“You must vadiar through the circle, you must go around the world several times until you can finally hit the other angoleiro right in front of you.”1 These words by Master Curió invite us to listen to and observe the key movements of capoeira angola—not to be confused with the competitive sport capoeira, which is reduced inevitably to a martial art.2 In defiance of traditional sense and conduct, capoeiras or angoleiros, the practitioners of capoeira angola, are taught to never move straight. To practice, capoeiras form a circle within which the players swing around and avoid direct confrontation, exploring the limited space in defiance of one another’s expectations, looking for the right moment to strike. This tradition, inherited from slaves, is much more than meets the eye, offering its practitioners knowledge beyond the mastery of a fighting style.

To enter the world of angoleiros, we return to the exhortation of Master Curió: “You must vadiar.” There are many ways to translate “vadiar”: to wander, to loiter, to idle away one’s time aimlessly. In Brazil, vadios or vagabundos, people engaged in vadiagem or vabundagem (vagrancy, idleness), have historically been associated with subjects produced by criminal codes and juridical discourses. After the legal abolition of slavery in 1888, these codes and discoures criminalized people who were not, for whatever reason, absorbed into the “free” labor system. Such people were construed as a problem for the maintenance of capitalism and the world of waged labor. As Saidiya Hartman says, speaking of the US context, which resonates in Brazil as well, “The advent of freedom was plagued with anxieties about black indolence that hinted at the need to manage free black workers by perhaps more compelling means … Named as offenses were a range of itinerant and intemperate practices considered subversive and dangerous to the social order.”3 The first Criminal Code of the Republic of Brazil, enacted on October 11, 1890, explicitly referred to capoeiras as if they were the same kind of threat to the post-emancipation capitalist order.4 Capoeiras were associated with “riots,” “disorder,” and “instilling fear of all kinds of evil.” However, like vadios, their crime was the non-valorizing use of public space (noted in the criminal code as “streets and public squares”). The practice of capoeira was not restricted to fixed locations, could be done anywhere, and didn’t need institutional establishments or any sort of enclosed spaces. Streets and squares were as good as anywhere else. Anxieties about Black idleness were synonymous with anxieties about the mobility of the freed. Indeed, capoeiras were identified as idle because they were doing something they were not supposed to do, and they were doing it in public space—mobile reminders of other forms of life.

There was the world of workers and honest people and the world of idleness and crime, an opposition that still survives in everyday language—when people command vagabundos to “go get a job,” or when “trabalhador” (worker) is used as a synonym for a virtuous identity. It is very common, for instance, for Black people from favelas in Brazil to shout that they are workers when police stop them in the streets and try to arrest them. “To hegemonic discourse,” the world of idleness is “marginal, conceived as the inverted image of the virtuous world of morality, work and order …, perceived as an aberration to be repressed and controlled so it will not compromise order.”5 Vadiagem and vadios were at the heart of this anxiety about non-virtuous people and their lack of engagement or interest in the moral ideals of the new labor system. In post-abolition Brazil, there was no room for vadiagem and the refusal of post-emancipation waged exploitation; public space only allowed for a straight line between home and the workplace. In other words, the people unable to move between these two points were outside the intended order of the city. So, if vadios were those persecuted and condemned for not living (working) as they are commanded to, for giving themselves over to a mobility identified as a publicly visible threat to the new system of labor, then claiming vadiagem in capoeira and other contexts was an act of de-subjectivization. The repetition of “vadiagem” in a space created by marginalized Black people turned it into a sign of pride: to talk of vadiagem or vadiação in capoeira angola is to talk of mobility and movement.

Master Curió and his father Master Zé Martins at one hundred years old, 2000. Amélia Conrado’s collection.

“You must vadiar through the circle.” In a sense, the circle (roda) formed by capoeiras is a restricted and clearly delimited space. If vadiagem is desirable and necessary inside such a boundary, how do we understand this demand for a criminal mobility that refuses authorized movement and the hegemonic framing of space? To move as a vadio is celebrated as a cultivation of bodily powers and creativity, as the enhancement of the body beyond the limits of the opponent’s imagination. This opponent, outside the circle of capoeira and practice, could be anyone trying to capture or arrest Black people, from the plantation to post-abolition urban spaces. Outside the circle, the opponent is unable to follow and properly understand what they can only view as a criminal mobility, something to be repressed. Criminality, when perceived in vadiagem, is something to be enclosed, contained, kept away from public order. However, the angoleiro, already engaged in vadiagem, is in a sense moving outside this particular construction of space. Outside and inside at the same time: a marginal movement that explores the fissures and gaps of visible space, for capoeira demands a “wisdom of the in-between.”6 To vadiar through the circle, formed in streets and squares, is a double act of vadiagem: in the eyes of authority, a refusal to use public space in the proper manner; in the movements surrounded by the circle of capoeiras, a gesture of refusal. And not only a refusal of the social order imposed by institutional command, but of a Euclidean understanding of space.

That is why “you must go around the world several times”: capoeiras must avoid linear movement and seek cracks in this hostile space, delving into them so they can swing around and learn how to defy prediction and capture, acquiring a new sense of space/spatiality to do so. Master Pastinha used to talk of Black people’s ways of avoiding capture as “playing tricks on one’s body,” swinging the body around as gingado or ginga, which, according to his book, is a “perfect coordination of bodily movements … executed with the intention of distracting the opponent, making him vulnerable.”7 The in-between, in the fissures produced and excavated in self-evident space, is the place where ginga is exercised “as creative potency.”8 But we can also say that ginga actively produces this space when capoeiras abandon straight lines and direct confrontation. In capoeira, movement never ceases.

Exploring multiple uses of space and the body in a smooth and flexible manner, one must produce confusion for those whose spatial understanding has not been transformed and expanded by ginga. “Ginga is dance, the principle of all movements, the sort of dance where they all come from,” teaches Master Virgílio da Fazenda Grande.9 Ginga is a fugitive dance for producing other fugitive movements; it is practiced as a condition for something else to happen—for making something else possible. The manufacturing of Black spaces within and against (post)colonial spatial order and geographical coordination is not possible without the collective discovery of what a body can do, of what can be done with it beyond and in excess of what it is commanded or authorized to do. In this sense, we talk of ginga as one of many Afro-diasporic principles of movement and the creation of space in the New World.

A Knowledge Written in Ginga

We can say that ginga demands a bodily empowerment that combines reactivation and invention: what colonial violence tries to eradicate must become enactable again so that the Black person can refuse the identification of corporeity with labor capacity; but, since the slave trade made people “change into something different, into a new set of possibilities,” the body also became open to more than the return and recovery of formerly held possibilities.10 Ginga is an exercise in inventiveness for those affected by the urgency of space-making against the intended death of Black sociality. It is more than something to be used against an opponent: it is a bodily study and investigation of possibilities previously unfelt and deemed inexistent. Per Achille Mbembe, “Power cannot be enclosed within the limits of a single, stable form because, in its very nature, it participates in the surplus. All power, on principle, is power thanks only to its capacity for metamorphosis.”11 This surplus, beyond what is given in colonial order, must be felt in excess of a forced perception of the entirety of a body’s possibilities, and for that reason it must be discovered and appropriated: it is the most fundamental condition for becoming other than a slave. If “Black” is “a nickname, a tunic that someone else has dressed” us in, using violence to trap us within it, then “a separation always exists between the intended meaning of the nickname and the human person who is asked to shoulder it. It is this distance that the subject is called on to cultivate, even radicalize.”12

Between what is intended and what is possible, ginga emerges as a principle of cultivation. Following Neil Roberts’s Freedom as Marronage, just as fugitivity can be thought of as a “condition of becoming,” the continuous, incessant exploration of mobility in capoeira can be figured as a nonlinear series of “expanses that bend and meander in their extension into space … unlike vectors in mathematics that follow in straight lines.”13 Gingado is a fugitive style designed to make the Black body ungovernable and to expand its powers beyond enclosure, allowing capoeiras to avoid capture by police and other adversaries. Gingar is “to be always escaping, always dodging, to never be in a fixed point,” per Master Ciro.

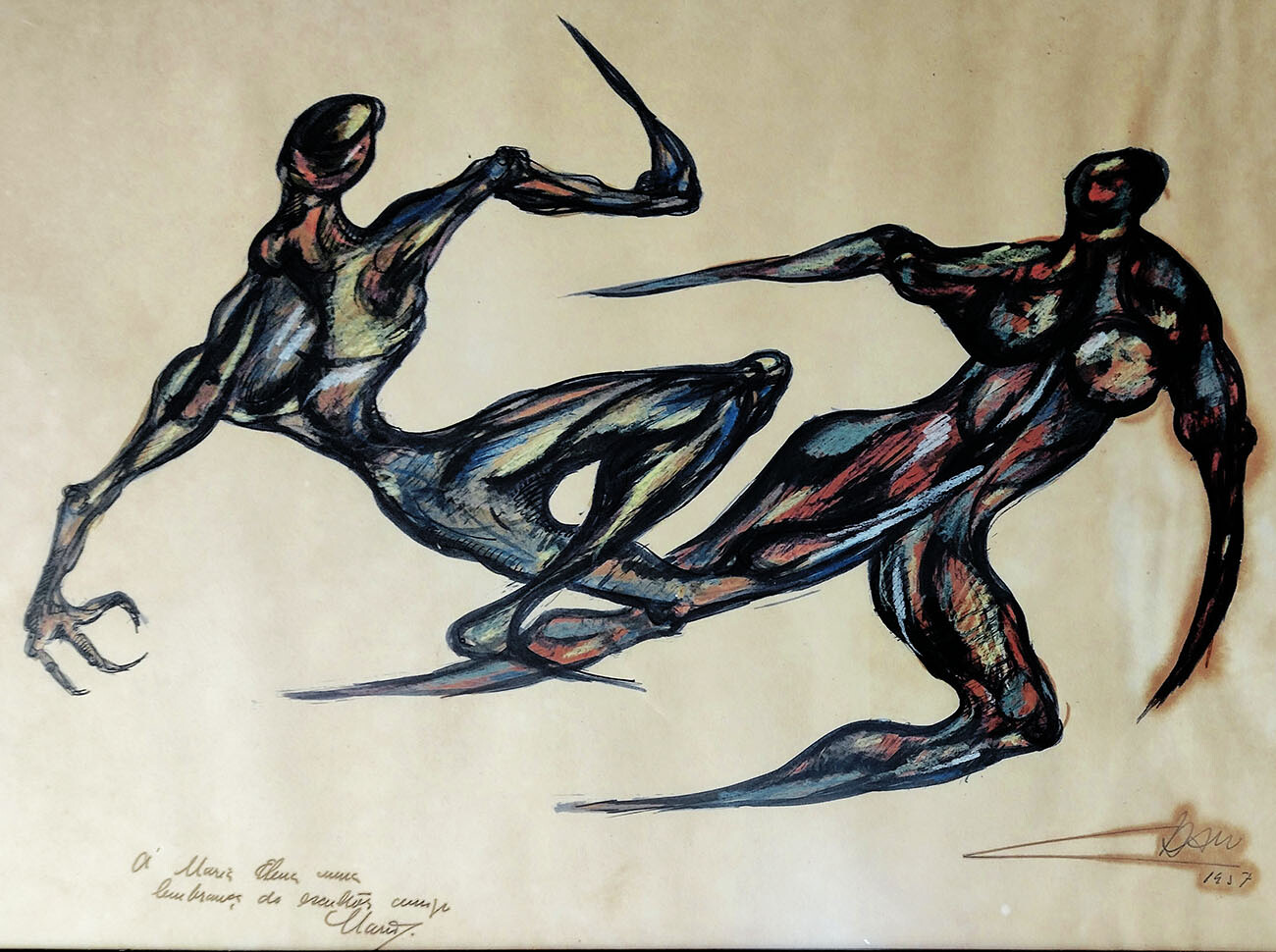

Maria Auxiliadora da Silva, Capoeira, 1970. Mixed media on canvas, 69.5 × 75 cm. Courtesy Museu de Arte de São Paulo.

Outside the circles of capoeira, this nomadic and errant style reminds us of the classical carioca (meaning “from Rio”) embodiment of a practical wisdom of the streets: the malandro (rogue, vagabond). A local manifestation of the vadio and a kind of antihero in Rio de Janeiro’s popular imagination, “the malandro doesn’t vacillate, doesn’t fall nor slip,” sings Bezerra da Silva.14 Adopting a lifestyle that celebrates all sorts of behavior and activities criminalized and associated with vadiagem, the malandro exhibits a mobility we also find in capoeira. Taking the ancient sophist Gorgias as an example, Muniz Sodré states that the practitioner of capoeira angola is someone who has attained another sort of excellency/areté, typical of the malandro: “perceiving what is opportune and what is not,” while being capable of “evaluating the circumstances” without recourse to “universal norms.”15 “The practitioner of capoeira must be calm, serene and rational.”16 In order to avoid slipping or falling, both malandros and capoeiras have to remain unpredictable, but capable of patiently identifying the right moment to strike—and to escape.

This practical knowledge is spatial knowledge. Within a given space, capoeiras navigate according to an invisible geometry that presents itself through the mastery of gingado. That is how the real opponent becomes vulnerable: their expectations are embedded in Euclidean thinking, so the in-between space and non-straight mobility are offered as an enigma they won’t be able to decipher until it is too late—the capoerias have escaped. The effectiveness of ginga depends on the mastery of the art of negaça (ruse, an artifice designed to seduce and deceive). This complement to gingado, which can also be called a specific manifestation of gingado, is about messing with the opponent’s usual train of thought to make them vulnerable to what comes next. To do this, capoeiras make a series of bodily insinuations, “pretending to withdraw only to turn rapidly around,” “advancing and retreating,” or “pretending to not see the opponent so that he can be lured in.”17 They use expectations as a resource for manipulation. The “deceptive, incessant sway of the body” creates two possible outcomes: victory or escape.18 To effectively produce confusion and reach one of these outcomes, one must go against the usual expectations of rationality, constantly making the opponent believe that what is about to happen conforms to an order of movement that, invisible to their (in)sensibility, is actually being refused. Negaça is negation in affirmation, affirmation in negation, a false promise offered to deceive and increase the odds of winning. “It’s about disguising, hiding, looking for a way to become invisible” (Master Ciro).19 This is another meaning of “vadiar” in capoeira: doing something other than what one is supposed or expected to do becomes a “play of dexterity and malice,” an exercise of mobility “in which you pretend to fight, pretend so well that the concept of the truth of the fight dissolves before the spectator’s eyes.”20 The creativity of gingado is inseparable from the deceptiveness of negaça.

Capoeira angola privileges unpredictability over everything else. It cannot be taught from established formulas even when it is learned by imitation; its opaqueness is its strength. It is a process of asking: What can the body do? The answer is in the body itself, in the way it is given over to vadiação when it perceives how space can be created in movement. But not just any movement. The body of the capoeira was not born ready and does not conform to colonial images of the racialized body, for it must be produced in between and outside of hegemonic logics of valorization and meaning. It becomes ungovernable through self-mastery.

There is no capoeira without music, played during the brief existence of the roda (circle). The sacred berimbau (an Angolan musical bow) is always there, along with certain other instruments. Following its sound and its call, the angoleiros form a circle, ask for the instrument’s blessing, and begin to move. They are commanded by the berimbau of the Master, who plays a specific type of the intrument that is large and low-toned. This type of berimbau is known as a gunga. The gunga is eventually accompanied by two other types of berimbau, the médio (medium toned), and, after these first two sing their respective parts, the viola (higher toned, used for improvisation), all working together in syncopated unity.21 The improvised bodies follow sounds that are not predetermined: what will be heard and felt is not fully known beforehand. Their bodies interact with sounds and incorporate them. The space produced by gingado, a “bordering space, located in a territory in excess to what is normally experienced, can be mobilized and made available through the symbolic universe of the music, the rhythms and chants, the dramatic bodily expressions.”22 The roda de capoeira is affected by this symbolic universe, and a “magical condition” is produced to “distort time and space.”23 The measure of time is given by the vibration coming from the berimbaus, not by the clock, and the creation of space depends on the impact of these vibrations on the body, so it can be ready for a new knowledge by attaining a new sensibility. Whatever happens inside the circle comes from feeling the music “without concern for metric or rhyme.”24 Each roda opens this space and closes it when it is done, but the spatial knowledge remains in the body, to be used in any future situation. The body learns the ginga by incorporating the spirit of the music, “the feelings of the soul of the capoeiristas and the people being translated in the chanted verses.”25

Berimbau

Each roda is a remembering, a new beginning, the improvisation of a new body for a New World—the world the African came to with nothing more than a body and its memory. Space is created and recreated and remade at the same time that the body is transformed in ginga. Capoeira, with its diasporic, unrooted sense of space and spatial sensibility, may not create fixed territories (such as quilombos), but it offers a compelling view of the bodily conditions for creating new, improvised spaces in the fissures and cracks of normally visible space. These are ephemeral spaces, produced against the suffocating experience of the plantation and other sites where the Black body is subjected to violent instrumentalization. “The work for life,” says Achille Mbembe, requires the “ability to metamorphose.” He continues: “One must be ready to desert at any moment, to dissimulate, repeat, fissure, or recover.”26 Metamorphosis happens in the distance between the intended product of subjection and the possibilities to be discovered, and ginga allows for the cultivation of this distance. The body moves around the world several times before striking its opponent, exercising its metamorphic powers as it travels through improvised space—a breath of fresh air and a “response to those atmospheric pressures and the predictably unpredictable changes in climates that, nonetheless, remain antiblack.”27 All is done in the “service of harnessing that which is unseen to naked eyes.”28 And, since this creative use of body and space is inseparable from deceptiveness, it plays with expectations: those who impose and enforce a spatiality where the visible is the non-transformed, non-gingado Black body (the body intended for work, reproduction, and nothing else) cannot see what happens within and in excess of these enclosures. Against the official order of the visible goes the unseen, hidden, ephemeral, in-between space where the body moves in gingado.

The Angoleiro Body as Heterotopia

The gingado body belongs to the unmappable city. Its streets and squares are not the same places where the police go to arrest vadios and capoeiras for their criminal use of public space. The gingado has no place in the official city; it moves inside its fissures, deepening them and finding another space within them. In the first decade of the twentieth century, the city of Rio de Janeiro was redesigned by the mayor Pereira Passos to look more “modern,” i.e., European. The new Rio would be “like a sober, healthy organism,” claimed lawmakers, and the streets, being the “respiratory system of the city,” would be used to evaluate its health.29 These urban reforms, “authoritarian and entirely distant from the reality of the streets,” were part of a larger administrative, political project to eradicate Black and marginalized people’s spaces and forms of life, “giving up on their assimilation to invest in isolation.”30 “Through legislation, warnings, prohibitions and condemnation … the official world mobilized a silent war against the symbolic universe that the world of the malandro carioca was made of.”31 In other words, the new Rio de Janeiro was intended as a space inhospitable to vadiagem. “This organization of the city understands circulation through policing good and bad circulation” in the name of public hygiene.32 This policing promoted the social Darwinism pushed by reactionaries and conservatives, which aimed to legitimize the logic of racialization and criminalization.

“Moving through zones of shadow between the fairy lights of a new age, … in the darkness of life in favelas and ghettos,” many of the malandros learned capoeira as a means of self-defense.33 Before that, capoeiras organized secret groups called maltas, using their own signs, greetings, and dress code, creating the aesthetics that eventually got them associated with malandros and malandragem: “baggy pants, coat suits, and silk scarves.”34 In the Criminal Code of 1890, belonging to a malta was listed as an “aggravating circumstance,” and police/state repression eventually, after a few decades, led to the extinction of these organizations. But just as the malandros remained active and would soon become antiheroes of the new Rio de Janeiro, the practice of capoeira, criminalized until 1940, stayed alive as an art of resistance and a rite of improvisation, reinstating, over and over again, the possibility of a Black social life against the imposed order of the city. This improvisational navigation of cracks in official, inhospitable space remained as an oral tradition stored in Black bodies, each generation remembering what the body can do in excess of what configurations of power and authority intend for it. Policing circulation and public space was a strategy doomed to fail: the knowledge of space-making carried in the body remains there, along with the sensibility for vadiação required in non-straight mobility.

Enslaved and free Blacks meet outside official history, in the invisible extension of visible space, where authorities have no place. The “bad circulation” threatening public order is only partially intelligible to the police: the play of appearances created by ginga deceives not only in the sense that the opponent cannot predict the capoeira’s next move, but also in the sense that it keeps their eyes focused on their own illusion of what it means to vadiar. The space created in gingado is closed to the opponent. Gingado and vadiação are still means to cultivate a bodily knowledge and a spatial sensibility that cannot be enclosed by the official city, a place designed to expel and isolate Black sociality in its diverse cultural manifestations. The existence of this design has never meant that everything unfolds in accordance with urban planning; capoeira has survived and thrived, and its masters and practitioners are still here. But their space-making is not intended to produce permanent, fixed territories in the visible city, nor even secret places with stable coordinates. The city of capoeiras, malandros, vadios, and others is unmappable, but it has always been there: its streets existed prior to the straight avenues of urban reform. Its labyrinth of curves is time and time again (re)discovered by bodies transformed by gingado. Undocumentable, the space created by this movement can be known only by those who feel it and breathe in its atmosphere.35

Many sayings of capoeira masters are transmitted orally, mostly during initiation and training practices, and have no written records to quote. Like many popular sayings, the moment when they were first uttered is unknown and, from an academic point of view, even their authorship is debatable. Unless otherwise specified, all translations are by the authors.

Born in 1937, Master Curió (Jaime Martins dos Santos) founded the Escola de Capoeira Angola Irmãos Gêmeos de Mestre Curió, with several branches in Brazil and around the world, starting in the city of Salvador (Bahia). He has received an honorary degree from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and other awards and honors from several institutions. Born into a family of angoleiros, he was the great-grandson of the legendary Besouro de Candeias, grandson of Pedro Virico (known as Curió, the nickname he inherited), and son of José Martins (Pena Dourada). He became a disciple of Master Pastinha at the age of eight.

Scenes of Subjection (Oxford University Press, 1997), 127.

See → (in Portuguese).

Sidney Chalhoub, Trabalho, lar e botequim: o cotidiano dos trabalhadores no Rio de Janeiro da belle époque (Editora da Unicamp, 2001), 78.

Luiz Rufino Rodrigues Júnior, “Exu e a Pedagogia das Encruzilhadas” (Phd diss., Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, 2017), 33, 40.

Mestre Pastinha, Capoeira Angola (Fundação Cultural do Estado da Bahia, 1988), 52. Born in 1889, Vicente Ferreira Pastinha learned capoeira when he was a kid from an “old African man” who saw him getting repeatedly beaten up in the streets. Master Pastinha was responsible for the codification, unification, and consolidation of the practice of capoeira angola, of its teaching and philosophy. His concepts eventually spread all over Brazil through his followers. He taught capoeira for forty-two years before officially founding the Centro Esportivo da Capoeira Angola (CECA) in Pelourinho, a place used for slave auctions in colonial Salvador (Bahia), its name a reference to the whipping post located in its main square where enslaved Africans were punished. CECA became a cultural hub for Black people, but in recent decades gentrification forced most of them away. Master Pastinha died in 1981, having spent his last days in Pelourinho mostly forgotten, helped by his wife Maria Romélia and a few friends.

Rufino, “Exu e a Pedagogia das Encruzilhadas,” 40.

Virgílio Maximiano Ferreira was born in 1944. He was introduced to capoeira angola by his father, Master Espinho Remoso, in 1954. He started his own capoeira classes in a neighborhood in Salvador called Fazenda Grande do Retiro after his father’s death. He was president of the prestigious Brazilian Association of Capoeira Angola (ABCA).

Édouard Glissant, Caribbean Discourse, trans. J. Michael Dash (University Press of Virginia, 1989), 14.

Critique of Black Reason, trans. Laurent Dubois (Duke University Press, 2017), 131.

Mbembe, Critique of Black Reason, 46.

University of Chicago Press, 2015, 144, 167–68.

The lyrics come from da Silva’s song “Malandro não vacila.”

A verdade seduzida: Por um conceito de cultura no Brasil (DP&A, 2005), 159–60.

Mestre Pastinha, Capoeira Angola, 35.

Mestre Pastinha, Capoeira Angola, 37.

Sodré, A verdade seduzida, 154.

Ciro Lima, now fifty-nine years old, founded the Capoeira Angola Studies Group in 1987 and was officially recognized as a mestre de capoeira by the late Master João Pequeno, a disciple of Pastinha, in 2001.

Sodré, A verdade seduzida, 155.

The cabaça, attached to the lower part of the berimbau and used to amplify sounds, is made of the gourd-like fruit of the calabasha tree, hollowed out, dried, and opened in a way that is often imagined as a talking mouth.

DPI/Iphan, Dossiê 12: Roda de Capoeira e Ofício dos Mestres de Capoeira (Iphan, 2014), 103.

DPI/Iphan, Dossiê 12, 103.

Mestre Pastinha, Capoeira Angola, 41.

Mestre Pastinha, Capoeira Angola, 41.

Critique of Black Reason, 144–45. Emphasis in original.

Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Duke University Press, 2016), 107.

Ashon T. Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (Fordham University Press, 2017), 2.

Claudio Medeiros, História da experiência das epidemias no Brasil (GLAC edições, 2021), 120–22. Emphasis added.

Luiz Noronha, Malandros: Notícias de um submundo distante (Relume Dumará, 2003), 102.

Noronha, Malandros, 102.

Medeiros, História da experiência das epidemias, 122.

Noronha, Malandros, 64.

Eduardo Stelmann Gambôa Júnior, “‘Vai trabalhar vagabundo’: A malandragem no banco dos réus” (undergraduate diss., Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, 2013), 29.

Inspiration for the idea of improvised space as undocumentable comes from Fred Moten, “revision, impromptu” →.