1. Fabric/Earth

The first image accompanying this text comes from a trial that took place in Guatemala in 2016: the first time in the country’s history that a case of sexual enslavement was considered a crime against humanity under international law.1 The plaintiffs were fifteen Q’eqchi’ women who were forced into servitude and sexual slavery between 1982 and 1983 by a military government detachment after their husbands were murdered and accused of hiding communist leaders. The case became known as “Sepur Zarco,” after the name of the region, and demonstrated the continuity of policies of Indigenous extermination that had been underway since colonial invasion. To protect their safety during the trial, the women covered their faces with shawls known as perrajes, typically used as protection from the cold or for carrying food, objects, or babies.

This text surveys several contemporary artworks that concern Indigenous forms of political identity and spiritual resistance connected to ancestral textile knowledges and their problematic patrimonialization by contemporary nation-states. I weave ecology into this discourse to underline the intimate link between forms of ecological and colonial exploitation. In the case of Sepur Zarco, this link is clear: the Q’eqchi’ community was subjected to cruel torture to interrupt an ongoing attempt at land reclamation grounded in their stewarding of the land since at least the nineteenth century.2 The region has a long history of territorial conflict and labor exploitation by finqueros (agricultural landowners), who frequently called on the army to prevent uprisings. In short, the violence these women were subjected to was part of a system for perpetuating colonial power relations and ecological violence. Survivors’ demands for reparations included developing infrastructure for Sepur Zarco and other nearby areas, health care, the creation of schools, and agrarian reform linked to the return of land to impacted Indigenous communities. Only some of these demands have been implemented thus far, and only in precarious or non-permanent forms, including the return of arable land. Nonetheless, the demands have helped to clarify the current land ownership situation and have put an end to attempts to extort the Indigenous community members.3

In the work of Martinican philosopher Malcom Ferdinand, land theft and ecological exploitation are two sides of the colonial form of governance. Ferdinand argues that there is a fracture in discourses on modernity—one that separates environmental history and ecological problems from colonial history:

The double fracture of modernity refers to the thick wall between the two environmental and colonial fractures, to the real difficulty that exists in thinking them together and that in response carries out a double critique … One either questions the environmental fracture on the condition that the silence of modernity’s colonial fracture, its misogynist slavery, and its racisms are maintained, or one deconstructs the colonial fracture on the condition that its ecological issues are abandoned. Yet, by leaving aside the colonial question, ecologists and green activists overlook the fact that both historical colonization and contemporary structural racism are at the center of destructive ways of inhabiting the Earth.4

Ferdinand draws parallels between the processes of enslavement and the history of land exploitation up to the present day. In a similar vein, in his book The Fourth Invasion, the Guatemalan anthropologist Giovanni Batz traces different environmental invasions from the beginnings of colonization to the present day to reveal the ideological genealogy behind the Palo Viejo hydroelectric plant in the Cotzal region of Guatemala. In this area, the colonial exploitation of land went through several phases, beginning in the late nineteenth century with the development of coffee monoculture and leading to the present-day conflicts.5 A key tactic for expropriating land, argues Batz, was deceiving Indigenous workers and driving them into debt. During the second invasion of Batz’s genealogy, the military became one of the first landowners in certain regions, with the aim of intimidating Indigenous communities into giving up their land so that a national farm economy could be established. Like the Cotzal region, the military occupation of Sepur Zarco in the 1980s was a continuation of the colonial project.

Following the signing of peace accords in 1996 to end the country’s decades-long civil war, Guatemala’s farm economy turned to palm plantations, which have increased 600 percent in recent years, making the country one of the world’s leading cultivators of the crop. Today, Sepur Zarco is beset by these plantations, which render the land infertile over a twenty-five-year period, destroy local biodiversity, and pollute the water and air.6 As Ferdinand remarks:

In addition to the genocide of indigenous peoples and the destruction of ecosystems, this colonial inhabitation transformed the land into the jigsaws of factories and plantations that characterize this geological era, the Plantationocene, resulting in the loss of caring and matricial bonds with the Earth: matricides.7

2. What Do We Owe the Grandmothers?

The phrase “De ellas no se sabe nada” (nothing is known about them) has been written on a thread winder in Ángel Poyón’s artwork Devanador del silencio (Silence Winder, 2013). The phrase turns on an axis that passes repeatedly through a weaver’s gaze. It is no coincidence that in the Spanish phrase, “ellas” is in the feminine. If this circular movement is the basis of the action of weaving, the repetitive phrase engraved on the winder ends up becoming a mantra: the response given by mothers and grandmothers every time they are asked about their disappeared loved ones. The Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH, created by the Guatemalan government and the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity political party) estimates that during the thirty-six years of civil war in Guatemala, and especially in the 1980s, when a Mayan genocide took place in which the Q’eqchi’ people were the most affected, there were two hundred thousand deaths, five thousand people disappeared, and 626 massacres of Mayan people, 93 percent of whom were killed by military forces. The title of Poyón’s work is meant to ask how to performativize mourning in everyday life, how to learn to assimilate the lack and violence of silence about the disappearances. The great emptiness of “the disappeared” interrupts the oblivion of the war and points to impunity. Through this (state-sanctioned) silence, the disappeared disappear again.

Angel Poyon, Devanador del silencio (Silence Winder), 2013.

This is also illustrated by the image of the Sepur Zarco trial that leads this text, in which the plaintiffs’ faces disappear as a form of protection. Accused of collaborating with the military, these women lived in internal social exile—and endured economic precarity as a result—until they prevailed at trial in 2016.8 The gesture of hiding shows the latency of fear, whose intimate counterpart is shame: two emotions linked to trauma and the loss of control that feed off each other.9 Shame involves the negating personhood, or depersonification.10 Studies on shame show that it has a contagious nature. And in cases of oppression, shame is shared by both victims and oppressors.11 Only after the conviction of the defendants from the military did the women uncover their faces and become community leaders and “Grandmothers,” a crucial role given to people in this community who are important to collective identity.12 Thanks to the Grandmothers of Sepur Zarco, a silence was broken, after which many other women dared to speak out and began to tell their stories and take other officials to court. Protocols began to be created (by Equipo de Estudios Comunitarios y Acción Psicosocial, ECAP) to provide psychological help to survivors of wartime rape.13 Often the Grandmothers have attended the resulting trials and have counselled the plaintiffs.

Also in 2016, artist Regina Galindo created a private performance titled Ascension in the San Matteo Church in Lucca, Italy, where she covered herself with ten meters of perraje woven by a Mayan weaver. Taking on the appearance of the Virgin, the artist spoke of the sacred status of Grandmothers, in an act of monumentalization and sanctification. Appearing wrapped in the perraje was an allusion to the holiness of wrapping in some Mayan cultures, where valuable objects are wrapped and charged with ancestral energy and a sense of the sacred: objects from ancestors and those with a connection to the divine that concentrate energy, such as stones.14 Likewise, the sacred book Popol Vuh, published in the early eighteenth century, relates the origin of the world from the Maya K’iche perspective. It speaks of the origin of humanity through the first corn men who left wrappings, known as sacred bundles, as objects of worship and remembrance. Here the textile functions as an element of the relationship between the ancestral-spiritual and the human, dispelling the difference between the living and the dead and creating new relationships between them.15 This sacredness also implies protection and intimacy; the spiritual charge of the wrappings cannot be separated from their opacity and protection. In this way, as Galindo’s work puts forward, the gesture of concealing oneself behind the perraje ceases to allude to a social stigma, to fear or shame, and transforms instead into an act of sacredness.

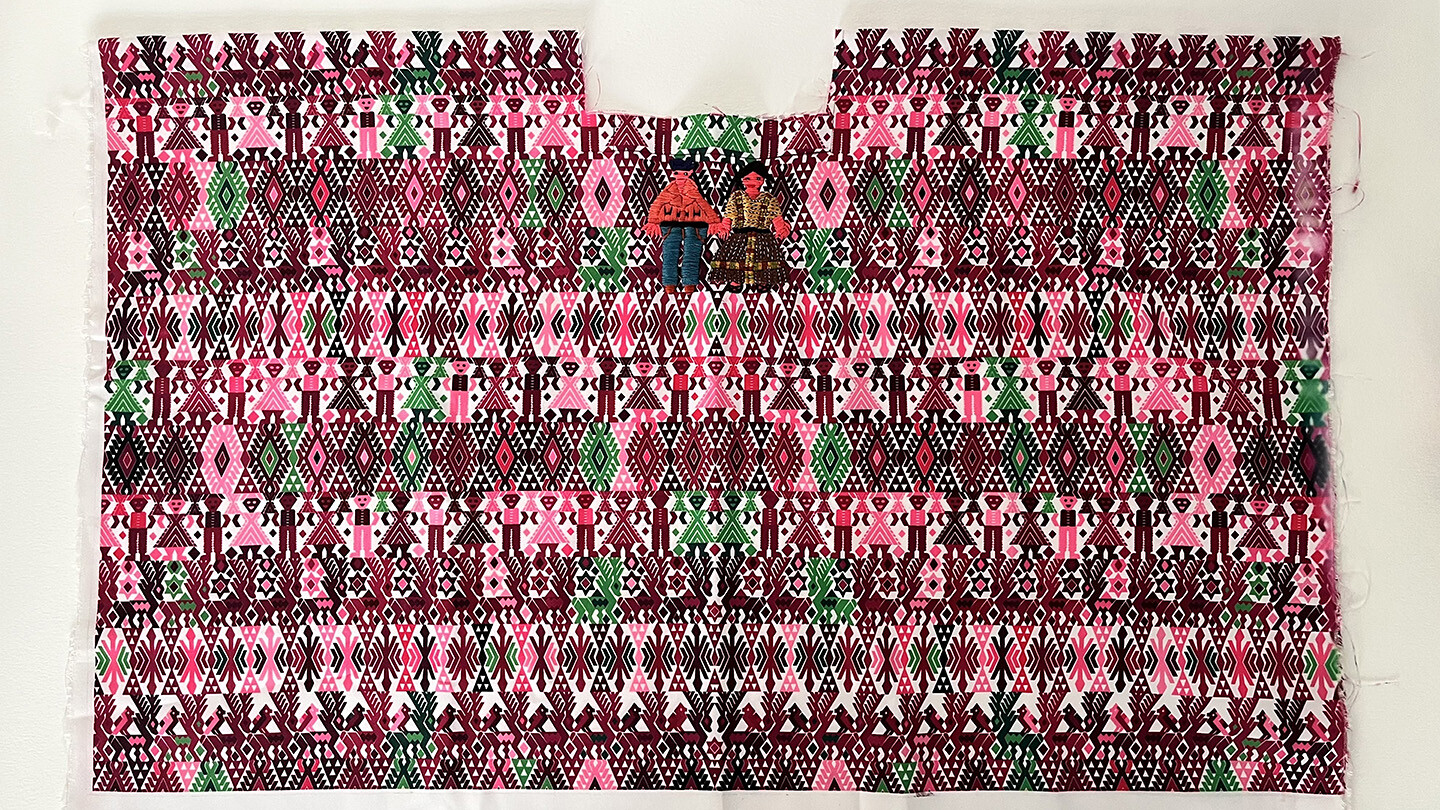

Textiles express ancestral knowledge of geometry and mathematics connected to the Mayan worldview, incorporating elements of politics, nature, history, and memory. Each community has different colors, embroideries, and figures that have been passed down from generation to generation. As the slogan of the National Movement of Women Weavers says: “The weavings are the books that colonialism could not burn.”16 This umbrella group was created in 2014 and is made up of thirty associations of women weavers. It was formed to defend the rights of women producers against companies that were beginning to commercialize their products and exploit their ancestral knowledge. Exploring the link between textiles and the ecological question, the Kaqchikel artist Marilyn Boror, in her work Rewrite, Re-read (2018), asked twelve Kaqchikel women weavers from different communities to express through their embroidery their resistance against the San Gabriel Cement Company (San Juan Sacatepéquez), which privatized land containing ancestral roads that connected communities. The women’s embroidery was done on Güipiles (blouses) made serially in a factory—a type of garment that is increasingly replacing the original handmade ones, endangering the entire system of knowledge that the weavers carry. Therefore, it makes sense to restore manual work by rewriting on these manufactured and machine-made garments: to embroider on them is to give back to the Güipil the hand of the weaver, and with it the history, the language, the knowledge, the emotions, and the struggles that are absent in the clothes made in series by machines. In this way Boror puts on the same level the resistance to land expropriation and the struggle to maintain textile knowledge. As the Kaqchikel anthropologist Irma Otzoy has pointed out:

Both land and weavings form the core foundations of [Mayan] existence. Perhaps unsurprisingly, because of land and weaving, the Maya have been, albeit in different ways, unfavorably targeted for reprisals. Historically, the Maya have fought and resisted especially for the protection of their land and weavings, and have always been determined to maintain them.17

Marilyn Boror, Rewrite, Re-read, 2018.

Marilyn Boror, Rewrite, Re-read, 2018.

Marilyn Boror, Rewrite, Re-read, 2018.

Marilyn Boror, Rewrite, Re-read, 2018.

In her book La Guerra Contra las Mujeres (The war against women), Rita Segato documents a radical change in the way women’s bodies have been targeted in relation to the occupation of territory. From the beginning of European invasion through to the twentieth century, argues Segato, women’s bodies were “appropriated, raped and inseminated as part of the territories.” Today, colonial femicide takes on a different meaning:

It is the destruction of the enemy in the body of the woman. The female or feminized body is … the very battlefield on which the insignia of victory is signified, where the physical and moral devastation of the people, tribe, community, neighborhood, locality, family, or gang that this female body, through a process of signification typical of an ancestral imaginary, embodies, is inscribed. It is no longer its appropriating conquest but its physical and moral destruction that is executed today, a destruction that is extended to its tutelary figures and that seems to me to maintain semantic affinities and also to express a new predatory relationship with nature, until only remains are left.18

As a tool of warfare, feminicide denigrates community members, undoes family ties, and attacks the identity of the collective.19 For these reasons, in their expert testimony during the Sepur Zarco trial, both Irma A. Velásquez Nimatuj and Rita Segato insisted that this aggression was not intimate or based on personal hatred but was a destructive political strategy.

The word “rape” does not exist in the Q’eqchi’ language. Instead, the Grandmothers spoke of “profanation.” Women who perform reproductive labor in their communities were “profaned” when their families were destroyed and their reproductive organs damaged, dismantling a social and spiritual world. In this way, the concepts of trauma and reparation should be considered from an epistemological level. For example, the Kumool Association of Ixil and K’iche women ex-combatants chose the concept Txitzi’n to express trauma.20 In Ixil, this concept means “deep pain” and “wounded soul,” in which a part of the subject is dead. But as a mystical inner experience, it expresses a space of knowledge production that encompasses both trauma and healing and therefore it “is not imbued with the idea of helplessness.”21 In the case of the Grandmothers of Sepur Zarco, it is important to note that reparation did not involve an individual process of healing, as it would in the West. Rather, as mentioned above, the demands of the victims were centered on the collective and were framed as “transformative reparations measures.”22 This concept became an important precedent for other lawsuits. This is an example of what has been called the “feminization of struggles” in Latin America.23

3. Heritagization: What Is Owed to the Weavers?

Sandra Monterroso’s work Columna vertebral (Backbone, 2012) is a totem monument made from eighty-seven skirts of Q’eqchi’ women from her family. These skirts are traditionally made by men with a foot-operated loom. Called “corte textile,” the skirts in Columna vertebral are rolled up—the way they are kept in Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Monterroso’s grandmothers and aunts made a living sewing when they migrated to the city, which inspired her to have conversations with them and document these conversations in a diary. In this way, each “corte” generated an encounter. The diary writing is part of Columna vertebral and functions as a space for reflection on Q’eqchi’ culture and the artist’s own links with the women in her family.24 The “backbone” in the title of the work recognizes the place of these women and textiles at the center of the community, as preservers of its history and culture. Indigenous feminism (although it cannot be fully understood in Western terms) has looked at how this role tends to objectify these women and make them passive—prompting Kaqchikel anthropologist Aura Cumes to ask how this preserver role can be rethought to make these women into political subjects. One of the aims is therefore to question the passivity of this role and re-signify it into a role with political agency.

While contemporary Guatemalan society urges Indigenous women to shed their traditional dress—for example, by not allowing women in traditional dress to enter restaurants, or by treating them as servants in the street—tourism agencies have instead demanded that these women not mix their regional costumes with modern garments so as not to confuse tourists. The National Tourism Institute has even asked women weavers to be more flexible about the prices of their products so that tourists can have a satisfactory “haggling” experience. As Cumes shows, in this commercialization of textiles there is a contrast between the high market value assigned to the garments and the common disregard for their creators.25 In this way, both the costume and the woman who wears it are objectified and discarded.26 It is symptomatic that the first Indigenous textile shop in Guatemala City was set up in the nineteenth century by the American Tocsika Roach. It is even more symptomatic that she sold her collection to the US-based United Fruit Company, which has a long and well-known history of exploitation in Guatemala and elsewhere. The United Fruit Company has since donated its collection to the National Museum of Guatemala City.

The Ixchel Museum of Costume in Guatemala City, founded in 1973, preserves textile techniques and pieces. It has a room dedicated to the perraje. Named “Sala Carolina Mini Su’t: Uses and Meanings,” the room has a wall label that reads: “Su’t is a word used in several Mayan languages and in Spanish. It designates a cloth, handkerchief, or napkin … [A su’t] has many uses. You can fold it in a certain way for it to function as a jumper or bag, among other things.” Given the political charge of Mayan dress, such a space could help recognize the political agency of women and the complexity of the symbolic value of self-determination that dressing implies. Instead of being an agent of conservation through the rhetoric of artistic patrimonialization, such a museum could re-signify Indigenous female bodies and promote the public recognition of their collective mourning, inviting the spectator to evaluate their own position in this social body.27

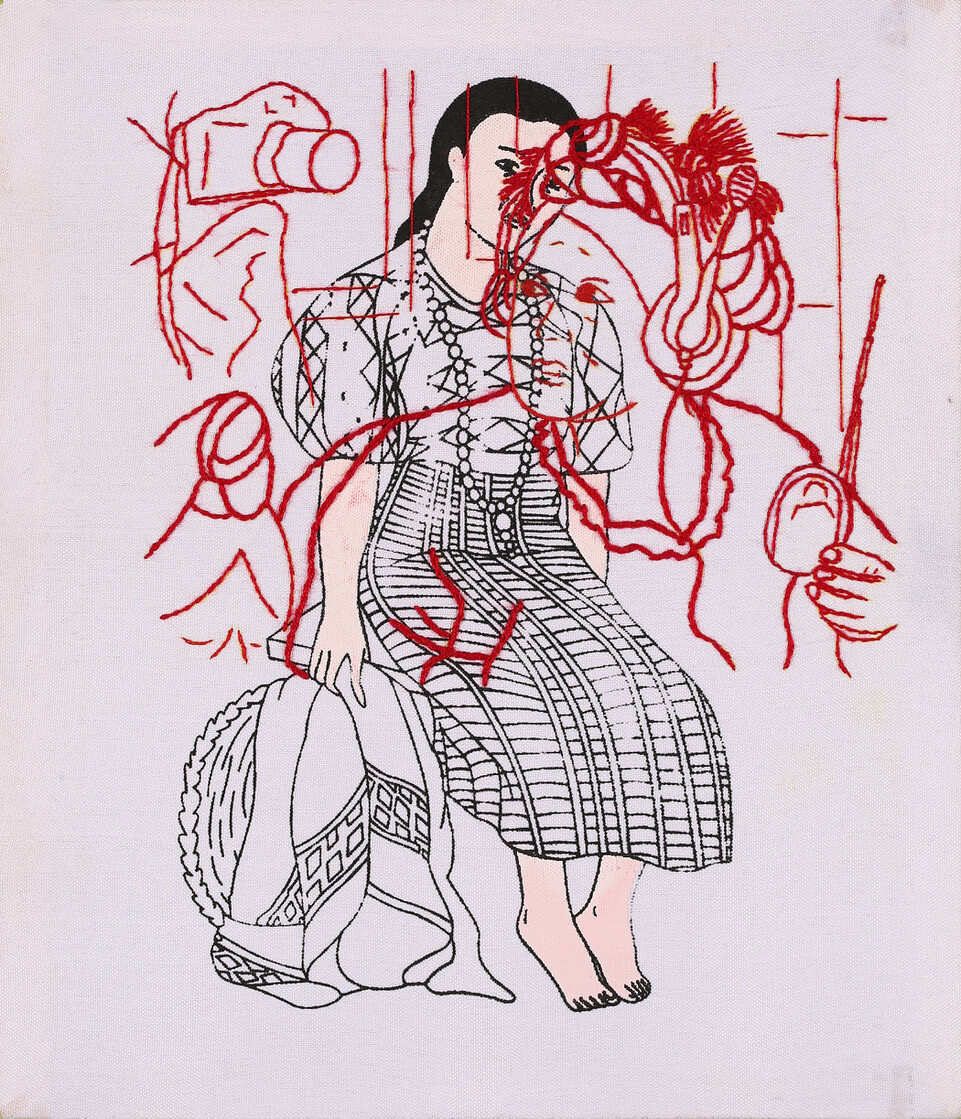

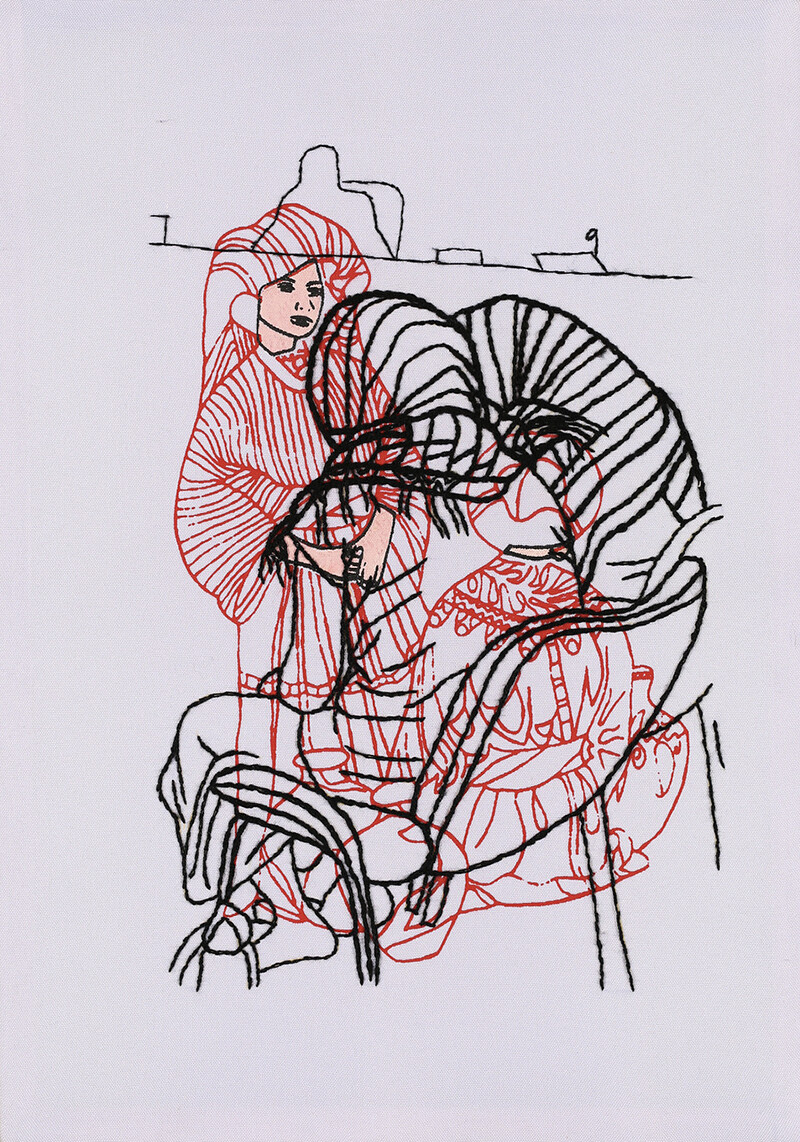

Andrea Monroy, Sepur Zarco Case, 2016.

Andrea Monroy, Sepur Zarco Case, 2016.

Andrea Monroy, Sepur Zarco Case, 2016.

Andrea Monroy, Sepur Zarco Case, 2016.

Contemporary art often points to other tasks museums should perform instead. The same year as the Sepur Zarco trial, artist Andrea Monroy stitched embroideries while listening to the testimonies of the Indigenous women in the trial. She superimposed images of the Grandmothers speaking at the trial on embroidery stencils that featured so-called “typical pictures” of Indigenous women. These bucolic, touristy images of Indigenous women represent them performing domestic chores—passive, silent, submissive. The images of the Grandmothers that Monroy reproduced on the picturesque stencils show their gesture of hiding behind the perraje as they testified at the trial. That is, the work makes the mourning and suffering of the Grandmothers visible while also showing their agency as plaintiffs in the lawsuit. It invokes the hidden face of the national discourse of folkloric whitening, where Indigenous people are reduced to passive emblems of the past.28 It performativizes the repetitive, slow, and delicate activity of embroidering, in an act of accompaniment and listening to the Grandmothers. It creates space and time for accompanying, mourning, and performing pain, but it also supports the Grandmothers’ insubordination toward these folkloric images that suffocate their true reality.

The national patrimonialization of Mayan culture has generally been understood by Indigenous communities as a tool of control and dispossession. An epic Mayan past is folklorized to become part of the national imaginary, while the public voice of its cultural producers is denied.29 This privatization of culture, whether it takes places in the realm of museums, tourism, or the commercial appropriation of textiles, uses nationalist rhetoric that reproduces colonial grammar. In 2017, the National Movement of Women Weavers presented a bill to the Constitutional Court of Guatemala. This bill aimed to recognize the collective intellectual rights of Indigenous cultural producers and to protect Indigenous textiles from appropriation by large high-fashion brands. The ensuring debate showed how ownership is not compatible with a society that is not based on a formal legal code, a society of ancestry and cultural communities. There was a failure to understand collective and ancestral property precisely because it is not compatible with the neoliberal system of property. In 2019 the National Movement of Women Weavers demanded that the National Tourism Institute of Guatemala stop reproducing Indigenous images and commodifying Indigenous ways of life without consulting Indigenous people. The group issued this demand not only because these images often reproduce racist stereotypes and use oversimplified concepts such as “handicrafts,” but also—and above all—to reclaim their sovereignty over their own cultural production.30

4. The Perraje, the Lake, and Food Sovereignty

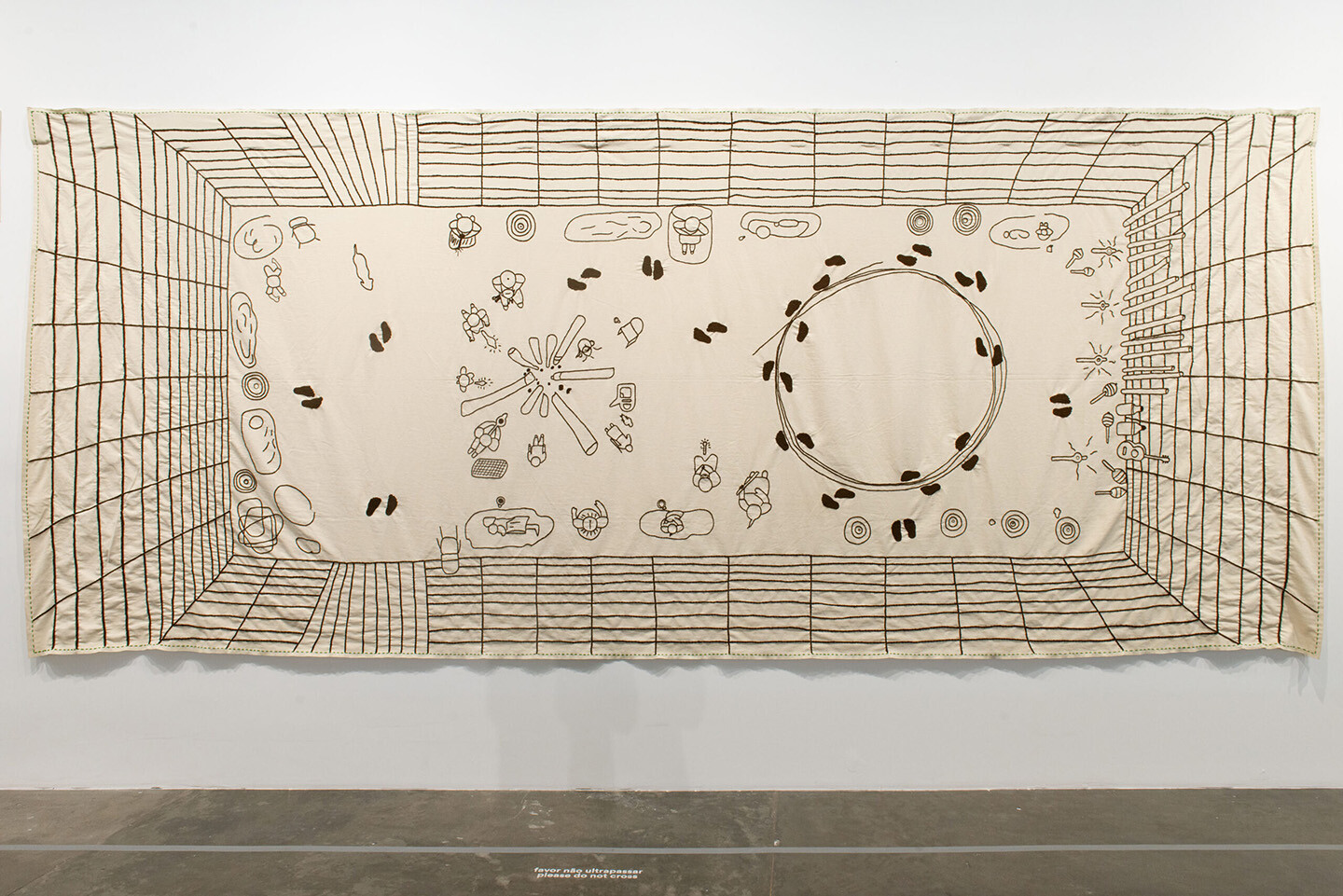

The Kaqchikel artist Edgar Calel stayed in the Guarani village of Kalipety (province of São Paulo) to create a work for the 35th São Paulo Biennial entitled Nimajay Guarani (Big Guarani House, 2023). This village was founded in 2013 by Jerá Guarani, who broke with patriarchal and vertical leadership dynamics to create her own community project for “food sovereignty.” The project focused on the cultivation of peanuts, manioc, jety (Guarani sweet potato), and corn. From different parts of Argentina and Brazil she gathered, cultivated, and mixed fifteen different species of maize, creating an important seed bank. She also rescued and published traditional recipes. For the Guarani people, the recovery of maize has an important spiritual dimension insofar as it strengthens their connection to their ancestors and protects their descendants.31 Inspired by this project, Edgar Calel presented a mural made of fabric with forty-eight embroideries of various species of maize and manioc. These embroideries were arranged around a central representation of the daily life of the inhabitants of Kalipety village, featuring musical instruments, chairs, and a large fire. The Mayans also consider maize, which has been cultivated for more than ten thousand years in Central America, a sacred plant. According to the sacred book Popol Vuh, it is the material from which man is made. If the planting of this maize-subject organizes daily life, Calel shows a domestic ecosystem and renders homage to female leadership, while aligning textile production with ecological sustainability and the recovery of the land. Inspired by the Jerá Guarani project, other women-led villages were founded in the region in the following years.32

Exhibition view of Edgar Calel’s Nimajay Guarani during the 35th Bienal de São Paulo, “Choreographies of the Impossible.” Image courtesy of the artist and Proyectos Ultravioleta. Photo by © Levi Fanan.

Exhibition view of Edgar Calel’s Nimajay Guarani during the 35th Bienal de São Paulo, “Choreographies of the Impossible.” Image courtesy of the artist and Proyectos Ultravioleta. Photo by © Levi Fanan.

Exhibition view of Edgar Calel’s Nimajay Guarani during the 35th Bienal de São Paulo, “Choreographies of the Impossible.” Image courtesy of the artist and Proyectos Ultravioleta. Photo by © Levi Fanan.

Indigenous epistemologies have a way of looking at the earth that is not marked by the modern ecological fracture. Considering this alongside Ferdinand’s proposal for a decolonial ecology, it becomes possible to “forge interspecies alliances where the cause of animals and the demand for the emancipation of Negroes are seen as common problems” in order to enact a “change of scene from which discourses and knowledge are produced.”33 Ferdinand follows in the wake of concepts developed by other Martinican writers, such as the “creolization of the world” proposed by Édouard Glissant; but Ferdinand goes a step further by including nonhuman agents in the relational equation.34 Thus Ferdinand’s concept of an ecology-of-the-world has as its horizon the creation of epistemically diverse political forms:

Starting from the constitutive plurality of human and nonhumans on Earth, of different cultures, taking the world as the object of ecology brings back to the fore the question of the political composition between these pluralities, and therefore the question of acting together as well.35

This is also the basis of Marisol de la Cadena’s proposal in her paradigmatic 2009 text “Política Indígena: Un Análisis Más Allá de ‘la Política,’” (Indigenous politics: An analysis beyond “politics”).36 Here she describes how nature has been exiled from politics since Hobbes in the seventeenth century, when its relationship to the nonhuman and the spiritual was denied. The sciences gained a monopoly over the representation of nature and by extension of Indigenous peoples, who were regarded as living in a natural state. They were thus exiled from the political, which can still be seen today. Here is what the Tz’utujil artist Nuto Chavajay wrote in a 2020 text coauthored with me: “Intellectuals and pseudo-leftists secularized our symbols, erased our signs, disembodied our wisdom in the spelling of the word, for fear that the stones would speak.”37 De la Cadena insists that in order to create spaces of “the political” that do not exclude other epistemologies, there must be an ontological-political decentering of modern politics. Recognizing the crucial place of nature in politics also includes recognizing the political sphere of indigeneity. It will not just be a matter of pluralizing voices or including them within the same framework, but of pluralizing politics itself.

Manuel Chavajay, Ru jawal ya’, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

Working from this union between ecology and textiles, in the same year as the Sepur Zarco trial and as a tribute to the Grandmothers’ leadership Manuel Chavajay initiated a series of works entitled Ru jawal ya’ using a perraje with the colors of maize. The work shows an image of a lake that the artist derived from the dreams of the grandfathers and grandmothers he consulted. In these dreams the lake is a woman whose hair blends with her perraje.38 Chavajay’s use of the perraje evokes the “matricial” vision of the earth that Ferdinand spoke of, and recognizes this vision as a living entity to be respected and cared for by the whole community. The presence of an oar in the work pays homage to a relational tool with the lake, as an extension of the body.

In her recent book Entre la Exotización y el Mayámetro: Dinámicas Contemporáneas del Colonialism (Between exoticization and mayameter: Contemporary dynamics of colonialism), Maria Jacinta Xón tracks how US academics created concepts around “being Mayan” that later, in the 1980s and ’90s, were absorbed by Mayans who led movements for the institutionalization of identity. These Indigenous intellectuals had been educated in religious boarding schools and got their political training in NGOs. Xón reveals that during the 1996 peace negotiations at the end of the Guatemalan civil war, there was only one Indigenous person present and involved in writing the peace agreement. This person’s work had to be based on documents created by Indigenous people trained outside the country by foreign, mainly North American academics (“linguistic, anthropological, archaeological and ethnological studies”).39 These homogenizing identity categories and politics were often divorced from everyday practices, stifling popular conceptions of those practices. This is a case of nawalismo which, as Xón shows, is a Western concept that has as many as five potential translations in Mayan languages. There is no direct translation from Spanish. The category nawal was created by foreign indigenist scholars and “mediated by so-called Mayan intellectuals and NGO leaders as structuring elements of the Indigenous knowledge system.”40 This is the process of the neo-hegemonization of what has been called “Mayanization,”41 a discourse of authenticity that has usurped “the everyday life of those who perform their services helping their peers and collectives.”42

Manuel Chavajay is involved in the recovery of the nawal system of thought from the experience of his ancestors. The artist thinks of the nawal of the lake as a female presence wrapped in a textile, protected but at the same time enveloping and protecting with her perraje. The textile and the earth are aligned in this work on the lake through all the meanings it unfolds. Like much of the art in this text, Chavajay’s piece is part of a collective mourning that runs through the lives of this postwar generation of artists. This is especially evident in the pieces by Ángel Poyón, Regina José Galindo, and Andrea Monroy, who confront colonial trauma in order to performativize it from a feminine perspective and to traverse it in the present. All these artists put on the same level the defense of cultural production and the defense of the land, united to overcome the double colonial fracture described by Malcom Ferdinand. This feminization of political struggles, also evident in the work of Edgar Calel, Sandra Monterroso, and Marilyn Boror through textiles, is inseparable from struggles for the environment and the defense of all life-forms.

Marilyn Boror, Monumento Vivo (Living Monument), performance, 2021.

We could easily include the Indigenous women of Sepur Zarco within this larger ecofeminist movement, since they represent a culture of care that challenges the neoliberal extractivist viewpoint through the defense of collective life and the de-hierarchization of the nonhuman.43 This was expressed clearly by one of the Sepur Zarco Grandmothers, Demecia Yat, when she declared that they demanded land so that their grandchildren do not depend on money and the purchase and consumption of food. The horizon of the reparation demanded by the Grandmothers is a community that can subsist by growing beans, cassava, and chili, as they did before the armed conflict. But this also has to do with domestic and care work understood in its most profoundly political dimension, beyond the contempt that Western feminism has shown it in the name of liberation. That’s why there has been much debate in Latin American over whether this movement should be assimilated by middle-class Western feminism, and whether it should even be called feminist at all, since the “feminization of struggles” is above all a struggle for survival, for the defense of territory, and for ways of life.44 Xón explains:

The body of knowledge and know-how that Indigenous women have created is unquestionable—knowledge they have dynamized inter-generationally despite the logics of oppression/resistance and the multiple forms of violence in which they have lived. What would Mesoamerican life be without the nixtamalization of maize, nutritional supplements in agricultural production and cooking, the safeguarding and exchange of seeds, among the knowledge of Indigenous women in the world? This is why today it is essential to make agricultural and domestic spaces into political spaces.45

It is therefore no coincidence that Marilyn Boror, in her performance Monumento Vivo (Living Monument) (2021), presented herself in the Central Plaza of Guatemala City dressed in the Mayan costume of her village, San Juan Sacatepéquez, on a cement base with her feet trapped by the cement. In this act of physical resistance to the pressure of the cement in its process of solidification, she critiques the cement company San Gabriel and its actions in her region. She denounces the presence of cement as a symbol of progress that is devastating her people’s way of life and relationship with nature. Above all Boror addresses the crucial place of women, not as passive monuments preserving a cultural/identitarian tradition and the environment, but above all as living political agents engaged in a resistance they have been forced to lead. A plaque on this “living monument” reads: “In memory of the defenders of the earth, in memory of the spiritual guides, in gratitude for the political prisoners, in gratitude for the community leaders, in gratitude for the rivers, the hills, the mountains, the flowers, the lakes!”

See the testimony of Paloma Soria Montañez in Susana Sá Couto, Alysson Ford Ouoba, and Claudia Martin, Documenting Good Practice on Accountability for Conflict-Related Sexual Violence: The Sepur Zarco Case (UN Women, 2022), 74 →.

See statements by anthropologist Laura Hurtado in the documentary on Sepur Zarco Mi Corazón está Conento →.

Couto, Ouoba, and Martin, Documenting Good Practice, 98.

Malcom Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World (John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 2021), 8, 11, emphasis in original.

Giovanni Batz, La Cuarta Invasión: Historias y Resistencia del Pueblo Ixil, y su Lucha Contra la Hidroeléctrica Palo Viejo en Cotzal (Avancso, 2022), 49. Unless otherwise specified, all translations are by the author. In the early twentieth century the United Fruit Company begin to establish itself in the country, acquiring 40 percent of Guatemala’s arable land; see → (in Spanish).

Report by the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona → (in Spanish).

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 21, emphasis in original.

See Irma Alicia Velásquez Nimatuj, La Justicia Nunca Estuvo de Nuestro “Lado”: Peritaje Cultural Sobre Conflicto Armado y Violencia Sexual en el caso Sepur Zarco, Guatemala (Universidad del Pais Vasco 2019); recordings available here →.

Ashwin Budden, “The Role of Shame in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Proposal for a Socio-emotional Model for DSM-V,” Social Science & Medicine Journal, no. 69 (2009).

Donald Nathanson, “Understanding What Is Hidden: Shame in Sexual Abuse,” Psychiatric Clinics of North America 12, no. 2 (June 1989).

Couto, Ouoba, and Martin, Documenting Good Practice.

Daniel Grecco Pacheco, “Ontologías Envueltas: Conceptos y Prácticas Sobre los Envoltorios de Tejido Entre los Mayas,” Antípoda: Revista De Antropología Y Arqueología, no. 37, (2019).

ECAP “is an organisation dedicated to helping individuals and communities recover from the psychological, social and cultural damage caused by political violence in Guatemala.” Couto, Ouoba, and Martin, Documenting Good Practice.

Pacheco, “Ontologías Envueltas,” 129.

María Iñigo Clavo, “Traces, Signs, and Symptoms of the Untranslatable,” e-flux journal, no. 108 (April 2020) →. See also Pacheco, “Ontologías Envueltas,” 129.

Aura Cumes, “Peritaje Cultural y Género: Saberes Colectivos de Mujeres Mayas Frente a la Lógica Mercantilista del Tejido Maya,” 2016, unpublished text.

Irma Otzoy, “Identidad y Trajes Mayas,” Revista Mesoamérica, no. 23 (June 1992).

Rita Segato, La guerra contra las mujeres: Traficantes de Sueños (Madrid, 2016), 185–86.

See Irma A. Velásquez Nimatuj’s 2020 public talk “Justice Beyond the Final Verdict: The Sepur Zarco Case” →.

Rosalinda Hernández Alarcón et al., Memorias Rebeldes Contra el Olvido (Cuerda, 2008).

Arturo Arias, “Letter from Guatemala: Indigenous Women on Civil War,” PMLA 124, no. 5 (October 2009): 1895.

Couto, Ouoba, and Martin, Documenting Good Practice, 85.

Maristella Svampa, “Feminismos del Sur y Ecofeminismo,” Nueva Sociedad, no. 256 (March–April 2015).

See Sandra Monterroso’s blog → (in Spanish).

Cumes, “Peritaje Cultural y Género,” 2016.

Irma Alicia Velásquez, “Traje, Folclorización y Racismo en la Guatemala Posconflcito,” in Racismo en Guatemala: De lo Políticamente Correcto a la Lucha Antirracista—Guatemala, ed. Meicke Heckt and Gustavo Palma (Instituto AVANCSO, 2004).

Cristina Lleras et al., “Curatorship for Meaning Making: Contributions Towards Symbolic Reparation at the Museum of Memory of Colombia,” Museum Management and Curatorship 34, no. 6 (November 2019).

See Sandra Xinico’s interventions in De lo Propio a lo Común, a publication that brings together reflections from the conference “Hacia un Replanteamiento de los Derechos de Autor: Colectividades, Redes de Colaboración y Acceso Abierto,” El Centro Cultural de España en Guatemala, 2019.

Cumes, “Peritaje Cultural y Género,” 2016. See also Ana María Alonso, “Políticas de Espacio, Tiempo y Sustancia: Formación del Estado, Nacionalismo y Etnicidad,” in Las Ideas Detrás de la Etnicidad: Una Selección de Textos para el Debate (Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesomérica, 2006).

See De lo Propio a lo Común.

I am very grateful for my collaboration with Maria Thereza Alves, which has allowed me to talk with Jerá Guarani and to learn more about her project.

Aves Isabela, “Aldeia Liderada por Jera Guarani Completa 10 Anos e se Torna Exemplo de Sustentabilidade,” Mural, January 31, 2024 →.

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 44–45, 31.

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 331.

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 40, emphasis in original.

Marisol De la Cadena, “Política Indígena: Un Análisis Más Allá de ‘la Política,’” Red de Antropologías del Mundo, no. 4 (2009): 139–42.

Nuto Chavajay Ixtetelá and María Iñigo Clavo, “Por Miedo a que las Piedras Hablen,” Revista Concreta, no. 16 (Fall 2020), 111. Translated as “‘For a New Gentleness,” CPSA Quarterly, no. 33 (October 2020).

Unpublished text by the artist.

Maria Jacinta Xón, Entre la Exotización y el Mayámetro (Catafixia, 2023), 22.

Xón, Entre la Exotización, 45.

Santiago Bastos and Aura Cumes, Mayanización y vida Cotidiana: La Ideología Multicultural en la Sociedad Guatemalteca (FLACSO sede Guatemala, 2007).

Xón, Entre la Exotización, 43.

Marta Pascual Rodríguez and Herrero López Yayo, “Ecofeminismo: Una Propuesta para Repensar el Presente y Construir el Futuro,” CIP-Ecosocial: Boletín Ecos, no. 10 (2010).

Svampa, “Feminismos del Sur y Ecofeminismo,” 139–42.

Xón, Entre la Exotización, 43.

Subject

This research was originally conducted for the workshop “Gendered Approaches to Restitution: Labor, Migration, Structural Amnesia, and Trauma,” organized by Ariella Azoulay, Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali Zamindar, and Yannis Hamilakis at the Watson Institute, Brown University, USA. I would like to thank Maria Jacinta Xón for her cogent and caring review of this text, which has been nourished by her valuable teachings. I dedicate this text to Ignacio Cardenal, with gratitude for all the hours.