Perversion

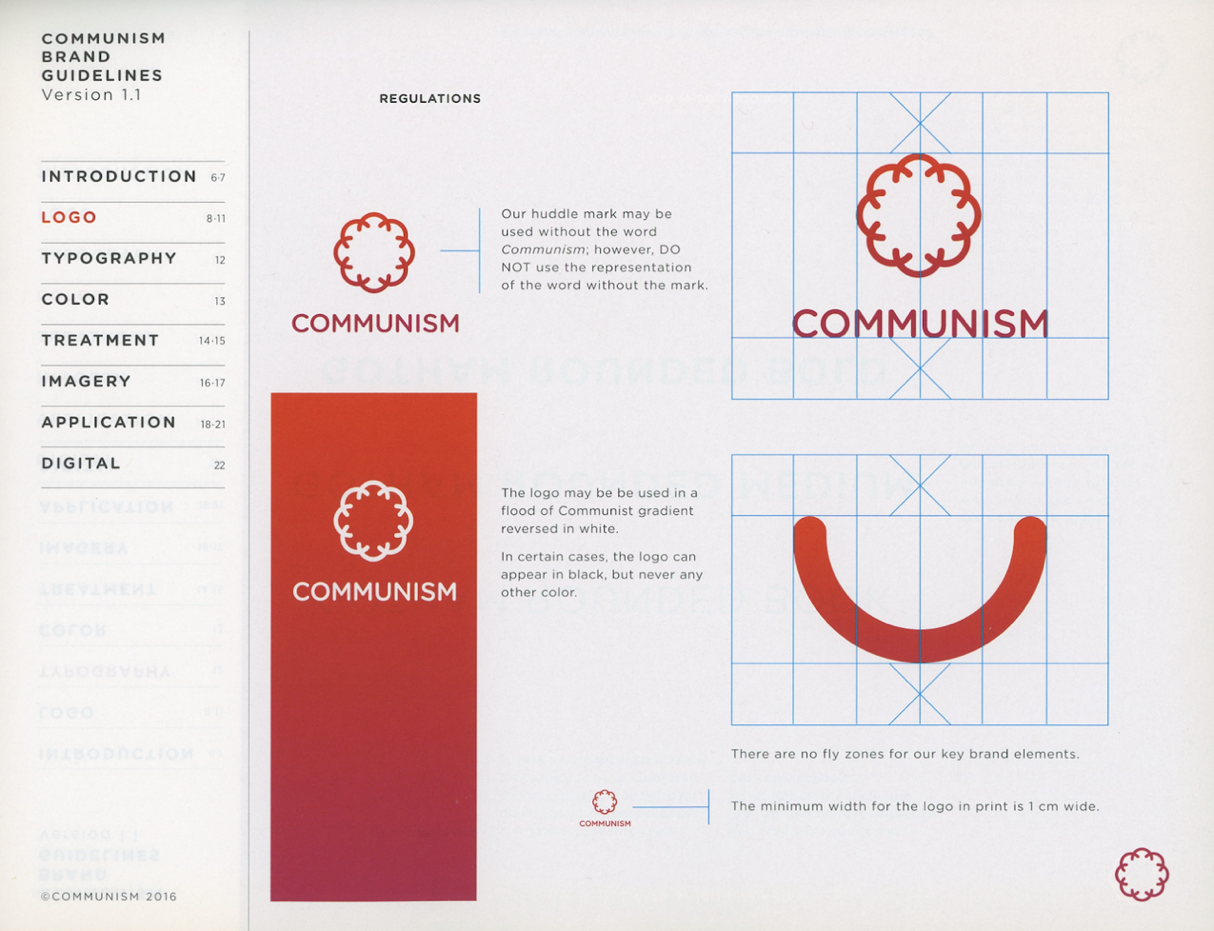

In 2011 an art collective called the Propeller Group (TPG) collaborated with an ad agency called TBWA/Vietnam to develop a campaign that would “promote a positive brand identity for communism.” TPG worked closely with TBWA, the company responsible for Apple’s Think Different campaign for Vietnam, to produce an elaborate brand identity and logo that could adorn a wide range of products, from tote bags and business cards to construction hard hats. The art-project-as-media-campaign culminated in a video called Television Commercial for Communism.

In the video, a conspicuously multiracial cast in white clothing inhabits a staged white environment, surrounded by furniture and trees made from cutout paper. In one frame, the members of a nuclear family nod to one another across a dining room table; in another, a man strums his guitar in performed bliss while gazing into the distance. The live-action scenes are mixed with an animated world of equally cheery, generic characters, who carry colorful crescent shapes. “We all make the same living … share all the world … live as one and speak the language of smiles,” a voice-over says. The people hold up their crescents—the smiles—to one another and join them to form a huge circle. This circle then morphs into a flag at full mast, underwritten by the caption “This is the new communism.” This video was exhibited in the 2012 New Museum Triennial “The Ungovernables,” then in the Guggenheim’s 2013 exhibition “No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia,” and later as part of TPG’s solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in 2016.

According to TPG members Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Phunam, and Matt Lucero, the project drew on input from a focus group they organized that “presented a range of views, from a Chinese American, Vietnamese American, Vietnamese, Indonesian, Indian, and a Tibetan.”1 The Tibetan participant, Tsering Tashi Gyalthang, was reportedly skeptical, as he had faced repression from the Chinese government. “Of course, we weren’t promoting the ideology of communism,” TPG explained to him. “Rather, we [were] exploring its relationship to capitalist ideology in the form of the television commercial, which we think nods to a larger global shift in the marketplace today.”2 Gyalthang found this answer reassuring and agreed to work with TPG as video director, contributing decisions that became central to the final video. He decided, for example, that the actors would stand entirely still as the camera panned around them, rendering them in contrived states of joy. “Seeing the actors immobile,” a TPG member elaborated, “with big smiles, captured these comments of happiness and ‘humanism’ promised by the communism in the commercial—and it made that communist dream of happiness seem slightly perverse.”3

The Propeller Group, “Communism Brand Guidelines” booklet, produced for a Propeller Group exhibition at MCA Chicago, 2016.

TGP was indeed responding to a societal context that is perverse. Though it is still called the Communist Party, the body that governs Vietnam today could hardly be regarded as committed to communism in practice. Though it could be argued that this rift between the regime’s actual governance and Marxist-Leninism opened much earlier—after the North’s takeover during the Fall of Saigon after 1975, and perhaps even back to the Viet Minh’s consolidation of power after the 1945 August Revolution—the specific dissonance that Television Commercial for Communism highlights is life after the 1986 economic reforms known as “Đổi Mới” (“renovation” or “innovation”), which transformed Vietnam into a market socialist economy.

After failed prior attempts, the Đổi Mới reforms successfully reconstructed the country through free-trade policies. After the political resolution of the Third Indochina War and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the United States lifted its trade embargo on Vietnam in 1994. Following recommendations by the IMF and World Bank, the country privatized its state-owned enterprises after reaching a bilateral trade agreement with the United States in 2002, and entered the World Trade Organization in 2007. From 2000 to 2009, the public sector shrunk from employing 60 percent to 20 percent of the population, as the workforce underwent “equitization,” or the transfer of public assets to the private sector.

Opinions are split on how best to refer to the present period in Vietnam. Some scholars prefer “late socialism,” which signals a continuation or direct derivative from prior systems of governance.4 Less common is the term “post-socialism,” which remains a misnomer because the Communist Party still governs and would censor a word that indicates otherwise. Yet the controversy and baggage of this term—of twentieth-century Cold War dichotomies that are outdated yet maintain a strong hold on the public imagination—make it more instructive than the more common “late socialism” or “socialism with Vietnamese characteristics.”

Vietnam’s reforms are comparable to China’s, which saw a similar trajectory of marketization following an era of centralized planning and collectivization under continued single-party rule; in Chinese academic discourse, “post-socialism” emerged after the renovation period to specifically describe post-Mao state socialism. As the film historian Jason McGrath writes of Chinese art and literature after the 1990s,

in many ways, this postsocialist condition is shared with the societies formerly subsumed under the Soviet Union and its allies and satellite states, in that, despite their differences, all these states were under the rule of Communist parties with their origins in the 1919 Comintern and the Bolshevik model of the “dictatorship of the proletariat.”5

Writing in 1989, the historian Artif Dirlik optimistically describes post-socialism as a “radical vision of the future” that “offers the possibility in the midst of a crisis in socialism of rethinking socialism in new, more creative ways.”6 Yet today, in the aftermath of organized communism’s chaotic disintegration across Eastern Europe, “post-socialism” carries a much more negative connotation. It’s a condition that, as scholar Shu-mei Shih describes, is “constituted in the wake of the failure of twentieth-century revolutionary projects” whose collapse “hastened the onward march toward market economy and neoliberalization, which instituted the liberal humanism of the market as the implicit standard.”7 In this sense then, Shih argues, post-socialism is a nonlocalized condition that not only impacts countries that underwent decommunization but affects people globally and demands a non-unitary perspective on the world.8

While the Vietnamese independence movement became a major symbol of Third World resistance for the global left in the twentieth century, and today remains a popular historical comparison, there has been markedly less outside interest in what has become of the project. Within Vietnam, these reflections are mediated—or in some cases, chilled—by a government still in possession of its old censorious powers. This makes it a rich subject for contemporary art with all its abstraction. Art made within Vietnam and across its diaspora after 1989 contains post-socialist observations that are at times nostalgic and ambiguous, at times disenchanted and cynical.9 Post-socialist art may poignantly reflect the current dissonance—or perversion—of Vietnamese society; at the same time, it risks contributing to a misrepresentation of the country’s complex past and the way it presently operates.

What is Post-socialist Art?

Post-socialist art refers to work made not only in a particular period, but work made possible by particular structural shifts—starting with the opening of communication channels and the rest of the world. It is distinguished by the escalating mixture of private and state—as well as local and international—funding for artistic production and its networks of distribution. Describing these circumstances as they relate to the film industry, scholar Mariam Lam identifies Nguyễn Võ Nghiêm Minh’s 2004 Mùa Len Trâu (Buffalo Boy) as an unprecedented post-socialist film that was primarily shot in Vietnam but largely funded by external sources—highlighting the ways that state-owned production houses selectively collaborate with private entities and foreign film enterprises to compete with the globalized film industry.10 Similar influences were at work in the formation of the Propeller Group as an advertising-adjacent art collective. Members Tuan Andrew Nguyen and Phunam described their early evolution as such:

We realized that recording in public without government permission was dangerous. Advertisers, on the other hand, were supported and granted access to public spaces. Accordingly, the group opted to incorporate as an advertising company and obtain a film studio license—to be able to film in public spaces and to distribute content via cinemas and television.11

The most emphatically post-socialist work directly references Marxist-Leninist aesthetics and culture. One can think of Study of the Fluctuation of a Shadow (2014) by the Hanoian artist Nguyễn Huy An, who is also a member of the performance art collective the Appendix Group. The minimalist drawing depicts the outline of the statue of Lenin in Hanoi, including an equation that the artist devised through calculating the area of the shadow cast by the statue at three o’clock in the afternoon. Though the sketch is reminiscent of a chalk outline of the dead, the description of the artwork remains neutral, simply stating that it is a reflection on “the undeniable significance of Lenin as a political figure in the history of Vietnam … and the way our logic, ideals, and world views have always been contained and impacted by natural forces beyond our control.”12 Such an ambiguous description is customary for art exhibited in Vietnam, and always hints at an effort to evade the state’s stringent censorship of any kind of political criticism.

Though in most cases the outright position of the artist who references socialist iconography is hard to discern, some artists do express nostalgia verging on sentimentality. In Trần Minh Đức’s 2019 exhibition “We Are Happy to Learn to Be Stars” at the Factory Contemporary Art Gallery in Ho Chi Minh City, the artist took found photographs of schoolchildren performing the choreographed socialist dance “Pink Lotus” and arranged them on a wall, next to a wooden table on which the artist displayed a collection of Đội Viên (Ho Chi Minh Young Pioneer Organization) books. Offering instructions on “how to be a young Communist member” (quy tắc đoàn đội, trò chơi tập thể, trò chơi đoàn đội), the books contained illustrated lessons for schoolchildren which were suffused with political ideology, moving seamlessly from “how to tie a red scarf” and “how to move in a group” to “how to salute Uncle Ho.” The installation is personal, building, as Trần told me in an interview, on his childhood spent singing in a socialist choir, and reflecting “the belief of a person who is born from a socialist country with all the personal, familial memories.”13 As part of the exhibition, Trần staged a performance for which he invited schoolgirls to perform a “Pink Lotus” dance. One by one, the schoolgirls came on stage, in matching pink uniforms and hair accessories, holding orbs of light. They performed a song called “Counting Star” with a static choreography. “People know the big side, the big history,” Trần recalled. “These are the little things that I know, the little happier stories that I would share. When the counting star song is performed, it lights up a memory that is inside already, how it’s like growing up as a socialist teenager, the formation of the belief.”14

Trần Minh Đức, Đếm Sao (Counting Stars), 2019, documentation of performance at the Factory Contemporary Arts Center, Ho Chi Minh City.

Trần’s work resonates with what the art historian Chang Tan terms “communal aesthetics.” This refers to art that engages with the communist legacy in China and with Mao’s slogan “art for the masses,” in order to revisit how ideologies were felt and lived. These reenactments commemorate personal and collective experience, searching this legacy for an alternate methodology that “explores the communal aspect of art—to create, no matter how fleetingly, an aesthetic utopia where the joy of discovery, expression and creativity is integrated with everyday life.” Communal art, as Tan writes, is impossible to reproduce or even document because its material is mainly memory. Even “being there” does not guarantee participation; the performance activates the shared knowledge and experiences that are particular to a community.15

Another work that revisits the country’s socialist history with surprising ambiguity is Vietnamese-American artist Hương Ngô’s In the Shadow of the Future (2019). The mixed-media architectural installation references the communal housing structures designed by Jean Renaudie and Renée Gailhoustet in Ivry-sur-Seine, one of Paris’s so-called banlieues rouges (red suburbs), where many Vietnamese refugees fleeing the War settled. Within the wooden trilateral sculpture modeled after the star-shaped terraced housing complexes, three monitors display a video of a cosmonaut loitering in the neighborhood, interacting with local residents from two unions called l’Union des Jeunes Vietnamiens de France and l’Union Générale des Vietnamiens de France. The cosmonaut is based on Phạm Tuân, a Vietnamese fighter pilot, who became the first Asian space traveler in 1980 when he went into orbit with the Soviet Intercosmos program, as part of the USSR’s “friendship diplomacy.” On the wall hangs a concrete relief of a newspaper clipping that touts the mission’s victory for the Communist Party of Vietnam. In the Shadow of the Future poignantly imagines the communist spirit persisting in these refugees who fled their country to practice communal living elsewhere. Their journey tracks a continuation of the communist tradition, one that is both diasporic and disentangled from the nation-state.

Huong Ngo, In the Shadow of the Future, 2019, video, still.

Yet what characterizes most post-socialist art is not the continuity but the break––one that’s reflected in narratives around Đổi Mới. In 1994, the year Bill Clinton lifted the trade embargo on Vietnam, a New York Times article reports, “Pepsico imported the first Pepsi-Cola flavor concentrate the day before the embargo was lifted and began distributing the drink an hour after the White House announced the end of the trade ban.”16 A popped bottle overflowing with pent-up fizz is a fitting image for contemporary art’s arrival in Vietnam, after Đổi Mới opened up the country to the world. In a catalog for the exhibition “Uncorked Soul”—one of the first overseas exhibitions of contemporary Vietnamese art, held at Plum Blossoms Gallery in Hong Kong in 1991—the art critic Jeffrey Hantover compares Đổi Mới to reform movements such as glasnost and perestroika. Hantover quotes a Vietnamese artist who declares that, thanks to the transition, “originality and diversity had begun to replace the monotony of the collective.”17 As art historians Nora Taylor and Pamela Corey write, “In the early 1990s, it was as if all writing on art centered on this image, the allegory of the once repressed and now suddenly free, liberated, and liberal Vietnam.”18

While Taylor and Corey question whether the adoption of a market economy in Vietnam translated into a radical refashioning of the arts, it is clear that art after Đổi Mới rejected depictions of collectivity, which now bore the signs of the “old repressive and autocratic regime.” Post-socialist art is thus distinguished by this burst of subjectivity that signaled the end of a period of repression.19 This crude dichotomy between collective conservatism and individualist freedom of expression has long been enforced by the state itself. After the Viet Minh’s victory and the formation of the Cultural Association for National Salvation in the 1940s, there were fierce debates among Marxist intellectuals about the relationship between politics and aesthetics. By the 1950s, the Party implemented crude, restrictive guidelines for artistic production. Socialist art was defined against an enemy—the perceived bourgeois decadence of the West. Take Hồ Chí Minh’s famous response to an exhibition at the Cultural Association for National Salvation in 1945: “All these paintings are very beautiful but these are upper-class beauties. Why don’t you make paintings about lower-class beauties around us?” Similarly, in Trường Chinh’s 1949 “Marxism and Vietnamese Culture,” the general secretary of the Communist Party denounced “cubism, expressionism, and avant-garde art forms” as “sprouted from the rotten wood of imperialist culture.” Post-socialism is, then, a reaction to a reaction.

Contradiction

In 2006, The Propeller Group member Tuan Andrew Nguyen (who has built a successful solo career after TPG’s official retirement in 2016) created Proposals for a Vietnamese Landscape, a series in which he collaborated with a painter who had been employed by the Vietnamese state to paint socialist mobilization posters. One painting in the series, of a sidewalk in Saigon, features a large poster advertisement for Yamaha, where a young woman, sporting jeans and a leather jacket, straddles her new motorbike. She foregrounds what looks to be a spacious vacation house, surrounded by palm trees. The sign reads, “Yamaha New! Pop! Classico! Yamaha Pop Mới.” Directly below the advertisement is a socialist-realist poster in which a group of people face a manufacturing plant in unison as a celestial hammer and sickle casts light over their faces. That text reads, “Tinh thần ngày nam bộ kháng chiến bất diệt,” or “The spirit of the southern resistance war did not die.”

The painting evokes competing notions of “the good life,” where people are “drawn into competitive striving and the accumulation of private wealth to keep up with market demands, even as the socialist ethos of harmony, equality, and mutuality persist in official and popular discourse.”20 There is performative happiness in both the advertisement and the mobilization poster, though the former increasingly feels more realist than the latter. Put up decades before, the mobilization poster is faded, looking as outworn as its ideas. The glossy advertisement, in contrast, offer a glimpse of a modern lifestyle—freedom as expressed through consumerism and economic prosperity. As this novel modern fantasy is increasingly manifest in young Vietnamese city dwellers, while old nationalist signifiers fade, communist disenchantment becomes further cemented into Vietnam’s visual landscape.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Proposal for a Vietnamese Landscape #4: Wowy new pop resistance, 2007, oil on canvas.

Nguyen states that the paintings in the series attempt to “capture the conflicted visual terrain,” where the landscape reveals

a waged battle between socialist propaganda and capitalist marketing strategies … Working in media and advertising has given us a vantage point from which we can explore the strategies involved in the creation and widespread dissemination of ideas. And it’s not much different than propaganda.21

Thirty years after Đổi Mới, this juxtapositional tendency remains a popular feature of art by Vietnamese and diaspora artists. The most prominent recent example may be Vietnamese-American artist Diane Severin Nguyen’s blockbuster “IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS” (2021), the artist’s first solo institution exhibition, held at Sculpture Center in New York. The film component of the exhibition begins with an orphaned Vietnamese girl washed ashore in Poland. Years later, isolated and alone in Warsaw, she is taken in by a South Korean K-pop dance group. She later appears on-screen in a yellow shirt with red sleeves reminiscent of the Vietnamese flag. As the exhibition text elaborates, “K-pop is used by the artist as a vernacular material to trace a relationship between Eastern Europe and Asia with roots in Cold War allegiances.”22

To cast these dancers, Nguyen scoured Instagram for K-pop cover groups in Poland, where she reached out to dancers such as Jakub, a rising star and member of Majesty Dance Team. Nguyen also found the main character, Weronika (the most common Polish name), by searching “Weronika Nguyen.” The piece functions as a high-concept music video that blends disparate charged imagery and references, from the dancers’ goth sportswear clothing to the Stalinist architecture behind their sequences. At SculptureCenter, red carpet covered the floor, in a red-and-yellow color scheme that evoked the Vietnam flag. In the film, gold and red foil balloons spell out the year 1989.

At one point Weronika, after practicing dance moves in an abandoned factory, sits on a bridge overlooking a river and wonders aloud, “Where is there a beautiful surface without its terrible depth?” Weronika’s question encapsulates the postmodern sentiment of Nguyen’s approach, which strings together unlikely imagery and sources—from Britney Spears lyrics to quotes by Hannah Arendt, Édouard Glissant, Mao Zedong, and Ulrike Meinhof—through loose associative logic. In an artist talk at SculptureCenter, Nguyen explained that she was interested in thinking about the coercive image-making aspect of both communism and capitalism. The mix of disjointed symbolism—from the autotune pop songs to the dreary Soviet monuments—exemplifies post-socialist art techniques which Tan says are “employed to create a sense of irony. The past is invoked as an awkward juxtaposition of icons and cliches, so that it may be revealed as incoherent, deceptive and fragmentary.”23

Nguyen’s exhibition demonstrates the postmodernity of post-socialism, not only in the ways its decontextualized aesthetics circulate within a global economy of cultural commodification, but also in how this aesthetic generally favors the discursive over the ideological. “What emerged in the ruins of the USSR and its proteges,” Tan writes, “was the destructive glee of postmodernism, which is essentially a reaction to utopianism.”24 This destructive glee recalls what Stuart Hall described as “the postmodern argument about the implosion of the real.” But what may we conclude from the observation that there is no fixed meaning and that all realities are fragmented? To echo Hall’s concern, “there is all the difference in the world between the assertion that there is no one, final, absolute meaning—no ultimate signified, only the endlessly sliding chain of signification, and on the other hand, the assertion that meaning does not exist.”25

What Happens After the End?

“This is the end of history,” a voice-over seductively whispers in the final moments of the film from “IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS.” Following the film’s ecstatic parade of discordant mashups, this declaration evokes not only Fukuyama but Hall’s description of postmodernism as a trap, an endless present: “All you can do is be with it, immersed in it.” Though originally expressed in 1986, Hall’s cautions against nihilism bear repeating today:

You can live this as a metaphor, suggesting that certain contemporary positions and ideas are now deeply undermined, rendered increasingly fragile as it were, by having the fact of the world’s end as one of their imminent possibilities. That is a radically new historical fact and, I think, it has decentered us all.26

Post-socialist art shares postmodernist art’s aversion to ideology, equating strong belief—whether it be consumerist desire or political conviction—with indoctrination. In perpetually equating capitalism and communism as equally coercive, what is the effective thrust of post-socialist art? Per Hall, where can we go once we’ve established that the positions we’ve inherited have been deeply undermined?

Following its exhibition at SculptureCenter in 2021, If Revolution is a Sickness traveled and was reproduced for the Renaissance Society in Chicago and the Contemporary Art Museum in Houston. Like Television Commercial for Communism, these presentations were met with resounding press acclaim. Virtuosic artistry notwithstanding, the optics of such glowing reception nonetheless begs the question. What exactly does the art world, or the American art-going public, find so resonant in works that caricaturize the communist legacy?

A cynic might conjecture that post-socialist art functions as a provocative trend, as a type of Red Tourism within contemporary art. Art that’s critical of organized communism also comfortably aligns with the anti-communist liberalism that was so foundational to US modern art, a history that feels both belabored and willfully forgotten. When in 1954 the chairman of MoMA’s board, August Heckscher, declared the museum’s work “related to the struggle of freedom against tyranny,” or when Eisenhower designated MoMA as a government proxy, or when the CIA founded the Congress for Cultural Freedom, communism was at the peak of its popularity in the Soviet Union and was spreading across the Third World. This is of course no longer the situation. Post-socialist art, as Tan writes, “not only overlooks the irreducible differences between Modernist and Communist discourse, but also fails to reach a fair assessment of the Communist legacy—as both a theoretical speculation and a political entity.”27 Art that promulgates this view reduces Vietnam’s diverse revolutionary heritage to state actions. It also removes Vietnam from the context of the international development of socialism, which in many cases was integrated with the civil rights and anti-colonial movements of the global 1960s. Shih makes a compelling argument that post-socialism erases sixties-era Marxist humanism in particular, which critiqued domination in communist states from within them:

From American discussions of Marxist humanism, we can see how it was what could have linked revolutionary movements along class lines with those of gender and race. Its usefulness therefore cuts across first, second, and third worlds, across communist and capitalist blocs, and across the east and the West.28

If post-socialist critique is reductive, individual artists and curators are not the sole culprits—nor are MoMA, Guggenheim, or liberal US cultural institutions. The Communist Party of Vietnam has itself perpetuated a corrupt version of its own history, erasing vibrant internal debates and silencing opposition to state communism, whether from within a Marxist framework or against it. Post-socialist art vividly reflects the strange mutations undergone by the current Party, which has drastically departed from, yet still rides on, its communist identity. It remains important to inquire, at each instance, whether the appropriation of state-socialist aesthetics illuminates the present’s relationship with the past or obfuscates it further.

Diane Mehta, “Interview: The Propeller Group,” BOMB Magazine, February 21, 2013 →.

Mehta, “Interview: The Propeller Group.”

Mehta, “Interview: The Propeller Group.”

Minh T. N. Nguyen, Phill Wilcox, and Jake Lin, “The Good Life in Late-Socialist Asia: Aspirations, Politics, and Possibilities,” Positions 32, no. 1 (February 2024).

Jason McGrath, Postsocialist Modernity: Chinese Cinema, Literature, and Criticism in the Market Age (Stanford University Press, 2008), 13.

Arif Dirlik, “Postsocialism? Reflections on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics,” Critical Asian Studies, no. 21 (March 1989).

Shu-mei Shih, “Is the Post- in Postsocialism the Post- in Posthumanism?” Social Text, no. 30 (March 2012): 44.

Shih, “Is the Post- in Postsocialism,” 29.

Since it is a common periodization practice to treat 1989 as the onset of contemporary art, “where 1989 is the dialectical counterpart to 1945” (Peter Osborne), contemporary Vietnamese art and post-socialist Vietnamese art have great overlaps.

Mariam Lam, “Circumventing Channels: Indie Filmmaking in Post-Socialist Việt Nam and Beyond,” Glimpses of Freedom: Independent Cinema in Southeast Asia, ed. May Ingawanij and Benjamin McKay (Cornell University Press, 2012).

Mehta, “Interview: The Propeller Group.”

Nguyen Art Foundation website →.

Personal correspondence with the artist.

Personal correspondence with the artist.

Chang Tan, “Art for/of the Masses,” Third Text 26, no. 2 (2012).

Malcolm W. Browne, “First US Trade Exhibit Is Held in Hanoi,” New York Times, April 24, 1994 →.

Quoted in Pamela Corey and Nora Taylor, “Đổi Mới and the Globalization of Vietnamese Art,” Journal of Vietnamese Studies, no. 14 (February 2019).

Corey and Taylor, “Đổi Mới,” 1.

Artists in the 1990s and 2000s also distanced themselves from “art” they associated with the regime, regarding their creative activities as anti-art. See Nora Taylor, “Vietnamese Anti-Art and Anti-Vietnamese Artists,” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 2, no. 2 (Summer 2007); and Don’t Call It Art! Contemporary Art in Vietnam 1993–1999, ed. Annette Bhagwati and Veronika Radulovic (Kerber, 2022).

Nguyen, Wilcox, and Lin, “The Good Life,” 3.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, “Proposals for a Vietnamese Landscape,” tuanandrewnguyen.com →.

“Diane Severin Nguyen: IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS,” sculpture-center.org →.

Tan, “Art for/of the Masses,” 178.

Tan, “Art for/of the Masses,” 177.

Stuart Hall, “On Postmodernism and Disarticulation: An Interview with Stuart Hall by Larry Grossberg,” in S. Hall, Essential Essays, Volume 1: Foundations of Cultural Studies, ed. David Morley (Duke University Press, 2018), 229.

Hall, “On Postmodernism and Disarticulation,” 226.

Tan, “Art for/of the Masses,” 178.

Shih, “Is the Post- in Postsocialism,” 43.

Category

Subject

Thanks to Jennifer Dorothy Lee for the conversations that shaped this text, and to Hoang Minh Vu, Andreas Petrossiants, Leon Dische Becker, and Mimi Howard for feedback on earlier drafts. My gratitude also goes to Vân Đỗ and the lively audience at Á Space Experimental Arts (Hanoi) for engaging with an earlier version in presentation form.