This essay is part of “After Okwui Enwezor,” an e-flux journal series that reflects on the resounding presence of the late writer, curator, and theoretician Okwui Enwezor (1963–2019). Along with a focus on his many innovative concepts like the “postcolonial constellation,” the series presents a wide evaluation of Enwezor’s curatorial and theoretical practice following other similar initiatives, such as the special issue on Enwezor by the journal he founded, Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art. Moving beyond tributes and biography, this series will cover topics such as the relevance of Enwezor’s approach to politics, the limits of the exhibition as a form for critique, his conception of modernity and writing on the contemporary, his nomadic epistemology, accounts of his biennials in Seville, Paris, and Venice as institutional critique, and the specific contribution of non-Western artists in the art world.

***

Much has been written about Okwui Enwezor’s 2002 mobile Documenta XI, which consisted of multiple platforms and expanded Documenta across four continents. Yet little has been written about his return to curating mega-exhibitions in 2006 with the second International Biennial of Contemporary Art Seville (BIASC), entitled “The Unhomely: Phantom Scenes in Global Society.” One of only three editions of BIASC, Enwezor’s edition highlighted the dark changes in the post–Cold War period after Documenta XI.1 The many biennials Enwezor curated in his career welcomed different artists, discourses, and histories that challenged and ultimately changed what was expected of international mega-exhibitions, such as his Gwangju Biennale, which incorporated a series of previous exhibitions in their entirety into the biennial. A deeper look at the second BIASC shows a similar approach to putting on a challenging show, but also reveals a glaring lacuna in addressing the local situation of Seville and its rich history. Reflecting on the second BIASC and comparing it with recent mega-shows in the 2020s such as the 22nd Biennale of Sydney and the 60th Venice Biennale—comparable in budget, preparation time, and use of multiple locations—demonstrates that biennials have shifted from offering farsighted international critiques, to focusing on the ways contemporary art intersects with local political realities as well as wider planetary concerns.

Biennialization in the early 2000s was a trend born of the Euro-American mobility of capital and people. Biennials largely intended to both celebrate post–Cold War “global culture” and to generate income for cities and regions from tourism. The initial impulse for BIASC came from the experience of Seville hosting the 1992 Universal Exposition. As the mayor of Seville stated of the expo, “Most of us sincerely enjoyed this cultural sampling and did not consider it elitist or far removed from our reality or tastes.”2 This statement underscores Seville’s populist and accessible vision for culture and its desire to provide its citizens with a window to world. Besides extending the mayor’s notion of “cultural sampling,” the biennial was also intended to follow the expo in generating tourist income for the city. The mayor’s comment on the expo was likely inspired by his experience visiting the Swiss pavilion there. The Swiss pavilion was assembled by über-curator Harold Szeemann as a Gesamtkunstwerk; it merged a diverse group of Swiss artists spanning the twentieth century—from Meret Oppenheim to Christian Marclay—into a fun and pop-centric exhibition.3 Thus when BIASC was actually in formation a few years later, Harold Szeemann was invited back to Seville to be its first artistic director. Sadly, it would also be his last biennial project, as he passed away two months after the show closed. Szeemann’s BIASC was a light survey show that, according to one critic, “presented no other argument” than the self-referential exuberance of its title, “The Joy of My Dreams.”4 His final biennial was also a fitting mirror of the period’s ecstatic expanse of capital, which was driving the formation of “global culture.” However, this elation was not a permanent feature of BIASC; in the biennial’s subsequent edition, Enwezor changed tack, from a celebration of global culture toward a critical examination of the dark underbelly of this Euro-American cultural hegemony.

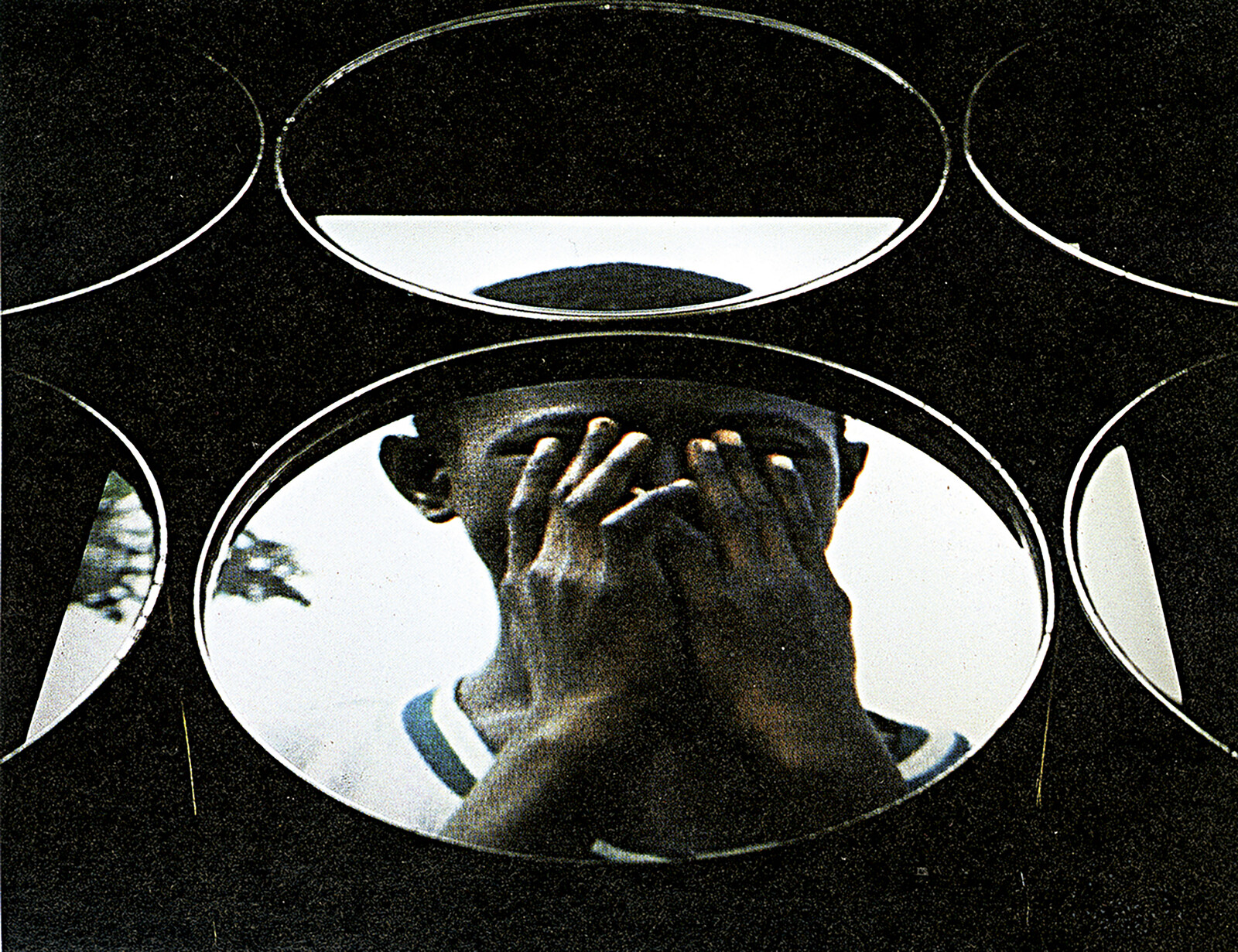

Thomas Ruff, jpeg wi01 (war Iraq), 2004. From 2nd Seville International Biennial of Contemporary Art. Courtesy of the artist and Fundación Biacs.

After his much-heralded Documenta XI and the beginning of his tenure as dean of the San Francisco Art Institute in 2004, Enwezor’s return to curating mega-exhibitions came with the invitation to be artistic director of the second BIASC. The period between the end of Documenta in 2002 and the opening of BIASC was a turbulent moment for so-called global culture, particularly in the United States, where Enwezor had been based since the 1980s. September 11, 2001 rattled the post–Cold War euphoria. The immediate aftermath of the trauma of 9/11 was addressed by a number of works in Documenta XI, including artist Touhami Ennadre’s photographic series September 11.5 The years after 9/11 brought a darker period, revealing the driving force behind global culture—neoliberal capitalism—and laying bare the brutality inherent to its preservation and expansion.

In 2003, the administration of US president George W. Bush spent months manufacturing a fraudulent case to invade Iraq so that the US could secure the country’s oil resources. The Bush administration promoted this false case in global forums, such as the UN Security Council, and in the press—clearly stating the US’s intention to attack Iraq. This sparked a worldwide peace movement, with millions of people taking to the streets in over sixty countries to counter the US’s bellicose plans and to express their opposition to their own countries getting involved. In the face of the single largest anti-war protest in human history in February 2003, the US invaded Iraq the following month, supported by forty-eight other democratic countries, all contravening the clear will of their populations. The thin veil of post–Cold War democracy was punctured, as this illegal invasion revealed corporate kleptocracy as the prime mover of global affairs and global culture. This disillusionment and brutality were the backdrop to the second International Biennial of Contemporary Art Seville.

Before addressing the central argument of Enwezor’s show, I want to work around the edges of the exhibition to explore its peripheral components and also highlight what was not present. I hope this process of demarcating the boundaries of the exhibition—its hinterlands and its absences—will make clear the contrasts between exhibition-making in the mid-2000s and exhibition-making today, in the mid-2020s. Additionally, I hope that working from the outside of the show towards its central thesis will clarify the scope of the exhibition, so that I can discuss Enewzor’s biennial on its own terms.

Starting on the periphery means exiting the gallery doors and beginning with the overall location of the biennial—the city of Seville and the surrounding region of Andalusia. In a catalogue essay for the show, Enwezor outlines “three framing points” for the exhibition: intimacy—understood through both representation and space but also as enclosure and isolation; proximity—reading art as a mediation between spaces and communities; and finally neighborliness—defined as relationships of “recognition, hospitality, friendship, solidarity” between groups and people.6 It is interesting how all three framing devices are important tenants of coexisting in a local community. At the same time, the artist list for the show—one indicator of the show’s interest in the local scene—reveals little connection to Seville or the surrounding area. Only two of the eighty artists in the second BIASC came from or lived in the area, and few works in the show were in dialogue with Seville. This lack of local engagement was noted in press reviews at the time.7

This is not to suggest that if an exhibition includes local artists, it automatically signals local engagement. Rather, this reveals that while the language of community was central to the second BIASC, there was little effort to connect the particular struggles in the city with situations elsewhere. The mode of address of the exhibition was a one-way form of communication, where a dispatch from a community was meant for a more general audience (perhaps a Euro-American audience); it was not meant to be part of a sustained dialogue between two different localities. Without a local grounding, many of the artworks seemed to have more material and thematic connections with other artworks in the exhibition space than with the surrounding community, creating a dialogue within the show that was not contingent on where it took place. Such a biennial could perhaps take place anywhere. It was not necessarily Seville, the region of Andalusia, or Spain that was being addressed; the intended public was “global society,” those with the means and privileges to travel to BIASC or read accounts of it in the press or academic journals. Interpreting the exhibition this way re-positions its three framing points—intimacy, proximity, neighborliness—as ethical guidelines for a “global society” rather than local community guidelines. This “global society” has its own logic, rooted in Euro-American biases, racial prejudices, and fixed canons. Admittedly, the show deployed a diversity of critical perspectives on the present and the past to fracture the rigid epistemologies on which contemporary art and society are based. But even with this important critique, the show spoke in a language that was only comprehensible to the very “global society” it was taking to task, overlooking local texture and history. Incorporating these local elements could have resulted in a more original and unexpected critique.

The second BIASC can be contrasted with many biennials from the 2020s, where locality and even indigeneity have been starting points for mega-exhibitions. For example, the 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020) was curated by artist Brook Andrew, the first Indigenous artistic director in the biennial’s history. Andrew titled the show “NIRIN” (meaning “edge”), a word from the Wiradjuri people of western New South Wales, Australia, the Aboriginal group to which his mother belongs. The show incorporated a number of Indigenous Australian artists alongside international artists and collectives that were mainly themselves Indigenous or diasporic. Despite this “hyperlocality,” the show was anything but parochial; it wove together local and planetary concerns through the diversity of the artists’ work. I do not intend to set up a qualitative distinction between “NIRIN” and “The Unhomely,” as Enwezor and other curators of his generation laid the groundwork for institutions to accept show proposals such as “NIRIN.” Yet this contrast highlights the way that artistic directors of biennials have shifted their engagement with a show’s immediate locality over the past two decades.

Cinémathèque de Tanger, Tangier, Morocco. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Another hinterland of the second BIASC was the regional history of Seville and its long durée. The region of Andalusia, Spain was ruled for almost a thousand years by the Middle East-based Umayyad Caliphate. Addressing such a colonial history could have added a nuanced texture to the other important postcolonial perspectives on display in the show. As one of the few places in Europe subject to a long-term loss of sovereignty by an extra-European force, there was an opportunity to dwell on the history of Andalusia and connect it to the ongoing violence inflicted on the Islamic world by Europe and the US. But perhaps Enwezor felt that, given the rampant Islamophobia in Europe and the US at the time, talking about a history of “Islamic takeover” would only add fuel to the fire. Instead of exploring local Islamic history in Seville and the surrounding Spanish region, Enwezor extended the biennial to the Maghreb by collaboration with the artists Yto Barrada and Bouchra Khalili. They showed their project Cinematheque de Tanger—a historic cinema and cultural center that aimed to preserve the moving-image history of the Maghreb—and also programmed a film festival for the biennial, one that featured artists and filmmakers predominately from the Middle East, as well as diasporic artists in Europe.

The second BIASC grappled with a postcolonial discourse that was prominent in the Euro-American context in the early 2000s. This engagement was underscored by the reprinting of Achille Mbembe’s now-iconic text “Necropolitics” in the exhibition catalogue. Postcolonial discourse also manifested in the show’s examination of how mobility (or its myth) was shifting, as highlighted in the exhibition’s title, “The Unhomely.”8 Tackling the increased obsession with “national security” after 9/11, the show addressed the EU’s militarized response to migration from Africa and the Middle East, as evidenced by its founding of Frontex in 2004. This new border regime underscored that the “mobility” biennials relied on was for the privileged few. However, the show overlooked a local postcolonialism situation by not addressing Seville’s history under the Islamic Umayyad Caliphate. Enwezor instead privileged a discourse on mobility, writing that “in this time-space we are in constant contact with people, goods, images and ideas that are permanently on the move, in constant circulation, reconfiguration, tessellation.”9 This focus on mobility is consistent with a critical stance on “global society,” but this critique also works within the ontology of that very global society. This mobility discourse also recalls the model of Documenta XI, with its multiple platforms across four continents—conceived in pre-9/11 times, unlike the second BIASC. Perhaps the idea of “the unhomely” also addressed Enwezor’s own transience. In a late interview he reflected on his childhood in Nigeria during the Biafran War, which forced his family to move dozens of times: “I learned what it means to be the Other, even within the rooms of one’s own home.”10 Later in life he moved to New York and became part of the first generation of “global” curators, which also included Hou Hanru, Catherine David, and others who circulated through biennials and arts institutions across the planet in the early 2000s.

We Were Here, directed by Fred Kuwornu, 2024, film still. Courtesy of Do The Right Films.

It’s instructive to contrast Enwezor’s BIASC with the recent 60th Venice Biennale, entitled “Foreigners Everywhere” (2024) and curated by Adriano Pedrosa, who has been the director of the São Paulo Museum of Art for the past decade. The title of the Biennale sounds like it might be a reference to “global society,” but in fact it’s the name of an anti-racist immigrant support group in Venice that aids refugees and other migrants trying to reach Italy. The show explored the mobility not of the art class but of the most vulnerable, asking how migrants navigate the local context. While Pedrosa stated that the exhibition focused on queer, Indigenous, and outsider art, many of the works made an explicit effort to speak to the local context.11 One example is the moving image work We Were Here: The Untold History of Black Africans in Renaissance Europe (2024), by the Italian Afro-descendant artist Fred Kuwornu, who focuses on Black Africans’ long history of representation in, and contribution to, the development of visual culture in Europe. Extending the exhibition’s theme, the section “Italians Everywhere” compiled dozens of artists and artworks from the long twentieth century to highlight the country’s own experience of emigration and its former citizens’ external contributions. Many of the artists in the show had also worked with Pedrosa previously during his decade of local programming for the community in São Paulo, and Latin America more broadly.

Enwezor’s BIASC dwelled on dark post-9/11 themes of war, terrorism, migration, and the extractivist nature of neoliberal capitalism. As I write, two unjust conflicts rage in Ukraine and Palestine; the second BIASC showed that the effects of such wars on art and exhibition-making can be deep and long-lasting, resurfacing years later. The exhibition participated in the wave of perennialization that took hold in the early twenty-first century, but also tempered the enthusiasm for the new neoliberal world order that was solidifying around the globe. Most recent mega-exhibitions in the 2020s, such as those in Sydney and Venice, have offered similar critiques of neoliberalism, but have been grounded more deeply in local political and artistic discourses. As the notion of center and periphery in the global art world continues to unravel, this attention to local histories and discourses highlights a multiplicity political, economic, and social experiments. These more recent shows underscore the uniqueness of their localities and, through trans-local cultural discourses, provide meaningful examples of what a postcapitalist world might look like.

Enwezor, working in the early 2000s in an arts discourse still dominated by a predominately white Euro-American canon, made considerable strides in dismantling the expectation that biennials and mega-shows should replicate this cannon. Later, he shifted toward undoing the art-historical epistemologies that substantiated such cannons—for example, in his exhibition “Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965” at Munich’s Haus der Kunst in 2016–17. However, the second BIASC showed that Enwezor’s approach to exhibition-making in the early 2000s, while expansive in its artists list, geographies, and social considerations, tended to overlook the locality of the show itself. The second BIASC seemed to function as a closed cultural biosphere—one rich in artistic diversity, but operating in a different ecology than the surrounding environment. This does not detract from the way Enwezor’s exhibition challenged dominant global narratives at the time; it only underscores the missed opportunity to discover how a local environment could contribute to such a critique.

The first BIASC was curated by Harold Szeemann in 2004. Enwezor’s second edition was in 2006. Peter Weibel, Wonil Rhee, and Marie-Ange Brayer curated the third BIASC in 2008. The latter opened three weeks after the trading firm Lehman Brother’s announced its sudden bankruptcy, which would spark a global recession whose economic effects would bring an end to such extravagant cultural spending, including the BIASC itself.

Alfredo Sanchez Monteseirin, “Forward,” in The Unhomely: Phantom Scenes in Global Society—2nd International Biennial of Contemporary Art of Seville, ed. Okwui Enwezor (Fundacion BIASC, 2006), 9.

Harald Szeemann: with through because towards despite—Catalogue of all Exhibitions 1957–2005, ed. Tobia Bezzola and Roman Kurzmeyer (Springer, 2007), 563–69.

Carlos Jimenez, “The Joy of My Dreams: First Seville Contemporary Art Biennial,” Art Nexus 3, no. 55 (January–March 2005): 104.

Documenta and Museum Friedericianum Veranstaltungs-GmbH, Documenta 11 Platform 5: Exhibition Short Guide (Hate Cantz Verlang, 2002), 70.

Okwui Enwezor, “The Unhomely: Phantom Scenes in Global Society,” in The Unhomely, 16.

See, for example, Ángela Molina, “El aurífero sevillano,” El Pais, November 4, 2006 →.

Although uncredited, the term “unhomely” likely came from postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha’s essay “The World and Home,” Social Text, no. 31/32 (1992). Many thanks to Serubiri Moses for the reference.

Enwezor, “The Unhomely,” 15.

Jason Farago, “Okwui Enwezor, Curator Who Remapped the Art Work, Dies at 55,” New York Times, March 18, 2019 →.

Adrian Pedrosa, “Introduction: 60th Venice Biennale,” January 31, 2024 →.