Continued from “On Paralysis, Part 2”

1. Adulteration

The word to describe an intentional paralysis of the flow of goods through market channels is “sabotage.” It may not be the most common word today, but it was the one consistently employed by those who advocated for sabotage as a tactic in the first two decades of the term’s wider use.1 One of their key arguments was that its slowdowns and apparent accidents are not set against a regime of purely rationalized productivity and transparent efficiency. Instead, these mediated and cunning paralyses unfolded within an order of work and commerce that was itself already sabotaged and sabotaging, marked by constant adulteration, corner-cutting, and willful restriction of supply.

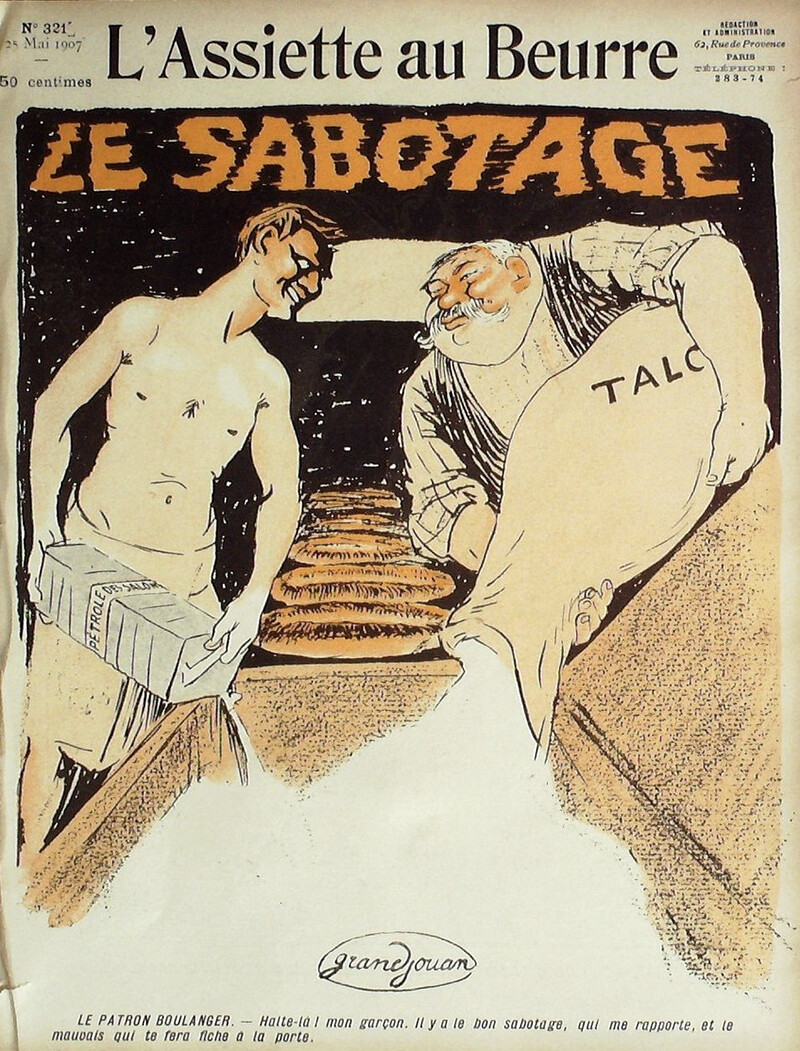

L’Assiette au Beurre, “Le Sabotage,” no. 321, 1907.

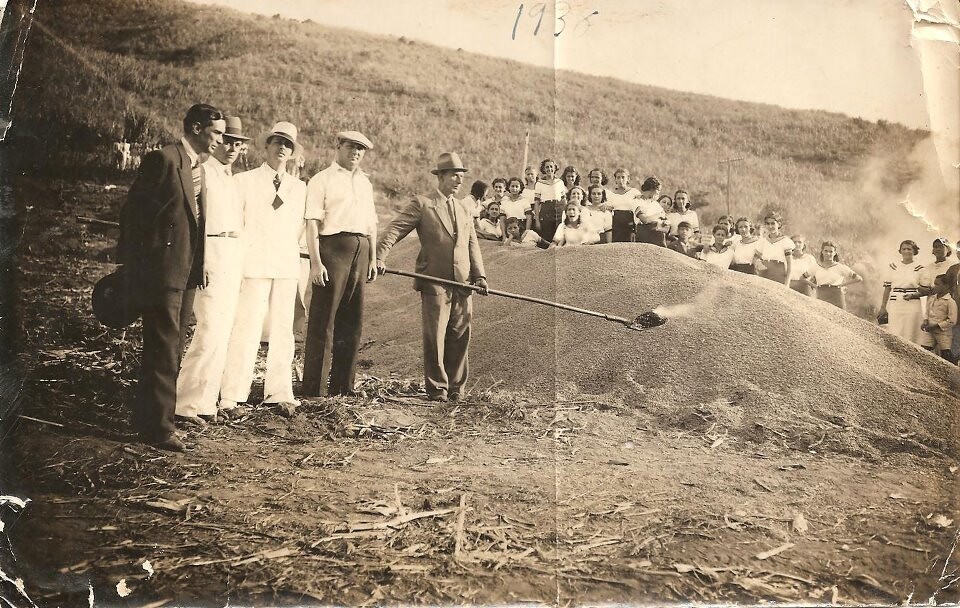

A significant part of this tendency detailed in these early accounts is the specific kind of circulatory paralysis that Joris Ivens explodes in New Earth (Nieuwe gronden), the 1934 film I discussed extensively in Part 2 of this essay. While the bulk of the film centers on the technical feat of filling in a sea in order to grow grain, its focus shifts dramatically at its end to how that grain will not reach those who need it most, because of price speculation and intentional restriction of market supply. Two decades prior to New Earth, Industrial Workers of the World militant Walker C. Smith detailed how

coffee was destroyed by the Brazilian planters; barge loads of onions were dumped overboard in California; apples are left to rot on the trees of whole orchards in Washington; and hundreds of tons of foodstuffs are held in cold storage until rendered unfit for consumption. All to raise prices.2

For her part, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn describes the way that “bananas and oranges rot on the ground” and “whole skiffs of fruits are dumped into the ocean” because “employers interfere with the quality of production, they interfere with the quantity of production, they interfere with the supply as well as with the kind of goods.” This is what she calls an “antisocial sabotage,” insofar as it “is aimed at the good of the few at the expense of the many, whereas working-class sabotage is distinctly social, it is aimed at the benefit of the many, at the expense of the few.”3 Her reference to interference with the “quality of production” is crucial for pointing to the idea of adulteration (rather than obvious destruction or restriction), the degradation or making poorer in quality by dilution or other means that is all too familiar to a social and material proletarian lifeworld rife with toxic, shoddy, and deceptive materials. Exemplary of this attention to a quotidian landscape of the cheap and poisonous is a passage by Louis Adamic unfolding a litany of accusatory questions:

If the workers, in their efforts to gain economic advantages, damaged property and destroyed materials, did not the bosses, in the interest of profits, destroy property with a ruthless and careless hand? … Did not millers and bakers mix talcum, chalk, and other cheap and harmful ingredients with flour? Did not candy manufacturers sell glucose and taffy made with vaseline, and honey made with starch and chestnut meal? Wasn’t vinegar often made of sulphuric acid? Didn’t farmers and distributors adulterate milk and butter?4

For early twentieth-century theorists of sabotage and paralysis like Flynn, “adulteration” was a crucial term serving both as a specific corporate action to be countered and as a metonym for the predatory and debilitating practices of corporations and industries more generally. Yet their interest in the term also carried a cunning possibility for a conceptual inversion whereby adulteration could be wielded as a tactic against those very practices. More specifically, these thinkers asked how sabotage could adulterate labor itself, admixing a portion of “bad work” and feigned clumsiness, introducing slipups, delays, and errors into what might appear to be business as usual, even to the close scrutiny of a boss.

Piles of coffee beans destined for destruction in 1938. Photographer unknown.

2. War and Industry

In an intriguing 1921 text, the sociologist and economist Thorstein Veblen elaborates his own argument about the bivalent ubiquity of sabotage, extensively detailing sabotage’s centrality within business management and strategy itself. He notes that the

tactics of these syndicalists, and their use of sabotage, do not differ, except in detail, from the tactics of other workmen elsewhere, or from the similar tactics of friction, obstruction, and delay habitually employed, from time to time, by both employees and employers to enforce an argument about wages and prices.5

Veblen extends this further, towards a generative flattening that views sabotage as naming “a certain system of industrial strategy or management, whether it is employed by one or another,” i.e., by those with an interest in challenging capital or those who seek to extend it. While for John Spargo, workers’ strategic use of sabotage is only destructive and suggests a forfeiture of strategy itself, in Veblen’s account the balance sheet is far from equal in terms of the damage caused to social well-being, even if he does not defend its “less amiable manifestations”:

the industrial system is deliberately handicapped6 with dissension, misdirection, and unemployment of material resources, equipment, and man power, at every turn where the statesmen or the captains of finance can touch its mechanism; all the civilized peoples are suffering privation together because their general staff of industrial experts are in this way required to take orders and submit to sabotage at the words of the statesmen and the vested interests.7

Veblen is well aware that his use of “sabotage” is at odds with how, “in American usage the word is very often taken to mean forcible obstruction, destructive tactics, industrial frightfulness, incendiarism and high explosives.”8 Yet that common usage is no accident. As he points out explicitly, it represents an ongoing and willful attempt, one “shaped chiefly by persons and newspapers who have aimed to discredit the use of sabotage by organized workmen, and have therefore laid stress on its less amiable manifestations,” displacing the meaning of sabotage from paralysis and “bad work” to more obvious forms of damage, destruction, maiming, and violence.9 This attempt unfolds on two fronts I’ve already suggested as central to the trope of paralysis more broadly, that of war and of industry.10

“Industry” as a frame of meaning is obviously relevant from the beginning of sabotage as a political (and anti-political) idea, given the way its earliest advocates conceptualized it as a form of “working badly”: adulterating the rate and quality of one’s labor by introducing unannounced stoppages, lags, errors, and apparent accidents (that employers cannot prove to be otherwise) into the chain of production and circulation. This close link is understandable given the absolute focus on efficiency that marks management thinking—Taylorism, the Gilbreths’ time and motion studies, and factory organization more broadly—during the very years that sabotage emerges as a term and tactic. And it also furnishes some of the most evocative images of acts of physical sabotage, like hiding glass soda bottles inside the engines of cars as they roll through the assembly line. However, the close bond of sabotage to industrial production, as well as other forms of heavily technical waged work, can lead to an excess focus on certain kinds of work, particularly those that appear manual and mechanical, and whose forms of tactical paralysis also have the sort of drastic, suddenly halted clarity to them that fits too cleanly along the breakdown/insight pairing I detailed in the first two installments of this essay.

In addition, the idea of sabotage was also transformed by the specific way its opponents demonized it in the first two decades of the twentieth century, canceling out much of the subtlety and potent unreadability or uncertainty crucial for its theorists and advocates, including within industrial contexts. Such critique happened along two closely related lines. First, as Veblen himself notes, it came to be defined above all as an act of destruction, committing violence against an employer’s factory, vehicles, spaces, or crops. This is despite the fact that nearly all its early advocates put continual stress on the fact that sabotage was not about destruction but about a negation that “destroyed” only efficiency, whether by adulterating the time of labor by working slowly or sloppily, by producing commodities that were visibly too poor for sale, by slowing the circulation of goods, or by temporarily disabling the means of work. In short, it is a tactic of paralysis that introduces friction, latency, and threat into the transformation of capital into commodities and back again.

The accusations stuck, and even prior to furnishing the language subsequently used in law to criminalize radicals, they came from other leftists like Spargo, who did the work for the state by laying this ground. In article after article, and in a heap of books, socialists and more reformist labor organizations did their damnedest to cast potential saboteurs or advocates out of socialism and into anarchism—horrors!—and to neutralize sabotage’s unreadable agency by reducing it to simple damage.11 For a single instance among too many, consider James Boyle’s definition of sabotage, published in 1913 (early in a decade that will only amplify this further). Gone is any sense of paralysis, replaced with “damage” and “destruction” in what he sees as the anarcho-disaster of syndicalism:

“sabotage”—that is, damage to and the destruction of machinery and the means of production and distribution, including such damage to plants as will prevent the operation of what are classed as “public utilities”; and any means to interfere with the process of production and transportation.12

As for the military mode, that meaning of sabotage and its paralyses also came quickly. Barely a decade and a half after sabotage was first explicitly posed in the political milieu of French anarcho-syndicalism, the term in English comes to be used regarding the First World War. To be sure, the trope of war is already present in the language of sabotage’s first advocates, where it appears as a specific operation within class war. In Émile Pouget’s foundational text, sabotage is gathered under the sign of the “guerrilla”: “This execration of the regular armies for the guerrillas does not surprise us, neither we are [sic] astonished at the horror capitalists express for sabotage. In truth sabotage is to the social war what guerrillas are to national wars.”13 And in the introduction to Pouget’s book by Arturo Giovannitti, who not only frames Pouget’s theory for an (anti-)American readership but also brilliantly develops it himself, we can find the figure of espionage, as “the saboteur … [operates] exactly like a spy in disguise in the camp of the enemy.”14

Palestine Railways H3 class 4-6-4T steam locomotive (converted from a WWI Baldwin 4-6-0) and freight train on the Jaffa and Jerusalem line after being sabotaged by Zionist terrorists, 1946. License: CC0.

However, the term quickly disseminates beyond the orbit of their readers as a term both slangy and technical, and in the context of mass warfare, it comes to designate actions like when a railway is blown apart, a battleship sitting in harbor has a hole blown in its hull from divers below, or telegraph cables are cut. In other words, it starts to locate, in both a legally codified and widely disseminated way, the idea of sabotage within the clarity of a visible act that results in explicit destruction or permanent damage. Moreover, these are attacks that also can be bound to specific actors, to saboteurs and special agents who carry them out indeed unseen yet who remain available to become alternately celebrated or demonized, as brave avant-garde fighters or nefarious agents of an enemy that refuse to fight fair, depending entirely from which side the attack comes.15 In the same years when the US state will define sabotage in a labor context through anti-sedition laws as destruction of property, it will also by 1920 criminalize (in US Code § 2153, “Destruction of war material, war premises, or war utilities”) whoever “willfully injures, destroys, contaminates or infects, or attempts to so injure, destroy, contaminate or infect any war material, war premises, or war utilities” with the “intent to injure, interfere with, or obstruct the United States or any associate nation in preparing for or carrying on the war or defense activities.”16 And while that code itself won’t formally gain the word “sabotage” until mid-century, this did not stop newspapers from referring to it at the time as the “sabotage act.”

Obviously, those instances of military sabotage, or attacks on the means of war-making, are real. Especially in the context of insurgent and anti-colonial battles, they were often acts of cunning and ingenuity, activating technical materials, perceptual expectations, tightly coupled systems, and the latent properties of landscapes in order to produce profound effects. (For all the instances of dynamiting the track or the bridge, there are subtler and stranger moments throughout these scattered histories, from moving stones to encourage a stream to wash away a supply road to filling a dead rat with plastic explosives so that it “might be shoveled into [a boiler or furnace] for disposal.”17) Nevertheless, the primary effect of the capture of sabotage by this military context is to bind its meaning closely to those disabling attacks on infrastructure, armaments, or sites.

Two key points follow. First, and more obviously, this feeds into that tendency by states and reformist parties/thinkers to actively misdefine what any of sabotage’s early theorists had proposed, dislocating it from the complex and messy realm of bad work and into the legal space of violence against property. Once sabotage gets increasingly defined as an act of war, it’s a small step to insist that it is not only fundamentally violent but also that it never belonged within the language or sphere of politics: it becomes the sneaky, individual act that refuses to negotiate, vote, or discuss, and instead insists on war. (Again, no disagreement here from most of its advocates, who welcome the exit from the charade of representational politics.) Second, insofar as the core of that misdefined meaning hinges on infrastructural damage and interruptions to supply chains or lines of communication, “sabotage” becomes more broadly a word used to speak of almost any warfare that does not take the form of openly firing upon soldiers or enemy positions. Yet, as has become atrociously clear in the debilitation of necessary services and infrastructures that formed the decades-long backdrop to Israel’s current genocidal assault on Gaza, contemporary warfare enacted by sovereign states consists largely of precisely these forms of irregular and unofficial war. In other words, from our cursed vantage point, with its extensive tactical emphasis on paralysis and debilitation through aerial campaigns and cyberattacks, sabotage starts to show itself not to be war’s disavowed underside so much as its leading edge.

What, then, is the consequence of framing sabotage within the logic of industry and war? On one side, sabotage gets narrowly defined in terms of that more directly visible (and blamable) act of damage or destruction, rather than its uneven paralyses, hitches, and adulterations. Simultaneously, however, it also becomes identified as the acute symptom of mistaken and individualistic political tendencies that run counter to the supposedly correct direction for collective action, whether nationalistic war or class struggle itself. In this way, sabotage comes to exemplify and stand in as the name for the extra-political mode marked more broadly by the trope of paralysis. In the decades to follow, it will be read repeatedly as the sign of a selfish, sneaky, and destructive subjectivity, one that will not be allowed even by a socialist politics that sought to be a militant counter to capital’s organization of the world.

3. The Inhuman

The framing of sabotage within the martial and industrial context has also led to significant restrictions in what it could mean, both because of excess emphasis on destruction and on the way that it has overshadowed forms of labor, domination, and resistance that don’t align so easily with more familiar figurations of the waged male worker or the soldier. However, there is an aspect that remains crucial in both registers and that comes close to naming what’s so distinct about the mutually determining relation of sabotage and paralysis. This is a particular understanding of technique and technicity, and more specifically of a mode of human engagement that eschews traditional politics in favor of routing itself through (and thereby becoming almost indistinguishable from) the normal operations of a machine, system, process, or space. Less abstractly, we can think of how acts of sabotage are able to remain both undetectable and disarming because they engender paralyses without any immediately provable person behind them: the server can crash because someone “accidentally” (but intentionally) overloaded the power supply, but it also can crash because drawing that much continual energy into circuits within an overheated room means that breakdowns will inevitably happen.18 Taken together, the attacks on sabotage for eschewing accepted modes of representational and organized political participation were largely meant to discredit it as a tactic, yet those condemnations also got something right. Sabotage does flaunt those conventions and requirements, and in place of them, it articulates itself in a language we might call inhuman.

If sabotage is a language, it is a purely negative one. It does not offer its own signs, it does not put forward something uniquely its own, and, if successful, it cannot be traced back to a legible “speaker” or author. Sabotage can produce startling occasions and possibilities, surreal images of implausible novelty and almost comic inversion, like the entire orchard of fruit trees planted upside down, their bared roots waving to the sky. However, it proceeds only in the terms of an already established process, structure, or system, because if it didn’t, it couldn’t dwell in the space of unprovable doubt to remain always potentially an accident, just a tired and poor performance on the job that day. Within those terms, sabotage shows itself only in relation to expected functions, appearing as latency or stoppage. It appears as what does not happen, does not get transmitted, does not get completed, and does not respond, forming a syntax of stutters, lags, and interruptions, a dissipated rhythm of paralyses.19

To speak of this as “inhuman” is not to name all the nonhuman parts of these spaces or processes that can get activated. Rather, it is to think about the specific relations and frictions that gather in the circuits and interactions between humans, materials, machinery, weather, and other forms of life when they are yoked together in the reproduction of capital. Part of what is genuinely radical about sabotage is how it materially and tactically seizes on those interactions and connections between the animate and the inanimate alike. Rather than continually diverting potential agency into forms and languages much more commonly understood as political, like a slogan or a march, sabotage takes within those inhuman networks. Admitting that the game is already rigged and there is no fair fight to be had, it splits away from the narrowed channels of the expected and allowable and into the terrain of the possible. And from this, it shows that when one’s capacity is dislocated from a knowable, identifiable, predictable, and legally targetable entity, it gains tremendously in force.

Kidult tags Balenciaga’s Paris Flagship with “Merry Crisis.” 2019.

This expansion of possible action, while masking one’s culpability, is what leads states to scramble to legally define and criminalize sabotage. It’s also what caused leading critics of such tactics like Spargo to not only disavow it but to rightly understand it as coming from and articulating an “anti-political” position, as he explicitly describes the Wobblies (and their open mockery of the idea that revolutionaries should obey bourgeois laws or accede to the procedures of representational politics). As I’ve suggested earlier, we’d be right to detect in this a different kind of rejection, one closer to incompatibility, unthinkability, and even disgust. This has everything to do with those chains of paralysis that span organisms, machines, materials, and spaces, and that show the deep links of circulation and transmission already active between them. It has to do with the ways that thinkers of paralysis (like the Wobblies) spoke of and against a lived world of adulteration, denigration, and abjection in which workers were seen to be as cheap and replaceable as the inanimate tools they worked with. And perhaps most of all, it has to do with how, in the face of this, both workers and those excluded from formal work articulated forms of struggle that did not seek purity or exodus from those chains. Instead, they moved in and through them, passing through the material bonds formed by the very processes of labor, exploitation, and domination they wanted to ruin.

I want to return here to that dramatic phrase of Spargo’s: “This social cataclysm is to take the form of the General Strike, when the proletariat paralyzes society by becoming motionless.”20 In his phrasing, we can feel that trace of disgust, a certain sneering affect in excess of his insistence that paralysis-oriented tactics will be a political disaster, or a dishonorable threat to civil society at large. The sneer gathers around the word “motionless,” which isn’t a one-off in his writing. Nine pages later in the same book, we find another iteration of the same claim: “Labor needs but to fold its arms and become inactive in order to terrorize the world. In a single sentence we have a graphic portrayal of a world paralyzed, not by insurrection and bloody revolt, but by the non-action of the producing masses.”21 Here is that same mimetic contagiousness ascribed to paralysis, but as a fixation on a willful self-paralysis. What he describes is an anti-political action that is neither insurgent nor revolutionary. It takes instead takes the form of “non-action,” becoming “motionless” and “inactive.” One becomes like an object, the very obstinate middle that holds up processes and blocks the relays.

In short, this action disables by disabling itself, and the way it reveals an ableist imaginary that hinges on the image of the healthy, active, publicly present, legible citizen-worker is unmistakable. If paralysis as a trope cannot be reduced to a mere stand-in for physical paralysis, as I’ve argued, the unease produced by paralysis as a willful tactic turns out to rest heavily on the figure of the paralyzed person and on long histories of social exclusion and disgust. This is hardly exceptional. It is instead yet another example of just how central putatively normal perception, mobility, and “action” are for the basic contours of a public politics: the promise and demand of using your voice, of standing up and being seen and counted, of being consistently coherent, audible, legible, and sane. The promise of the “upstanding citizen” is posed against the figure of the cripple, etymologically bound to the one who creeps, who stays low, to the one who is not proud and erect and in public view.22 In this way, that figure—along with the hobbled, the mute, the blind, the mad, the deaf, the chronic, and, of course, the paralyzed—becomes the exemplary negative definition. Construed as unable to “stand on their own two feet,” to be autonomous, or to exist without networks of support and collaboration that exceed them, the one understood as paralyzed, inactive, and motionless comes to abjectly stand in for what cannot be allowed in the realm of the political—including for those forms of tactical “non-action” that produce real effects in the world, chaining out and out.

4. Unavoidable Delay

When a person is paralyzed, in whatever way, they are shadowed by a dense overlay of social and cultural tropes that extend far beyond what is or is not conventionally political. This takes place on a practical and often daily level, given how the frequent employment of paralysis as a casual figure of speech risks drastically dismissing the lived experiences of those with paralyzing impairments and occluding actual forms of privation, lack of adequate support, and denigration.23 Moreover, the persistence of cultural imaginaries of paralysis generates significant consequences in terms of shaping what will be seen as socially possible or acceptable, including in the laws and policies that buttress those judgments. Think, for instance, of the recurrent cultural coding of a person with some form of highly visible paralysis as alternately evil or “twisted,” or as radically desexualized, infantile, or pitiable.24 For such a figure, the only culturally sanctioned options are to be hidden from public life or recuperated by the fantasy of rehabilitation, the “supercrip” who performs beyond normality itself as an “inspiration.”25

That promise of rehabilitation signals more than just a de-paralyzing fantasy of return to previous levels of mobility that aligns easily with ableist conceptions of normal function and health. Unsurprisingly, such a promise is also grounded in the specific idea of a return to work, hinging on the ongoing valuation, or the abject devaluation, of an individual’s relation to economic productivity. The density of these bonds between disability and work can hardly be stressed enough, as is evident from how in many countries, such as the United States, to “go on disability”—i.e., receive state support—requires being judged unable to perform waged labor.26 Moreover, that very idea of “disability” itself does not exist separately from the relations of capital. As Marta Russel and Ravi Malhotra sharply frame it, “disability is a socially-created category derived from labor relations, a product of the exploitative economic structure of capitalist society: one which creates (and then oppresses) the so-called ‘disabled’ body as one of the conditions that allow the capitalist class to accumulate wealth.”27 Again, though, it’s crucial to refuse any easy sense of a preexisting and stable ideology of work that sorts and casts out those who are impaired and labels them as disabled and unproductive. The relationship is nearly the opposite. Ideas about work are constituted around—and honed through trying to manage, neutralize, and profit from—debilitation, while the kinds of work continually shaped by those very ideas are themselves often physically debilitating.

This is true of many of the histories in which paralysis is so deeply entangled, all of which involve situations that are not only compared to paralysis or understood through it, but that also hinge on a density of quite literally paralyzing activities.28 War, and the ongoing martial operations, testing, and training that happen throughout nominal “peacetime,” makes this especially explicit. The centrality of paralysis as an idea with which to theorize about what strategic air power can do to enemy infrastructure leads to actual bombing campaigns that kill and maim, in ways that materially enact those hellish homologies between humans and energy networks.29 But this feedback between the idea of paralysis and the system of paralyzing activities is equally central to histories of capitalist production and reproduction. For instance, regimes of work discipline, industrial rhythm, and pressure were consistently generative of physical paralyses, as well as of paralyzing tactics such as sabotage used to disrupt those regimes. As historians like Anson Rabinbach, Karin Bijsterveld, and Michael Rosenow have lucidly extended, we shouldn’t discount the political force of reckoning with workplace accidents or debilitation through slow and ongoing daily activities, chemical exposures, and repeated tasks, including informal and relatively unmechanized kinds of labor central to contemporary industries, such as mining.30 In addition, much like Mara Mills has shown with regard to the dynamics of deafening, and the uses made of Deaf persons, within histories of telephonic technologies those who were paralyzed or otherwise debilitated were not de facto ejected from laboring, but were instead central to how labor would be transformed.31

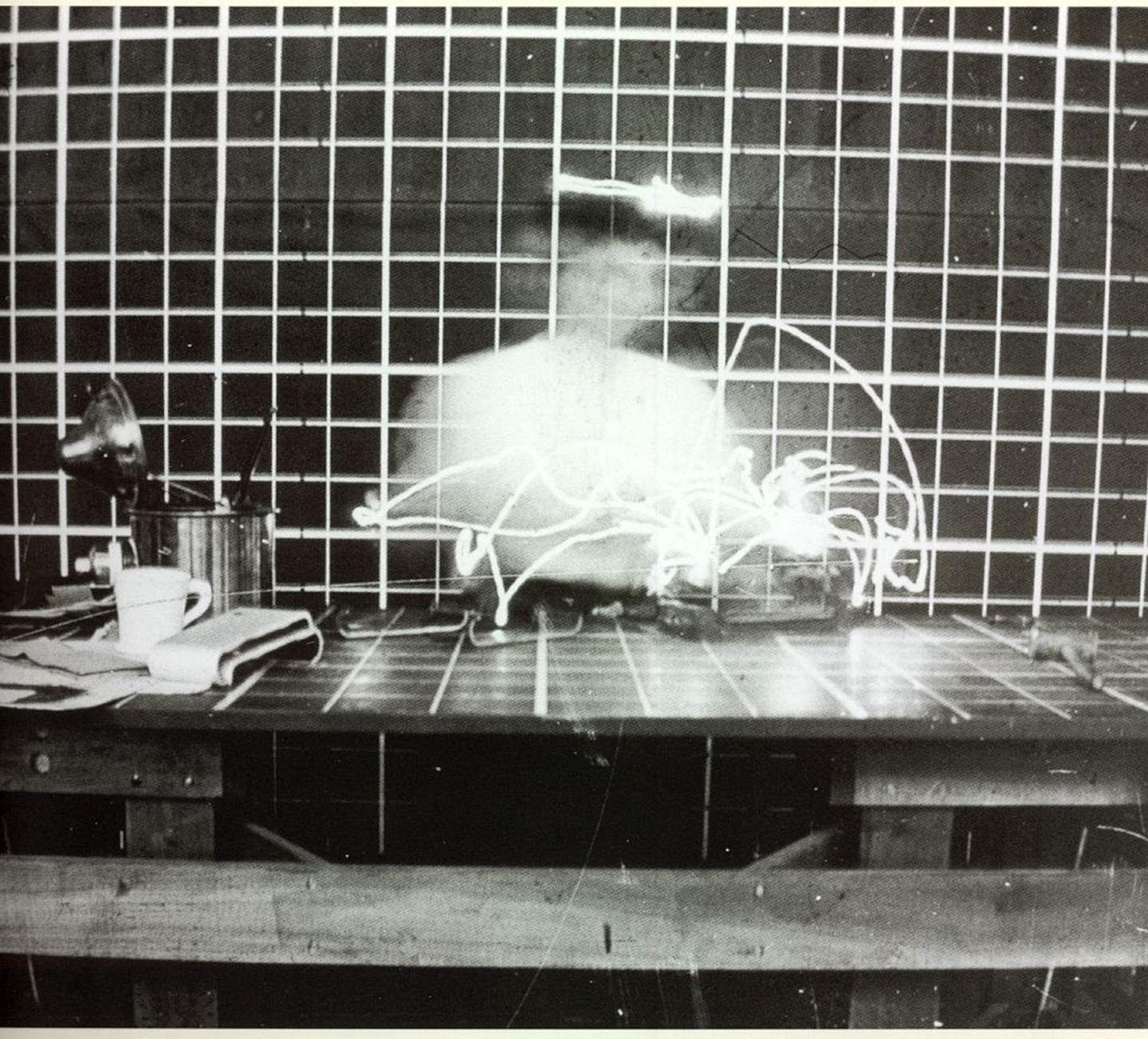

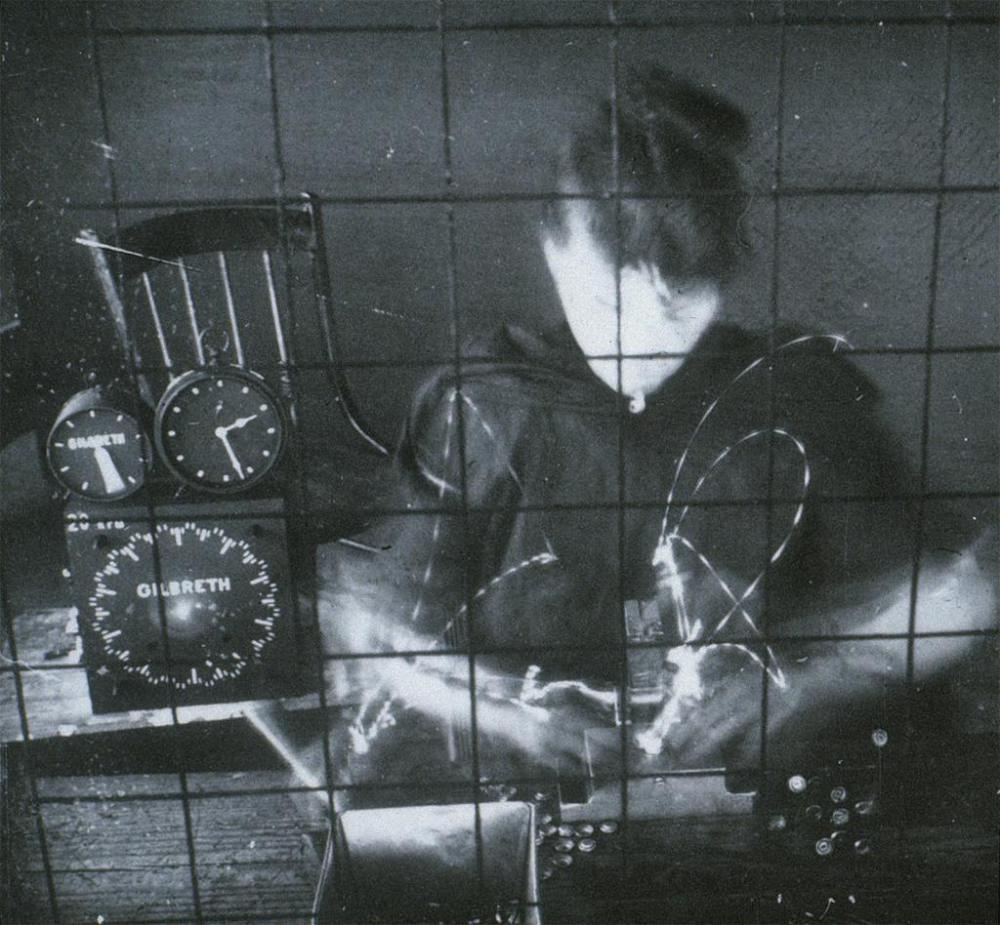

A time-motion study by Frank Bunker Gilbreth and Lillian Gilbreth from the early twentieth century.

We can find this dynamic in especially dramatic form in the influential work of early twentieth-century “scientific management” theorists Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, known both for their time and motion studies of labor processes and for their only-somewhat-tongue-in-cheek application of those principles to streamlining family life, detailed by two of their children in the book Cheaper by the Dozen. In both their practices and writings, the Gilbreths are relentlessly devoted to the reduction of inefficiency in labor to save energy, reduce unnecessary fatigue, and, above all, neutralize the fundamental “waste” of effort and time hidden within every human movement, particularly when at work. According to Frank and Lillian, “there is no waste of any kind in the world that equals the waste from needless, ill-directed, and ineffective motions, and their resulting unnecessary fatigue.”32 The battle against this “waste” gets posed as a civilizational battle stretching back across human history, only now conquerable with modern means, yet theirs is also a project with explicitly nationalist overtones that can be strategically couched to suit a war economy and a desire for American imperial hegemony. The solution they propose is a total analytical dissection of labor processes, breaking single tasks into discrete parts to detect the little gaps in time that could be closed. Such minute lags and “micromotions” will necessarily get missed without the tools the Gilbreths turn to, like moving picture cameras—turned to face workers with chronometers in front of the lens and reticular grids on the wall behind for scale—and a “chronocyclegraph,” which allowed them to zoom in on a single gesture to see its tiny deviations and wasted movements frame by frame.33 In their methodology, delays and breakdowns take a form almost directly counter to simple malingering or the kind of willful self-stasis that Spargo denounced. Rather, what causes the inefficiency that the Gilbreths target is too much movement, an excess of animacy and motions that need not be done to complete a task, resulting in unnecessary fatigue and wasted opportunities for profit.

Yet at the heart of this, there is one figure seen to most embody this “wasted” energy and time in full—not in a specific action, badly choreographed task, or laziness, but in their entire being. This is what they designated as the “cripple,” and especially those American soldiers who were wounded in World War I. “What,” the Gilbreths ask, “is to be done with these millions of cripples, when their injuries have been remedied as far as possible, and when they are obliged to become again a part of the working community?”34 The solution they provide, unsurprisingly, will make use of the same analytical tools they deploy elsewhere, albeit with the difference of trying to develop prescribed movements that might be adequate to bodies with a restricted range of motion. In this way, the Gilbreths aim to conquer paralysis, and to do so by a prosthetic joining, binding an impaired body to a mechanical process that allows it to achieve speed and mobility, and, in the process, “to inspire the cripple with the feeling that he can remain, or become, a productive member of the community.”35

The “cripple” therefore emblematizes the waste of America’s “human resources” for the Gilbreths.36 It manifests a physical limit—the body that is conventionally seen to be unable to do productive work—but also a political one that they cannot even fathom, or at least allow publicly: the idea that anyone might challenge either the supposed utility of this frenzy of streamlined work or the very category of what constitutes “waste” itself. For the Gilbreths, the “elimination of waste” is not merely a project of capital. It is a civilization-scale undertaking that benefits all involved in the process: “All workers are sharing in the savings made possible by the elimination of waste.”37 Yet the counter to this is the dizzying quantity of waste produced by the logic of competition between firms, as well as the wasting of what has been produced, both through the irrationalities of the market and the kinds of willfully orchestrated “antisocial sabotage” that Joris Ivens detailed with lucid fury. So, in an obscene extension of what the Gilbreths saw at every workstation, this excess motion of the circulation of capital itself is what becomes glut first, then paralysis. It brings about a crisis of overaccumulation in which circulation chokes on itself, leaving people starving while food sits and rots in the warehouses, until it is set ablaze in the fields where it was harvested and where ocean waves used to roll.

What we see in the Gilbreths’ motion studies is the proper challenge to sabotage. It is not mere surveillance, increased policing, or something that openly oppresses and invites a revolt. Instead, it is a mode of management and control that seeks to saturate every step of the process, all the while insisting that what’s good for profit is good for those whose stolen time generates that profit. Nothing spells out this effort so starkly as the collection of “therbligs” (“Gilbreth” spelled backwards, albeit with the h and t swapped)—symbols invented to visually code any process or action, allowing it to be broken down into its smallest constitutive elements or movements. Most of these are abstracted but iconic representations of a part of a body in the midst of these activities, like “Search” and “Find,” which involve the abstracted outline of a human eye looking to the side in the former and straight ahead in the latter, as if having scanned the room and located its target.38 In four of them, however, we get a minimal representation of an entire human form, with a pseudo–stick figure consisting of a circle for a head, a line for a body, and a ninety-degree bend to make feet. In “Plan,” a crooked angle appears to suggest an arm and hand that scratches the chin, Rodin’s Thinker in glyph form. Unlike the signs that represent eyes and hands, however, the minimally represented body doesn’t mark a specific physical action. Instead, it designates the threshold where the project of scientific management falters, where a potentially distributed inefficiency, woven into every unnecessary motion, instead becomes a complete stop, the worker halting their demanded actions entirely.

“Rest for Overcoming Fatigue” depicts a body at reasonable seated repose, as if during a sanctioned break. And while systems of scientific management like that of the Gilbreths will seek to minimize fatigue, it also treats this rest as an expected input, even if never acknowledging how newly exhausting the relentless machinic pace will become after all the temporal fat gets cut from repeated gestures. “Avoidable Delay” suggests a delay caused by the worker themself (from a hand doing nothing while the other moves to a tool broken by poor handling) that could be avoided with proper training and motivation, shown by a stick body on its back, as if napping or staring at the clouds or factory ceiling, smoking a cigarette and killing time while on the clock. (On the therblig chart, it is described as “Man lying down on job voluntarily.”) “Unavoidable Delay,” conversely, suggests an involuntary pause caused by factors beyond the worker’s control. In some instances, the suggestion is that the working process has itself not yet been rationalized. In a photographic series meant to show the gestures corresponding to the therbligs, a worker takes the cap off a mechanical pencil to check the quality of the eraser: “The right hand is idle—there is nothing for it to do. Therefore this delay is unavoidable.”39 In others, it indicates something on a larger scale, like a disruption elsewhere in the production process that prevents the task from being achieved.

A different and unacknowledged meaning is at play here, manifest in the choice of the sign itself. It doesn’t resemble what we might expect, like a machinist taking a seat while waiting for the lathe to get spinning again. Instead, we see a body bent sharply at the waist, head hanging down or even striking the floor. (Indeed, the official explanatory description in the table of therbligs is “a man bumping his nose, unintentionally.”)40 This looks less like a pause in which one rests than the unavoidability of a body pushed too far, too long, and too fast, left unable to be upright and now exhausted, or puking or spasming. We can’t quite say. We can only know that we are dealing with a system in which motions might be rationalized, but the rationale for their motivations can never be questioned, making this debilitation and collapse “unavoidable”—not unlike money from a heist that could have been used to support a bent body, but will be burnt instead.

The challenge for sabotage will be to erode the gap between unavoidable delay and avoidable delay, to make avoidable delays appear unavoidable, both as a threat to employers who pay poor wages and to enable the kind of unprovability that sabotage hinges on and weaponizes. (Did the power just happen to go out, causing everything to go quiet? Or did someone knock it out?) The tactic will try, again and again, to pass resistance and fatigue out from an individual body expected to work faster, more repetitively, or for less money, back into the system of production and circulation itself.41 Conversely, management strategies and work protocols across the twentieth century seek to counter this tactic by minimizing possible deviations. Still, it’s worth noting that even internal to the Gilbreths’ own processes of analysis and documentation, they were unable to ward off that creep of friction, exhaustion, and unpredictability. Across their tremendous volume of film minutely detailing these tasks, a hand-cranked 35 mm camera was used, which means that the rate of speed that the frames advance through the camera could not be constant, no matter how smoothly the operator tried to crank. In this way, even in the documentation of measures designed to minimize fatigue, that fatigue still creeps back in, in how the filmed motions speed up and slow down erratically when the one who films and turns the crank eventually tires, losing their rhythm and failing to be as mechanically regular as the device they operate. Yes, you can place a chronometer in the scene to record the passage of time faithfully for each frame, and then try to precisely locate the passage of a hand through the air at every stepped microsecond of its arc or tremor. But when we watch the film play back, the unregulated pace of the cranking hand behind the camera makes itself felt on screen, and the clock’s dial staggers its path around the clock, as though drunk and reeling.

To be continued in “On Paralysis, Part 4”

After the term was more explicitly posed as a political tactic by French anarcho-syndicalists in the late 1890s (and formally declared at a Confederation General du Travail congress in 1897). See “Reading Between Enemy Lines” in my forthcoming book Inhuman Resources (Sternberg Press, 2025) for a brief sketch of the overall trajectory of sabotage as an idea.

Walker C. Smith, Sabotage: Its History, Philosophy & Function, 1913 pamphlet published by Industrial Workers of the World →. Fantasies of government oversight aside, this is by no means just in the past. Timothy Mitchell’s Carbon Democracy details this on the level of the planned restriction of the circulation of oil, while we can find extremely recent instances of a level of food destruction that easily belongs in New Earth. See for instance this report on food destruction during the Covid pandemic: David Yaffe-Bellany and Michael Corkery, “Dumped Milk, Smashed Eggs, Plowed Vegetables: Food Waste of the Pandemic,” New York Times, April 11, 2020 →.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Sabotage: The Conscious Withdrawal of the Worker’s Industrial Efficiency (IWW Publishing Bureau, 1916), 5.

Louis Adamic, Dynamite: The Story of Class Violence in America (Viking Press, 1934), 373. Another account of adulteration can be found in Smith: “The doctor gives ‘bread-pills’ or other harmless concoctions in cases where the symptoms are puzzling. The builder uses poorer material than demanded in the specifications. The manufacturer adulterates foodstuffs and clothing. All these are for the purpose of gaining more profits.” Smith, Sabotage, 66.

Thorstein Veblen, The Engineers and the Price System (Batoche Books, 2001), 5.

His use of the term “handicap” here is worth noting given the concerns of this essay and the fact that it is in the early twentieth century that we see a shift in its meaning to refer increasingly to bodily impairment rather than adjusting the odds of a bet.

Veblen, The Engineers and the Price System, 55.

Veblen, The Engineers and the Price System, 5.

His attention to this dynamic is important, given that he was watching the shifts in the word’s meaning in real time, in the late 1910s and early 1920s.

I am here using “industry” as shorthand for sectors of waged work historically associated with “productive” and often masculine-coded labors of manufacturing, extraction, or the circulation of commodities.

Indeed, that strange unreadable/unprovable quality remains in such critiques almost solely as the sign of sneakiness and cowardice, of not fighting fair and out in the open. Of course, its advocates wouldn’t disagree that it does not come out into the open. Almost all early theorizations of sabotage make explicit how this ability to “strike on the job” and to tune the production/circulation process against itself, rather than coming out into public view or representational politics, is precisely the point and strength of sabotage.

James Boyle, The Minimum Wage and Syndicalism: An Independent Survey of the Two Latest Movements Affecting American Labor (Stewart & Kidd Company, 1913), 91.

Émile Pouget, Sabotage, trans. and introduced by Arturo Giovannitti (Charles H. Kerr and Company, 1912), 75.

Arturo Giovannitti, introduction to Pouget, Sabotage, 33.

We should also note how much the logic of sabotage has often been aligned with, and advocated by, those who refuse these sides, who refuse the naturalization and binarism of war that sends proletarians to murder each other under the sign of national necessity. Consider Joe Hill, for instance, the Wobbly songwriter and militant executed by the state on a false murder charge. Hill wrote of sabotage in a brilliant 1914 essay on “HOW TO MAKE WORK FOR THE UNEMPLOYED” (i.e., by “striking on the job” and slowing up production so as to make everything take longer and require more hours or more laborers). In that essay he writes, “This weapon is without expense to the working class and if intelligently and systematically used, it will not only reduce the profits of the exploiters, but also create more work for the wage earners.” But in an acerbic letter not two weeks before he was set to be killed, he also attacked the ground of national chauvinism and wrote that “war certainly shows up the capitalist system in the right light. Millions of men are employed at making ships and others are hired to sink them. Scientific management, eh, wot? As far as I can see, it doesn’t make much difference which side wins, but I hope that one side will win, because a draw would only mean another war in a year or two.” That said, in a turn with a graveside humor only appropriate for his looming execution, and marked by a tone somewhere between sarcasm and deadly seriousness that characterizes many of his letters, he mocks those “silly priests and old maid sewing circles that are moaning about peace” and suggests instead that the “war is the finest training school for rebels in the world and for anti-militarists as well.” Joe Hill, “Letter from Utah State Prison,” September 9, 1915, in Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology, ed. Joyce L. Kornbluh (PM Press and the Charles H. Kerr Library), 152.

See →.

Indeed, this is not an imaginative turn of phrase: it is an explicit part of the eminently weird tactics of British Special Executive Operations agents: “Dead rats filled with PE were prepared by taxidermists; they incorporated a Mk I11 oz guncotton primer, a short length of time fuse, and a No. 10 time pencil. The idea was that a dead rat left near a boiler or furnace might be shoveled into it for disposal. In that case no activation of the delay fusing was necessary, but it could also be activated and left where it would inflict damage.” Gordon Rottman, World War II Allied Sabotage Devices and Booby Traps (Bloomsbury, 2006), 52.

See my essay “Acid Doubt” at Triple Canopy for a longer articulation of this argument →.

As I examined earlier, one possibility of this is an increased capacity to recognize the kinds of links and circuits that were already in place and already organizing the world, even if the trope of breakdown/insight often too easily assumes that a critical or radical knowledge flows from this.

John Spargo, Syndicalism, Industrial Unionism and Socialism (B. W. Huebsch, 1913), 85. I would put Spargo’s reckoning with this in dialogue with another enemy of insurrection so to speak, Carl Schmitt, whose reading of class politics in The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy also captures a crucial aspect of what I’d consider a collective and intentional self-inhumanization that has been anathema to more mainstream socialist or labor politics for much of the last century and a half. Schmitt writes that in the process of revolutionary organizing and a communist horizon, “the proletariat can only be defined as the social class that no longer participates in profit, that owns nothing, that knows no ties to family or fatherland, and so forth. The proletarian becomes the social nonentity. It must also be true that the proletarian, in contrast to the bourgeois, is nothing but a person. From this it follows with dialectic necessity that in the period of transition he can be nothing but a member of his class; that is, he must realize himself precisely in something that is the contradiction of humanity—in the class.” As for Spargo, for Schmitt this is a situation to be avoided. Carl Schmitt, The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (MIT Press, 1988), 62.

Spargo, Syndicalism, 94. And again: “What the Syndicalist has in mind is that the workers by becoming inactive, ‘motionless,’ destroy the entire structure of capitalism and create for themselves both the opportunity and the necessity for establishing a new social and industrial order” (91).

Crucial texts on this question include Joanna Hedva’s “Sick Woman Theory” (available online at →) and the reading of flexibility in Robert McRuer’s Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (NYU Press, 2006), via Emily Martin’s work on neoliberalism.

See, for instance, Martin Sullivan’s “Subjected Bodies: Paraplegia, Rehabilitation, and the Politics of Movement” for not only a reckoning these forms of denigration, but also for his account of the production of a paraplegic subject position/subjectivity. In Foucault and the Government of Disability, ed. Shelley Tremain (University of Michigan Press, 2015).

In this way, these kinds of figurations can’t be reduced to a single kind of genre, as they are as common in horror as they are in supposedly feel-good stories of persistence.

See Amanda K. Booker, “Docile Bodies, Supercrips, and the Plays of Prosthetics,” in “Disability Studies in Feminist Bioethics,” special issue, International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics 3, no. 2 (Fall 2010); and Sami Schalk, “Reevaluating the Supercrip,” Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 10, no. 1 (2016).

This is a fact that produces genuine crises for people trying to get by, a sort of hinterland of never having enough and yet being trapped by the very mechanisms that allegedly support: the stipend is often too little, especially if more intensive regimes of care or medication are needed, and yet doing any waged work whatsoever disqualifies them from that support in full.

Marta Russel and Ravi Malhotra, “Capitalism and Disability,” Socialist Register, no. 38 (2002), 212.

I won’t pursue it here, but see my essay “Down to the Bone” in Inhuman Resources (forthcoming from Sternberg Press, 2024) for a discussion of the relation between psychoanalysis, PTSD, and “railway spine,” i.e., forms of often paralyzing injuries generated by the expansion of railway networks into urban areas. I also return to this in the final installment of this series, in terms of deaths and maiming caused by trains.

The framework that Jasbir K. Puar advanced around this is vital, especially in terms of thinking towards debility, rather than disability per se, as it attends to the violence done to people in ongoing and geopolitically normalized regimes of harm and debilitation that precisely elude becoming identifiable as disability. See Jasbir K. Puar, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability (Duke University Press, 2017).

Anson Rabinbach, “Social Knowledge and the Politics of Industrial Accidents,” chap. 3 in The Eclipse of the Utopias of Labor (Fordham University Press, 2018); Karin Bijsterveld, “Listening to Machines: Industrial Noise, Hearing Loss and the Cultural Memory of Sound,” The Sound Studies Reader, ed. Jonathan Sterne (Routledge, 2012); Michael K. Rosenow, Death and Dying in the Working Class, 1865–1920 (University of Illinois Press, 2015).

Mara Mills, “Deafening: Noise and the Engineering of Communication in the Telephone System,” Grey Room, no. 43 (Spring 2011).

Frank B. Gilbreth and L. M. Gilbreth, “Motion Study as an Industrial Opportunity,” Applied Motion Study: A Collection of Papers on the Efficient Method to Industrial Preparedness (Macmillan, 1919), 41.

For more on their use of film, see Scott Curtis, “Images of Efficiency: The Films of Frank B. Gilbreth,” in Films that Work: Industrial Film and the Productivity of Media, ed. Patrick Vonderau and Vinzenz Hediger (Amsterdam University Press, 2009).

More specifically, they insist that the crux of the problem is those “crippled soldiers whose bent is towards some type of physical work,” “whose capabilities and inclinations are confined to physical work.” Gilbreth and Gilbreth, “The Crippled Soldier,” in Applied Motion Study, 134.

As with so much of their work, two tendencies run side by side, and occasionally are inseparable. On one side, there is the absolute centrality of productivity, efficiency, and the measurement of human worth under those terms alone. On the other, there’s a genuine commitment to trying to lessen fatigue, strain, and injury amongst those working, and, especially by Lillian in the wake of Frank’s death in 1924, to build spaces for domestic labor that could be not only efficient but also accessible. For instance, in 1948, Lillian Gilbreth was invited to design a kitchen for Howard Rusk’s Institute of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. In Bess Williamson’s excellent reading of Lillian’s history in this regard, she writes that, “rather than ‘elaborate prosthetic devices’ to adapt the worker to the environment, she wrote, buildings and equipment could be made accessible with ‘simple, inexpensive changes’ that would ‘work wonders.’ Gilbreth’s comments suggest the possibility of more widespread design change, but, like Rusk, she presented the task of producing this design change as a private and domestic one—something housewives could ask their husbands for help installing.” Bess Williamson, Accessible America: A History of Disability and Design (NYU Press, 2019), 54.

Versions of the phrase occur several times in their writing, and with a certain kind of general flattening that organizers like the Wobblies picked up on, albeit for revolutionary reasons. The Gilbreths write that “this country has been so rich in human and material resources, that it is only recently that the importance of waste elimination has come to be realised.” “Motion Study,” 41.

Gilbreth and Gilbreth, “Units, Methods, and Devices of Measurement Under Scientific Management,” in Applied Motion Study, 40.

“Grasp” and “Hold” use an inverted “U” to mimic either fingers or arms that, in “Hold,” now bear a straight line. The lower line of the “Search” eye becomes a bowl or vessel in “Transport Loaded,” then flipped over to “Release Load” and turned right side up again to show “Transport Empty,” waiting for its next cargo.

From Ralph M. Barnes, Work Methods Manual (John Wiley & Sons), 1944; quoted in Elliott Sturtevant, “‘Degrees of Freedom’: On Frank and Lilian Gilbreth’s Allocation of Movement,” Thresholds, no. 42 (2014): 161.

This table, credited to Lillian Gilbreth, is reproduced in Sturtevant, “‘Degrees,’” 165.

Even aside from the especially potent kind of neutralization that management strategies offer, sabotage is up against a broader mesh of ideologies and laws that resists this, politically and technically, putting the locus on the individual citizen and their mediated representation as the correct unit for political engagement.