We have magic as entertainment or ritual or perhaps historically as religion. But the magic we know is largely visual with heavy psychological overtones. Our music, in the most extreme interpretation of its complexity, has no purposeful illusionary quality. We expect to recognize what we hear … In the case of the Illusion Models sound will be organized with the sole purpose of creating illusions … In any size space, the Sensors, permanently installed and flawless in their workings, know where the sole auditor is. The information the Sensors are programmed to describe to the sound producing Mechanism tells where the sole auditor is, even if the auditor moves. The sound producing Mechanism makes the auditor think that the physical boundaries of the space in every direction are very far away.

—Robert Ashley1

This note is possibly the most explicit link the composer Robert Ashley ever made between his own work and the work of magic.2 To my knowledge, he never witnessed any of his four Illusion Models (1970) works being performed successfully (perhaps a necessary post-factum add-on joke to his understanding of magic) and in the following years he gradually moved away from technologically driven prestidigitation. In parallel, however, he was developing a different kind of magic that eventually blossomed in his operas, which I discuss here.3 The path to this different kind of magic was paved by his interest in the art of memory, and in particular its hermetic manifestation as worked out by the philosopher Giordano Bruno in the sixteenth century.

The term “art of memory” does not denote a single philosophical doctrine, but rather refers to various systematic attempts at improving memory that begin at least as early as Simonides and continue today perhaps in contemporary schools of “fast learning.” Arguably, there is nothing more to the art of memory than historically evolving sets of mnemotechnics. Yet their praxeological orientation is never devoid of subtexts. It is these subtexts, very often of a magical nature, that were of major, continuing interest for Ashley throughout his work on his interrelated operas, and not merely because of the need to coordinate thousands of minutes of music and dozens of thousands of words. In other words, given the overwhelming amount of information in Ashley’s operas, he might have been interested in the art of memory as a systemizing tool—though the latter does not in the least exhaust the relevance of the art of memory to Ashley’s operas.

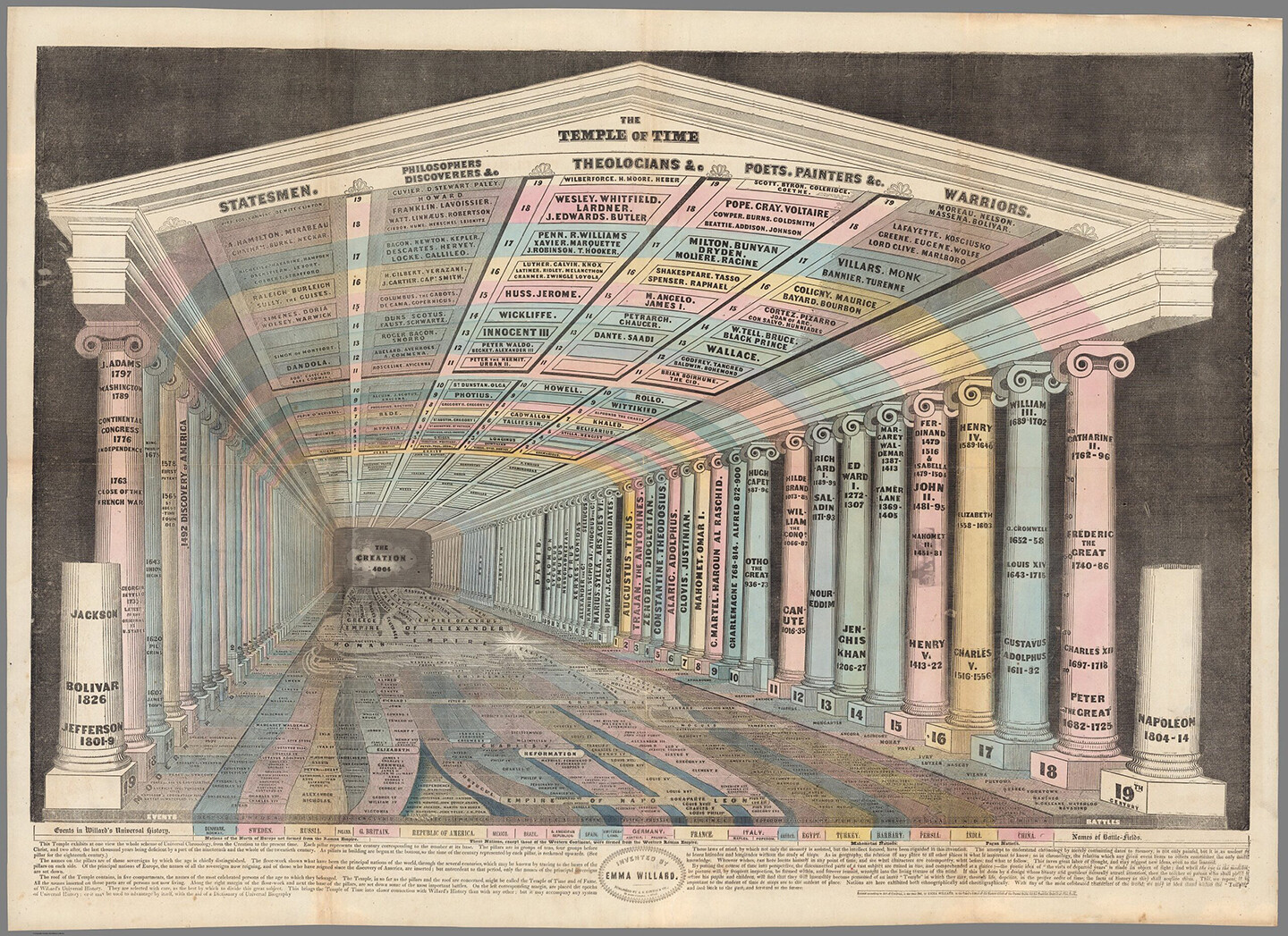

Woodcut from Articuli centum et sexaginta adversus huius tempestatis mathematicos atque philosophos (One hundred and sixty theses against mathematicians and philosophers) by Giordano Bruno, Prague, 1588.

Frances Yates, a key scholar in the history of the art of memory, writes that “artificial memory is established from places and images, the stock definition to be forever repeated down the ages.”4 However, over the centuries, the meaning of terminology changes and thus, as Yates knows as clearly as anyone, the corresponding philosophical details do as well. Sometimes “images” are called “objects,” “bodies,” “adiectis,” or “forms,” while “places” become “loci” or “subiectis” and so on. Still, following Yates, the logic remains the same:

A locus is a place easily grasped by the memory, such as a house, an intercolumnar space, a corner, an arch, or the like. Images are forms, marks or simulacra (formae, notae, simulacra) of what we wish to remember. For instance if we wish to recall the genus of a horse, of a lion, of an eagle, we must place their images on definite loci.5

Ashley adds one more chapter in the historical repetition of this exploration. In fact, his well-known description of opera—“When you put characters in a landscape, that’s an opera”6—is so strikingly similar to Yates’s descriptions, it’s as if he were saying that his operas are themselves examples of an art of memory.

Like any other author of the art of memory, Ashley brings his own jargon and semantics. The key word used here is neither “loci” nor “place”; it is “landscape.” And everything that comes with it seems important: the air, the space, the closeness, the continuity of this background of social life, the scale of it, the planetary aspect, the combination of natural and social shaping, the being-of-the-world that it exhibits. (In other words, it is in the world, in the “landscape,” where magic begins.) Because of all this, “landscape” is perfectly in line with Yates’s functional requirement for an art of memory: like “loci” or “subiecti,” a landscape must be “easily grasped by memory.” Just a few of the settings in Ashley’s operas include: the park, the supermarket, the bank, the bar, the living room, the church, the backyard, condos for sale, lowrider car dealerships, airline ticket counters, the rolling plains of the US Corn Belt, a roadside turnoff somewhere in the southwest, “Most High Desert Reaches.”7 There can be no mistake: Ashely’s landscapes are sites in a specifically American art of memory, one founded on large spaces and movement, if not expansion. The metaphors here rarely consist of ethnographic details, but are rather geographical: coordinates, vectors, cardinal directions, lengths and widths and heights, proportions, astrology, distances of extreme variety. “That’s where you are, seven paces from the toilet / under the golden sky.”8

The album cover of Robert Ashley’s Perfect Lives shows overlapping visual matrices, each of which represents a different act in the opera.

Whatever one puts in the foreground against such a “landscape,” it remains by default part of a larger picture. Even if minor, it is hardly accidental. Quite to the contrary, it is structural; it is always in relation to something else and this relation makes it bigger than it really is. What Ashley brings into the “landscape” he calls “characters.” Not “images,” not “forms,” not “objects,” but “characters.” Again, a meaningful shift of meaning. Have a look at the characters from Ashely’s opera Perfect Lives: Raoul de Noget, “a singer who’s seen better days”;9 his friend Buddy, the “World’s Greatest Piano Player”; D, “also known as ‘The Captain of the Football Team’”; bartender Rodney, “skeptical about boogie woogie” but “philosophical about his wife”; Baby, “manager in the bank,” where also Jennifer, Kate, Eleanor, Linda, and Susie work—“that’s [their] job, mostly [they] help people count their money, [they] like it.”10 And many more. (One more prefiguration: magic goes with the mundane.) Viewed in the context of the art of memory, these characters seem to aspire to something like an American pantheon. It is this exposition that brings to mind Giordano Bruno’s figures on wheels of memory: Neptune, Apollo, or other gods. But while the latter are usually presented with their own attributes (trident, arrow) and animals (horse, python), their American equivalents are embedded in local social relations. And unlike Neptune and Apollo, who never swap their attributes, Ashley characters move around. They circulate in a social milieu, they change landscapes, like everybody does today, they escape, come back, move forward, and to the side.

If Yates is right about the persistent recurrence of the same basic structure of (foreground) objects set against (background) places in all arts of memory, then what makes them different (and thus makes their magic different) is the movement between objects and places, forms and loci, “characters” and “landscapes.” In Cicero and Simonides, movement was hardly there at all. Since their techniques were focused on distributing different objects in various places in a single room, the basic movement was the movement of the eye, maybe the turning of the neck or lifting of the head, at most a walk towards a hidden corner. Bruno, on the other hand, sought to enhance memory using his famous wheels: computational devices containing visual representations of ideas (put into categories) that open the possibility of various connections between them and thus lines of memory. We know little of the way Bruno performed his own magic, except that it was effective (he was offered positions in high courts) and computational. And that the movement was no longer under human control but was an arithmetic of planetary mnemonic powers. This is external memory governed by itself.

Ashley often introduces his characters as Cicero would, except that Roman chambers are replaced by American living rooms centered around fireplaces: “Now, seated at evening, she faces due east, / i.e., placed in space and still aflux in time. / He, on the other hand (that is, her right), / faces pure north, i.e., set in time and / totally adrift in space, huddled at the lamp.”11 We, the auditors, listen, and our ears, step by step, fix the details of the image. There are other ways too that Ashley appeals to memory, much more like Brunonian spinning wheels:

We are on the inside / looking out moving left it takes all day … looking for something interesting / now turn left still on the inside still / looking for something interesting / now turn left the fence is still there keep looking / keep looking for something interesting / now turn left again / still looking still / looking we are looking for food.12

But these mnemonic patterns are overgrown with new ones that reflect the times in which we live today when “more and more … there are strange lights in the sky, and the sense of a past, known through its moment-to-moment-like meshing with the present, is held in doubt.”13

Movements of industrial origins are also integral parts of Ashley’s “landscapes.” In them, voices move around the world in an instant, microwaves heat dinners, bullets break off people’s legs as well as celebrate national holidays, airplanes (even the old type) send us calls from heaven while flying saucers arrive from the future and the cars are everywhere and can do everything, even bring together Three Great Families of the High Desert Region. Yes, all these crazy movements are integral to the content of Ashley’s plots; they are also crucial to how he designs his art of memory called opera, how he makes us hear the plots. (Note: that’s where the magic slowly creeps in.) His art, his techniques are part of the industrial history he pictures.

As an example, take the third act of Perfect Lives, subtitled “The Bank.” We are following a car, “the car that’s full of holes,” heading to Indiana. Gwyn is in the car and she “turns on the auto radio to get a song. Click. / I love-d you like an old time melody / … / I love’d you like a dot dot dot symphony / … / Music bringing back a memory becomes time / stops another treasury I say.”14 Click. Or rather “click” since we, the listeners, actually do the act of “clicking” in our heads. Listening to the opera, we only hear the word “click.” This interplay of clicks (the word and the action) is symptomatic. The moment when Gwyn turns on the radio is introduced by the narrator in a twofold way. First, the fact that the click might be on its way in the plot is announced by the narrating voice that says “turns on the auto radio to get a song.” Then, the moment of turning on the radio, the moment when the click should be heard, is marked or perhaps replaced by the very same voice delivering an onomatopoeic word, and by—with a slight delay—a monochrome gray screen in the video portion of the piece. “Click” thus tells the story while also enacting it. Then, finally, there is a moment of the click in the soundtrack, the click is inaudible, this is the moment when the music changes and hence the “landscape” as well: a jump or shift from a car setting into a song.

This might sound like a trivial development. It is montage. The cut. We—those of us living in the twenty-first century—obviously understand montage quite well, especially if it is performed so clearly and indicated so meticulously like it is here. Montage became a cognitive technique and is one more element of our everyday mnemotechnics. However, there is another element of Ashley’s art of memory that sheds a new light on montage. As he says:

I’m fascinated by the speed in format radio. The announcers speak at an unbelievable tempo. But they make it sound so casual that you think that they’re talking at an ordinary pace. You think that they’re sounding like you. Actually, they’re talking twice as fast as I am. I’ve never heard people talk faster than this, and I know people who really talk fast. Within 12 seconds they give you the news, the weather, everything, plus two or three ads. It’s totally incredible.15

The shift of “landscapes” in “The Bank” is a transition from a “car that’s full of holes” into a song, and can be understood in terms of multiple speeds. There is the speed of voice, pretty much unchanging the whole time. There is the speed of the announcement, the phrase. There is the speed of the onomatopoeia and the slightly delayed speed of the gray image mentioned above. There is also the speed of the click in the soundtrack: this is the click that is omitted, removed, or replaced by the word. Or perhaps, and this is my contention, it is not omitted or removed but rather accelerated. It is so fast that we cannot be on time. We are either too early (announcement), or not sure (onomatopoeia), or too late (already in a new “landscape”). Here, “real fast” means that it did happen, and we know it, and it did happen on the plane of our hearing. But we did not hear the thing. “Real fast” means imperceptible: the click is so fast that it becomes a cut, like in a montage.

Film still from Perfect Lives, directed by John Sanborn, 1984.

This is the industrial heart of Ashley’s art of memory: the way meaning is changed at different speeds. These are mental speeds of our hearing equivalent to airplanes and gunshots. Even faster than these. And then there is the speed of speech. There are times in his operas when the text is delivered in a crazy tempo; there are also times when the same text is delivered in different tempos at the same time; there are different overlaps of time, including the ones when the future precedes the present; there are times when the amount of information seems to change the tempo. And then there is the click becoming the cut in the third part of Perfect Lives. The click is right on the other side; it is just slightly faster than we are and hence it is (for now) physically impossible to hear (for us). (Final thesis: this impossibility of hearing something too fast is an effective element of Ashley’s operas, his audio art of memory and magic.)

Consider what happens in the middle of “The Park” in Perfect Lives. After ten minutes of Ashley’s slow, mantra-like delivery, a shift occurs from a third-person narration (“he sat on the bed, both feet on the floor”) to a first-person narration (“I am sitting on a bench next to myself”). The voice delivery remains the same. The rhythm and the pace of it remain the same. The background music too, it is untouched by the shift. Gradually, by following the props of the imagined scenes, we start to understand that the change in “landscape” must have occurred somewhere there, too. Possibly also a change of “characters”? Only a few lines later, or a dozen seconds into the future, we also learn that “I am not sitting on a bench next to myself.” And soon after that “I imagine there are two men on the bench / The exchange between them will not be seen.”16 It is a bit like “The Bank”; the difference is that in “The Park,” it is unannounced.

Can this be a very simple example of the emergence of a new kind of “character” in Ashley’s opera, i.e., the voice itself? At some point the voice says, “I am completely knowable in every way” and then also “the anger of the words makes me in the dream of myself.” It is not a lyrical subject. It is a “character” that is free enough to shift from embodying other characters of the story to not embodying them and then embodying itself and then not embodying the narrator, whether announced and accentuated or unannounced and unaccentuated. It is grammar acting in speech (but not simply organizing it). Perhaps this ability makes voices “characters” in the “landscape” of music and at the same it makes them “landscapes” for shifting “characters.” Is this not what Ashley meant when he said that his characters are always real (and that real characters can pretend they are not real)?17 What is more real, more “characteristic” in his operas than his own voice (not himself), the voice of Joan La Barbara (not Joan La Barbara herself), the voice of Thomas Buckner (not Thomas Buckner himself)?

And then sometimes, in the warmth of these voices, in their sensual directness, in their straightforward identity—real, bodily—they suddenly perform a cold cut, an unannounced, unmarked shift in characters, which hide behind the voices, a shift that we are always late to perceive, a change we can only grasp in retrospect, after the deed is done, we can only get to it by the work of memory.

The first of three sections titled “Anecdote with Admonition and Song” that we find in Ashley’s opera Atalanta (Acts of God) is about a brain and a throat. “In that most precious part of us, the brain, we are all connected. You heard me. We are all connected. We are connected, each one of us to all of us.” The connections the brain makes are all extremely fast. We are unable to make those connections objects of our perception. They are also inaudible, or faintly audible. But “right beneath the brain there is a thing we call a throat.” The throat vibrates and most of the vibrations, on the other hand, are perfectly audible and easily recognizable. We can also control them. We can make them louder or quieter, higher or lower, or rather, faster or slower. This is called speaking, or singing, and it has an important organic function: “To protect those [brain] connections … we have to talk to slow things down. I mean, the connections would blow up, if we did not have talk to slow things down.”18 We are in the midst of contemporary hermeticism here, and it is a system of speeds.

Robert Ashley, Atalanta, performed at Festival d’Automne in Paris.

The brain is the first axis of Ashley’s art of memory (and perhaps its main “landscape” since it is freed from figurative bonds). This is the axis of the inaudible, the imperceptible. It is faster than the vibrations of the throat. This is modernity. It brings speed. Or rather an extreme variety of speeds. And, if we believe Ashley, the brain is unity, the coordination between the mind and the body through which we become whole. (By the way, is this not the reason why “the exchange between [the two men on the bench] will not be seen”?). Again, the unity cannot be but imperceptible. At least at this point in time, we are unable to experience it. Probably we will be able to experience it in the future. But for now, we can only learn about it. This is big science. And we have technology. But we cannot touch it, not really. We cannot hear it. Yet we have to protect it. No wonder we have problems with concentration, with memory.

The throat is the second axis (and perhaps all Ashley’s “characters” are crammed in here). This is the axis of what we hear. Here come the senses. Vibrations. Even the fastest of senses is incomparable to the speed of the brain. This is the realm of composition. Playing with sounds, overlapping different tempos, juxtaposing extreme speeds, delaying, repeating, variating, accumulating information, diluting it, omitting it (very important), and doing all this with the text too, with grammar; without it, without the text, shifting would be very difficult to recognize, and too arbitrary. It is actually the text, the semantics of it as well as the sound of it, but most of all the grammar of it, that makes it possible to sometimes hear through the audible material, to grasp the underlying speeds, the speeds that are too fast to be composable, the speeds that need to be protected, they can only be modulated.

And, we have learned that we can, whoa, modulate those [brain] connections by differing the sounds the throat makes … And, the parts of the modulation, without a better word than “parts,” are what we call “words.” In other words, the words are ours only, or ours alone. And, that’s why we have to keep on talking.19

This is where the magic is. When the throat and the brain intersect. They rarely do, unless magic is involved. It is like a fifth “Illusion Model,” one for memory (“We expect to recognize what we hear,” remember?). It is like déjà vu—nothing but a difference of speeds of information circling in the brain. It is the rhythm of it, it is the time that opens in the delay of this circling back to itself. This is the way memory works on the edge of memory, when it is not perceived as memory. This is where the magic is, in no magical place. It is where it has always been, right over the edge of our historically determined cognitive skills, just beyond what we are able to grasp. Only very rarely are we able to have access to something beyond our senses in our senses, to hear more than we hear. This is what happens in Ashley operas from time to time. Not often. But if improving memory means anything today, this is it; if there is any future to memory, it is this. The rest can be handled by computers.

Ashley, Outside of Time: Ideas about Music (Musik Texte, 2009), 320.

The text is a development and a reworking of one of the arguments presented in my lengthy analysis of Robert Ashley’s operas commissioned by Antoni Michnik and published in Glissando, no. 44 (2023).

Over the course of his career Ashley composed many operas. A complete list can be found on his website →.

Yates, The Art of Memory (Routledge, 1966), 6.

Art of Memory, 6.

Interview by Thomas B. Holmes, Recordings of Experimental Music 4, no. 2 (1982).

Ashley, Perfect Lives: An Opera (Archer Fields, 1991).

From the libretto for Ashely’s Improvement (Don Leaves Linda) (1985) →.

This is Kyle Gann’s phrase. See Gann, Robert Ashley (University of Illinois Press, 2012), 61.

Ashley, Perfect Lives, 37.

Perfect Lives, 90.

Perfect Lives, 21.

Ashley, Atalanta (Acts of God) (Burning Books, 2011), 22.

Perfect Lives, 39.

Quoted in Thom Holmes, “Robert Ashely: Built for Speed,” The Wire, March 2014 →.

Perfect Lives, 11–12.

Outside of Time, 156.

Atalanta, 22–26.

Atalanta, 22–26.