The movements of the stars have become clearer; but to the mass of the people the movements of their masters are still incalculable.

—Bertolt Brecht1The earth is local movement in the desegregation of the universal.

—Fred Moten and Stefano Harney2If you think technology will solve your problems, you don’t understand technology—and you don’t understand your problems.

—Laurie Anderson, 20203

1. Earthrise

On Christmas Eve 1968, the crew of Apollo 8 read from the book of Genesis as they orbited the moon, marking the moment with Christian cosmogony.4 On the same trip, the astronaut William Anders captured “Earthrise,” an image of the earth from lunar orbit, often described as an image that inaugurated the new environmental movement. The mission to explore the moon thus became instead a dramatic “discovery” of the earth, a perfect parable of the Promethean, or better yet, the Faustian return to Man himself, encapsulating all the elements of the threat of self-annihilation. On earth, what was to bring endless energy brought nuclear annihilation, and the same fossil fuels that enabled the Apollo mission into space brought destruction to the earth’s atmosphere.

But at that point, all that was solid melted into air. The sublime scene of the fragile planet seen from afar, floating in the sea of darkness outside violent human histories—it was a pure, perfect image, seemingly beyond ideology.5 The cosmological anthropocentrism underpinning this tilt in perspective was at the time described as the moment when humanity took God’s place.6 The Earthrise image signified a paradigm shift in humanity’s understanding of scale: a new aesthetic configuration emerged, centered on both the concept of planetary unity and planetary fragility. Moreover, what propelled this image to quasi-religious icon status was not only the “God’s-eye perspective” but also the fact that the image was created with the assistance of an advanced prosthetic technology of vision.

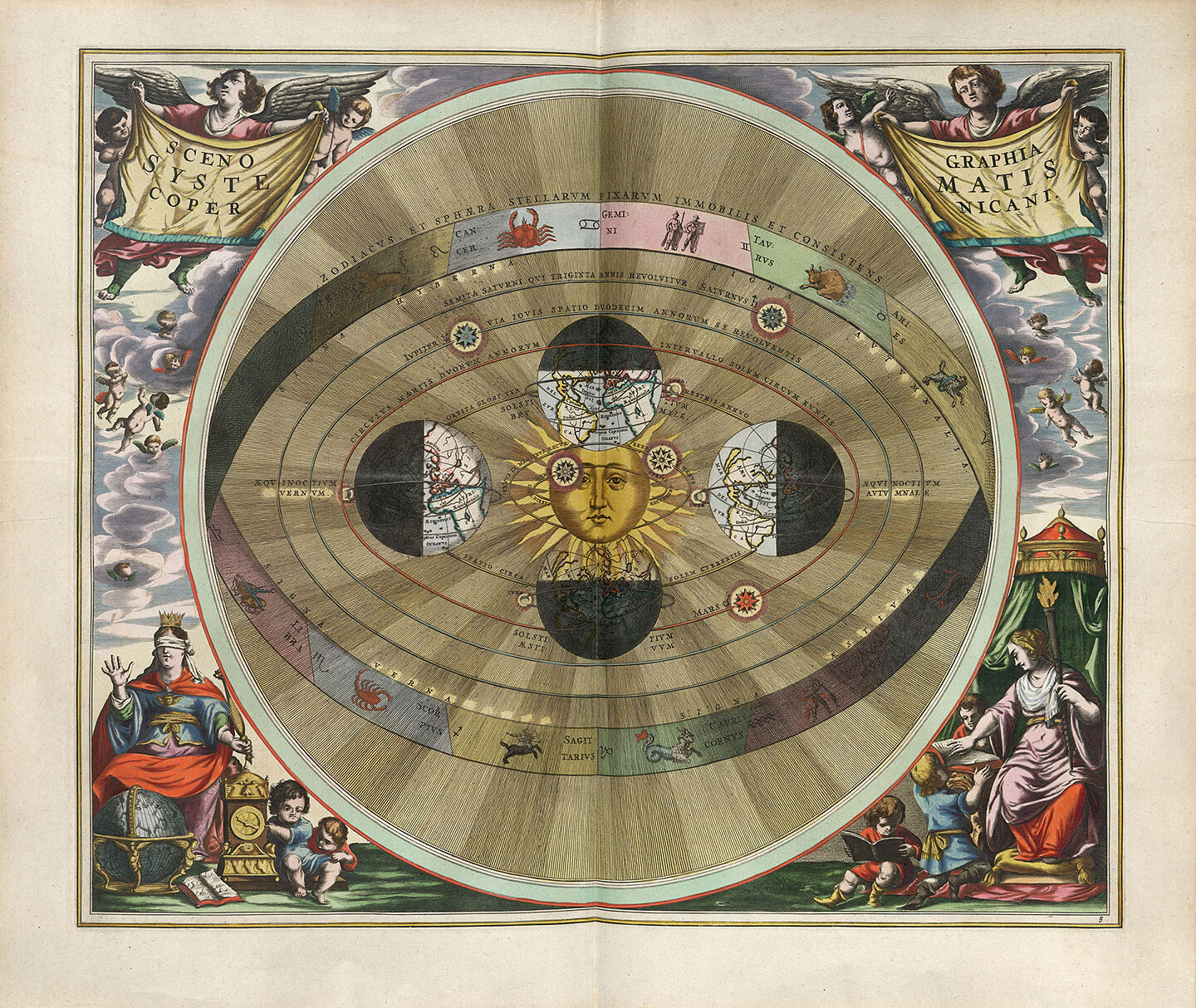

The “whole earth” image provided a fantasy of wholeness and closure—even though it showed merely a part of a pole and less than half of the planet. That is unsurprising, since as humans we will always have only a partial view, and there will always be something left out. This means that the most straightforward answer to Steward Brand’s canonical question “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole earth yet?” would be: because it is simply not possible. Nonetheless, the perspectival, scalar shift implied by the Earthrise image was immense, arguably equal to those conceptual shifts brought on by Copernicus, Darwin, and Freud.7

What interests me is how this particular image and its onto-epistemological underpinning and political framing prefigured the normalization and naturalization of technological paradigms for planetary climate representation and computational environmental governance. Earthrise not only signaled that the earth was now to be understood as whole, as a governable techno-social-biological system, but that, as such, it was to be managed as a computable problem, a problem for which a master algorithm could be created and solutions found. While the actual computational power behind the launch of the Apollo missions was miniscule compared to today’s digital computational technologies, the earth itself became the key protagonist in a much larger shift: the ever-expanding paradigm of Western computational thinking as a mode of reasoning that approaches and formulates problems in such a way that their solutions can be effectively executed by an information-processing agent—in other words, by computational steps and algorithms.8

Astronomers using globe models of the moon to plan the Apollo mission, 1962.

I want to argue that this episode in the genealogy of the techno-positivist fantasy of the master-human, as manifested in the context of the US-American Cold War worldview, is a clear prefiguration of the Anthropos behind what has, in the meantime, been denominated the “Anthropocene” (by a consortium of Western “earth scientists”).9 This Anthropos—the Western liberal Subject, the techno-solution-oriented possessive individual who was supposed to be the ultimate incarnation of the godlike master-manager—instead proved to be an exceptionally poor manager of this “system” in the course of the remainder of the twentieth and the start of the twenty-first century. Now, in the face of climate breakdown, the fallen Anthropos is attempting to recreate himself in the image of God once again, his wet dreams of planetary computational governance in the Anthropocene fueled by artificial intelligence, geo-engineering, terraforming, and mysterious black holes.

2. The Black Hole

The images of the late-sixties Apollo missions are emblematic of the Pax Americana moment: the redemption and reconstruction of Man through techno-scientific reason after European genocide. But another, more recent cosmic image could be taken as a symbol of the nihilistic, postapocalyptic vacuity of the libidinal and material investments of that same normative Subject after the Fall. In April 2019, the significance of the Apollo crew’s view of earth from space half a century earlier was dramatically inverted. In a coordinated news conference across the globe, researchers unveiled the first visual evidence of a black hole. The tiny picture of this black hole, designated M87, once again pushed beyond the previously established limits of what humanity was technologically capable of seeing. The project, named Event Horizon Telescope, linked together eight existing radio telescopes located at high altitudes around the world, from the Spanish Sierra Nevada to Hawaii’s Mount Mauna Kea.

Giant virtual telescopes like this are able to construct such images because effective aperture is equal to the distance between the two most distant stations. For the Event Horizon Telescope, the two most distant stations were at the South Pole and Spain, creating an aperture nearly the same diameter as the earth. The telescopes all had to focus on the same target, in this case the black hole, and then collect data from their locations, providing a portion of the Event Horizon Telescope’s full view. Each telescope was precisely synchronized with the others using an atomic clock locked onto a GPS time standard. What was essential to produce the image of the black hole, and therefore to visually prove its existence, was to combine and analyze the data from the various sources computationally. This means that the pallets of hard drives carrying petabytes of raw data from the telescopes were flown in from eight locations around the globe and combined using specialized supercomputers.10 The data from all eight sites were then synchronized using the time stamps and combined into a single image. Finally, the image was generated by an algorithm developed for MRI technology, which “stitched together” the visual data and filled in gaps by analyzing the surrounding pixels.11

Composite image of black hole M87, 2019. Credit: Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration.

This is to say that what the telescopes captured was not an actual photographic record. Instead, it was a huge amount of other data along with that of the black hole. Constructing the image thus became an enormous task of sorting that required so-called artificial intelligence to identify and single out the image of the black hole. The computational process, whose carbon footprint has so far not been calculated but is no doubt immense, crunched calculations across eight hundred CPUs on a forty gigabit-per-second network for several months. The result was a computationally generated representation of warped light around the black hole’s accretion disk. Moreover, as this light falls outside the human visual spectrum, a decision had to be made about whether to add color to the representation. But how else to accommodate human vision, which in Western hermeneutics is so intrinsically related to the production of reliable evidence? Eventually, the scientists settled on an orange-red color to represent the swirly luminous flux.

The image primarily circulated on our screens, populating social media with ironic memes comparing the picture to everything from a cat’s eyes glowing in the dark to a burned pancake or a stovetop. While Generation Z remained mostly indifferent or at least devoid of reverence for the blurry depiction, techno-positivist members of Gen X, born around the time of the Apollo missions, gleefully celebrated the moment when the earth itself finally became a giant sensing machine.12 The weltschmerz-y, dark allure of a computationally produced image of a black hole, and the metaphysical pondering it generated among the latter generation, seems like a good example of alienation as a form of existentialist dread, as opposed to any concrete historical, material predicament of dispossession and alienation back on the broken earth.

The Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA) is an astronomical interferometer consisting of sixty-six radio telescopes in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile. It observes electromagnetic radiation at millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths.

3. Mauna Kea

A couple of months after the image of the cosmic hole appeared, Mount Mauna Kea in Hawaii, the site of one of the astronomical infrastructures that contributed to the production of the image, became the center of a protracted struggle over control of the land and conflicting cosmologies.13 In July 2019, three months after the Event Horizon Telescope operation, access to the summit of Mauna Kea was blocked by a protest against the construction of a giant $1.4 billion Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT). Since Mauna Kea is one of the finest places in the Northern Hemisphere for telescopic astronomical research due to its high elevation, dry environment, and stable airflow, it was selected as the site for the enormous telescope. The TMT, an initiative of several universities, with government-level support from Canada, China, Japan, and India, would be thirty meters in diameter, eighteen stories high, and accompanied by another two-thousand-square-meter building.

The Mauna Kea volcano, currently inactive, is one of the most sacred places for many Native Hawaiians, who consider the mountain to be their living elder sibling, born of Wākea, the Sky Father, and Papahānaumoku, the Earth Mother. The summit is a place of central importance in the local cosmogony, as it is believed to be where the gods reside and not a place for daily contact or habitation—much less a location suitable for a megastructure of Western techno-science. As one elder explained: “Just because we do not have a large cathedral up there, or an actual building that says that this place is sacred, does not mean that it is less sacred.”14 Mauna Kea is also a sensitive site that is home to Hawaii’s largest groundwater basin and the habitat of numerous endangered animals and plants. As Camille Kalama, a Native Hawaiian civil rights lawyer, put it, “Science itself doesn’t just get a free pass. It needs to be balanced with what does it impact [sic] and how does that benefit the world that we live in and move us forward … Hawaiians support science, but science also needs to be contextualized.”15 Kalama’s words seem to echo the knowledge of ancient Hawaiians who lived on the summits of Mauna Kea and harvested the dense volcanic-glacial basalts to create tools, while relying on its vast forests for sustenance, before European colonizers introduced cattle, livestock, and wildlife, disrupting the volcano’s ecological balance. Colonial land grabs and exploitation were followed by Western techno-science infrastructures and resistance against them, which, in the case of telescopes on Mauna Kea, far predates the TMT. Hawaiians have been protesting interventions since at least the 1960s, before the University of Hawaii installed the first telescope on the mountain. The already existing infrastructure of the Mauna Kea Observatories is located on the summit, within a special land-use zone known as the Astronomy Precinct, which was established in the sixties, around the time of the Apollo mission to the moon. At that point the cosmological colonization of Hawaiian land was already taking place, one cosmology overwriting and foreclosing the other.16

Protestors block the road leading to the construction site of the Thirty Meter Telescope on

Mauna Kea, 2020.

4. The “Anthropocene”

The Anthropocene hypothesis, introduced some time between the Earthrise image and the black hole image, should be read as yet another reified form of scientific knowledge that reproduces hegemonic, techno-solutionist discourse and Western computational thinking in the broadest sense. I want to briefly turn to a canonical text on the Anthropocene written at the turn of the millennium by Paul J. Crutzen and Eugene F. Stoermer, which argues that human activity has become a significant geological and morphological force since the time that the last geological epoch, the “Holocene,” was named in 1833.17 It seems symbolic that the authors’ first reference for the Anthropocene hypothesis is the concept of the “noösphere,” introduced in the late 1920s by a Darwinian geologist, a Jesuit priest, and a metaphysician who was a Bergson disciple. The noösphere concept, the authors suggest, is crucial to their own postulate of the Anthropocene, because it recognizes the increasing power of humans as part of the biosphere and emphasizes the “technological talents” that will be crucial in shaping the future and the environment.18

After offering the latest statistics on ecological devastation, Crutzen and Stoermer propose that the Anthropocene began with the introduction of the steam engine in late eighteenth century England, only to finally declare that

without major catastrophes like an enormous volcanic eruption, an unexpected epidemic, a large-scale nuclear war, an asteroid impact, a new ice age, or continued plundering of Earth’s resources by partially still primitive technology (the last four dangers can, however, be prevented in a real functioning noösphere) mankind will remain a major geological force for many millennia, maybe millions of years, to come.19

To reiterate, they believe that the plundering of the earth by “primitive technology” can be prevented by a real functioning noösphere. At the end of the programmatic section, the authors advise that

to develop a world-wide accepted strategy leading to sustainability of ecosystems against human induced stresses will be one of the great future tasks of mankind, requiring intensive research efforts and wise application of the knowledge thus acquired in the noösphere, better known as knowledge or information society. An exciting but also difficult and daunting task lies ahead of the global research and engineering community to guide mankind towards global, sustainable, environmental management.20

The reader is to comprehend that by applying the knowledge generated by information society and—drawing on Darwinian theories from the late 1920s—by managing the population, humanity can continue to exploit the planet for millions of years to come, albeit in a more technologically sophisticated manner.21 In other words, the designation of the Anthropocene as such combines a diagnosis with a clear prescription for a solution, in the form of engineering and Western techno-science. The text thus casts Western technocrats and scientists in the dual role of those who can bring about a dramatic recognition of climate change and those who are the only ones in a position to fix the problem.22

The Earthrise, the black hole picture, and the Anthropocene are the fetish objects of techno-positivist ideology. These abstract totalizations, like all universals, are (to invoke Gayatri Spivak) hard to refuse, even as they continue to exclude so many of us earthlings. Whether one is inside or outside the time frames or optical regimes they set up, one is caught within a universal that attempts to measure and calculate everything, from the infinite, fluid, deep time of the earth to the rapid, rigidly structured clock time of computational processing, banally measured in the mere number of rule applications.

5. The Oikos

The triumphalist rhetoric of Pax Americana that followed the Second World War asserted a narrative of the victory of rationality over reason, with the United States coming to the rescue of what was left of humanity “after evil.”23 This “rescue of humanity”—again figured as Western, white, “civilized”—was to be a joint project of political science, sociology, psychology, and economics. The reconstruction of Europe was formulated as a path to a new rationality, to be achieved by expanding the sphere of instrumental reason via rational choice, economic rationalization, and expanded computation into the domains of political decision-making and the molecular details of everyday life. Rational choice, exercised freely by an educated and well-informed populace working in concert with the know-how of experts, as instantiated by a flourishing of interdisciplinary think tanks, was the American method of resurrecting normative humanity by building a technocracy with a human face. In conjuring this “new human”—the renewed Anthropos—the high frontier of outer space, beyond the messy, historically haunted confines of the planet, seemed a perfect habitat. This was the Prometheus of the new liberal Enlightenment, dramatically performing reason in the extraplanetary agora.

Poster by See Red Women’s Workshop, 1974.

A 1958 book by Hannah Arendt, titled The Human Condition, was highly influential in the consolidation of this new rational Subject of liberal humanism. In this text, Arendt takes up the distinction between handeln (praxis) and herstellen (poiesis) and develops the character of these activities on the basis of the ancient city-state (polis) as it appears in Aristotle’s Politics. Handeln takes place in the public sphere of the polis, while herstellen and arbeiten (work) belong to the sphere of the private economy—the space of unproductive labor, the space of social reproduction, the ancient oikos. The strict separation between the private and public spheres ensures that the material constraints and necessities of organic life are kept out of the public sphere and that the polis can therefore be a meeting place for “free and equal people” to exercise their right to “the political” in a transparent, frictionless space of rationality. For Arendt, an anti-feminist, the Subject of this handeln, of techno-management, and of the political is the “Aristotelian man,” a living creature defined by its/his possession of logos. The polis, in which this individual operates, is seen as a guarantee against the futility and transience of the life of mere subsistence. It is a space protected from all that is transitory, with the aim of granting men immortality, at least in the realm of abstract ideas. In the Aristotelian model, women, children, and the enslaved belong together in the space of the oikos, not only because they are property, but also because they are understood as instruments for sustaining the performance of reason in the polis. The most fundamental political distinction was thus made between the inmates of the oikos and their masters, who moved freely in public space, performing activities worth seeing, hearing, and remembering. As feminist praxis has demonstrated, there is actually a complete interdependence between oikos and polis, or rather there is no polis as a discrete sphere of human activity. The polis exists only as a phantasmatic space of free Men’s law.

Arendt’s work was preceded by that of the German legal theorist and Nazi Party member Carl Schmitt. In his 1950 book The Nomos of the Earth, Schmitt asks how the earth is going to be divided in the future, in postmodernity.24 Schmitt develops a Western political history framed in terms of the idea of nomos—the “law”—and the spatial order achieved through the division and distribution of land. Nomos, from the Greek nemein as preserved in the German word nehmen, “to take or seize,” also signifies the capture or appropriation of the world as a whole, both as space and as material resource. Nomos is a direct function of the Aristotelian oikonomia, expanded beyond the individual “household.” The Roman Empire was in many ways the expansion of the Greek polis from the discrete boundaries of the various city-states into the ambition of a universal, cosmopolitan cosmo-polis. And it was Roman law that laid the foundation for European law, which, in the order of medieval feudalism, was as international as the canon law of the Roman Church, in which the vestiges of the empire persisted.

The law of seizing and grabbing expanded into a proto-planetary nomos as new colonial empires spread across the globe, bringing brutal exploitation, expropriation, and enslavement. The universalism of twentieth-century liberal technocracy reproduces this law as the “techno-nomos,” which becomes the nomos of the earth suitable for the Anthropocene. In it, a newly reconfigured political theology is presented as a depoliticized techno-positivism that continues to abstract and “economize” nature—including the biological human species—as capital and renders the entirety of world ecologies as instruments or sites of extraction available for the catechesis of technological solutions that overcome all limits to growth.

In the late 1960s, the new environmental movement, based on the recognition of the whole earth, saw the earth as an ecosystem. This idea of the ecosystem replaced the openly racist Malthusian prophecy and the social Darwinist legacies of population control. Thus, local and concrete cases of devastation on earth were subsumed under the idea of a global ecosystem, which somehow needed to be managed and controlled like an engine whose broken parts occasionally have to be repaired and whose overall functioning has to be optimized. In the “vast machine” of our neoliberal earth, capital distributes agency across diverse configurations of technologies of control, management, and optimization. Under the current techno-nomos, the land grabs, labor, and social relations behind techno-scientific processes disappear in the flat ontologies of a digital vitalism in which the task of thinking is relegated to technological systems. In smooth, techno-logical, automated rationality, there is no space for the inhabitants of the oikos, or for that which is materially common to human life and other forms of life.

6. Earthly Labor

My extremely granular and rudimentary proposal here is based on three episodes from different registers of techno-scientific “post-ideological” reification: the Earthrise image, the black hole image, and the Anthropocene hypothesis. This proposal stems from my recognition of the need for a historical-materialist critique of the Subject and discourses on technology in the time of climate breakdown, but at the same time points out that this critique needs to be grounded in a consideration of the labor and the intelligence of those excluded from the planetary polis, those inhabitants of the ancient oikos in the broadest and anti-patriarchal sense, meaning the oikos that reproduces life and webs of life. This means that, yes, climate breakdown is a result of capitalist accumulation and its instrumental view of both nature and technology, but in order to tackle it, we must first address the cosmological and politico-epistemological grounds and dominant subjectivity that sustain this equation. Therefore, as fundamentally important as it is to say that ecological destruction is a condition of possibility for capitalist expansion, it is also impossible to start any project of critical engagement with the current entanglement between capital-sustaining technologies and the climate catastrophe without explicitly engaging with the Subject (Anthropos) of liberal humanism as a foundational project of twentieth-century Western cosmology. It is precisely this worldview that has limited the human species, severed our horizon from that of our fellow species, and precluded the imagining of what we might call a truly planetary freedom.25

That computational power has the capacity to make visible the magnitude of climate breakdown does not make the complex entanglements behind it more thinkable. Rather, in many ways, climate data aggregation and computational climate modeling actually forestall the ability to grasp the imbrication of the Western concept of technology—as well as actual technical systems—in the collapse of earth’s climate. The hegemony of the Western computational, techno-scientific, “aggregate data” representation of complex and fundamentally incomputable problems, such as climate breakdown, is in fact a “silent” epistemology. This epistemology fundamentally underpins the working of big tech companies, which, while developing machine learning at breakneck speed, are positioning themselves in the race to develop “green solutions” while simultaneously deploying AI to optimize the extraction of remaining fossil-fuel resources.

Artificial intelligence, just like extractive technologies before it, conveniently forecloses the history of land grabs, racialized and gendered labor, and the “labor” of nature, as well as the collective intelligence and unconscious working-together emphasized in theories of the general intellect.26 This is perhaps most evident in companies with symptomatically post-Fordist names like Cognizant, which receives hundreds of millions of dollars from Facebook to hire armies of content moderators, or what the company opaquely refers to as “process executives.” Of course, alienation occurs in Google’s new Bay View campus as well, where the transparent walls create a “neighborhood feel.” But the real shift is the unprecedented alienated labor that happens in the bedrooms and kitchens of Mississippi, Kenya, Nepal, India, and the Philippines, or wherever there is a profitable combination of fast bandwidth and low wages. This is where “taskers,” mostly women, spend hours on the most mind-numbing tasks—deciphering the emotional content of TikTok videos, labeling pictures for self-driving cars, staring through the eyes of robotic vacuum cleaners, or creating the precious “human-feedback data” used to train DeepMind’s chatbot. Many do this labor between sessions of breastfeeding or other social reproduction and care work. Their tasks are small components of much larger, extremely opaque processes, about which they are kept in the dark. This previously impossible alienation of earthly labor is what enables so-called artificial intelligence. The taskers, spread across the broken planetary skin, are the new oikos of the earth in the image of the negative theology of digital capital. This is an opposite image to that of the whole earth as a system in a state of absolute visibility—its inversion: oikos filled with the wretched of the earth in a state of complete obscurity.27

7. The Incomputable

Let us keep in mind the messy, dusty oikos of the earth in order to also keep in mind the extraction, exclusion, and exploitation obscured by the image of the technologically contained totality of the earth yielding to planetary computational governance. While it is true, as Spivak says, that “the globe is on our computers. No one lives there,” it is also true that the structural violence at the heart of real abstractions suggests that we do indeed “live there,” in the totalizing computational integration of foreclosed labor swallowed by the black hole of capital.28

I propose to rethink our instrumental relation to both nature and technē from the perspective of that originary technicity of the oikos, together with its relation to labor and knowledge, seen not as something that is produced and acquired but as something to be recollected, as something already there as a social praxis at the foundation of the planetary general intellect. The essentially feminist intervention I am making here implies thinking from the perspective and the logic of the instrument,29 by approaching technē from the episteme of this new oikos of the earth: not as the patriarchal enclosure that should be abolished but the unruly, incomputable, unreifiable space capable of resistance and joy. Importantly, this cannot be done by introducing the techno-logical into the space of the oikos. It must be based on the onto-epistemological recognition of the myriad unseen, organic intelligences outside the nomos of reason that is the intellectual property of free white men pondering the Blue Marble from outer space, gazing back into a black hole, or declaring the age of the Anthropocene.

Freelance “click workers” performing piece work in an internet cafe in the Philippines. They are sorting and labeling information to train large language models.

Technological Faustianism and the Arendtian elevation of the political to a rarefied sphere of supposed autonomy from material production have a history, and that history, like so much of history, is rife with violence and nihilism. This worldview cannot simply be “repurposed” as a liberation project in times of planetary breakdown. Instead, the political-epistemic project of liberation should be conceptually aligned with what in computation resists algorithmizing and the linear production of results. Thinking from the point of view of the incomputable means analyzing the recursive logic binding “artificial intelligence” and “artificial earth.” Unlike the computable, which can be either a prerequisite for the reductionist conceptualization of techno-science in the service of statistics and capital, or an abstraction in the service of a different mode of organizing social relations (as is often the case in non-Western societies), the incomputable is concerned with the patterns that resist the repeatable axiomatics of value.

This dialectic could be illustrated by the form differentiation that takes place in the actual computational process: a function or problem is computable if there exists an algorithm that can perform the function’s assignment—meaning that a Turing machine can be programmed to compute the value of any input in a finite number of simple steps. In contrast, an incomputable problem (and there are an infinite number of incomputables) is one for which it is impossible to design an algorithm.

What makes incomputable problems uniquely perplexing yet generative is that they contain undecidable properties or require infinite computational resources, and as such have no practical application or value. Despite this, they crucially inspire theoretical insight and transversal thinking. More importantly, they require us to step outside the Western computational mode of thinking itself. In other words, incomputability destabilizes the mode of solving problems that can be posed, described, or named. Climate breakdown renders the earth itself incomputable. The simplest illustration of this is the fact that using climate models based on historical data becomes completely unreliable in predicting the future.

Thinking from the perspective of the incomputable also advances thinking about how to explode the logic of instrumentality from within.30 To pay attention to the incomputable is to call not only for valuing what has been devalued or unvalued by the force of permanent primitive accumulation, but also for a radically different politics of value and a reconfigured understanding of what “the political” is, not least through the denaturalization of mono-humanist technology and computational reason. What ultimately needs to be done is to salvage an understanding of the nature-human-technology nexus from the violent reduction of the logos, polis, and black hole of the Anthropos. The oikos of the earth against the nomos of the black hole.

The Life of Galileo, trans. Desmond Vesey (Methuen, 1960), scene 14. Borrowed from Alberto Toscano and Jeff Kinkle, Cartographies of the Absolute (Zero Books, 2015), where the quote was used as an epigraph.

“Base Faith,” e-flux journal, no. 86 (November 2017) →.

Invited as the first artist in residence at the Australian Institute for Machine Learning, Laurie Anderson commented: “One of my favorite quotes about technology is from my meditation teacher: ‘If you think technology will solve your problems, you don’t understand technology—and you don’t understand your problems.’ When people say the purpose of art is to make the world a better place I always think: better for who? Art is not medicine or science. It’s not about creative problem solving. If I had to use one word to describe art it would be freedom. I’m curious about whether this freedom can be translated or facilitated by AI in a meaningful way.” Quoted in Bruce Sterling, “Laurie Anderson, Machine Learning Artist-in-Residence,” Wired, March 12, 2020 →. The part of this quote that I use as an epigraph was originally quoted by Kate Crawford on X (formerly Twitter), April 1, 2021 →.

The year 1968 was a dramatic one across Cold War divides: the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., the escalation of the Vietnam War, civil and student movements in the United States, and the crushing of the Prague Spring by Soviet tanks. The men on the moon were a perfect distraction and uplift. The astronauts recited verses one through ten of the Genesis creation narrative from the King James Bible. Dave Williams, “The Apollo 8 Christmas Eve Broadcast,” nasa.gov, September 25, 2007 →.

Kelly Oliver, Earth & World, Philosophy After the Apollo Missions (Columbia University Press, 2015), 17–19.

Or, as the entrepreneur Stewart Brand phrased it at the beginning of his Whole Earth Catalog (1968): “We are as gods and might as well get used to it.” This saying was meant to describe the purpose of the catalog.

Laurence H. Tribe, “Technology Assessment and the Fourth Discontinuity: The Limits of Instrumental Rationality,” Southern California Law Review 46, no. 3 (June 1973); as quoted by Paul N. Edwards, A Vast Machine: Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming (MIT Press, 2010), 1.

This is not to imply that computation and abstraction are anthropologically universal.

Paul J. Crutzen and Eugene F. Stoermer, “The ‘Anthropocene,’” in Global Change Newsletter, no. 41 (May 2000).

The supercomputers were located at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy and the MIT Haystack Observatory.

This corresponds to the way images of the whole earth are produced today (by military and commercial satellites—“theory machines,” as Toscano and Kinkle call them), achieving the effect of wholeness: “Images of the ‘whole earth’ are today ‘composites of massive quantities of remotely sensed data collected by satellite-borne sensors.’” Cartographies of the Absolute, 6.

Benjamin Bratton, a vocal proponent of speculative design, terraforming, and planetary computational governance, contemplated “the light emitted during the earth’s early Eocene period and only now arriving,” the “abyss in which we cannot see ourselves as we now understand ourselves to be,” and “the unconscious star-sucking void … blind and deaf to our orientations of horizon.” The Terraforming (Strelka Press, 2019), 21.

Quoted in a tweet by NBC Left Field, August 14, 2019 →.

Kristin Lam, “Why Are Jason Momoa and Other Native Hawaiians Protesting a Telescope on Mauna Kea? What’s at Stake?” USA Today, August 21, 2019 →.

The literature critically engaging with the TNT and the colonial techno-science on Mauna Kea by Native Hawaiian and Indigenous natural scientists and allies is growing. A good start is Sara Kahanamoku et al., “A Native Hawaiian-led Summary of the Current Impact of Constructing the Thirty Meter Telescope on Maunakea,” National Academy of Sciences Astro 2020, January 3, 2020 →.

“The ‘Anthropocene.’”

“The ‘Anthropocene,’” 17.

“The ‘Anthropocene,’” 18. Emphasis added.

“The ‘Anthropocene,’” 18. Emphasis added. This original text on the Anthropocene was followed by a slightly different version two years later, this time signed by only one of the authors and concluding with the more explicit prescription that “environmentally sustainable management during the era of the Anthropocene” may well involve “large-scale geo-engineering projects, for instance to ‘optimize’ climate.’” Crutzen, “Geology of Mankind,” Nature 415, no. 23 (January 3, 2002) →.

Crutzen, “Geology of Mankind.”

For a critical assessment of the Anthropocene hypothesis see, for example, T. J. Demos, Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today (Sternberg Press, 2017), 28.

Robert Meister, After Evil: A Politics of Human Rights (Columbia University Press, 2011).

The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum, trans. G. L. Ulmen (1950; Telos Press Publishing, 2006).

As the Combahee River Collective puts it: “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” “The Combahee River Collective Statement” (1977), BlackPast.org →.

For a recent theorization of the genealogy of the general intellect, see Matteo Pasquinelli, “On the Origins of Marx’s General Intellect,” Radical Philosophy, no. 206 (Winter 2019).

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox (Grove Press, 1963).

Imperatives to Re-Imagine the Planet (Passagen-Verlag, 2013), 44.

Antonia Majaca and Luciana Parisi, “The Incomputable and Instrumental Possibility,” e-flux journal, no. 77 (November 2016) →.

See my essay “The Anthropocene Hypothesis and the Incomputable,” in Incomputable Earth: Digital Technologies and the Anthropocene, ed. Antonia Majaca (Bloomsbury, forthcoming 2024).

Category

Subject

An expanded version of this text will appear in the forthcoming issue of Counter-Signals, edited by Alan Smart and Jack Henrie Fisher, with additional editing by Lola Pfeiffer.