When the US Constitution was drafted, the definition of the word “art” didn’t exactly coincide with today’s Art Basel version. On the positive side, Clause 8 recognized intellectual work as a form of actual labor. The founding fathers would have supported my demand for a dollar. On the negative side, Clause 8 set down guidelines that, by promoting applied knowledge in a world defined by the hope for certainty, have today culminated in the push for STEM curricula. “STEM” stands for “science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.” One could say that, in practical terms, the ideological split between Kant and the US Constitution ended with Kant’s defeat. The Constitution identified knowledge with scientific knowledge, distorted education to function as training for the labor market and national glory, and fragmented knowledge into information units that can be quantified and measured in order to create a meritocracy. Grading and credit systems were predictable and inevitable.

The grading system in the US is based on the British shoe quality-control system. It was translated for academic use in 1792 by William Farish, a teacher at Cambridge. The US credit system appeared a century later in the form of Carnegie units designed to calculate the pensions of retiring teachers. Neither shoe manufacturers nor the pensions’ actuarial accountants were aware of the consequences of their actions. The most basic education relies on being able to write and read an accumulation of letters for literacy, and an accumulation of numbers for numeracy. The pursuit of imagination stops abruptly after kindergarten. From then on, artistic proclivity is identified with good motor skills and knowledge about what has been previously done and historically approved. As an artist, I assert that this is a fraudulent presentation of my profession. It leads to trying to understand an apple tree by analyzing the color and shape of the apples. The tree, however, is a little more complex.

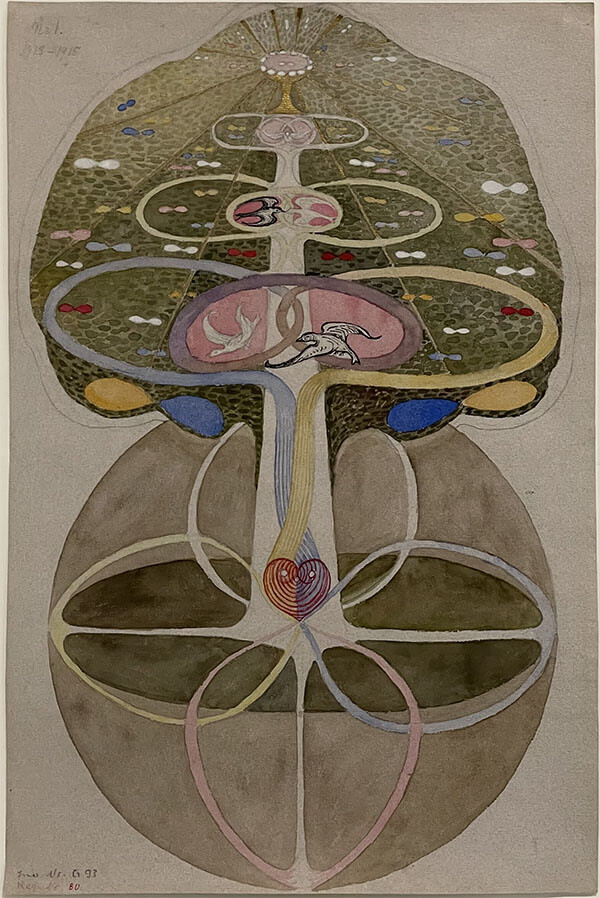

The image of the tree of knowledge is as old as Eve biting into an apple, but here it helps clarify some things about art. At its bottom there is art as a root activity. At this level, the raw creative impulse meets with a desire to impose order upon it, which is a basic human reaction. Then there is the trunk, where that order is codified into what some people call art as a language. Finally, there are the branches—in fact disciplinary or craft branches, from which we see fruit hanging. When ripe and attractive we call these fruits works of art and we want to consume them, or even better, own them. That is where we write “Art” with a capital “A” and believe that this is all art is. We compare the fruits, evaluate them, and give them a price. We forget that the whole thing comes from a process where “art” is written small, where it deals with knowledge, where the creative impulse travels from the roots up and not from the fruit down. The fruit is there only to help us retro-engineer the process, and much of it eventually rots and falls into a heap of compost. I used to have my students study the past twenty-five years of Artforum covers. They were supposed to determine how many, or actually how few, of the artists featured are still consequential today. They were supposed to see how the forgotten artists now serve as fertilizer.

Hilma af Klint, Tree of Knowledge, No. 1, 1913–15. License: Public domain.

The point is that creativity is a generative but normal cognitive activity. When people say that everyone is an artist, this is a confusing statement. I, at least, visualize multitudes of people painting little canvases while having dinner, riding the subway, or walking in a park, without any further social or cultural value. By “normal cognitive activity” I mean that the possibility of creating something that didn’t exist before is not confined to a few traditional media or a few specialized performers seeking recognition. It is a way of reacting to our environment, and developing it should be an intrinsic part of regular education.

This is particularly important because of the increasing dominance of STEM education at the expense of subjects that deal with nonpractical ideas, as is the case with the humanities. There is nothing wrong, of course, with developing science and technology as much as possible to solve human problems and improve society. However, the study of ethics that might ensure the correct use of science belongs to the humanities. Also being pushed out is a respect for inapplicability and uselessness. Even at the preschool level toys are now designed to guide children into becoming computer programmers or entering STEM fields.

Maybe we should ask, then: “What is the purpose of education?” In 2012, José Ignacio Wert, the Spanish minister of education, said that “the arts distract from education.”1 In 2016, US senator Marco Rubio expanded Wert’s theory by noting that welders earn more than philosophers, so therefore we need more welders. These comments focus on personal survival in the labor market. To attract students, STEM disciplines frequently assert that studying them makes you more employable. In this way, jobs have become the main justification for education. When experts discuss the impact of Covid on students, they focus on how the labor market will be adversely affected when these students reach employment age. They don’t focus on how the pandemic stunted the personal maturation of students. The influential Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which measures educational success in countries across the globe, tries to predict this effect while ignoring the consequences of the lack of socialization and nutrition that Covid created in primary school. The reason for this is that PISA is concerned with national standing, not personal development.

This is nothing new. It is part of a dominant way of thinking that, since the US Constitution of 1788, has focused on national competitiveness and supremacy. This way of thinking peaked in response to the Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957. Later, Ronald Reagan pursued it as an answer to the Nation at Risk report. The acronym “STEM” was created in the early 1990s by Charles Vela, a Salvadorian immigrant and scientist. Vela developed a curriculum to improve work opportunities for Latino students, which was then endorsed and taken over by a series of US presidents to maintain international technological leadership. The question here is if STEM, or any training focused on employability, deserves to be called education.

While training focuses on doing jobs well, education is supposed to help students mature. Literacy and numeracy certainly are important for both, so much so that people lacking these skills are considered unfit to function in society. There are, however, illiterate cultures where people count with their fingers and are very happy. It would be interesting to know how such a society compares to ours in terms of violence, cruelty, and exploitation. What we do know is that a good Western education does not ensure moral rectitude or prevent personal corruption and autocratic ambition. Mussolini studied at the University of Lausanne, Goebbels at Heidelberg, Duvalier at Michigan, Fujimori at Wisconsin, George W. Bush at Yale, Syngman Rhee at George Washington University, Harvard, and Princeton, Richard Nixon at Duke, Carlos Salinas at Harvard, Henry Kissinger at Harvard, Benjamin Netanyahu at Harvard and MIT, Margaret Thatcher at Oxford, and Donald Trump at the Wharton School of Business. More overtly bloody dictators were usually formed in more or less sophisticated military schools. What all of them may have in common is that they relentlessly pursued individual power and succeeded. This is a topic not covered by the STEM curriculum since, as noted before, ethics is taught in the humanities.

There are other questions that STEM ignores but that are fundamental to its dominance. One is the difference between the unexpected and the unpredictable—a difference that helps separate ingenuity from creativity. Ingenuity recombines available ingredients to solve a problem in new and better ways; the result may be unexpected, but it is still predictable. Creativity, on the other hand, deals with the unpredictable and unrestrained generation of new meanings. The distinction is important because the continual stress on applicability and profit in neoliberal society favors ingenuity over creativity.

Illustration at the beginning of Euclid’s Elementa, in the translation attributed to Adelard of Bath, between 1309 and 1316. Source: British Library. License: Public domain.

In the same way that training has usurped the word “education,” ingenuity has now appropriated “creativity.” “Thinking outside the box” is an entrepreneurial buzz phrase that encourages ingenuity in order to bring new ideas into the box. Artists would question not only the limitations of the thinking inside the box but also the actual existence of the box. A politicized artist might even try to identify who created the box and why. The point would be to counteract and destroy the limits it imposes on our thinking.

Besides promoting class and race divisions, our educational system is increasingly designed to train unimaginative technocrats to serve thoughtless consumers. By advancing financial and military interests, these technocrats create ecological disasters—and then expect to be praised for their post-disaster “ingenuity.” And now we have artificial intelligence barging in and possibly taking over many of our decisions.

I’m not particularly informed in these matters, so I went to ChatGPT for help. I figured I could ask ChatGPT about its own intentions and get the type of unvarnished answer that a CEO wouldn’t give me. I asked: “Is artificial intelligence working together with STEM to build a technological society?” The answer was very clear: “Yes, artificial intelligence plays a significant role in collaboration with STEM fields to build and advance technological societies. The integration of AI into STEM disciplines has the potential to enhance various aspects of research, development, and innovation.”

After enumerating seven areas of collaboration, including education and training, ChatGPT finished by stating:

In summary, the synergy between AI and STEM is crucial for building and advancing technological societies. The collaboration enhances the capabilities of STEM professionals, accelerates research and development, and leads to the creation of innovative solutions across various domains.

Fearfully I then asked: “Isn’t this a very one-sided kind of society? Where are the humanities and art in this education?” The answer:

You raise a valid point, and it’s important to recognize the need for a well-rounded and interdisciplinary approach to education and societal development. While the integration of AI and STEM is indeed transformative, a balanced society should also value and incorporate the contributions of the humanities and arts.

The solution ChatGPT offered to this was “STEAM”—adding the letter “A” for “art.” ChatGPT actually had a better interpretation of this than some of the original STEAM proponents, who only saw art as a tool to help technology.

I then asked about how to handle the unexpected and the unpredictabile. For this ChatGPT recommended several strategies, primarily “adaptive learning,” and then added: “While AI models can process large amounts of data, human judgment and intuition remain crucial for assessing complex and novel situations. Combining AI capabilities with human insights can enhance decision-making in unpredictable scenarios.”

This sounds nice and sensible as long as we see AI as a friendly collaborator, which might be true if we are able to maintain the upper hand. But what if not? Then I realized: Who better to ask about this than AI itself? So there I went: “This opens the field for AI dominance. Is there any way to protect human independence from this? Is art a tool that can help in this?”

The answer was: “Art and the humanities, in general, can play a crucial role in safeguarding human independence and providing a counterbalance to the potential over-reliance on AI.” This was followed by a long list of suggestions that, though very reasonable and obvious, I have not yet seen in any academic policy statements. Some of these are:

Incorporating artistic and humanistic perspectives ensures that technology is designed to enhance human well-being and independence.

Art, literature, and philosophy cultivate critical thinking skills. A society that values these disciplines is better equipped to critically assess the impact of AI on various aspects of life.

Artistic expression and creativity are uniquely human qualities. While AI can generate art, it lacks the depth of human emotion and context. The preservation and celebration of human creativity can be a powerful reminder of what makes us distinct from machines.

Concerns about AI dominance often revolve around the potential dehumanization of society. Art has the ability to resist dehumanization by emphasizing the emotional, aesthetic, and cultural dimensions that make us [sic] human.

Art and literature are powerful mediums for developing emotional intelligence. Understanding and managing emotions are essential aspects of human independence, and emphasizing emotional intelligence can be a counterbalance to the purely rational and algorithmic nature of AI.

In summary, art and the humanities serve as powerful tools for preserving and promoting human independence in the face of advancing AI technologies. By emphasizing the human experience, fostering critical thinking, and advocating for ethical considerations, society can ensure that AI complements rather than dominates our lives.

Recently a lawyer was reprimanded because he told a judge, “See you next Tuesday.” Like the judge, I initially took the lawyer’s statement as harmless. It never occurred to me—or to the judge, until somebody pointed out to her the coded message—to read the statement as C (see) U (you) N (next) T (Tuesday). Maybe art’s new function, then, besides dealing with mystery, the unknown, and the unpredictable, is to develop a code that looks harmless to AI but conveys secret meanings only understandable to humans. This would be a new literacy to be acquired during schooling, a skill more important than reading, writing, and numeracy—that is, if we want to survive as the humans we believe we are. I assume that the term “humanities” is derived from this belief. Unfortunately, the educational system has never focused on that connection, otherwise the humanities would be taught in their own distinctive way, rather than in a way that emulates the hard disciplines. Even in their distorted teaching, what does the removal of the humanities from the center of modern education mean for our responsibilities as human beings? According to ChatGPT:

The removal of the humanities from education can have significant implications for our sense of humanity and the responsibilities that come with it … Here are some potential consequences of removing the humanities from education: Loss of Cultural Understanding, Diminished Critical Thinking Skills, Impact on Moral and Ethical Development, Reduced Creativity and Innovation, Narrowed Perspective on Humanity, Weakened Communication Skills, Impact on Citizenship and Civic Engagement.

It’s depressing that this had to come as an AI insight instead of a basic part of everyday schooling.

J. A. Aunión, “Educación quiere menos asignaturas para centrar la anención de los alumnus,” El Pais, September 3, 2012 →.