It is also true that photography itself is an encounter with the fact that things are not what they appear. That they are in fact appearances. Eyes traveling through this occupation need to adapt to yet another kind of light. One with enough strength to expose and then decode the symbols of settler-colonialism that order one’s field of view: prickly pears growing over shattered limestone, expatriated palms and pines, color-coded rooftop water tanks, rose-red corrugated roofs, multibillion-dollar separation barriers, demolition rubble, expansive checkpoints, and bypass roads around shrinking enclaves of Palestinian-only areas. In other words, the ability to read the signs is part and parcel of decolonizing vision. So too is understanding the original fabric of historic Palestine so as to read through the layers of what has been erased and replaced against what has been appropriated.

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Pierrot, Formerly Known as Gilles, between 1718 and 1719. Collection: Louvre Museum. License: Public Domain.

Under the right conditions, each day contains two brief moments when the rising or falling sun hits at an angle so precise it arrests the eye. In this issue of e-flux journal, Oraib Toukan shows that there is more to what filmmakers and photographers call the “golden hour.” The unmistakable light of a brief interval also reveals things exactly as they are. In this time of Gaza’s devastation, Toukan explores the power and limitations of words and images in conveying the depth of Palestinian grief and dignity amidst what appears to be an ongoing ethnic cleansing. The grounding concept of turbeh (soil) emerges as an axis for knowledge and justice, urging readers to look beyond the surface and into the soil grain of images.

My point is not that the breakdown/insight model is fundamentally wrong. Those paralyses can provide a certain kind of epistemic gap for asking questions about what commonly comes as second nature. At the same time, it would be a mistake to rely on such an interval or space as a meta-structure for critical work. For example, a default move within the frame of contemporary art over the past two decades: defunctionalized objects pulled out of usual circulation or infrastructural location appear to offer a kind of freezing and deictic insight, as if a hunk of undersea internet cable on a gallery floor confronts us with the materiality of communication. Yet a moment of paralysis, or even of the decoupling of the informational from its material substrate or mechanism, does not automatically generate the kind of critical or political thought one might want to follow from it.

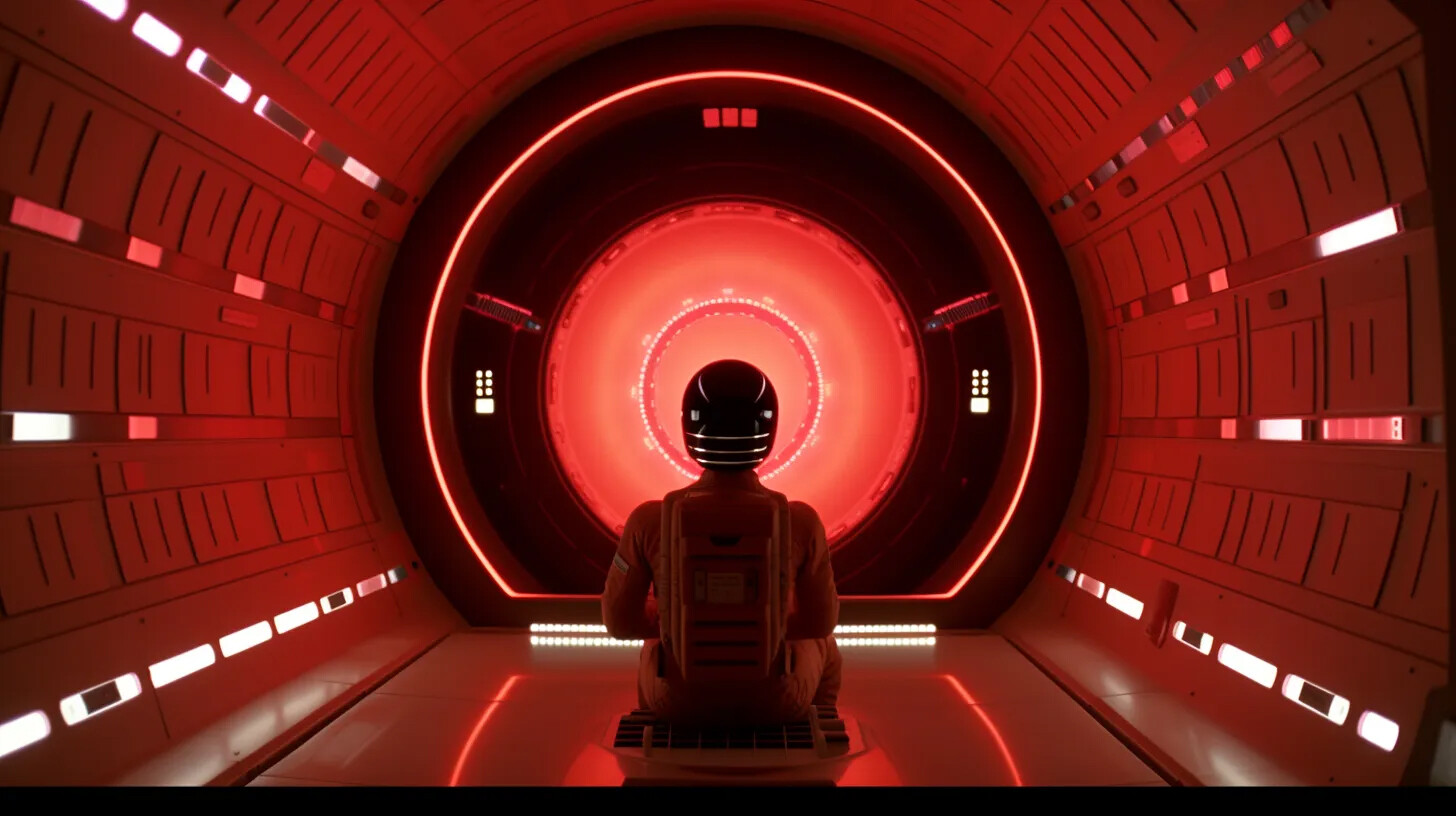

Human-made machines not only want their freedom from their makers but also want to deprive their makers of precisely what they want from them: freedom. The human voices in “Push the Button” are just about to be erased by machines that are in their homes, in their bedrooms, over their beds, hovering, opening, preparing to vacuum up their living souls. At this late point, the only thing that can stop this rebellion is pushing the button. (“I can’t program my machine / Now it wants to take my soul / Stop or it will proceed.”) The hope, it seems, is that the nukes (machines) will bomb us back to the land before time—or, more precisely, the gates of paradise. Here, where the curse began, we start all over again. This is the source of the track’s theological theme. Nature in “Push the Button” is God.

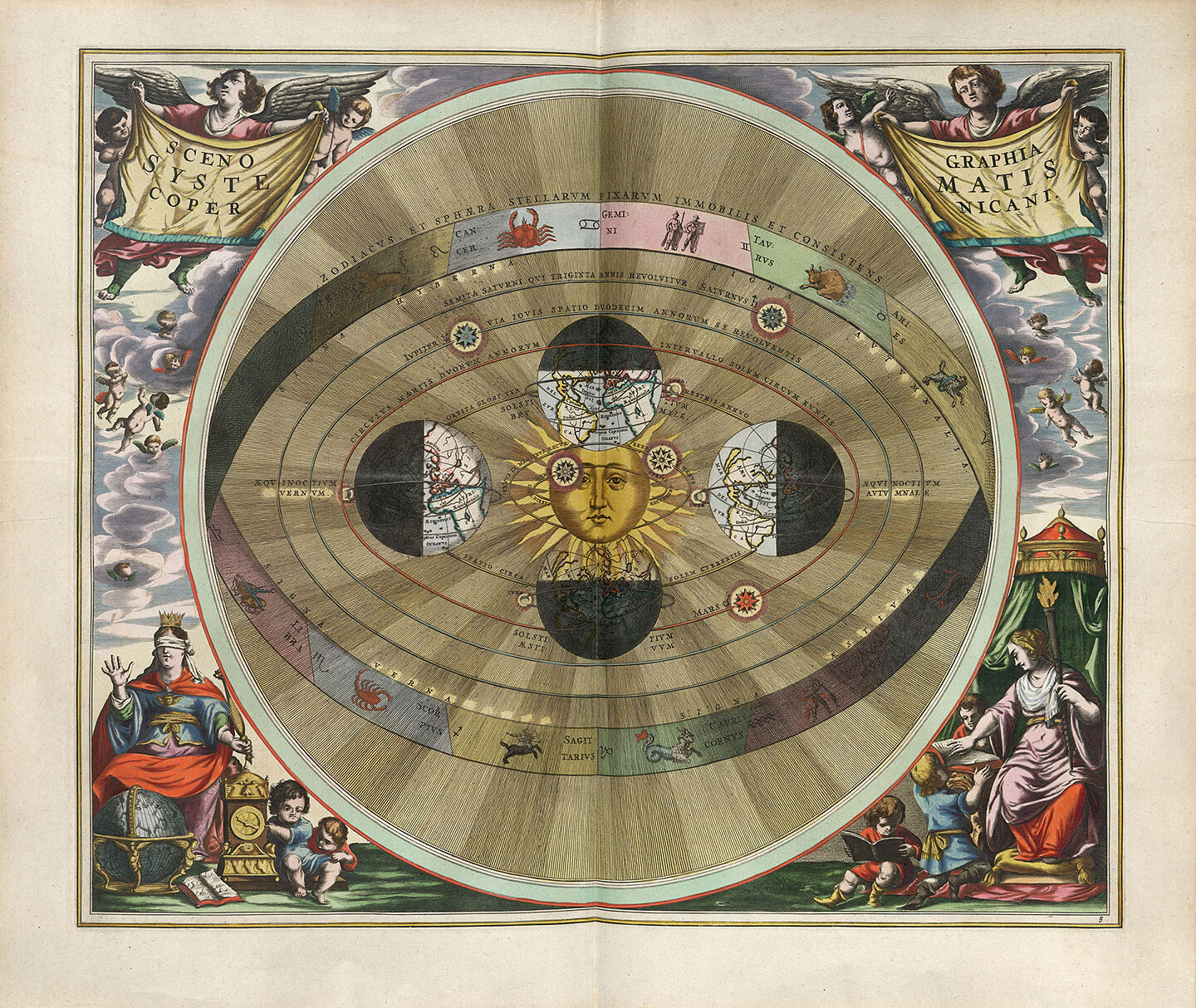

On Christmas Eve 1968, the crew of Apollo 8 read from the book of Genesis as they orbited the moon, marking the moment with Christian cosmogony. On the same trip, the astronaut William Anders captured “Earthrise,” an image of the earth from lunar orbit, often described as an image that inaugurated the new environmental movement. The mission to explore the moon thus became instead a dramatic “discovery” of the earth, a perfect parable of the Promethean, or better yet, the Faustian return to Man himself, encapsulating all the elements of the threat of self-annihilation. On earth, what was to bring endless energy brought nuclear annihilation, and the same fossil fuels that enabled the Apollo mission into space brought destruction to the earth’s atmosphere. But at that point, all that was solid melted into air.

If, as Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò warns, “climate apartheid” is on the rise, then Cop City Atlanta offers an ominous flashpoint. For not only is Cop City an exemplary story of the violent repression of community activism at the nexus of abolition, decolonization, and environmentalism; it also spotlights the forces of counterinsurgency that are operating to prevent any political transformation beyond the status quo. If the environmentalist movement is losing in the struggle to stop world-ending climate change, then continuing to focus on practices of ecological repair is increasingly myopic, even escapist, without taking into account the forces blocking any meaningful change.

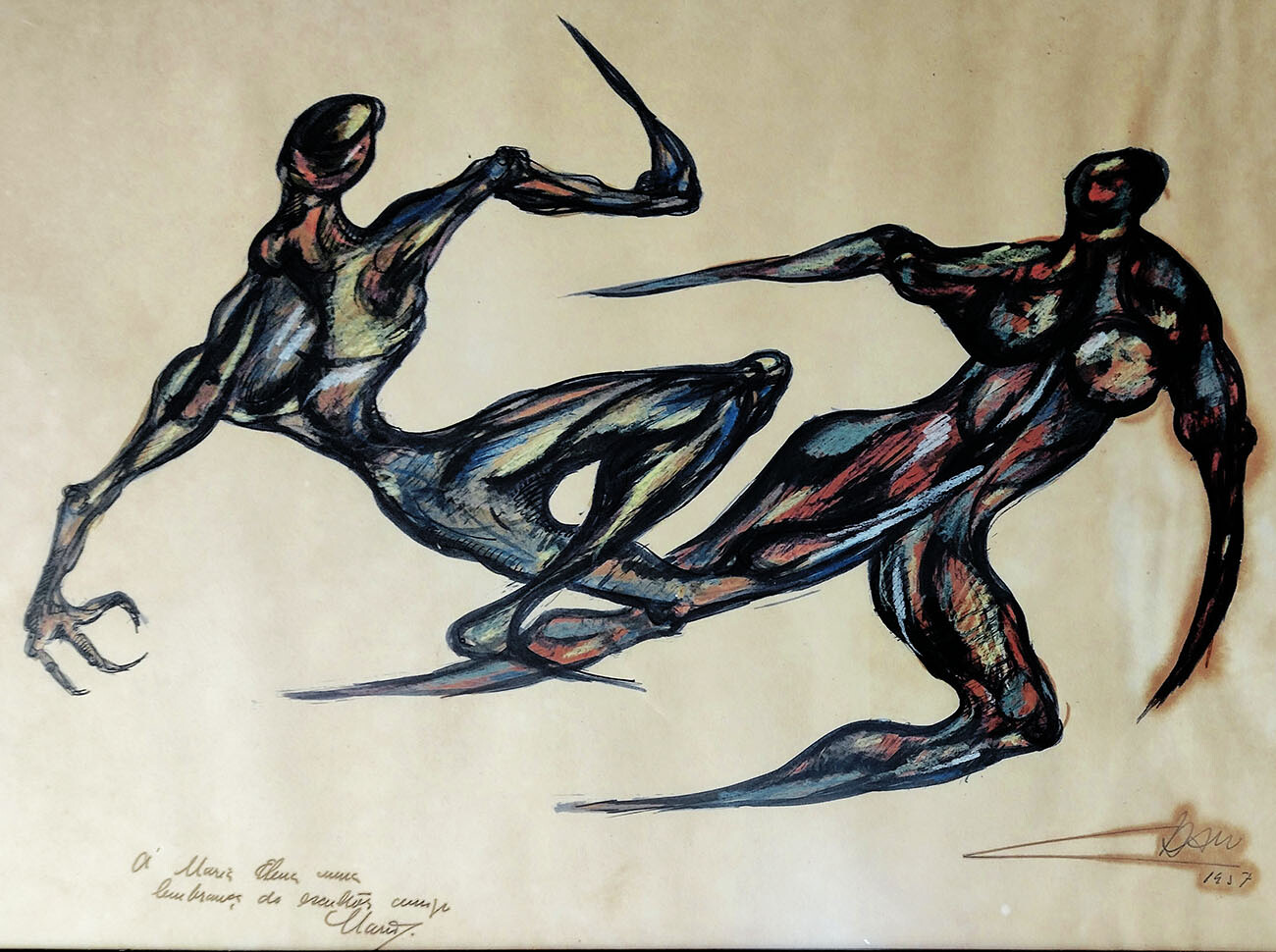

In defiance of traditional sense and conduct, capoeiras or angoleiros, the practitioners of capoeira angola, are taught to never move straight. To practice, capoeiras form a circle within which the players swing around and avoid direct confrontation, exploring the limited space in defiance of one another’s expectations, looking for the right moment to strike. This tradition, inherited from slaves, is much more than meets the eye, offering its practitioners knowledge beyond the mastery of a fighting style.

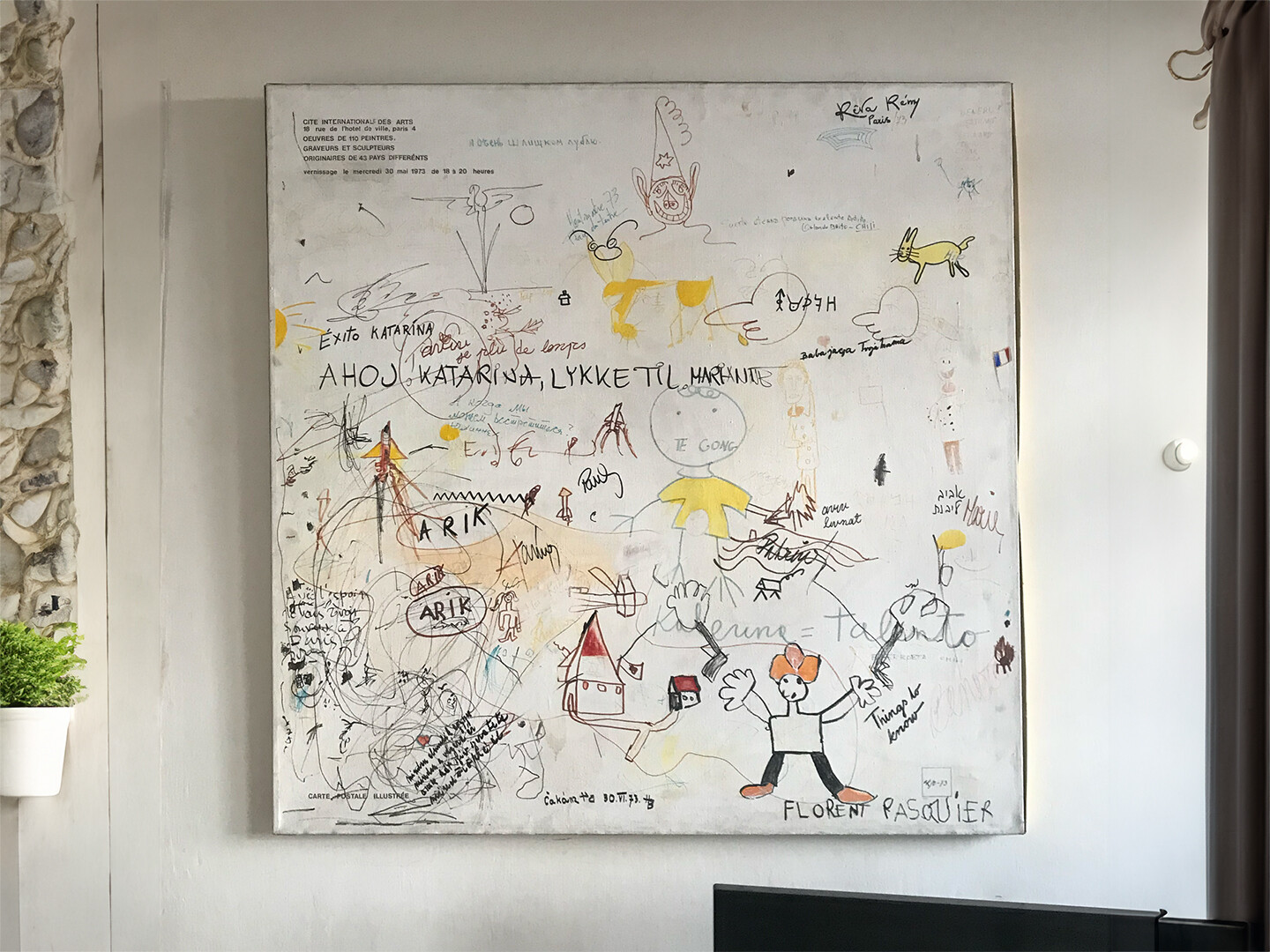

Without appealing to dogmas or causing any anxiety, art addresses facets of the unknown that hide other unknowns. Contrary to what science often assumes, mystery in art does not cater to obscurantism but instead opens minds. Mystery is one state of knowledge that the artist may actively use to contextualize and enrich rationality. Unlike other forms of knowledge, it maintains endless imaginative flexibility by disorienting and reorienting us.