, promoted by the repetition of concentric shapes and round objects like circles and semicircles, discs and semi-discs, all in vivid color. Ramosa experimented with shapes influenced by the urban and industrial environment and available materials. His interest in creating a universe of poetic signs and invented constructions led him to produce artworks that the art critic Gillo Dorfles called “object-pictures,” “painted sculptures,” and “useless colorful objects.” For Dorfles, Ramosa’s sign-symbols are

constructions full of inventions and findings, in which the carved and turned wood, varnished with tempera or enamel, sometimes in phosphorescent colors, acquires the precision and cleanness proper to the serial object, and maintains unchanged the handcrafted qualities kept alive by just a small amount of peoples today.5

These “object-pictures,” with names like Bola e coração (Ball and Heart), Árvore multicor (Multicolor Tree), Toy para Leonardo (Toy for Leonardo), and Flag and Symbol, all created in 1966, tried to establish a limit—“with a greater charge of humor,” according to the artist—between the two-dimensionality of the painted surface and the three-dimensionality of the sculpture or object. These materials and chromatic components allowed Ramosa to refine the qualities of his object-shapes as “construction” elements, or, as he put it, ways to “transform the totem into a new kind of symbol, related to handcrafted culture and also to modern media such as enamel, acrylic, tempera colors, among others.”6 Vermilion red, light yellow, silver, white, blue, iron gray, “yellowish,” green, orange, and orange-red are all included in Edival Ramosa’s palette and are applied to wood and acrylic artworks. Such colors accentuate “the transparency of the plastic material, serving as an even brighter and more vibrant inducement and coloration,” creating the effect of rhythms and variations, a vibrant chromatization that, as the Italian art critic Gualtiero Schonenberger observed, underline the works’ optic play and material thickness and pitch in a singular way.7

Ramosa’s engagement with the totem echoes its prominent use by Black Brazilian artists, such as the “relief emblems” of Valentim, the polychromatic totems of Emanoel Araújo, and the works of Juarez Paraíso and Jorge dos Anjos. It is not by chance that Ramosa’s New Totemic Construction sketch was made during a time of intense debate within the arts about what was considered “constructive” in Brazil and abroad.8 These debates around the abstraction of space, time, and the dimensions of processual and experimental art are well known to an international audience familiar with names such as Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark, and Amilcar de Castro, who represent the dominant narrative of geometric abstraction in Latin American art. But Ramosa, with his proposition for a “new totemic construction,” was not trying to join that white lineage of geometric abstraction; he was rather thinking about the racial complexity of abstraction and how race’s structural relations could be expressed in a structurally ascendent—totemic—way.

View of the exhibition “Edival Ramosa,” 1966, at Annunciata Gallery, Milan.

Both Black and Brazilian art history have engaged in rich debates about the relationship between aesthetic abstraction and race. The art historian Huey Copeland has observed that though the art market considers Black abstraction to be a new development, Black artists have been practicing and defining this language since the 1960s and ’70s. Copeland asks, “How do we develop a language, a critical framework, for thinking the multifariously hued abstract work of black artists, male and female, that honors the practitioners’ careful work on the signifier?”9 In an American context, Copeland’s question has been diversely answered by exhibitions such as “Energy\Experimentation: Black Artists and Abstraction, 1964–1980” at the Studio Museum of Harlem (2006), “Blackness in Abstraction” at Pace Gallery in New York (2016), and survey exhibitions on artists like Howardena Pindell and Tom Lloyd, among others. Less commonly explored are questions of how this art history could be developed in a place like Brazil.

How do we think of the relationship between abstraction and race in a diasporic context like Brazil without reinforcing nationalist ideology and the country’s historical white hegemony? Curator and writer Diane Lima can help us answer this question. As she argues in her text “Black Time: Abstraction and Blackness in Brazilian Contemporary Art” (2023), a superficial reading of Black abstraction might reduce and essentialize it, assimilating it into the history of abstraction created by Western art. This history includes debates in Latin America about the notion of the “constructive” in the art of Oiticica, Clark, and Castro. Lima, however, offers a hypothesis about

how concretism and neoconcretism in Brazil create an equation of value that has as a consequence the obliteration (or an attempt at obliteration) of raciality in the modern ethical and aesthetic scene in the country, ultimately making concrete and neoconcrete artists in a sphere of global art the image that is known as synonymous with art in Brazil.10

When contemporary artists perform abstraction, writes Lima,

that is, when they isolate or rule out, with no figurative process, everything that may be seen as excessive in the light of ultra-visibility—such artists make known an enlarged frame of reference based on materiality, ancestry, their own territories, and the aesthetic and theoretical arsenal provided by the diaspora.11

It is this frame of reference created by diaspora and the multitude of individual migrations that Ramosa’s art expresses.

Authors like Lima and Copeland illuminate a long-standing connection that continues to surprise us even today: abstraction and its proposition of creating new artistic meanings for space, material, and color has always been entwined with theories of Blackness.12

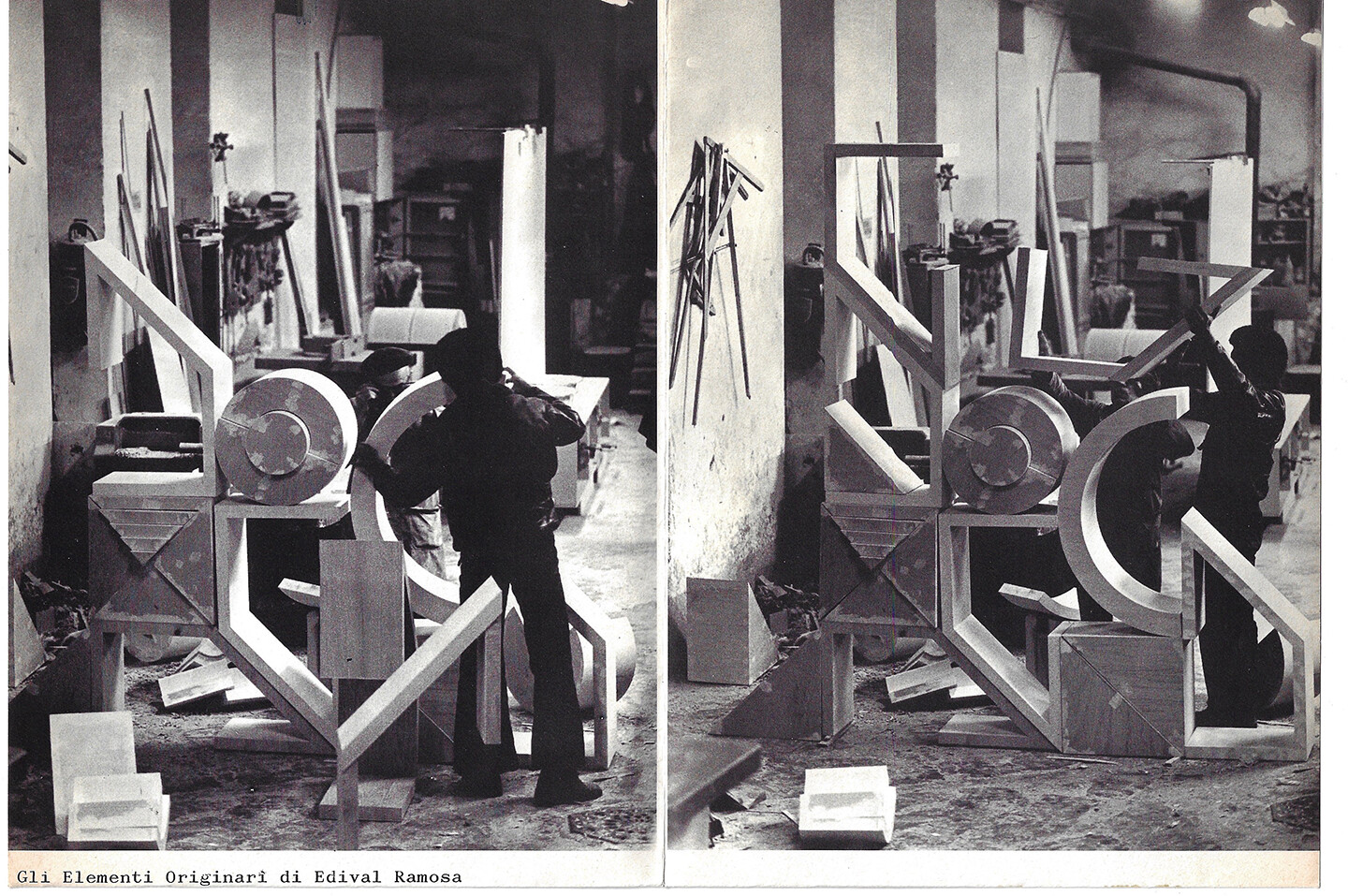

Ramosa’s “new totemic constructions” began to surpass the material and chromatic elements he initially conceived, so he increased the scale of his pieces in order to fill the exhibition space itself. In an image taken of Ramosa in his studio in the early seventies, we can see the artist, facing backwards, with his prominent Afro and a leather jacket, working with an assistant on large-scale pieces. The high ceiling and ample space of his studio provided the conditions to conceive furniture pieces made up of independent parts that could connect with each other, expanding themselves sideways and upward.

Ramosa’s studio was in the Navigli neighborhood of Milan, an ancient area with artificial irrigation channels and transportation via waterways. Over time, the commercial warehouses in the neighborhood turned into art galleries and studios.13 “With his head and his heart full of murky and colorful images of his country,” writes Gillo Dorfles, “[Ramosa] arrived in Milan, Lombardy’s flat and grayish city, and settled on the last floor of an anonymous building, where he could observe the subtle fog above the ‘Porta Ticinese.’”14 Living in his own studio, a two-hundred-square-meter space, Ramosa was able to scale up his object-pictures, adopting designs that would become increasingly environmental. He also worked on commissions, designing decorative tiles and the interiors of barbershops, hotels, and other establishments in his neighborhood.

Edival Ramosa produces painted wood works that resonate with the constructive universalism of Joaquín Torres-García.

Ramosa worked as an assistant for Milan-based artists such as Arnaldo Pomodoro and Lucio Fontana. Gradually, he began to create a universe of his own, participating in art salons and exhibitions. Annunciata Gallery was one of the art spaces where Ramosa was most active, including in group exhibitions in 1965, 1966, 1967, and 1971, and in solo exhibitions such as “Minhas Viagens na África e Europa” (My Trips to Africa and Europe) in 1969 and “Elementi Originari” (Original Elements) in 1972.

In the above-mentioned photograph of Ramosa in his studio, he is working on a piece for the “Elementi Originari” exhibition. Ramosa prepared very meticulously for this show, carrying out many studies and sketches on cardboard, mixing paints in multiple colors, and creating simulations with cutouts and glued paper. After he created the pieces in their actual sizes, they were turned into a playful combination of circles, triangles, and inverted diamond forms, overtaking the gallery’s space. “Elementi Originari” invokes a fellow diasporic artist important to Ramosa—Joaquín Torres-García, whose own idea of “constructive universalism” conceptually and spatially expands Ramosa’s new totemic construction.15

In “Elementi Originari,” Ramosa proposed a poetic conversation with Torres-García’s aesthetic and philosophical doctrine of South American abstraction. Torres-García’s doctrine played a huge role in the canonization of Latin American geometric abstraction, and it remains an influential curatorial framework for geometric art across the Global South. My own understanding of Torres-García comes from scholar Aarnoud Rommens’s analysis of constructive universalism as an inversion of abstraction—that is, as an artifice of ancestral abstraction based on the artist’s nomadic experience. These arrivals and departures, these interruptions and unforeseen drifts, these “scenarios of exile”—which we can connect to the “imaginary diasporas” of Kim D. Butler and Petrônio Domingues—led the Uruguayan artist to create a heterodox aesthetic philosophy.

Rommens’s analysis of South American abstraction helps us understand that its mystery and originality emerge from its “act of construction: the work of art enacts the artifice of origin, an assemblage of an imaginary present out of the contingent ruins of the past projected onto a utopian future.”16 Rommens’s reading of Torres-García’s constructive universalism as a reflection of his nomadic experience illuminates Ramosa’s use of other artists in “Elementi Originari” as “elements that give origin” to new constructions. In the exhibition pamphlet for “Elementi Originari,” poet and political activist Francesco Leonetti examines the connected rhythmic abstractions Ramosa uses to create his artworks, and also considers his production of “cared-for and loose, intense and silent decoration pieces,” affirming that “Edival had the initiative to look for them in a unique expedition to Mato Grosso, with the help of the master of symbols Torres-García.”17 As an anonymous reviewer wrote in the Brazilian newspaper O Globo in December 1971, “[Ramosa’s] works reveal a preference for strictly geometric shapes and vivid colors combined with phantasy, but also with his concern for bright and decorative effects.” Instead of having fixed origins, Ramosa’s constructions fit into each other like large fragments of a colorful puzzle.

The connection between Ramosa’s poetics of abstraction and his diasporic displacement is most vividly demonstrated in his exhibition “Minhas Viagens na África e Europa” (My Trips to Africa and Europe), the first solo exhibition he presented at Annunciata Gallery, in 1969. The title refers to Ramosa’s journey from Rio de Janeiro to Egypt and other North African countries, before arriving in Italy and becoming “Ramosa.” The exhibition consisted of three big compositions—two environmental structures dedicated to Africa, which occupied the larger room of the gallery, and one environmental structure that referenced Europe, in a smaller room.

The first work in the bigger room was O Sol dos Povos de Cor (The Sun of the Colored Peoples),18 “a huge semicircle formed by half discs that overlap in ‘ton sur ton,’ its diameter mirroring itself in a reflective base, while an arrow arranged perpendicularly to the base is enriched by another reflective surface.”19 The half discs had a palette of yellows, oranges, reds, and purples. The second work in the bigger room, Flecha Preta (Black Arrow), was a “transversal [work] formed by longitudinal green, violet, blue, and smoky grey acrylic stripes, its top formed by a reflective triangular base.”20 The figures of the sun and the arrow express an opposition to the third work, which was dedicated to Europe. In a small room of the gallery with a showcase window to the street, “the floor is fully covered with greyish plaster hemispheres” arranged in such a way that visitors were not able to walk through or around the spheres. With this environment piece related to Europe, Ramosa included a quote by Frantz Fanon: “You, who studied in great Universities and made a world of statues.” While we don’t have access to Ramosa’s original text, we can infer that this quote comes from the first chapter—entitled “On Violence”—of Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1961). In this chapter Fanon also writes:

A world divided into compartments, a motionless, Manicheistic world, a world of statues: the statue of the general who carried out the conquest, the statue of the engineer who built the bridge; a world which is sure of itself, which crushes with its stones the backs flayed by whips: this is the colonial world.21

Here, Ramosa draws a direct connection between Fanon and the organization of the gallery: a room/world that is divided, not relational, without the opportunity for public participation.

The Sun of the Colored Peoples, Black Arrow, and Fanon’s Room at Annunciata Gallery in 1969. Later retitled “África-Brazil,” the exhibition travelled to Petite Gallery in Rio de Janeiro in 1971.

In 1971, Ramosa’s Annunciata Gallery exhibition traveled to Petite Gallery in Rio de Janeiro and was retitled “África-Brasil.” A reviewer at the time stressed the attention-grabbing quality of the works: a “huge semicircle, in layers ranging from purple to soft yellow, is reflected in the polished stainless-steel surface: it is The Sun of the Colored Peoples. A little further on, four acrylic bands on a blue triangle form Black Arrow.”22 The latter work recalled the peaked shapes Ramosa used back in the mid-1960—those visible in Valentim’s photographs—now enlarged and pointed toward the ground.

The Sun of the Colored Peoples seems to have had a remarkable impact on local audiences. Ramosa’s use of reflective surfaces aimed to integrate the viewer and the environment into the work. As Ramosa’s brother has commented, “The work stood there and occupied almost the entire space; it was round, made of stainless steel, its top had a beautiful color, acrylics, colors, like a sun, you know, a sun.”23 Other observers connected the image of the sun to Ramosa’s emotional state. The art critic Jayme Maurício, for instance, pointed to Ramosa’s displacement as a component of the sculpture, writing that the “sun and color visited his homeland, made taut by the exile atmosphere.”24 Maurício highlights Ramosa’s diasporic approach, stating that “he seems determined not to return … We are seeing a Ramosa visiting, not a Ramosa returning.” The title of Maurício’s essay, “Ramosa: A Visit That Is Not a Return,” resonates with other critical reviews of Ramosa at the time, like Roberto Pontual’s “The Return, for Good or in Passing” (1974), which linked Ramosa’s situation to Rubens Gerchman, Sergio Camargo, and Almir Mavignier. Maurício’s use of the term “exile” is thought provoking because, unlike artists like Oiticica and Clark, who produced works of art before leaving Brazil for exile, Ramosa began his artistic career when he was already living outside the country.

Ramosa’s allusions to exile resonate with Torres-García’s nomadic experience and with Fanon’s arguments. They also share an aesthetic arsenal with Valentim, Mavignier, and many other Black artists. The Sun of the Colored People reveals trajectories in geometric abstraction that are not fully acknowledged in transnational and diasporic Brazilian art history.

Cláudia Fazzolari, “Rubem Valentim: a riscadura brasileira,” in Ifê funfun: Homenagem ao centenário de Rubem Valentim/Daniel Rangel (Almeida e Dale Galeria, 2022); Abigail Lapin Dardashti, “Negotiating Afro-Brazilian Abstraction: Rubem Valentim in Rio, Rome, and Dakar, 1957–1966,” in New Geographies of Abstract Art in Postwar Latin America, ed. Mariola V. Alvarez and Ana M. Franco (Routledge, 2018).

Before the photos were housed at the research center they were shown in the exhibition “Parable of Progress” at Sesc Pompeia, São Paulo, 2022–23.

Ramosa exemplified what Rosana Paulino describes as the challenge of reading Brazilian visual art, which “implies the creation of new analytical mechanisms, or perhaps the accumulation of different methodologies that allow us to think of broader ways of analysing artistic productions, embracing the multiple meanings emanating from materials, the social contexts, and the different cultures from which artists come.” Rosana Paulino, “Notes on Reading Artworks by Black Artists in the Brazilian Context,” in Decolonisation in the 2020s (Afterall Art School, 2020).

Kim D. Butler and Petrônio Domingues, Diásporas Imaginadas: Atlântico Negro e histórias afro-brasileiras. (Perspectiva, 2020), 33. Almir Mavignier was recognized by the Marxist art historian Donald Drew Egbert as “the negro painter from Brazil who from 1953 to 1958 had studied at the Hochschule fur Gestaltung in Ulm, Germany,” in Social Radicalism and the Arts: Western Europe (Alfred A. Knopf, 1970). Wilson Tibério was a painter and scenographer who, along with founding the Black Experimental Theater with Abdias do Nascimento, received a scholarship to study in Paris in 1947. There, he got involved in the negritude movement, especially with the writer Alioune Diop, founder of the newspaper Présence Africaine. Tibério traveled to Africa, staying for long periods in the Ivory Coast and Senegal, where he participated at the First World Festival of Negro Arts with Valentim.

Gillo Dorfles. “Novo Universo de Sinais / Edival nas neblinas milanesas,” Mirante das Artes, Etc, no. 1 (January–February 1967): 38.

Edival Ramosa, “Fontes e Metas / Edival nas neblinas milanesas,” Mirante das Artes, Etc, no. 1 (January–February 1967): 38.

One of the first exhibitions Ramosa appeared in was “Perpetuum Mobile” at Obelisco Gallery in Rome in 1965, alongside artists like Grazia Varisco, Julio Le Parc, Bruno Munari, and Victor Vasarely. The “optical” elements in Ramosa’s work were also observed by Brazilian critics—see Harry Laus, “Brasileiro faz Op em Milão,” Jornal do Brazil, 1965.

See Sônia Salzstein, “Construção, desconstrução: o legado do neoconcretismo,” Novos Estudos CEBRAP, 2011; Sérgio B. Martins, Constructing an Avant-Garde: Art in Brazil, 1949–1979 (MIT Press, 2013); Camila Maroja, “Vontade Construtiva: Latin America’s Geometric Abstract Identity,” in New Geographies of Abstract Art in Postwar Latin America, ed. Mariola V. Alvarez and Ana M. Franco (Routledge, 2019).

Huey Copeland, “Necessary Abstractions, Or, How to Look at Art as a Black Feminist,” in “Beyond the Black Atlantic, Its Visual Arts,” special issue, Africanidades 2, no. 2 (2023).

Diane Lima, “Tempo Negro: abstração e racialidade na arte contemporânea brasileira,” in Negras imagens, ed. Renata Bittencourt (Instituto Moreira Salles, 2023), 29–30.

Lima, “Tempo Negro,” 28.

See Darby English, 1971: A Year in the Life of Color (University of Chicago Press, 2016); Denise Ferreira da Silva, “In the Raw,” e-flux journal, no. 93 (September 2018) →; and Diane Lima and Denise Ferreira da Silva, “A poética negra feminista: a força, as formas e as ferramentas da recusa,” in Negros na piscina: arte contemporânea, curadoria e educação (Fósforo, 2024).

Elena di Raddo, Milano 1945–1980. Mappa e volto di una città. Per una geostoria dell’arte (Franco Angeli, 2016).

Dorfles, “Novo Universo de Sinais,” 38.

Both “new totemic construction” and “constructive universalism” are facets of how Ramosa dealt with contemporary artistic topics such as space, size and scale. He exhibited both small-format artworks (in exhibitions like “Il Piccolo Formatto,” 1966), and large-scale environmental sculptures (in exhibitions like “L’uomo e lo spazio,” 1967). For the exhibition “Le Linee di Gioia” (1967), presented in Verona and Trieste, Ramosa said he created “a single environmental sculpture, demanding public participation. Much is lost in contemplation. We fix our gaze on a single detail, and we lose sight of the whole.” See Walmir Ayala, “Um brasileiro em Milão,” in Jornal Correio do Povo, March 14, 1970.

Aarnould Roomens, The Art of Joaquín Torres-García: Constructive Universalism and the Inversion of Abstraction (Routledge, 2017), 2.

Francesco Leonetti in Edival Ramosa: Elementi Originari (Salone Annunciata, 1972).

In Brazil today, using the expression “de cor” (colored) to refer to Black people is dated and racist. In Ramosa’s time, however, it was a current expression and did not have such a negative meaning. This why the expression in the title of Ramosa’s exhibition has been translated as “Colored Peoples” instead of the more modern “People of Color.”—Trans.

Gualberto Schonenberger, “África-Europa vista por um brasileiro,” 1969.

Schonenberger, “África-Europa vista por um brasileiro.”

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox (Grove Press, 1963), 51–52.

“A colorida geometria de Edival Ramosa,” O Globo, December 1971.

Author interview with Ramosa’s brother, July 13, 2023.

Jayme Maurício, “Ramosa: visita que não é volta,” Correio da manhã, 1971.

The text is part of a long-term research project on Edival Ramosa, conducted with the support of a 2024–25 Foundation for Arts Initiative (FfAI) grant. The Portuguese version of this text was edited by Aline Scátola and translated into English by Jéssica F. Alonso.