Unauthorized Repair

“Whatever broken phone you have, we can fix it here!” Xiaole declares his repair superpower when we first meet. He goes on to demonstrate a technique called “flying wires.” “You see, I need a bit of wire to get around this broken part so that the rest of the circuits can still work,” he explains as his hands move seamlessly across a smartphone motherboard, a wire coil, a soldering gun, and some tweezers, all under a well-used microscope whose unassuming presence feels more like an old family cooking pot than a pristine lab machine.

Right next to Xiaole, hunched over the same narrow desk cramped with electronic tools and parts, another technician, Hu, is winding the ends of a thin steel string around two short pencils. He then picks up a phone with a shattered glass screen and puts it on a box-shaped device with a palm-sized platform that looks like an elaborate art display pedestal—except plugged in. It is for heating and melting the glue between the touchscreen and its glass shield. While the phone heats on the platform, Hu rhythmically zigzags the steel string, held straight with a pencil at each end, across the surface of the phone, under the broken glass pieces but above the display. He uses pencils because “otherwise the string would cut into your hands,” he says, which would be “much worse than paper cuts.”

In another corner, a debate ensues.

“Try not to touch the motherboard before eliminating all other possible causes,” a client says to technician Ling, then goes on: “I think the issue is probably something really minor.”

“But I’ve tested everything—all three camera modules, the lens, the flex cable,” replies Ling, pointing his tweezers at the malfunctioning phone in question.

“Have you tried swapping the facial recognition module?” says another technician, Fo, turning around to advise and passing over a small black spare part. “Here, try this.”

Ling takes the component and works busily under his microscope for a few minutes.

“Oh it worked!”

“See! I’ve seen this a hundred times,” says Fo proudly. “A lot of camera issues are related to facial-recognition stuff.”

“Cool, now you get to sell your part thanks to me,” replies Ling. The two later split a $3 profit from the component.

This all takes place inside a tiny repair stall approximately the size of a New York City newsstand. It is co-rented by seven technicians who share two long, narrow desks set against each side wall as their collective work stations. What little open space is left in the middle stands in as a de facto storefront, for a nonstop flow of clients to stop by, check in, or drop off their devices to be repaired. Nested in a bustling four-story indoor market densely packed with numerous similar shops, the stall marks the beginning of our weekslong fieldwork into the world of repair.

When offline wisdom-sharing doesn’t take, there’s the internet. A whole genre of smartphone repair videos circulates on China’s social media, where professional and amateur technicians produce-consume content, including technical walkthroughs, personal workflows, and eye-catching hacks. Social media is becoming an inevitable part of the job. “Many of our orders come from online now, our own followers or ecommerce apps,” relates Tao, another technician. “Like a friend of ours—he got trending on TikTok for some reason and he’s getting so many customers from there!”

In a popular video, repair influencer and technician A-Bin proudly declares: “I’m sorry, Apple. Huaqiangbei has let you down once again. You can encrypt it. We can crack it!” (“你加密,我破解!”) In the video, he explains how independent repairers—those without Apple’s seal of approval—work around iPhones’ encryption of facial-identification modules. Apple’s encryption, which disables some functionality after certain third-party repairs such as screen replacement, has been notorious in the global repair communities as epitomizing the low repairability of Apple products and their increasing use of vectoral blocks against hardware repairs.1 “This means for that iPhone 13 in your hand, if its screen is broken, you can only replace it at authorized stores. You can’t get it fixed elsewhere. Now, isn’t that messed up?” exclaims A-Bin, calling the repair block “gross.” He then shows how unauthorized repairers bypass the block by moving an encryption-firmware chip from the original screen to the repair screen. At the end of the video, A-Bin turns to the camera and asks, “How about that friends! Isn’t this very ‘Huaqiangbei’?”

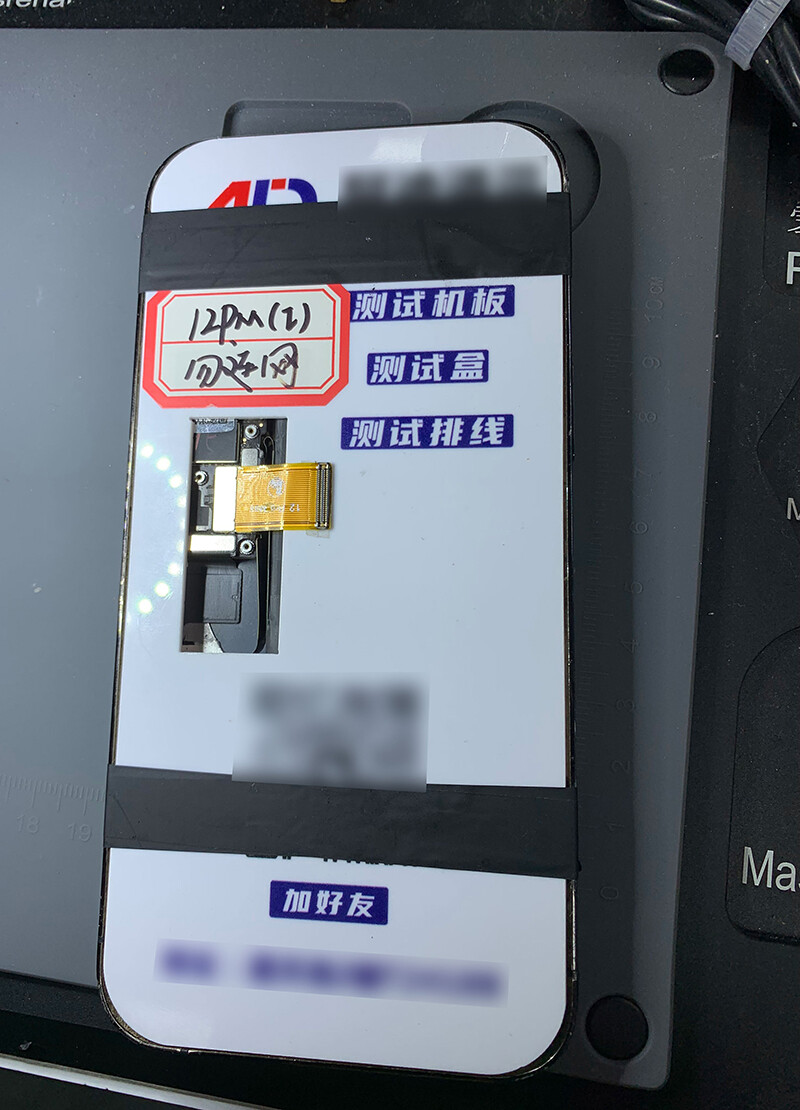

A self-made diagnostic tool to test screen functionality, repurposed from a display-less smartphone, 2024. Photo: Yifan Wang.

Huaqiangbei (华强北) is the name of the district where these repair technicians and their stalls—known as “one-meter counters” (一米柜台) for their compact size—are based. It sits at the center of Shenzhen, a city emblematic of China’s emergence as the world’s factory and the concurrent ascension of a global vectoralist class dictating the world’s factory from afar. While factory-owning capitalists take charge of production in local sites, information-owning vectoralists command proprietary routes, networks, and vectors of information over globalized production: brands, patents, design, logistics, and so on. The latter orders the former over the what, where, and how of production. The term “Huaqiangbei” literally refers to the northern part of an avenue called “China-Strengthening” (华强路). It is an area handpicked by local officials to become one of the first industrial district experiments for the Communist Party’s efforts to redefine socialism with Chinese characteristics.2 Dubbed the Silicon Valley of hardware, the mainstay of Huaqiangbei’s economy is cycle after cycle of the latest industrial and consumer electronics—from diodes to microcontrollers, from radios to DVD players, from black brick phones to sleek silver laptops. Behind the upgrading of hardware is a kind of upgrading of people: construction soldiers of the Third Front defense infrastructure get relocated to build export-oriented factories.3 Former peasants disintegrated from socialist rural communes transform into migrant electronics workers. Urban workers laid off from iron-bowl jobs become self-employed entrepreneurs and backpack traders (背包客).

The official story of Huaqiangbei and Shenzhen is a narrative of China’s economic miracle and socialist reform success. The messy, inconvenient fact that whatever is made will need, at some point, to be repaired rarely gets a mention. But things degrade just as they upgrade. That’s where the repairers come in. A relatively small part of the Huaqiangbei community—where most people are engaged in the trading and manufacturing of new devices—repairers are concentrated in two Akihabara Electric Town–style electronics wholesale market buildings. These lively, hectic malls specialize in second-hand phone trading and refurbishing, creating a niche demand for repairers and carving out a small place for broken objects amid Huaqiangbei’s general theme song of the new. This is a place where everything looks like a mesmerizing mishmash of a Jodi game modification, headline-grabbing shanzhai handphones, and Deng Xiaoping–style grassroots entrepreneurship.4 Technicians in stall after stall, together with their myriad self-developed tools, encryption-hacking devices, and informally sourced components, look at the “warranty voided if removed” warning with a side eye.

The first step to repair any phone is to open up the casing. Guarded by water-resistant adhesives, the hardware case is the first line of defense against any “unauthorized modification” that dare challenge the Big Tech monopoly of branded devices, proprietary codes, information black boxes, exclusive expertise, and planned obsolescence. To penetrate it is no easy feat. Huaqiangbei repairers have figured out a sneaky trick involving a hair dryer, a razor blade, industrial alcohol, and a guitar pick—the unauthorized repairers’ electronic millet and rifles wielded against today’s “paper tigers.”5 With these tools, they wage a kind of people’s war inside the smartphone, against the state-of-the-art weapon of the vectoralist class known as digital rights management—the corporate euphemism for protecting privatized information and proprietary hardware through technical means.6 As A-Bin says: “If they can encrypt it, we can crack it.”

Despite the repairers’ technical imaginations and socioeconomic contributions, they remain marginalized. Among Huaqiangbei’s tireless hustlers, the role of a repair technician is not a coveted one. “If I could sell phones, I’d never get into repair!” laments A-Xiang. Repair was supposed to be just a temporary gig, a stepping stone to get his foot in the door. Sales is the ultimate goal, a more lucrative business with little cap on profit and scale. “If I sit here and make repairs nonstop all day, I could get a dozen or maybe twenty jobs done, tops,” says A-Xiang. “But if I sell phones, the sky’s the limit.”

The repairers’ marginalization is also evident in terms of topography. The two repair markets are located in the lesser-known parts of Huaqiangbei, which attract much lighter consumer foot traffic than the district’s famed flagship malls right next to subway exits. Within these buildings, repairers usually set up shop at the outer corners on the higher floors, where stalls are largely hidden from shoppers’ view and therefore cost less to rent.

“This business of repair is ultimately only viable in our third-world countries,” says A-Xiang. “Look at the foreigners. Have you seen those videos where people test smartphones by shooting bullets at them?” He goes on: “They can’t be bothered with repairs. So, their unwanted phones end up finding their way to us.”

Authorized Repair

A-Xiang is only partly right. If the overdeveloped world lacks a vibrant repair businesses, it’s not entirely for lack of interest. In the US, for example, independent repairers are constantly besieged by a slew of practical difficulties: customs seizures of imported components, forbidding prices for the complex equipment necessitated by newer devices, and the fast-changing cycles of specialty accessories.7

Alternatively, repairers in the overdeveloped world could always buy their way out of these troubles and obtain “service authorization” from brand owners—e.g., Apple itself. The authorization, typically not bought with merely a one-time payment, depends on a repairer’s ability to consistently purchase premium-priced parts and accessories from the brand corporation, share operational data, meet strict financial requirements, and consent to regular performance reviews. In return, the authorized repairer gets component supplies, training courses, device data, repair-related codes, and more importantly access to an exclusive market of customers enclosed in what financial analysts and business executives like to call an “ecosystem.” This mesh of proprietary hardware and software meticulously manages the compatibility, usability, and repairability of each product throughout its life cycle, establishing multidirectional vectors for watertight surplus extraction and preventing any potential leakage to external parties like an unauthorized repair shop. The authorization of repair is the blockade of repair.8

A typical repair stall in Huaqiangbei, 2024. Photo: Yifan Wang.

Independent repairers in the overdeveloped world have lately gained ground in challenging these systems of enclosure, primarily through the double-edged sword of state legal apparatuses. In the US, multiple states have passed right-to-repair legislation. Several class-action suits against John Deere’s repair restrictions are moving forward. Biden has issued an executive order calling for repair rights. All of this occurs under Biden’s broader agenda that aims to boost employment and step up government investment in key industries (including clean energy), as well as a push by more progressive politicians and activists for climate action and stronger social welfare. A Green New Deal?9 Or an emerging political-economic structure that can’t quite be described by modifying the modifier?

At the center of this new structure is a mode of (re)production that seeks to instrumentalize, control, and commodify broken resources and their repair. There have been centuries of seemingly limitless growth fueled by the colonial extraction of the “seven cheap things”—nature, money, labor, care, food, energy, and lives—and beyond.10 This extraction can’t go on forever, as these cheap things get used up, worn out, and broken down, threatening to turn assets into stranded assets.11 It is now impossible for either the ruling classes or the productive classes to look away from brokenness and repair. If the question for the newborn vectoralists at the turn of the millennium was how to make endless information appear scarce, the question now becomes how to sustain endless information and its ever expanding “stack” on a finite planet increasingly falling apart.12 As Wark puts it: “Quite simply, we have run out of world to commodify.”13

One solution, of course, is to look for more “worlds” to commodify. Space exploration, vertical farming, land reclamation, underwater data centers all fall under this category.

Another solution is to invent a new mode of commodification, production, reproduction, accumulation, and extraction based on repair. The carbon offset industry seems the quintessential example. Step one: identify a massive political-economic opportunity in repairing carbon distribution on earth. Step two: invent a new asset form to seize this opportunity—the carbon emission credit. Step three: occupy necessary natural-cultural resources to control this asset. Step four: start producing, reproducing, buying, selling, lending, borrowing, holding, or shorting it.14 In the first quarter of 2024, Tesla made nearly 40 percent of its total profit from such transactions.15 A new antagonism grows in the material-social-political-economic structures of class society—an antagonism over relations of repair: who gets to take natural control (such as physical possession and access) and cultural control (such as pricing mechanisms, new property rights, state regulations) of broken and repaired things?

Wark: “For a long time, it seemed like a critical gesture to insist that reality is socially constructed. Now it seems timely to insist that the social is reality constructed.”16 Also, it seems impossible to utter words like “reality,” “society,” “culture,” and “nature” without an uneasy sense of inaccuracy and the need to make up awkward phrases like “the material-social-political-economic.”

Social and material (physical, chemical, biological, and beyond) processes have always existed side by side in forming naturecultures.17 And intense struggles have always been fought over where the cut between nature and culture is made.18 The Israeli state has long used climate data to justify displacement, and it is now blatantly destroying solar panels in Palestine that were set up as civilian energy infrastructure independent of Israeli state control.19 Harlem condo developers displace low-income residents with the green wave of environmental gentrification.20 US national parks evict Indigenous communities to create “natural wilderness.”21 Oil companies conveniently adjust calculations of the earth’s oil reserves to suit business purposes.22 These struggles are absorbing ever more parts of the world. For a long time, it might have been possible to forget about the “nature” part of naturecultures so long as one was not a survivor of Hurricane Katrina, or the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, or the 2022 heat waves in China.23 Today, it’s becoming glaringly clear that natures and cultures constitute each other, and everyone is on the line, if unevenly so.

In its broadest sense, “repair authorization” is the ruling classes’ attempt to prevail in this new antagonism over broken resources and their repair. Just like vectoralization has swept across primary, secondary, and tertiary production with seed patents, industrial software, and food-delivery apps, repair authorization—still a nascent tendency—imposes itself onto a variety of production and reproduction activities. Electronics repair authorization regimes regulate flows of used commodities to manipulate sales of new commodities. Renewable energy corporations privatize repairable energy sources and turn them into new commodities.24 Vectoralist-led investments in agri-technologies seek to restore farming productivity as land fertility breaks down under climate change.25 Reverse logistics recovers surplus extraction opportunities for used commodities; Intel is planning to make over $300 million by 2025 through such repairs.26 Wellness industries commodify communal healing practices to repair human bodyminds—for a price.27 The forefront of surplus extraction travels full circle from the information vectors of “third nature,” back to first-nature resource recovery, recycling, and repair, as well as second-nature social and culture damage control.28 The ruling classes previously simply exported the metabolic rift’s ugly consequences to the underdeveloped world.29 Now, they want to orchestrate the repair of this widening rift on their terms.

Reproduction

Repair moves from the backstage of productivist history into the spotlight. Forces of reproduction become forces of production. Karl Marx: “Every social process of production is, at the same time, a process of reproduction.”30 Nancy Fraser: “Social reproduction is an indispensable background condition for the possibility of economic production in a capitalist society.”31 Eli Lilly: “For many of our products, we hold other patents on manufacturing processes, formulations, or uses that may extend exclusivity beyond the expiration of the compound patent.”32 The vectoral production of patents turns on the vectoral reproduction of patent extensions.

Just like most theories of production, most theories of reproduction suffer from an obsession with the eternal critique of eternal capital. Examples include accounts of the repressive and ideological reproduction of capitalism’s subjects.33 Or the gendered reproduction of laborers and labor power.34 Or the cultural reproduction of class relations through education and taste.35 Or the political-economic reproduction of capital accumulation.36 However reproduction is analyzed, in these approaches, eternal capital is seen to persist.

But today, when Foxconn shareholders and their numerous capital-heavy factories find their fortunes dependent on factory-less, asset-light vectoralist corporations such as Apple and Microsoft, what is being reproduced is clearly not only, not even primarily, capitalism. Yet even as the vectoralist class ascends above the capitalist class, even as new ruling classes emerge and incumbent elites cede partial power, the hierarchical character of the world’s naturecultures remains more or less intact.

Perhaps this is why critical theorists have been so keen to cling to the word “capitalism” as a placeholder for the seemingly immortal existence of hierarchical class relations despite decades of revolutions and counterrevolutions. After all, while Foxconn’s annual profit rate of 2 percent makes the lives of its owners a bit harder than Apple shareholders, with their 25 percent margin, both still have so much more power than the 99 percent.37 And despite all the talk of the fall of the king and the church, royal families and Catholic popes remain firmly within the ranks of global power elites in this three-dimensional chess game of our time.38 Both residual and emergent forms of ruling-class power flank the rule of a capitalist class. But whatever power reshuffles within the ruling classes, the existence of hierarchical domination stays largely untouched.

Outside one of the busiest second-hand phone markets in Huaqiangbei, 2024. Photo: Yifan Wang.

The grand narratives of various revolutions for and against capitalism are well known.39 But when capitalism is being superseded by something worse, it’s clear capital is not the only and ultimate enemy. Class society is. What if our stories, instead of starting with capitalism, started from the emergence and persistence of hierarchical classes—as well as their reproduction and crises? Many such stories already exist: Federici’s reading of the transition from feudalism to capitalism not as anti-feudal progress led by capitalists but as a capitalist crackdown on the anti-feudal struggles of women peasants40; Boehm’s accounts of hierarchy-leveling tactics like ridicule and disobedience among hunter-forager communities41; Graeber and Wengrow’s analysis of political experiments with seasonally varying hierarchies in places like Palaeolithic Europe and Neolithic Çatalhöyük.42 In these alternative grand narratives, the success of emancipatory struggles is not marked by the victory of one class over another, but by the defeat of class society itself.

Today, these struggles have become naturalcultural in scale, as atoms, molecules, objects, and organisms increasingly join humans in revolting against class society. Accumulating carbon atoms in the atmosphere, methane molecule releases from the ocean, or escalating species extinction events could all overturn the global political economy in its current form. These “revolts” may not be intentional in the conventional sense of human political struggles, but they nonetheless substantially contribute to the intensifying crisis of class society. Production overlaps with reproduction. Means of reproduction underpin means of production. This historical development underlies the click-baiting language of the day: renewables, sustainability, circular economy, right to repair.

Repair, as an emerging force for reproducing class society (which coexists with older such forces like spatial and outer-spatial fixes), takes on two forms: authorized and unauthorized. Authorized repair aims to fix the damage of class society to keep it in place. Renewable energies purport to resolve the fossil fuel crisis to sustain energy-intensive class hierarchies. Offset projects absorb atmospheric carbon to clear the way for the future emissions of the “Carbon Liberation Front.”43 Meditation apps and private therapies medicalize naturalcultural grief in the language of personal disorders to stabilize class society’s desiring-production. Authorized repair is organized by and for the ruling classes.

Unauthorized repair seeks to fix the damage of concrete naturecultures with as little involvement of the ruling classes as possible. Huaqiangbei repairers mend unwanted phones imported from the overdeveloped world with locally developed tools and tricks to sustain their livelihoods. US farmers hack and repair their tractors to keep up with harvests when the authorized mechanic is always too little too late.44 Taking repair in a more general sense, one might also think of transformative-justice intervention circles.45 Or harm reduction clinics.46 Or the Chinese Big Tech hackers’ organization of an “Intensive Care Unit” to treat the life-threatening 996 work schedule imposed by their vectoral employers.47 All of these might be considered experiments with radical emancipatory repairs based on the imagination of alternative relations of reproduction. Unauthorized repair aims to fix not just the problems caused by class society, but the problem that is class society.

Politics

A politics of repair is a healing politics. This healing politics doesn’t seek to overthrow, reform, or return to the old; nor does it still believe in a miraculous leap into the radically untethered new. It reassembles, reinvents, and remakes. It re-pairs. Healing politics discloses the path for expressive politics to stage its escape from the actual into the virtual, from what the world is into what it can become.48

Consider this story from Xiaole, the repair stall technician who amicably promotes Huaqiangbei’s repair power. “Look at this, an iPhone SE with dual SIM! Have you ever seen such a thing?” Before his special customization, the original phone—assembled by himself with secondhand, thirdhand, or multi-hand components sourced from neighbor stalls and fellow repairers—was just like any other iPhone SE with a single SIM card tray. After a while, the handset’s SIM connection failed and Xiaole opened it up to make some repairs. “When I was fixing it, it suddenly occurred to me: Why don’t I just replace the broken part with a dual SIM reader and reroute the circuits!!”49 In such moments of breakdown, the virtual sprouts from the cracks of the actual. Here the virtual refers not to the immaterial or the digital. Rather, the virtual is, as Wark says, “the inexhaustible domain of what is real but not actual, what is not but which may become,” “the possibility of new worlds, beyond necessity,” and “the inexhaustible multiplicity of the future.”50

Wark: “To produce is to repeat; to hack, to differentiate.”51 To repair is to remix the repetitive into the different. Perhaps the idealization of subversive hacks and genius hackers—still fettered to originality fetishization, ingenuity myths, and knowledge hierarchies—can easily take on an aristocratic form that risks a false separation between normal commoners and the supposedly truly expressive agents of hacker history. Hopefully, repair offers a more accessible, vulgar path of escape. Breakdown is the humble, ordinary moment of revelation, when a surplus of virtual possibilities—for repair and remake—disclose themselves to everyone, regardless of technical skill or innovative genius. Repair is the feasible practice for common folks to reassemble the actual into the virtual.

If Xiaole’s dual-SIM repair seems unrelatable as an example, think of the times when we casually fix a broken eyeglasses arm with superglue, or wrap the exposed wiring of an old charging cable with tape, or patch a pair of worn-out jeans.52 A repaired item may look and work just as the old one. This seeming restoration of the old belies its underlying transformation into the not-so-new: something that has been repaired, that can be repaired, and that will be repaired, over and over again—perhaps into something that’s more obviously different-looking, perhaps not. Alice Walker: “Healing begins where the wound was made.”53

Struggle

If expressive politics is the struggle for an alternative practice of everyday life, the struggle of healing politics is a guerrilla game of parasitism and complicity with the ruling classes. In an age where it is said that there is no alternative, and where it is made to be so, the struggle of parasitism takes on greater relevance than the struggle for alternatives, just as used brand-name phones became more prized after the decline of the more widely mediatized and theorized shanzhai handsets (山寨机).

The Huaqiangbei second-hand phone markets have not always sold second-hand phones. Before there was a demand for used handsets from famous brands, these malls were all about shanzhai: cheaper, usually unbranded imitations (or enhancements, depending on one’s point of view) of foreign-brand handsets by local small businesses in China. Popular stories about shanzhai usually go one of three ways. For leftist observers, shanzhai is the rebellious subversion, parody, mutation, or destabilization of the original intellectual property and its corresponding power structures.54 For startup entrepreneurs, shanzhai is the perfect business-school case study to inspire their next big idea of something slightly different from the original IP in order to register a new IP.55 For original IP holders, shanzhai is both an outrageous legal infringement and a geopolitical threat that needs to be brought into line with moral condemnation, legal actions, or a trade war.56

A Huaqiangbei independent repairer at work, 2024. Photo: Yifan Wang.

But few account for what happened to shanzhai after its heyday around 2005. In late 2007, Chinese authorities scrapped their old cell phone industry regulatory scheme based on production licensing and began adopting a more sophisticated model that controls handsets through IMEI registration and carrier network connection. Before 2007, a company’s eligibility to manufacture mobile phones had been regulated via its possession of a physical production permit. Now, enforcement operates through state-controlled vectoral data about individual handset models, serial numbers, network types, and so on. In other words, while smaller producers had previously been able to pool resources to obtain one manufacturing license for collective use, the new regulatory paradigm based on sophisticated, digitally recorded information squeezes such legal gray zones for micro-businesses. A manufacturing regime is updated into a vectoral one. Control over physical devices is achieved through informational apparatuses. If media theorists once found it pertinent to stress the material substrate of code, software, and information, a kind of reverse phenomenon begs for analytical and political attention now: physical hardware and its functionalities—even the utmost mechanical ones—are increasingly managed by software-based vectoral systems on the cloud. (Much of our stuff now won’t work without a corresponding app, an operating system, or a digital subscription. Think electric cars, light bulbs, printer cartridges, and television sets.)57

Meanwhile, also since 2007, vectoral giants like Apple and Google have begun making their way into the cell phone industry, setting off a new business strategy of smart-izing handsets with complex operating systems and customizable applications. The competitive success of a phone maker increasingly depended on its access to vectoral expertise like software engineering and user-interface development. The political-economic viability of the shanzhai model—one based on shanzhai producers’ advantages in the physical manufacturing of feature phones—gave way to a new era of vectoral smartphones.

Amid this double expansion of China’s unique blend of state and private vectoral powers, entry barriers are raised, smaller players are kicked out, and a market of dazzlingly diverse shanzhai phones consolidates into a handful of domestic firms that fuel sales with consumerist nationalism.58 Shanzhai, once at the center of attention for Beijing officials and international observers alike, has long receded from the center stage of Chinese social media and its market of ideas. In the market of things, shanzhai products have taken on a new form that’s hardly recognizable as shanzhai. If you want to get a cheap phone in China these days, you’d go for an Oppo or Xiaomi, the shanzhai brands that have ended shanzhai.

In place of shanzhai phones and their hackers, second-hand devices and their unauthorized repairers have entered the stage. For shanzhai hackers, the question is one of old or new, imitation or innovation, repetition or difference, joining or quitting the game. For unauthorized repairers, the question is a bit more complicated. The repairers fix proprietary products by breaking proprietary restrictions. They violate IP rules in order to benefit from IP rules (after all, a refurbished iPhone is only profitable because it’s an iPhone). They hate commodified information that fetters their healing powers. They love commodified information as the brand-name magic that commands premium repair prices. They restore physical sameness yet produce political-economic difference. They reproduce a sameness that rejects privatized difference, just as they create a difference in the form of knockoff sameness.

Repairers are neither misbehaving rulebreakers, nor unorthodox winners, nor maverick dropouts. They are both the parasite and the host of the global smartphone system. Every time a new iPhone model comes out, a slew of tailor-made parts, screws, tools, trader circles, and chat groups begin to form around it, parasitizing off of the new launch’s carefully curated vectoral media hype and rerouting it into Huaqiangbei’s own circuit of second-hand flows of supply, demand, capital, and vectors. At the same time, it is these very same communities of workers, technicians, tools, objects, and factories that make the pervasiveness of iPhones possible to begin with. “A single iPhone model could feed a whole bunch of us,” a Huaqiangbei repairer once told us. It is also the whole bunch of us that feed corporations like Apple.

When alternative, off-the-grid mountain strongholds—shanzhai’s literal meaning—are ever more intensely controlled or commodified by the spreading tentacles of vectoral powers, unauthorized repairers turn the enemies’ weapons back at them. The struggle of healing politics is parasitical, just as the rule of vectoral power is parasitical. The key concern for parasites is not repetition or difference, but the downstream. Michel Serres: “The law of the relation is to place oneself below another, so that the chestnuts fall unimpeded. Below, deeper, further down in the well, or further downstream. The one downstream is the one who wins.”59

Class

“Farmers, workers and hackers confront in its different aspects the same struggle to free information from property, and from the vectoralist class,” writes Wark. “The most challenging hack for our time is to express this common experience of the world.”60 Repairers help to identify a uniquely advantageous strategic position for approaching this challenging hack. Rarely cut into any deal with the ruling classes—be it the historic compromise in the overdeveloped world over surpluses from the underdeveloped world, or nationalistic promises defined along state borders, or the unevenly distributed economic growth benefits from vectoralists-dominated globalization—repairers have little vested interest in any existing arrangement. The repairer is an outcast everywhere, a scavenger of exported wastes, an inconvenient presence that reminds one too much of decay, ruin, and wound in the storm of what we call progress.61

Accompanied by the repairer, one could therefore take leave for a time of both the noisy sphere of circulation and the hidden abode of production, and instead venture into the all-too-easily forgotten domain of maintenance.62 Removed from the marketplace and the factory floor, a broken thing—its dazzling casings and mystifying components taken apart—calls for collective action from all productive classes. The repairer cuts through the dominant division of labor along class lines, and destabilizes the consequent mismatch of politics among farmers, workers, and hackers. Here, opportunities abound for overlooked, understudied tactics and strategies of alliance-making that could broaden all productive classes’ imagination of “the most challenging hack.”

In Huaqiangbei, it’s hard to say whether someone is primarily a farmer, a worker, a hacker, or a repairer. A-Ling, whom we met above, alternates between a farm boy and a self-employed repairer. During harvest seasons or the Lunar New Year, he goes back home to a rice-farming village in central China to help in the fields. In other months, he is stationed in his Huaqiangbei stall, fixing one phone after another. His mechanical tools are made by factory workers in suburban Shenzhen, and his digital tools (such as interactive circuit-board schematics and troubleshooting software) are developed by programming hackers sitting in nearby office buildings.

These same workers and hackers, and their capitalist employers, probably also take manufacturing orders from overseas vectoralists. (A-Ling himself, like many other Huaqiangbei repairers, spent years on factory floors as an assembly-line worker before becoming a repairer.) Meanwhile, every week or so, recyclers come to buy back completely unrepairable parts from technicians like A-Ling at around fifty dollars a kilogram. These not-so-wasted electronics are then shipped to regional villages to be acid washed, burned down, or taken apart by farmer families excluded from the state’s urban-centric welfare system and struggling to sustain a decent living solely from their nonindustrial small-scale farming. The scavenged silver and gold, recouped from those beyond-repair electronics, then return as investment metals and their derivatives, circulating back into the global flows of commodities, capital, and information.

Around repair activities, a hodgepodge of people and things, classes and positionalities, come together. Importantly, such cooperation across productive and reproductive classes allows Huaqiangbei repairers to develop a unique approach to pushing against the repair blockade of vectoralist corporations. Unlike many right-to-repair movement strategies in the overdeveloped world that primarily rely on legislative initiatives and media advocacy, Huaqiangbei repairers are able to adopt a form of anarchist direct-action repair that cuts out any representational politics.63 Thanks to close ties to electronics workers, engineers, programmers, recyclers, and their respective knowledge and tools, Huaqiangbei repairers can fix as if they are already free from encryption blocks and corporate sabotage.

Outside of Huaqiangbei, across the overdeveloped and underdeveloped worlds, electronics repairers are forging similarly imaginative, autonomous, makeshift alliances that traverse class and state borders. Repairers in Dhaka learn new techniques from Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and online GSM forums.64 Indian repair-tool sellers advertise Chinese-branded equipment on YouTube.65 French technicians seek MacBook repair tricks from Shenzhen.66 Beyond electronics, repairers—in the broader sense of the word—are also coming together across boundaries. In abolitionist pods.67 In healing justice spaces.68 In holograms of care.69 In Indigenous land rematriation sites.70 And, perhaps with more worrisome implications, in carbon-offset solar power plants.

One could think of all these as examples of a new class antagonism in the making: a repairer class and what one could call an offsetter class. Repairers do the patient, messy work of fixing naturecultures broken by landlords, capitalists, and vectoralists. Offseters privatize and assetize the results of the repairers’ labor, turning natureculture justice into a consumer choice or investment opportunity. This new class antagonism merges itself with existing class relations. And struggles against this new class antagonism merge with struggles against existing class relations.71

But on the other hand, we could propose another thought experiment: What if this is not about class struggle anymore? Maybe the category of class has lost much of its strategic and political potency in contemporary mobilization. After all, a key part of the ruling classes’ efforts to break down labor movements has been to weaken worker power by mass-creating nonunion administrative jobs, outsourcing to hiring agencies, contracting temporary workers, or turning taxi drivers into Uber users.72 Both the ruling and productive classes have multiplied and diversified into numerous intersections of simultaneous comrades, allies, difficult friends, and friendly-looking enemies. adrienne maree brown: “We must make our current enemy our future forgiven neighbor.”73

It’s perhaps time to design new weight-bearing metaphors for new actions. The right to the city, multitude entrepreneurship, and temporary autonomous zones are all useful examples.74 Repair could be another. Given the inevitably heterogeneous range of human and nonhuman actors involved in any repair activity, the timespace of repair is one marked by messy entanglements, unruly objects, improvised connections, and shapeshifting tactics.75 Steven Jackson: “All working technologies are alike. All broken technologies are broken in their own way.”76 When positional warfare based on a singular class location won’t cut it anymore, the mobile tactics of summit blockers, park occupiers, pipeline saboteurs, and guerrilla repairers seem more fitting.77

Recall repair influencer A-Bin. In another one of his widely viewed videos, titled “the point of repair,” A-Bin pronounces: “The point of repair is that if you can repair it, you don’t want to upgrade it.”78 Another world is possible, but maybe that other world is not so much an upgraded one as a repaired one, healed from the naturalcultural traumas inflicted by hierarchical classes. Alexis Pauline Gumbs: “What if abolition isn’t a shattering thing, not a crashing thing, not a wrecking ball event? What if abolition is something that sprouts out of the wet places in our eyes, the broken places in our skin, the waiting places in our palms, the tremble holding in my mouth when I turn to you?”79 Revolutionaries have hitherto sought to change—to break—the world in various ways. The point, now more than ever, is to repair it.

This refers to the practice of disabling third-party hardware components through code-based encryption software and firmware. An example can be found here →.

See Dai Jinhua and Jingyuan Zhang. “Invisible Writing: The Politics of Chinese Mass Culture in the 1990s,” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, vol. 11, no. 1 (1999); Nathan Sperber, “Party and State in China,” New Left Review, no. 142 (July 2023); and Zhiming Long, et al., “On the Nature of the Chinese Economic System,” Monthly Review, October 1, 2018 →.

Mary Ann O’Donnell, “What Kind of Public Space Is the City of Shenzhen?” The Emerging Public Realm of the Greater Bay Area, ed. Miodrag Mitrašinović and Timothy Jachna (Routledge, 2021), 90.

For an examination of Jodi’s game modification works, see →. For reporting on shanzhai handphones, see David Barboza, “In China, Knockoff Cellphones Are a Hit,” New York Times, April 27, 2009 →. On Deng Xiaoping–style grassroots entrepreneurship, see Learning from Shenzhen: China’s Post-Mao Experiment from Special Zone to Model City, ed. Mary Ann O’Donnell et al. (University of Chicago Press, 2017).

For theorizations on “people’s war,” see Wang Hui, China’s Twentieth Century: Revolution, Retreat and the Road to Equality (Verso Books, 2016), 110–15. For more on digital rights management, see Sascha D. Meinrath et al., “Digital Feudalism: Enclosures and Erasures from Digital Rights Management to the Digital Divide,” Advances in Computers, vol. 81, ed. Marvin V. Zelkowitz (Elsevier, 2011), 237–40.

China-based repairers don’t typically face the same difficulties since most of their tools and parts are locally made, often in factories miles from Huaqiangbei.

Early precedents of the ecosystem enclosure strategy can be found in the US auto industry, which helped drive America’s rise as a global power in the twentieth-century just as the consumer electronics industry underpins China’s growth in this century. Ford was among the first to standardize repair services, while General Motors pioneered early experiments on mixing planned obsolescence with brand image advertising, hinting at the emergence of vectoral power in its nascent form. They understood that sales depended on an ecosystem of after-sales. These new business practices emerged around the early 1900s, a time of an intensifying crisis for Adam Smith–style capitalism. That crisis gave rise to various repair attempts, including Keynesian economics, the Walter Lippmann Colloquium, a Cold War, and eventually vectoralism. See Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe, The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective (Harvard University Press, 2015).

For discussions on Biden and the Green New Deal (GND), see Daniel Goulden, “We Need a Real Green Jobs Program to Fight Climate Change,” Jacobin, October 4, 2023; and Alyssa Battistoni and Geoff Mann, “Climate Bidenomics,” New Left Review, no. 143 (2023). For an activist GND vision, see →.

Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore, A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet (University of California Press, 2017). See also Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (Verso Books, 2011).

Rob Aitken, “Depletion Work: Climate Change and the Mediation of Stranded Assets,” Socio-Economic Review 21, no. 1 (2023): 267–70.

Benjamin H. Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (MIT Press, 2016).

Wark, Capital Is Dead: Is This Something Worse? (Verso Books, 2019), 48.

See for example Donald MacKenzie, “Making Things the Same: Gases, Emission Rights and the Politics of Carbon Markets,” Accounting, Organizations and Society 34, no. 3–4 (2009); Gavin Bridge et al., “Pluralizing and Problematizing Carbon Finance,” Progress in Human Geography 44, no. 4 (2020); Kean Birch and Fabian Muniesa. Assetization: Turning Things into Assets in Technoscientific Capitalism (MIT Press, 2020). See also →.

See →.

Wark, Capital Is Dead, 123.

Agustín Fuentes, “Naturalcultural Encounters in Bali: Monkeys, Temples, Tourists, and Ethnoprimatology,” Cultural Anthropology 25, no. 4 (2010): 600–1; Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness (Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003), 1–10.

McKenzie Wark, Molecular Red: Theory for the Anthropocene (Verso Books, 2016), 10–20. See also →.

Eyal Weizman and Fazal Sheikh, The Conflict Shoreline: Colonization as Climate Change in the Negev Desert (Steidl, 2015), 12.

Melissa Checker, “Wiped Out by the ‘Greenwave’: Environmental Gentrification and the Paradoxical Politics of Urban Sustainability,” City & Society 23, no. 2 (2011): 210–13.

Robert Poirier and David Ostergren, “Evicting People from Nature: Indigenous Land Rights and National Parks in Australia, Russia, and the United States,” Natural Resources Journal 42, no. 2 (2002): 331–38.

Mitchell, Carbon Democracy, 180–81.

Lily Zhao, “Workers Die in Extreme Heat During China’s Summer,” World Socialist Website, October 17, 2022 →.

Robert Wade and Geraint Ellis, “Reclaiming the Windy Commons: Land Ownership, Wind Rights, and the Assetization of Renewable Resources,” Energies 15, no. 10 (2022).

Blaine Friedlander, “Climate Change Has Cost 7 Years of Ag Productivity Growth,” Cornell Chronicle, April 1, 2021 →.

See →.

Fariha Roisin, Who Is Wellness For?: An Examination of Wellness Culture and Who It Leaves Behind (Harper Wave, 2022).

McKenzie Wark, A Hacker Manifesto (Harvard University Press, 2004), thesis 153.

Reece Walters and Maria Angeles Fuentes Loureiro, “Waste Crime and the Global Transference of Hazardous Substances: A Southern Green Perspective,” Critical Criminology 28, no. 3 (2020); Emily Brownell, “Negotiating the New Economic Order of Waste,” Environmental History 16, no. 2 (2011): 262–64.

Marx, Capital, vol. I (Penguin UK, 2004), 711.

Fraser, Cannibal Capitalism: How Our System Is Devouring Democracy, Care, and the Planet—and What We Can Do About It (Verso Books, 2023), 9.

See →.

Louis Althusser, On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Verso, 2014).

Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression, ed. Tithi Bhattacharya and Liselotte Vogel (Pluto Press, 2017).

Pierre Bourdieu and Jean-Claude Passeron, Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, trans. Richard Nice (Sage Publications, 2000).

Paul A. Baran and Paul M. Sweezy, Monopoly Capital: An Essay on the American Economic and Social Order (Monthly Review Press, 1966); Rosa Luxemburg, The Accumulation of Capital: An Anti-critique. Imperialism and the Accumulation of Capital (Monthly Review Press, 1972).

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Commonwealth (Belknap Press, 2011), 275.

The most iconic of such narratives is probably Marx’s take on how “the weapons with which the bourgeoisie felled feudalism to the ground are now turned against the bourgeoisie itself” by the proletarians. Then there’s also Adam Smith’s epic story of the four stages of human history, or futurist Alvin Toffler’s account of the three waves. See Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848) →; Smith, The Wealth of Nations (Penguin, 1999); and Toffler, The Third Wave (Bantam Books, 1980).

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (Autonomedia, 2014).

Christopher Boehm, Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behaviour (Harvard University Press, 1999).

David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021).

Wark, Molecular Red, 1–6.

Jason Koebler, “Why American Farmers Are Hacking Their Tractors With Ukrainian Firmware,” Motherboard, March 21, 2017 →.

Revolution Starts at Home: Confronting Partner Abuse in Activist Communities, ed. Ching-In Chen et al. (AK Press, 2016).

See for example Suzanne Morrissey and Olivia Hagmann, “Social Justice, Trauma-Informed Care, and ‘Liberation Acupuncture’: Exploring the Activism of the Peoples Organization of Community Acupuncture,” Anthropology and Activism, ed. Anna J Willow and Kelly A. Yotebieng (Routledge, 2020).

J. S. Tan and Moira Weigel, “Organizing in (and Against) a New Cold War: The Case of 996.ICU,” in Digital Work in the Planetary Market, ed. Mark Graham and Fabian Ferrari (MIT Press, 2022), 209.

For Wark’s discussions on expressive politics and escape, see Hacker Manifesto, thesis 251, 252, 256, 257, and 273.

Most internet services in China require phone numbers for registration, and many people want more than one SIM card in their phone so they can switch between different digital accounts registered to different phone numbers.

Wark, Hacker Manifesto, thesis 74, 14, and 78.

Wark, Hacker Manifesto, thesis 160.

See →.

Walker, The Way Forward Is with a Broken Heart (Ballantine Books, 2001), 200.

Byung-Chul Han, Shanzhai: Deconstruction in Chinese (MIT Press, 2017).

Silvia M. Lindtner, Prototype Nation: China and the Contested Promise of Innovation (Princeton University Press, 2020), 74–79.

Jyh-An Lee, “Shifting IP Battlegrounds in the US-China Trade War,” Columbia Journal of Law and the Arts 43, no. 2 (2020): 147.

For media-studies discussions on software and hardware, see Friedrich Kittler, “There is no Software,” Stanford Literature Review 9, no 1 (1992); Alexander Galloway, “Language Wants to Be Overlooked: On Software and Ideology,” Journal of Visual Culture 5, no. 3 (2006); and Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, “On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge,” Grey Room, no. 18 (2005). For the digitization of mechanical devices, see for example M. C. Forelle, “The Material Consequences of ‘Chipification’: The Case of Software-Embedded Cars,” Big Data & Society 9, no. 1 (2022): 1–5. See also Cory Doctorow, “Apple Fucked Us on Right to Repair (Again),” Medium, September 23, 2023 →.

Serres, The Parasite (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982), 166.

Wark, Hacker Manifesto, thesis 87.

Walter Benjamin. “On the Concept of History” (1940), trans. Dennis Redmond , marxists.org →. One has to wonder if Benjamin’s Angel of History, with his face turned towards the single catastrophe of the past and his hope for a pause to piece together what has been smashed, must be a repairer.

Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 271–80. We are now accompanied by so many more figures than Marx’s Mr. Moneybags and the labor-power possessor. The hidden spheres in need of scrutiny also stare at us with a far more intricate governmentality of inclusion and exclusion: not just “no admittance except on business,” but also “warranty void if seal is removed.”

See for example April Carter, Direct Action and Democracy Today (Polity, 2005); Uri Gordon, “Anarchism Reloaded,” Journal of Political Ideologies 12, no. 1 (2007): 29–30.

Lara Houston and Steven J. Jackson, “Caring for the ‘Next Billion’ Mobile Handsets: Proprietary Closures and the Work of Repair,” Information Technologies and International Development (special section), no. 13 (2017): 200.

See →.

See →.

Mia Mingus, “Pods and Pod Mapping Worksheet,” Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective, June 2016 →.

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, “A Not-So-Brief Personal History of the Healing Justice Movement, 2010–2016,” Mice Magazine, no. 2 (Fall 2016) →.

Cassie Thornton, The Hologram: Feminist, Peer-to-Peer Health for a Post-Pandemic Future (Pluto Press, 2020).

See →.

“No Climate Justice without Debt Justice,” open letter →.

Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri, Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019).

brown, “Additional Recommendations for Us Right Now From a Future,” Center for Humans and Nature, October 23, 2020 →.

David Harvey, Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution (National Geographic Books, 2019); Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Assembly (Oxford University Press, 2017), 139–43; Hakim Bey, T.A.Z: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism (Autonomedia, 2003).

Such irregularity and uncontrollability of repair spaces in the early 1900s proved to be a major point of friction and a limit to the Fordist model of value extraction. See Stephen L. McIntyre, “The Failure of Fordism: Reform of the Automobile Repair Industry, 1913–1940.” Technology and Culture 41, no. 2 (2000): 269–75.

Steven Jackson, “Rethinking Repair,” in Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, ed Tarleton Gillespie et al. (MIT Press, 2014), 228.

Andreas Malm, How to Blow up a Pipeline: Learning to Fight in a World on Fire (Verso Books, 2021).

See →.

Gumbs, “Freedom Seeds: Growing Abolition in Durham, North Carolina,” in Abolition Now!: Ten Years of Strategy and Struggle Against the Prison Industrial Complex, ed. CR10 Publications Collective (AK Press, 2008), 145.