We Live in Our Screens

Even more pressing than the unfolding permanent crisis just beyond your field of vision is the paid gig before you. And then, how to secure the next gig? Whether waged or casualized workers, we are all precariat now. Our only immunity from job redundancy is visible hyperproductivity. But the quantity of work outstrips the quality as your quickening levels of productivity inhibit your output. It’s all too much.

You seek help. An online search returns a series of “life hacks” to keep you “competitive.” Intuitive interfaces to get ahead, downloads, sign-ups, plug-ins, affirmation apps, tailored solutions. Costing more than money, each demands a pound of data. No time to read the “terms and conditions,” you click “accept.”

What’s the point of all this productivity anyway, when your unremembered dreams and ambitions have been dissolved in the acid of hustle? This cursed game has captured you, pitted you against yourself and others; the order of algorithmic culture has been internalized. Because of these manic logics of work, there’s little by way of collaboration, respect, or good faith between you and those around you. Your relationships are competitive. You know in your bones that you are being scammed by systems and forces beyond reach. We are not hackers, we are the hacked. Not players, but the played. As always, someone’s benefiting here, and it’s not you.

Self care meme.

How did we arrive at this predicament? And how do we get out of it? Can we recall a time, a series of choices, a turning point that might have changed our trajectory to avoid these present conditions? How far back must we look?

Enter A Hacker Manifesto

McKenzie Wark’s A Hacker Manifesto offers tactics that work against the commodification of information by expanding the concept of the hacker beyond its associations with computational technology to encompass a broader range of activities. These include acts that subvert, manipulate, and transform systems of commerce and control across culture, politics, society, and philosophy, and that challenge dominant power structures, data hoarders, and economic logics. For Wark, hacking can be a revolutionary act, an activism of the “digital proletariat” that aims to liberate information from the clutches of the ruling class. Beyond a call to arms, her text channels the spirit of the situationists, urging hackers to seize the means of information production and overthrow the commodification of knowledge.1

A Hacker Manifesto is most productively read in conversation with Wark’s Gamer Theory, which more explicitly maps the coordinates of the present we now occupy. There, Wark articulates the “gamespace,” by which she means a landscape in which the zero-sum calculation of everything mutates the proletariat into perpetual players, or at least “playborers,” to borrow Julian Kücklich’s terminology.2 This logic of “gamification” cojoins culture and entertainment within an economic calculus,3 and brings to life the abject horror of a high-stakes game that one is forced to play, an idea rehearsed across contemporary fiction franchises like the Hunger Games, Squid Game, and Saw. Because of this gamification of social relations, argues Wark, video games simulate the truths at play in the lie of reality. They present fair and functioning systems that can be conquered by perfecting one’s play, an integrity that the gamespace of everyday life cannot deliver.

Both books build upon a virtual geography whose contours and vectors are mapped in Wark’s earlier writing.4 Each charts a global media space in which the chaotic crises of technology and political economy are deeply intertwined. Where A Hacker Manifesto invites and articulates a utopian revolutionary class (the hacker), Gamer Theory offers a more pessimistic reading, one that has increasingly become manifest in predicting how social, political, and economic systems would adopt the language and logic of games. The productive question arising at the overlap of these two books is: How can the principles in the more utopian A Hacker Manifesto be applied to the dystopian gamespace of the present moment?

Addressing this idea in the present and future requires mapping the genealogy of both works. Published following Wark’s emigration to the United States in 2000, each book expands ideas, vocabularies, and networks from the 1990s but extends this ambition into speculative futures. A Hacker Manifesto developed out of Wark’s engagement with the digital media avant-garde at the turn of the millennium, particularly in contexts such as the online theory forum Nettime.5 Gamer Theory instead emerges from the vibrancy of New York’s experimental and critical game milieu at Eyebeam and the Re:Play conference.6 Amidst these international networks of artists and collectives, critical understandings of the digital present began to emerge.

By the 1990s, for a growing number of people the rising tide of digital culture had come into full view. Desktop computers and video-game consoles had established themselves in homes; mobile phones were increasingly commonplace; software and programming generated new (internet) literacies, while games and interactivity solidified as new logics in the media landscape. Emerging in tandem with a then pervasive techno-optimism, these digital concepts and devices, the practices they enabled, and the transformations they heralded called for critical theorization.

Tackling any assumed male gendering of the digital, British cyber-feminist scholar Sadie Plant mapped a rich lineage of women programmers from Ada Lovelace to Grace Hopper.7 At the University of Warwick, Plant cofounded the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU) with Mark Fisher and Nick Land. Blending cyberpunk surrealism with critical theory and Gothic Horror, the CCRU took on radical and occultist dimensions. In their search for alternatives to the digital capitalism to come, “accelerationism” would play a key role—a term that has since been taken up to suit fringe and reactionary narratives rather than these earlier uses.8

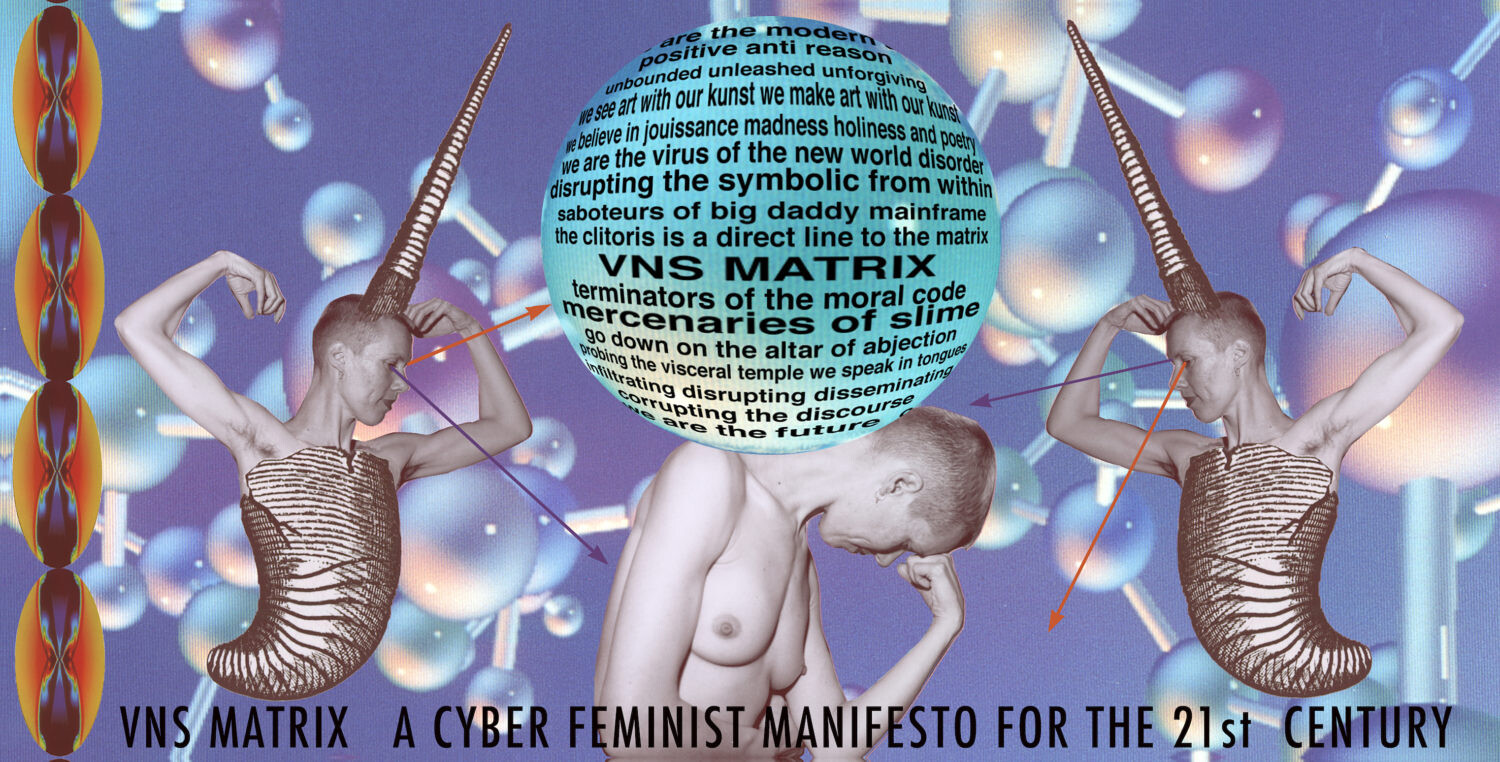

Half a planet away in Australia, responses to digital futures and gender were far more like the early internet itself: strange, distributed, and diffuse. In a powerful gesture, Australian feminist art group VNS Matrix announced that “the clitoris is a direct line to the matrix” in their “Cyberfeminist Manifesto,” emphasizing the gender-morphing potential of cyberspace. VNS Matrix produced work directly confronting the macho world of video games and positioned themselves more broadly as “saboteurs of big daddy mainframe.”9

Meanwhile groups such as CyberDada made experimental audio-visual incursions in the digital domain. Multimedia artist Francesca da Rimini explored the possibilities of distributed virtual sex. Where the British CCRU was accelerationist, Lovecraftian, and tentacular, the antipodean cyberpunks were more sensual, sexy, and slimy. Each boasts their own expansive contemporaries and hacker legacies.

Deeper Histories

Though Wark first proposed the idea of the “hacker class” in 2000, the hacker as an object of analysis has older beginnings. Wark draws upon and extends ideas from the 1986 “The Hacker’s Manifesto” by Loyd Blankenship, who expounded hacking as an act of breaking information out of prison to broaden collective horizons while transcending selfish desires for exploitation and harm.10 Philosophies of hacktivism appear in yet earlier texts. Theodor Nelson’s Computer Lib/Dream Machines (1974) charts the rise of the hacker ethic within 1960s counterculture.11 Where hippies had sought a radical disconnection from technology and a return to a more “natural” and spiritual reality, hackers embraced technology but sought to reorder its power away from large corporations and toward popular aims.

Computers, Arise! by Theodor Nelson, COMPUTER LIB/DREAM MACHINES, 1976.

The driving philosophy of these early hackers was to challenge the idea of authoritarian gatekeeping. For hackers past and present, openly sharing information was an ethical imperative. Then as now, this notion of the freedom of information would overlap with political movements opposed to authoritarian control, such as socialism, anarchism, and libertarianism.

The activities of these earliest hackers, according to hacker pioneer Richard Stallman, transcended freely shared code and software to include a broad spectrum of activities, “from practical jokes, to exploring the roofs and tunnels of the MIT campus.”12 Examples of such activities include the work of Stewart Brand, who cofounded the New Games Movement and later became the author/editor of The Whole Earth Catalog (1968). Brand and others had extended the sixties spirit of play to counter the domination of capitalism through games and technology, inadvertently presaging gamespace in the process. Histories of hacking run deeper still, with some fruitfully finding a version of the practice in the Protestant Reformation, where proto-hackers worked to unshackle Biblical teachings from the chains of papal supremacy.13

Writing at the turn of the twenty-first century, what Wark brought to this hacker legacy was the urgency of the present. Wark was then and remains now an antenna of the culture around her. During an era of unbridled techno-exuberance, Wark warned that we risked devolving into the darkest mental prisons of the pre-Reformation Church.

A Hacker Manifesto redraws the battle lines of labor, culture, class, and exploitation for the digital age. Drawing on a network of theoretical influences from Guy Debord to Gilles Deleuze, the situationists to Karl Marx, the book outlines an emerging class conflict between, on one side, makers, researchers, authors, and artists, and on the other those who commodify information and monopolize what the hacker produces, namely information. Crucially, Wark’s concept of hackers does not label them as digital dissidents, but rather as a creative class. Hacks don’t simply disrupt existing closed systems; they imagine curious and inventive new approaches.

In this way, hacking is shown to be a kind of alchemy: a transformation of the material and immaterial into something new. Where the ruling class (the “vectoralist class” in Wark’s words) seeks to commodify this newness, hackers resist the control of information, challenge commodified existence, disrupt the smooth functioning of capitalism, and open new possibilities for emancipation. Operating at the limits of the legal, the hacker thinks beyond legislation to explore new modes of creativity and communal exchange. Wark’s manifesto captures both the tactics and the romance of this identity. The hacker cuts a nostalgic figure, gracefully rappelling across the edifice of power and control, displaying a deft subversiveness and a collectivist spirit that is sorely missing today.

But these ideas have fallen somewhat flat in the two decades that have followed. To the contemporary reader, A Hacker Manifesto is dated by an over-occupation with patents, intellectual property, and copyrights, concepts that pervaded that era of file sharing and pirating but that seem distant and quaint today. Perhaps more importantly, key examples of the hacker class the book celebrates have, in the years since its publication, been criminalized. Snowden, Swartz, Manning, and Assange are nothing if not hackers of the first degree. Furthermore, the intervening years have seen a pronounced shift in digital culture. Its communities have been vacuumed up into social media services, its commons commodified by Big Tech, its activist potential transformed into an economic terrain. So-called “digital disruption” has led to new concentrations of wealth, theorized as mutant modes of capitalism, be it platform, surveillance, or algorithmic.

As Wark has described more recently, however, these emergent modes of extraction and accumulation are not capitalist permutations, but instead evidence of capitalism’s decline. In its place, new and worse forms of predation and extraction are arising, yet we lack the vocabulary to name them. Arguably, here is Wark’s most significant and original contribution in A Hacker Manifesto: the articulation of vectoralism as a new ruling class along cyber-Marxist lines.

Vectoralism

If the hacker class creates new possibilities for production and knowledge sharing, the vectoralist class appropriates and commoditizes not just the mode of the hack itself, but any value it produces. Unlike previous overlords, the vectoralist is little interested in the ownership of material assets, instead seeking control of the logistics through which they are managed. Their power rests not in assembly lines but in the flow of information.

Examples of this dynamic abound in the most banal everyday products. Smartphones and game consoles (increasingly the same thing) are not made in factories owned by Apple, Sony, or Nintendo. Their design, manufacture, and assembly are discreet processes that are organized where wages are cheapest. If “globalism,” as Wark writes, can become “the transcendent power of the vectoralist class over the world,” then the vectoralist dynamic connects resources, labor, and markets in a planetary-scale vectoral infrastructure.14

Certainly, the industrial and financial capitalist and the vectoralist share much in common, each creating new value chains and amplifying inequality, oppression, and exploitation in the process. But where the capitalist exploits nature, labor, and culture to generate surplus value, the vectoralist exploits information and logistics to strengthen existing apparatuses of domination. Where capitalism found ways to commodify leisure time as well as work time, the vectoralist transformed work into play—and play into work. The impact of vectoralist thinking on our present gamified relations requires urgent analysis.

Enter Gamer Theory

Gamer Theory reboots the framework Wark laid out in A Hacker Manifesto to discuss the aesthetic form that, she argues, best fits the age of vectoralism: that of the video game. Born online, Gamer Theory initially took the form of an networked conversation combining Wark’s interest in experimental writing techniques, recalling 1990s forum dialogue.15 The online book enabled hundreds of gamers, theorists, and others to offer critique, arguments, and feedback on the manuscript, which would later appear in print format with the online commentary included. The impression is of a singular combination of critical theory and popular culture engaged in dialogue.

Unfolding across nine chapters, Gamer Theory guides the reader through the vectoralist logic, showing how subjects are initiated into systems of control. Wark reveals how media-soaked reality does not merely resemble a game but is increasingly governed by the same military-entertainment complex that manufactures and distributes computer games globally. The entire political and economic structure of gamespace as experienced through online culture has conditioned the way we understand “freedom.” Our available choices—which are increasingly narrow false binaries between predetermined options—are presented as ludic features that invite our engagement, agency, and play.

Quake 3 Arena advertisement, 1999.

Within gamespace, we are all cast as gamers. Unlike hackers who pry open new worlds of opportunity, gamers play in the world but are in turn played by the vectoralist class that controls it. Where the hacker produces, the gamer reproduces. Where the hacker exceeds commodification, the gamer is a complicit collaborator in vectoral power. Unlike the hacker, gamers don’t struggle against high-ranking class enemies, but instead compete against each other for ranking. Being loses its qualitative dimension. Gamers are each quantified identities, always keeping score. No amount of points scored will allow one to rise out of their class. It’s all a rigged game designed to keep you playing. As Wark writes: “Ever get mad over the obvious fact that the dice are loaded, the deck stacked, the table rigged, and the fix in? Welcome to gamespace.”16

This gamified reality serves in part to distract from visualizing the real levers of power, but there is more at stake with gamespace. Games are machines for harvesting information. During player-game relationships that extend over months and years, every single action, reaction, decision, and communication is recorded across a spectrum of parameters. Contemporary game devices capture vast quantities of data through a variety of embedded sensors: eye tracking, emotion recognition, location, physiological reading, and body-motion tracking. This harvesting process generates currency for the vectoralist. Where browsers were once the reflexive interfaces of market-driven surveillance, today it is your game that knows you better than you do.

It is tempting to hold video games responsible for gamespace. Certainly, while gaming is increasingly the leading theater of distraction and extraction, the logic of the game both predates and extends far beyond video games. Vectorialists took this dynamic and expanded, amplified, and monetized it. What video games provide are algorithmic allegories through which to comprehend gamespace. Through a theorization of video games, we can map gamespace’s contours and the gamer subjectivities within them. Gamer Theory does precisely that. Each chapter explores a video game and what it reveals about our ludic world. But a critical difference separates the logic of video games from the reality of our shared gamespace. While video games tend to present functional processes and level playing fields, our lived gamespace is dysfunctional, inequitable, and unfair.

Becoming aware of the existence of gamespace doesn’t mean it goes away. Like any worthwhile philosopher, Wark offers no easy solutions, but instead reveals useful questions. She gestures toward tactics, yet these tactics are themselves ambiguous—literal calls to make our worlds strange and unfamiliar. For example, Gamer Theory proposes the tactic of “trifling,” an idea inherited from The Grasshopper (1978), Bernard Suits’s fable on play. To trifle is not to disengage from the desire to win the game but to playfully explore its workings from within. Whatever tactics we deploy, they must be from within, as there are no exits from gamespace. We may reject its expectations but we cannot reject gamespace itself. As the penultimate paragraph of the book makes clear, “only by going further and further into gamespace might one come out the other side of it, to realize a topology beyond the limiting forms of the game.”17

The only way out of gamerspace is through it.

Playing with Accelerationism

In his analysis of the film series Hunger Games, Mark Fisher focuses on the story’s central presupposition: the inescapable reality that revolution must take place. In the film’s narrative, he writes, “the problems are logistical, not ethical, and the issue is simply how and when revolution can be made to happen, not if it should happen at all.”18 Curiously, in highlighting this “logistical, not ethical” lynchpin to the inevitability of revolution, Fisher evokes the key expertise of the vectoralist class. Must we collaborate with the vectoralist class in their accelerationist games in order to transcend them?

Wark’s insistence that we must playfully reckon with the vectoralist’s terrain of gamespace foreshadows an unavoidable (version of) accelerationism. We must search deeper within gamespace for interpretations of what this might entail. But all machines reach a threshold, eventually exceeding a limit, spinning out of control, and exploding into flames. The philosophy of accelerationism recommends disaster as a requirement to achieve a new stage of human development. Indeed, accelerationists argue that trying to rationally temper the process of techno-capitalism only prolongs the inevitable, in turn exacerbating existing problems along the way. A “just” catastrophe is needed.

There are varied opinions of what such an accelerationism involves, spanning those who advocate for embracing technological progress to those who critique it as cataclysmically final. In Nick Land’s conception, which has devolved into something quite reactionary, accelerationism celebrates a delirious push towards a hyper-technological rapture, with potential for chaotic horror far beyond human control. Far less dystopian or cynical, Mark Fisher delves into the cultural implications of acceleration to rupture established norms and structures. For Wark, accelerationism offers a mode of understanding and navigating the complexities of contemporary post-capitalism and urges the reimagining of politics and society. In all these cases, accelerationism symbolizes both an impending catastrophe and the potential for a transformative hack.

Vault boy from Fallout franchise.

We witness this accelerationist hack in today’s tech culture. Digital innovation no longer responds to any planetary problems or human needs but instead propagates a series of tulip manias: blockchain, Bitcoin, cryptocurrency, NFTs, and now AI. With each, the profane is packaged as profound. The tech start-ups pushing these products arise out of a broken innovation ecosystem entirely dependent upon venture capital for its apparent stellar growth. Vast sums are invested in promises to dominate markets rather than compete on any qualitative basis. Cast as “disruptive,” these vectoralist business models have no interest in service, product, or sustainability. Fortunes are lost and made on how long a confidence trick can sustain itself before selling, going public, or exploding into flames. They are accelerationist games par excellence.

But these controlled explosions within the disaster economy offer no reset; they are simply new business models.19 The revolutionary detonation required is of far greater proportions. Do we have any agency in this ludic trajectory? As we speed-run through this garden of forked paths, where each decision unfolds others, can we steer reality’s avatar? As Wark makes evident, two possible directions lay ahead. The first is to shelter within an imagined past. The second is to accelerate toward an unknown future. To choose neither is to choose the first. If games are a series of decisions, then it is this decisiveness or lack thereof that will determine our fate.

You choose:

Shelter Within an Imagined Past

See also McKenzie Wark, Leaving the Twentieth Century: Situationist Revolutions (Verso, 2024).

Kücklich, “Precarious Playbour: Modders and the Digital Games Industry,” fibreculture 5, no, 1 (2005).

Ingrid Richardson, Hjorth Larissa, and Hugh Davies, Understanding Games and Game Cultures (Sage, 2021).

Wark, Virtual Geography: Living With Global Media Events (Indiana University Press, 1994).

See Readme!: ASCII Culture and the Revenge of Knowledge, ed. Josephine Bosma, et. al. (Autonomedia, 1999).

See Re:Play: Game Design and Game Culture, ed. Eric Zimmerman and Amy Scholder (Peter Lang, 2003).

Plant, Zeros and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture (Harper Collins, 2016).

See #Accelerate; The Accelerationist Reader, ed. Robin MacKay and Armin Avanessian (Urbanomic, 2014).

The Cyberfeminism Index, ed. Mindy Seu (Inventory Press, 2023).

The Mentor (aka Loyd Blankenship), “The Hacker’s Manifesto,” January 8, 1986 →.

Nelson, Computer Lib / Dream Machines (Tempus Books, 1987).

Stallman, “On Hacking,” →.

Wark, A Hacker Manifesto (Harvard University Press, 2004), thesis 250.

This first iteration of Gamer Theory was produced by the Institute for the Future of the Book. Due to the demise of Flash, it no longer functions →.

Wark, Gamer Theory (Harvard University Press, 2007), 25.

Wark, Gamer Theory, 223.

Mark Fisher, “Remember Who the Enemy Is,” k-punk (blog), November 25, 2013 →.

See Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (Macmillan, 2007).