In the current political climate, neither your average plutocrat nor cultural administrator is ready to tolerate the “autonomy” of cultural and educational institutions, whether in the vein of pluralism or partisanship, even when a genocide is unfolding before our eyes. (And forget about enjoining historical and geopolitical context.) This makes it ever more clear that autonomy’s philosophical aesthetics should be approached in a spirit of genealogical-critical inquiry but also contested—not just discursively, as it has been for years, but also practically.

In January, Donald Trump will begin his second term as the president of the United States. His first term and his campaigns have been defined by the extreme and effective loosening of the constraints of “reality” on previously unimaginable levels of power. His critics are often hampered by confusion over whether his policies are guided by any intentionality or foresight. His actions mix transactional plays with intoxicating chaos, to an extent that last month multiple former high-ranking US military officials from his previous administration agreed that Trump is “fascist”—a sentiment likely circulating within the world’s most powerful military that he will soon lead again, at least nominally. But Trump’s radicality and pathological intensity in courting chaos threatens more than just military structure or policy, and is not only about the already fragile concepts of “truth” and “facts,” but about a much higher order where reality itself is structured. Developing literacy in this domain will be essential for geopolitics in the difficult years ahead.

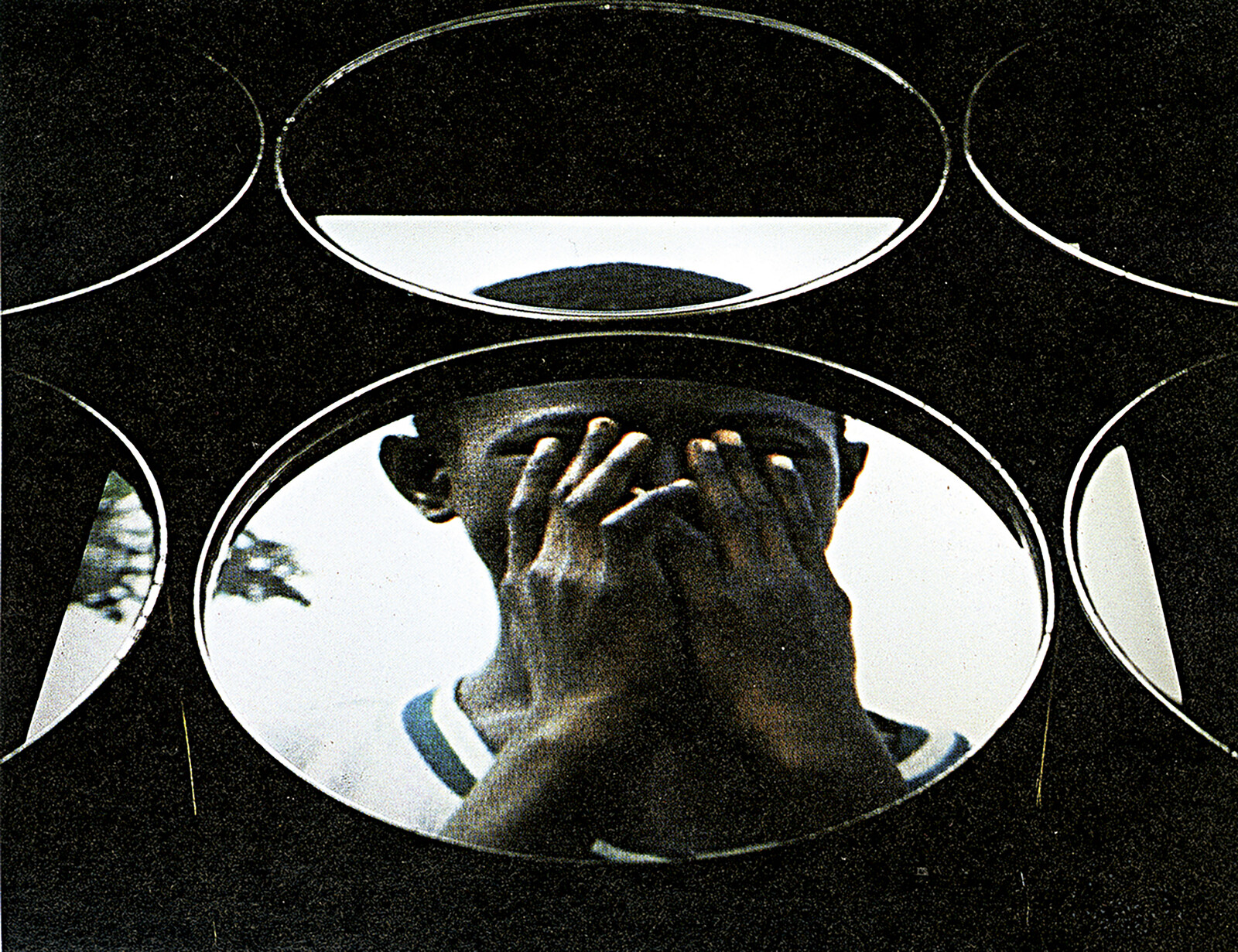

Our mind makes predictions about what it thinks we will see, and shows us hallucinated projections of the near future. When a baseball batter sees a ball traveling towards them, they’re not seeing the actual ball, but a hallucinated projection of where the mind thinks the ball will travel. The batter swings at the hallucination. If all goes well, the hallucinated ball is temporally synched to where the actual ball should be. When we zoom out from the mechanics of motor function and temporal synchronization, the story of visual perception becomes even more unstable.

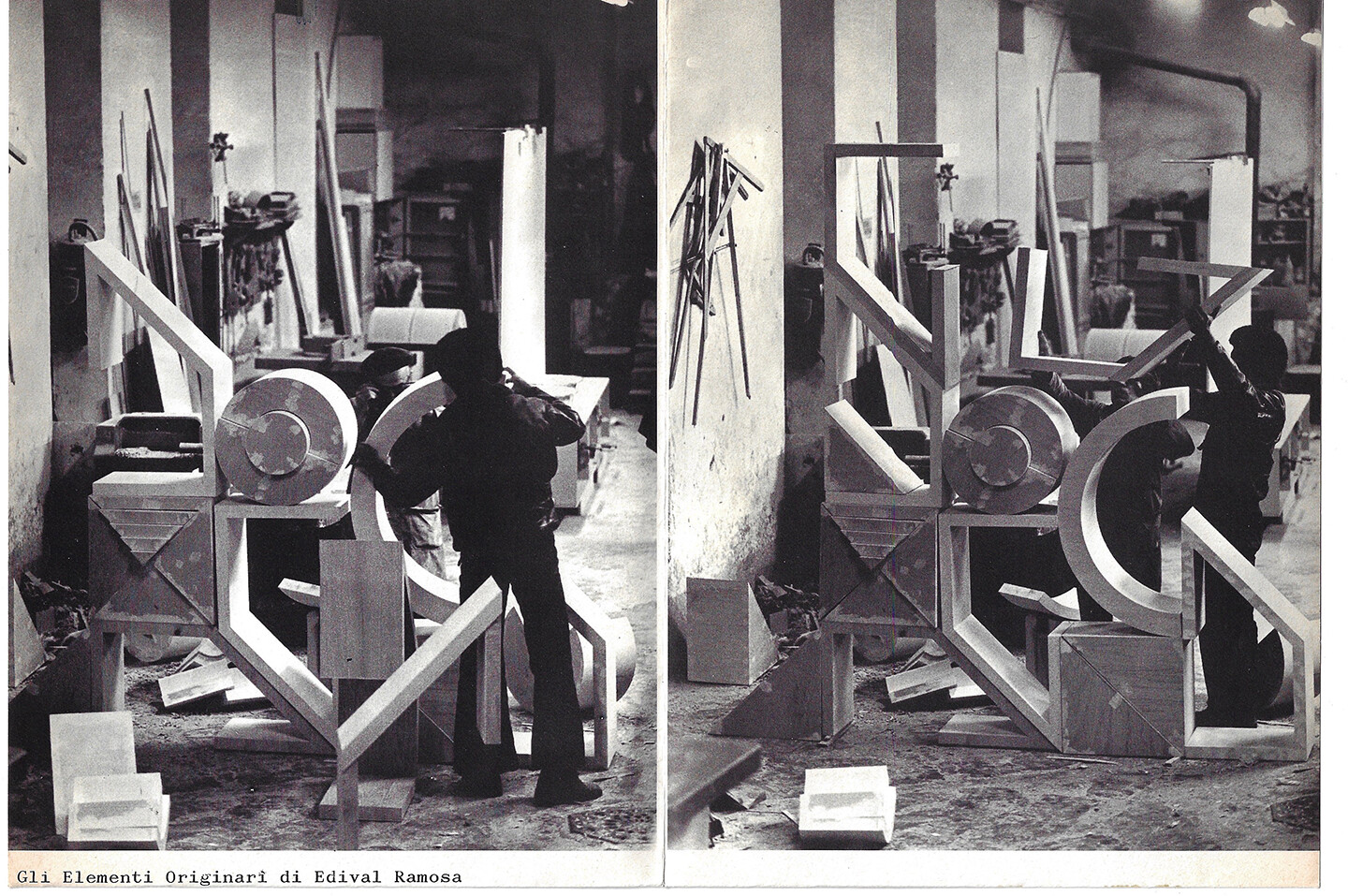

It is not by chance that Edival Ramosa’s New Totemic Construction sketch was made during a time of intense debate within the arts about what was considered “constructive” in Brazil and abroad. But Ramosa, with his proposition for a “new totemic construction,” was not trying to join that white lineage of geometric abstraction; he was rather thinking about the racial complexity of abstraction and how race’s structural relations could be expressed in a structurally ascendent—totemic—way.

Enwezor’s International Biennial of Contemporary Art Seville dwelled on dark post-9/11 themes of war, terrorism, migration, and the extractivist nature of neoliberal capitalism. As I write, two unjust conflicts rage in Ukraine and Palestine; the second BIASC showed that the effects of such wars on art and exhibition-making can be deep and long-lasting, resurfacing years later. The exhibition participated in the wave of perennialization that took hold in the early twenty-first century, but also tempered the enthusiasm for the new neoliberal world order that was solidifying around the globe.

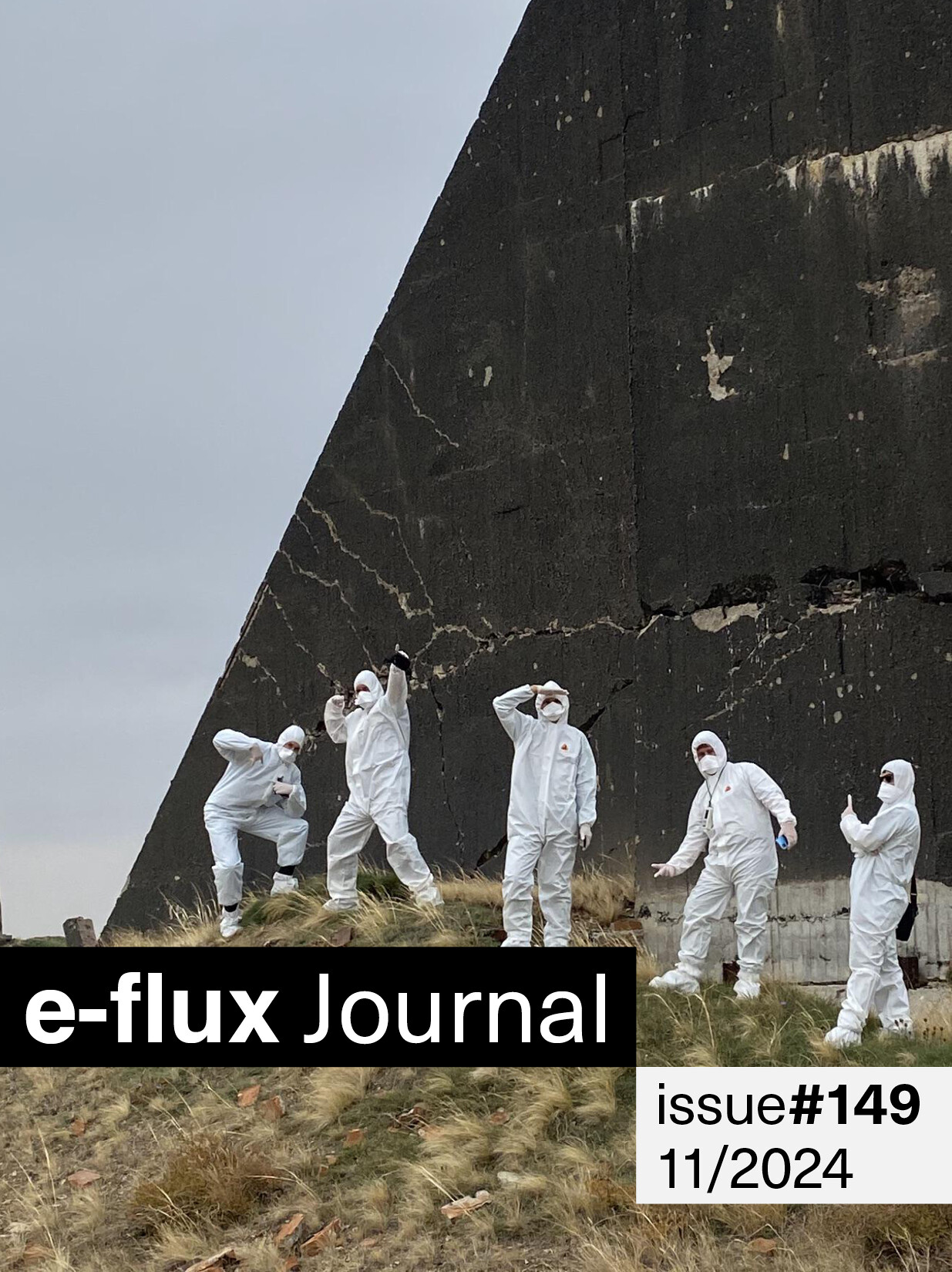

In ORTA’s Spectacular Experiments, which are always site-specific, mise-en-scène arises from the unpredictable monologues, sounds, and movements of a wide variety of people on the one hand, and equally surprising, mobile, sometimes exceptionally large-scale trash compositions on the other. One can always sense the endless, un-appropriable movement of thought and matter fluxes that carry, permeate, and reassemble all the moments of the performance, plunging it into a zone of indistinguishability between the imaginary and the real.

For Choi, time becomes fused and stuck around trauma. To experience profound grief is to be taken out of the flow of time, yet “temporal magic” is what allows for an escape from the inexorable and crushing movement of history: grief as resistance and resistance as grief. There are very good reasons to lose one’s narratives, both as individuals and as nations. One of the goals of experimental writing like Choi’s is to disrupt official narratives, histories, and images along with, more importantly, their meanings—although they’re more like presumptions and predispositions—because narrative is a prime vehicle in which to smoothly embed them.

Even within this range of action, liberation and individual rights have been the cornerstones of disability activism from the 1970s onwards, and the academic discipline of disability studies that followed close behind. In the 2000s, however, thinkers such as Robert McRuer and Eli Clare took a more transgressive approach, reappropriating the figure of the “crip” or the “freak,” defying normative categories with a middle finger raised. In refusing assimilation to—or “accessible” amendments of—the status quo, the crip is revolutionary, avant-garde even. The crip wants a total reconfiguration of norms, not just ramps and closed captions.