Can it be said that the most efficient political regimes are those that keep the lives of their citizens as close to life and as far from death as possible? Yes. Yet the truth is that in Iran, life is not based on life itself, but on a foundation of death. What I mean is that it is not life that stewards life; rather, it is death and the afterlife that oversee life and all that it contains.

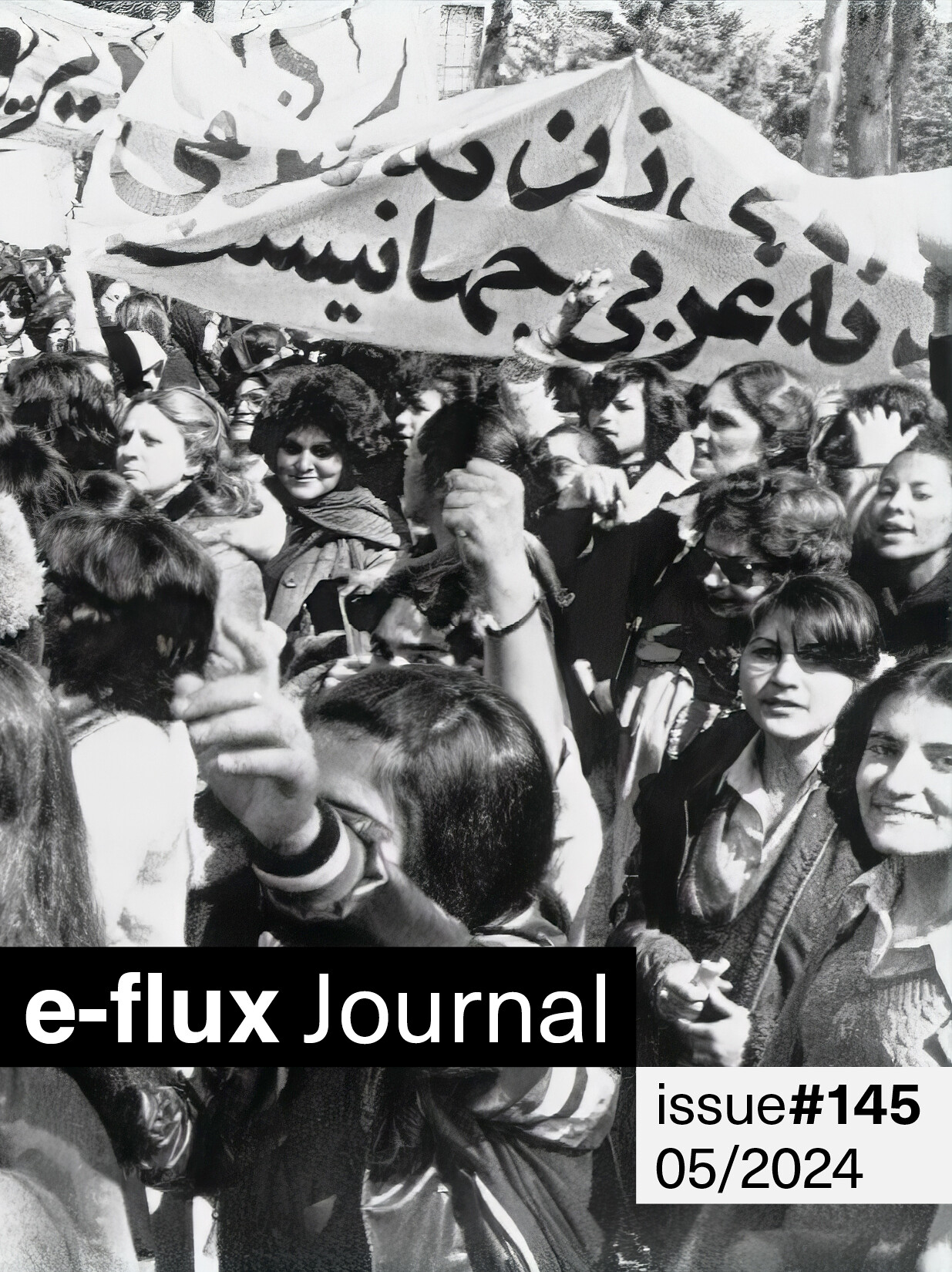

International Women’s Day protests in Tehran, March 1979. The banner reads: “Women’s liberation is not Eastern or Western, but international.” Photo: Richard Tomkins, Associated Press.

This issue of e-flux journal is a collective reflection on the afterlife of the 2022 Jina uprising and the historical and material forces that compelled it. The issue’s authors are all based in Iran and are women activists and writers working across feminist, social, and civil fields. Due to security concerns and the criminalization of dissident voices within Iran, all use pen names to mask their identities. The essays include voices from ethnic and national struggle movements (in Kurdistan and Balochistan), campaigns against the death penalty and for Afghan migrant rights, and movements against the involuntary wearing of the hijab. Against the abstractions of our hyper-mediated time, their writing posits the body as a mode of inscription, as history incorporated, tracing its enforced subjections and emancipatory convulsions through the singular mutations of each body that contributed to the feminist revolution we witnessed. About twenty months since Jina’s point zero, these writings map the movement’s specificity in the genealogy of postrevolutionary insurrections in Iran.

The gap in my father’s memory of 1979 reminds me of the persistent silences in the writings of male leftist during the years after the revolution and in the decades since. With few exceptions, only leftist women have indicted left-wing parties in Iran for their refusal to oppose the mandatory hijab and for the sexism of party members. The powerful have a shorter memory and, with an easy conscience, accept their own silences.

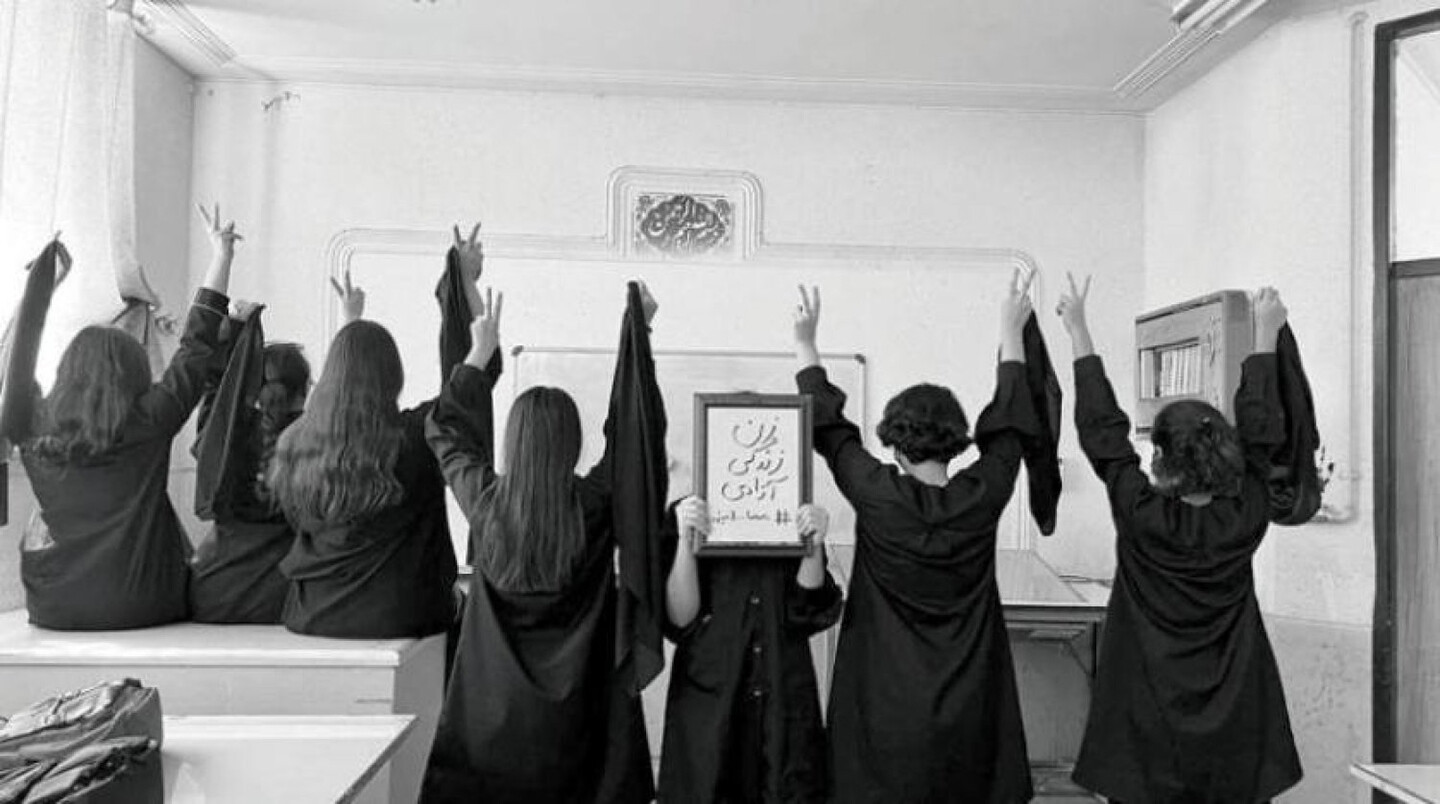

In the last three months, it has felt like a new body has been shedding its skin inside of us. I’m not talking about bravery; nor is this an attempt to describe the body as a site of resistance. My senses are receiving something from the streets that is changing how I understand my body. I have read numerous analyses and interpretations, yet it seems as though the Woman, Life, Freedom movement is a colossal flood that stretches beyond the scope of my vision, gradually eroding my capacity to articulate or grasp it with the familiar words and discourses I have known thus far.

In the early days when the uprising was in its passionate phase (if we consider its current stage as the depressive phase), a strange thing would happen to the protestors. We devotees of the revolution were all dreaming of love and love-making. Dead or unknown lovers came to us in our dreams so we could make love to them. We would wake up in the morning, and by that night, based on our respective time zones, narratives of our dreams would surface. An analyst said to one of the dreamers: “Dreaming of love signals hope.”

The Jina uprising marked a significant turning point, leading to extensive transformations in Iran’s social and political landscape. Unprecedented alliances were formed as marginalized and subaltern groups united to voice their oppressions and participate in the movement, with oppressed Iranians—including women, young people, individuals with disabilities, the elderly, and members of the LGBTQ+ community—taking to the streets with an inclusive interpretation of the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom.” Immigrants from Afghanistan, among the most marginalized groups in Iran, also joined the uprising. Their names are not only on the lists of the arrestees, but among the casualties of the uprising as well.

If during the eight years of the Iran-Iraq War people fought to “defend their motherland,” and if the Green movement was about people “fighting for their right” to determine their future, the Jina uprising seems to have been a more organic and authentic space. This necessary space emerged from desire. The movement conceived of “Woman,” “Life,” and “Freedom”—its key animating ideas—in a way that was before and beyond preconceived notions.

For Borges, Aleph is a place that contains every other place on earth, a place where “all places are—seen from every angle, each standing clear, without any confusion or blending.” An Aleph moment is transformative; it makes us different human beings. In the same vein, we can see the Jina movement as a space-time that distilled other space-times. The Jina movement contains the essences of all the previous protests. In Jina, everyone can see a reflection of the injustices they’ve suffered. Jina’s name lies at the intersection of all class, gender, ethnic, and religious discontent in Iran today.

In a pluralist feminist revolution, the child of the revolution is simply born. There is no need for a midwife. History has done the work. There is no power vacuum for the revolution to fill. The revolution has already found its agents along the way. The time for this revolution is not the future.

This essay was written amidst the flames of anger and blood, and on trembling ground. It is not yet clear to us where the conflict between the military forces of the state/religion/tribe and the oppressed lower strata of society will lead. The outer hard shell of power does not hesitate to do everything it can to maintain the status quo and to suppress the anger of subordinate women and youth. The coming days are important. They will tell of the relentless but disorganized struggle of different assemblages of people who are socially excluded, especially women.