Homelessness is coming to be the destiny of the world.

—Martin Heidegger1

Can we continue to regard, as Husserl does, the Chinese, Indians and Persians as “anthropological types of humanity,” and these societies of the past as devoid of problematicity, as Patočka suggests, or as mere private economies, as Hannah Arendt asserts? In my view, it is urgently necessary at the start of the twenty-first century for philosophers to develop the historical sense that Nietzsche said they so sorely lack, and to recognise that these discourses on Europe are no more than an ideological construct and the result of a conception of the world that stems from colonialism, with which, unfortunately, the name Europe remains closely linked.

—Françoise Dastur2

In the eighteenth century, philosophy was described by Novalis as a kind of suffering—a homesickness and a longing to be at home: “Philosophy is actually homesickness—the desire to be everywhere at home [Die Philosophie sei eigentlich Heimweh—Trieb, überall zu Hause zu sein].”3 The Heim- here is not only “home,” but more significantly invokes a “homeland” (Heimat). This longing for Heimat became an omnipresent phenomenon during the process of colonization and modernization. But during the same period, home became a mere geographical location on one particular celestial body (among countless others), and the importance of a geographical location began to be evaluated in terms of its abundance of natural resources and its economic potential. One may, like Heidegger, remember the pathway of the Heimat in summer, the old linden trees gazing over the garden wall—a pathway that shines bright between growing crops and waking meadows.4 But today the small village is full of tourists who want to visit the Heimat of a famous philosopher, and new infrastructure is being built to accommodate the demands of these visitors from all over the world. Alas, the Heimat ceases to be what it once was.

Yessica Yana, Bolivia’s first indigenous Aymara woman drone pilot.

Economic and technological development has continued to alter the landscape of these small villages, and in even more radical ways with advances in the automatization of agriculture. Today many rural areas use drones and robots to fully automate the processes of sowing, ploughing, harvesting, packing, transportation, etc. Farmers no longer resemble the old lady who Heidegger once imagined when seeing Van Gogh’s painting of the “peasant’s shoes.” Today’s farmers are young, dress in smart suits, and control operations with their iPads. The village remains, as do the linden trees and meadows, but the surrounding area is gentrified with expensive cafés and hotels, and the route of Heidegger’s pathway is intersected by the vectors of drones and robots. This lends an even more hysterical tone to the philosopher’s exclamation when we read it today:

Man’s attempts to bring order to the world by his plans will remain futile as long as he is not ordered to the call of the pathway. The danger looms that men today cannot hear its language. The only thing they hear is the noise of the media, which they almost take for the voice of God. So man becomes disoriented and loses his way. To the disoriented, the simple seems monotonous. The monotonous brings weariness, and the weary and bored find only what is uniform. The simple has fled. Its quiet power is exhausted.5

The longing for Heimat is a consequence of a sense of being away from home; the nearest and the remotest to us, as Heidegger says, it is so close and so far that we fail to see it.6 One might well continually travel from continent to continent. However, there seems to be only one home, to which one would finally return when one feels tired and no longer wants to move. Over past centuries, the conception of the home as the place of natality has been altered owing to the increasing prevalence of immigrants and refugees. From the standpoint of Heimat, immigration is an uprooting event in which the plant has to search for a new soil in which to implant itself. However, even if the new soil provides the appropriate nutrients, the immigrant’s memory of Heimat always reminds one of a past that is no longer and will never be again. And, being foreign, they will also have changed the existing soil by bringing about a new ecological configuration. The moderns begin to sense their homelessness upon the earth, as described by Georg Trakl in his poem “Springtime of the Soul”:

Something strange is the soul on the earth. Ghostly the twilight

Bluing over the mishewn forest, and a dark bell

Long tolls in the village; they lead him to rest.7

This feeling of Heimatlosigkeit (homelessness) haunted thinkers of the twentieth century, for whom the most important philosophical task became that of shedding light upon a Heimat to come. The soul is a stranger on the earth, where any place is rendered unheimisch (unhomely). For Heidegger, homecoming is an orientation (Erörterung) which defines a locality as a root without which nothing can grow. However, when homelessness becomes the destiny of the world, the soul is comparable to a houseplant, in the sense that it could be grown and taken anywhere on the planet. The homogenization of the planet through techno-economic activities has created a synchronicity of social phenomena. Rituals and heritage sites become fodder for tourists, with mobile phone cameras replacing the senses of the eyes and the body. The soul’s relation to the world is mediated through digital apparatuses and platforms.

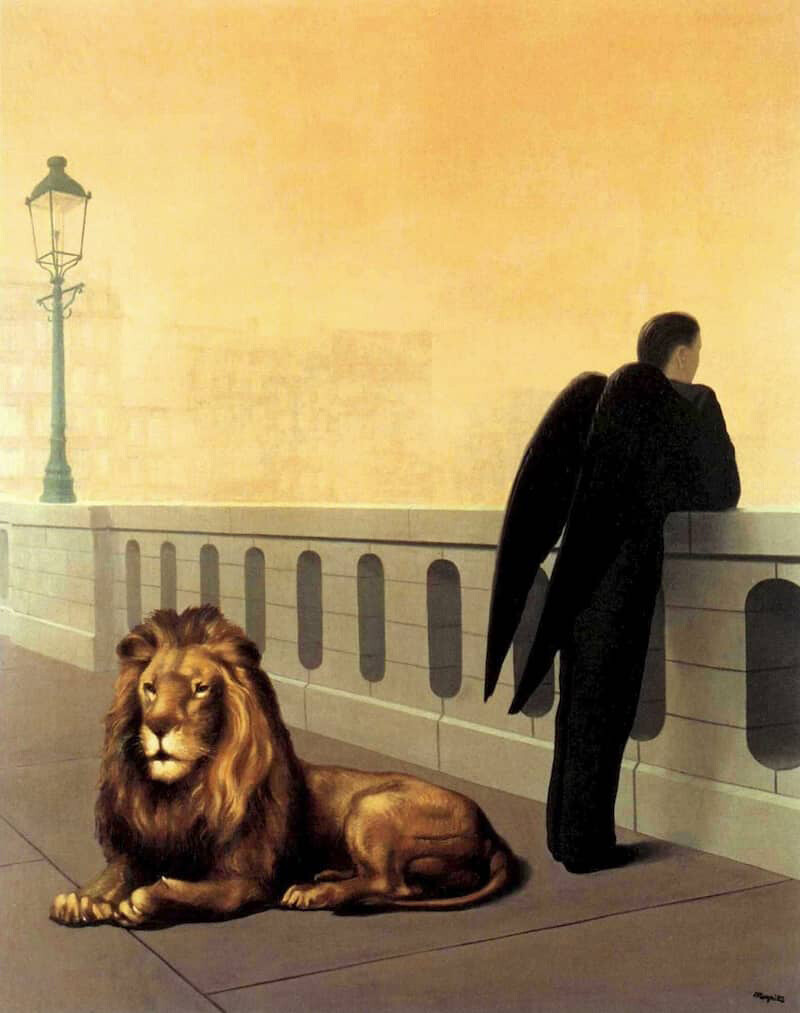

Rene Magritte, Homesickness, 1940.

However, memory is not simply a cognitive entity in the mind. The interiority of the body also struggles to fully adapt to new environments. Food can then become the strongest reminder of a past, like the madeleine crumbs dipped in lime blossom tea that Proust described in his In Search of Lost Time. This experience is even more common when one lives abroad. We might not be able to identify such an experience in the writings of Heidegger, since the philosopher never travelled outside of Europe, but it was described by his foreign students. Keiji Nishitani, one of the representatives of the Kyoto School, spent two years in Freiburg with Heidegger between 1937 and 1939. On a September day in 1938, together with two other Japanese students, Nishitani was invited to dinner by Fumi Takahashi, the niece of Kitaro Nishida, who had just arrived in Freiburg in April 1938 to study with Heidegger.8 Takahashi cooked a Japanese meal with ingredients she had brought from Japan. Nishitani, who at the time had been living on a German diet for more than a year,9 upon tasting the bowl of white rice felt something extraordinary, as James Heisig remarked: “Eating his first bowl of rice after a steady diet of Western food, [Nishitani] was overwhelmed by an ‘absolute taste’ that went beyond the mere quality of the food.”10

Imagine if Heidegger had taught in Japan: Would he have been able to put Schwäbische Küche out of his mind and body while eating sashimi and sushi? Probably not. In the case of Nishitani, the Heimweh arrived when shirogohan instead of Kornbrot stimulated his taste buds, but the sensation also went beyond his taste buds and affected his whole body.11 Heimat does not concern what one learns of one’s nation in a history lesson, but rather is something inscribed in the body as one of its most intimate and inexplicable parts. This experience of being Unheimlich (uncanny) only reinforces the longing for Heimat.12 In his memoir, Nishitani concludes of this meal:

This same experience also made me think about what is called “homeland,” which is fundamentally that of the inseparable relation between the soil and the human being, in particular the human being as a body. It is “the nonduality of soil and body” of which Buddhism speaks. In my case, homeland is the “Land of Vigorous Rice Plants”: a soil fit for rice and a people that has found the mainstay of its livelihood in rice cultivation. From generation to generation, my ancestors have had rice as their staple food. The special ingredients of the land called Japan are transferred to the special ingredients of the rice called “Japanese rice,” and through eating rice, they are transferred to the “blood” of our ancestors, and that blood flows through my body. Perhaps from long ago, the vital connection between the countless people who were my ancestors, the rice, and the land has always been the background of my life and is actually contained in it. This experience made me remember something that I had usually forgotten.

The bowl of white rice is not just food that satisfies biological need, negating the sense of hunger; it is also a mediation between body and Heimat. Taste is associated with the Fatherland via the tongue. It is no surprise, then, that after returning to Japan, Nishitani actively participated in the movement of “overcoming modernity,” which gathered historians, music critics, philosophers, and literary scholars to reflect upon how to overcome the domination and the decadence of Europe. To them, European modernity presented itself as a fragmenting force, its separation of culture into religion, science, and politics (or more precisely democracy) destroying the unified worldview which, in Japanese and Chinese culture, held together heaven, earth, and the human.13 However, even as this European nihilism continued to spread across the entire globe, Europe itself was declining. The Europeanization of the East then also threatened to introduce into the East the same decadence as the West. In his book Self-Overcoming Nihilism (a collection of lectures on nihilism delivered in 1949), Nishitani commented on Karl Löwith’s essay “European Nihilism” to ask what European nihilism meant to Japan:

European nihilism thus brought a radical change in our relationship to Europe and to ourselves. It now forces our actual historical existence, our “being ourselves among others,” to take a radically new direction. It no longer allows us simply to rush into westernization while forgetting ourselves.14

The twentieth century was a century of orienting (erörteren) Heimat within the planetarization of European modernity. Although he made it possible for Nishitani and Tanabe to study abroad in Germany, Kitaro Nishida himself didn’t have the chance to do so when he was young. Yet in his writing one can also find this search for Heimat—which for him bears the name of East Asia, or tōyō. This longing for Heimat continued to intensify because modernization implied the destruction of the old and the creation of something that is global. The destruction of villages and forests for the sake of building new infrastructure, the renovation of urban spaces in order to accommodate tourism and foster real estate development, the increasing immigrant and refugee population—all of these created a feeling of being unheimisch. And then after Europeanization came Americanization or Americanism, of which Heidegger and his Japanese students were already very conscious, and which they regarded as the continuation of Europeanization through a planned planetarization.15 In “What are Poets For?,” an essay dedicated to Rilke, Heidegger cited the poet’s letter to Witold Hulewicz in 1925 on the Americanization of Europe:

For our grandparents a “house,” a “well,” a familiar steeple, even their own clothes, their cloak still meant infinitely more, were infinitely more intimate—almost everything a vessel in which they found something human already there, and added to its human store. Now there are intruding, from America, empty, indifferent things, sham things, dummies of life [Lebensattrappe] … A house, as the Americans understand it, an American apple or a winestock from over there, have nothing in common with the house, the fruit, the grape into which the hope and thoughtfulness of our forefathers had entered … Things living, experienced, and communing are going under and cannot be replaced. We are perhaps the last ones who will have known such things.16

The ultimate problem for Heidegger was inhuman technology.17 Modern technology is the end product of European nihilism, which began with the forgetting of the question of Being and the effort to master (beherrschen) beings. The interposition of technology into the world has produced a generalized homelessness, and has blocked the path toward the questioning of Being. Heimatlosigkeit is tantamount to the Heillosigkeit (unholiness or hopelessness) of the Abendland, the evening land, in the dawn of Americanism and its imperial force, supported by its planetary technologies. Again in “What are Poets For?” we read Heidegger’s clearest lament on this matter:

The essence of technology comes to the light of day only slowly. This day is the world’s night, rearranged into merely technological day. This day is the shortest day. It threatens a single endless winter. Not only does protection now withhold itself from man, but the integralness of the whole of what is remains now in darkness. The wholesome and sound withdraws. The world becomes without healing, unholy. Not only does the holy, as the track to the godhead, thereby remain concealed; even the track to the holy, the hale and whole, seems to be effaced.18

In the age of technology, Being withdraws from the world; what is left is a world of beings decomposed into atoms and feedback loops. This uprooting (Entwurzelung), for Heidegger, is no longer a phenomenon of the West. It has gone beyond Europe through its planetary technology. One might recall here Tolstoy’s criticism voiced in 1910, during his last years, when the writer said that medieval theology or the Roman moral inheritance only intoxicated a limited amount of people, but today’s electricity, trains, and telegraph have intoxicated the whole world.19

Australian troops using a Mance mk.V heliograph in the Western Desert in November 1940. License: Public Domain.

These technologies are carriers of Western thinking, Western models of individuation, modes of production, and a Western libidinal economy. Economy first of all consists in exchanges of technics and technicity that short-circuit the process of production: for example, the tool we buy in the market is produced via a complex technical system, and we can simply use it without having to learn how to make it ourselves. But at the same time, the economic system demands technology as its medium of exchange, ranging from cargo transportation to high-speed trading. In his lecture “What is Called Thinking?” Heidegger mocks “logistics” as the most recent and fruitful realization of “logic,” which in many Anglo-Saxon countries, he says, is considered the “only possible form of strict philosophy.”20

In the twenty-first century, we can easily sense that this process of destruction and recreation is only accelerating rather than slowing down. The longing for Heimat will only be intensified instead of being diminished; the dilemma of homecoming can only become more pathological. In fact, two opposed movements are taking place at the same time: planetarization and homecoming. Capital and techno-science, with their assumed universality, have a tendency toward escalation and self-propagation, while the specificity of territory and customs have a tendency to resist what is foreign.

Homecoming is being challenged in very concrete ways today. When we look at the housing problem in Europe in 2023, the number of people who cannot afford to rent a proper apartment for their family has sharply increased. The increase in property prices over the past decade is alarming. This may continue until a certain moment when the bubble bursts, and then those who are paying for mortgages will be in unmanageable debt. Global real estate speculation and the neoliberal economy have created a situation of Heimatlosigkeit that challenges both ethos and ethics. Real estate speculation will continue to drain the creativity and potential of individuals.

The years 2023–2024 have been marked by a feeling that the world has begun to fall apart. On the one hand there is the Russia-Ukraine War—a constant reminder of the insecurity of Europe and the cause of a global logistical catastrophe. At the moment of writing, the Israel-Hamas War appears to be far more brutal and inhuman, and displays clear indications that another world war could erupt at any time. On the other hand, rapid technological acceleration, emblematized by ChatGPT, invokes the sentiment that the human will be rendered obsolete by machines very soon. Deracination is accelerated by technology because machines are capable of learning in order to outdo human competitors. Well beyond the triumph of AlphaGo, which was limited to the Go game, AI has now penetrated into almost all domains of everyday activity and is disrupting them, turning them upside down. This technological, ecological, and economic progress clearly promises us some kind of apocalypse.

This ruin caused by techno-economic planetarization calls for a homecoming, a return to the ethos. The world is once again being seen from the standpoint of Heimat, but not from a planetary perspective nor that of world history. Frustration and discontent over no longer being at home express themselves as wars against outsiders, with immigrants and refugees the first targets of discrimination and hatred. Reactionaries and neo-reactionaries want to return home—to a home that was once “great,” and which one must make great once again. According to some, especially those who believe in the “deep state,” the death of community, described in terms of a “Great Replacement,” also means the end of the individual, since by that point Europe will be “blackwashed.”21

The process of planetarization has produced a global disorientation. Does this mean that we need to reconstruct the concept of Heimat? Does this call for another Blut und Boden? Can the return to Heimat help us to escape this process of increasing alienation? We already know the answer. For the twentieth century was a century of searching for Heimat. The philosophical movement associated with it was reactionary and dangerous. Everyone certainly needs a “home” or a locality where they feel safe and at ease. But this home is not necessarily the same as the search for Heimat, or fatherland, found in literature beginning in the eighteenth century and which persists in the reactionary online tracts of today.

To be continued in “Planetarization and Heimatlosigkeit, Part 2”

Martin Heidegger, “Letter on Humanism,” in Pathmarks, ed. W. McNeill, trans. F.A. Capuzzi (Cambridge University Press, 1998), 258.

Françoise Dastur, “L’Europe et ses philosophes: Nietzsche, Husserl, Heidegger, Patocka,” Revue Philosophique de Louvain 104, no. 1 (2006): 8.

Novalis, Notes for a Romantic Encyclopedia: Das Allgemeine Brouillon, ed., trans. D. W. Wood (SUNY Press, 2007), 155.

Martin Heidegger, “The Pathway,” trans. T. F. O’Meara and T. Sheehan, in Heidegger: The Man and the Thinker, ed. T. Sheehan (Precedent, 1981), 69.

Heidegger, “The Pathway,” 70.

Julian Young, “Heidegger’s Heimat,” International Journal of Philosophical Studies 19, no. 2 (2011): 285.

Cited in Martin Heidegger, “Language in the Poem: A Discussion on George Trakl’s Poetic Art,” in On the Way to Language, trans. P. D. Hertz (Harper & Row, 1971), 198.

See Michiko Yusa, Zen & Philosophy: An Intellectual Biography of Nishida Kitarō (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2002), 243.

Nishitani wrote about this experience in a short article published in a magazine thirty-three years after this meal. The article bears the title “The Experience of Eating Rice” (飯を喰った經驗). It was later republished in the collected work of Nishitani. See Keiji Nishitani, “飯を喰った經驗,” in NKC 20 (西谷啓治著作集) (Shobunsha, 1990).

James Heisig, Philosophers of Nothingness: An Essay on the Kyoto School (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2001). See also Nishitani, “The Experience of Eating Rice,” 197: “强ひて言へば絶對的な旨さである。”

Nishitani, “The Experience of Eating Rice,” 197: “舌の上では なく全身で感ずる 旨さである。”

In his lecture course on Hölderlin’s Hymn “The Ister,” Heidegger reintroduces the term unheimisch, which is now much less used than unheimlich in German. Heidegger wants to reassociate the meaning of unheimisch (unhomely, or not being at home) with unheimlich (uncanny, strangeness). See Martin Heidegger, Hölderlin’s Hymn “The Ister” (Indiana University Press, 1996); Hölderlins Hymne »Der Ister« GA 53 (Vittorio Klostermann, 1993).

See Nishitani’s talk “My View on ‘Overcoming Modernity’” (「近代の超克」私論) in Overcoming Modernity (近代の超克), ed. Tetsutarō Kawakami and Yoshimi Takeuchi (Fuzambo, 1979).

Keiji Nishitani, The Self-Overcoming of Nihilism, trans. G. Parkes with S. Aihara (SUNY Press, 1990), 179.

Martin Heidegger, “The Age of the World Picture,” in The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, trans. W. Lovitt (Harper and Row, 1977), 153. “‘Americanism’ is itself something European. It is an as-yet uncomprehended variety of the gigantic, and the gigantic itself is still inchoate, still not yet capable of being understood as the product of the full and complete metaphysical essence of modernity. The American interpretation of Americanism by means of pragmatism still remains outside the metaphysical realm.” In this sense, Americanism is no different from Sovietism, as announced by Heidegger in Introduction to Metaphysics as follows: “This Europe, in its ruinous blindness forever on the point of cutting its own throat, lies today in a great pincers, squeezed between Russia on one side and America on the other. From a metaphysical point of view, Russia and America are the same; the same dreary technological frenzy, the same unrestricted organization of the average man.” Martin Heidegger, An Introduction to Metaphysics, trans. R. Mannheim (Anchor, 1961), 38–39.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Witold Hulewicz, November 13, 1925, Briefe in Zwei Bänden (Insel Verlag, 2 vols., 1950), vol. 2, 376–77; quoted in Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought (Harper and Row, 1971), 110–11.

Gotthard Günther, “Heidegger und die Weltgeschichte des Nichts,” in Nachdenken über Heidegger: eine Bestandsaufnahme, ed. U. Guzzoni (Gerstenberg, 1980), 83.

Heidegger, “What are Poets For?,” 115.

See Karl Löwith, “Der europäische Nihilismus: Betrachtungen zur geistigen Vorgeschichte des europäischen Krieges,” in Weltgeschichte und Heilsgeschehen: Zur Kritik der Geschichtsphilosophie (J. B. Metzlersche, 1983), 497.

Martin Heidegger, What is Called Thinking?, trans. F. D. Wiieck and J. G. Gray (Harper & Row, 1968), 21.

For example, in the work of the conspiracy theorist and white nationalist Renaud Camus.

From Post-Europe, by Yuk Hui (Urbanomic/Sequence Press, 2024), 144 pp., $17.95, ISBN 979-8-9854235-1-8. Distributed by the MIT Press.