My grandmother always said that if she hadn’t been an artist, she would have been a space researcher. For her, the cosmos was an intimate theme.

—Xenia Vytuleva-Herz

How did Anna Andreeva’s cosmic fabric designs from the 1960s, with their wildly experimental lunar, cometary, and planetary shapes, emerge from the deprivations of the Cold War planned economy in the Soviet Union? With Andreeva’s recent retrieval on the international art scene, most commentators have characterized her abstract, geometric patterns as signs of her individual drive and exceptional ability to circumvent the constraints of the Soviet system. Yet this interpretation reflects the assumptions of Western art histories of modernism, according to which that system always prohibited abstract experimentation and individual expression. We want to suggest the opposite: that it was precisely the collective Soviet art system that allowed Andreeva to emerge as a leader among her comrades at the Red Rose silk factory, and as a unique artistic voice. Her interest in the cosmos was both collective—ardently shared by millions of Soviet citizens caught up in the space race—and deeply personal.1

Andreeva was born into a wealthy family near Tambov in central Russia in 1917, the year of the October Revolution. Her elite class identity would bar her from entry to the Architectural Institute in Moscow. Instead, in 1936 she enrolled at the lower-status Textile Institute, leading to a storied, decades-long career as a fabric designer. She entered the Red Rose silk factory in Moscow in 1944 and would be awarded the prestigious Repin Prize for lifetime achievement in the fine arts in 1972.2

Anna Andreeva (left) with her textile artist colleagues at the Red Rose factory. This photograph was published in the Red Rose factory newspaper Chelnok, October 28, 1946.

The Red Rose factory was a conservative place in the 1940s, struggling to recover from the depredations of World War II. In keeping with the most hardline forms of socialist realism as they had been established by the late 1930s, fabric designs were expected to be highly realistic, to the point that floral designs depicted particular species of flowers naturalistically, such as tulips, peonies, pansies, and poppies.3 Images of the abundance and fertility of Soviet life dominated textile designs, including national folkloristic motifs from Russia and the Soviet republics. In 1948, for example, Andreeva produced a folk design of falcon hunting showing fantastical beasts within a flowing grid of abstract-vegetal borders.

By the mid-1950s, with the onset of the post-Stalinist thaw in Soviet politics, the Red Rose factory collective and the broader textile-artist community began to call for more innovative designs, including geometric patterns, to satisfy new consumer demands. In an article published in 1954 in the Red Rose factory newspaper Chelnok (“shuttle,” as in the weaving tool), textile artist A. Glotova wrote: “The suggestions and comments of consumers give the richest material for the creative work of artists. We concluded that workers must give greater attention to … the creation of geometric drawings and the use of folk ornaments.”4 The invention of new fabric technologies, including synthetic fabrics, also demanded modernized patterns. The International Festival of Youth, hosted in Moscow in 1957, became a stimulus for designers to shed outdated forms and invent new fabric patterns that would express contemporary Soviet themes to an international audience.5

Critics writing in the journal Decorative Arts of the USSR similarly called for innovation and modernization in fabric design, often using Andreeva’s designs as examples of the correct direction for the industry. In an article in Decorative Arts in the spring of 1961 entitled “New in Textile,” the critic I. Alpatova noted the “movement toward simplicity and laconism in patterns,” essentially tying fabric design to the so-called “severe style” (surovyi stil’) that had recently emerged in socialist realist painting, and which was often noted for its “laconism.”6 Alpatova also praised the appearance of more contemporary themes, national motifs, and geometric ornamentation in the new fabrics, signaling that geometric patterns were by no means excluded from the Soviet textile repertoire.7

She singled out for extended discussion an Andreeva design called “Ladoga” (an ancient town known as the first capital of the Rus’ people), a so-called national (narodnyi) motif that would be printed in multiple iterations over many years.8 It demonstrates Andreeva’s innovative formal strategies despite the traditional folk theme: it incorporates the heavy black contours and symmetry of national art of the past, but the ornamentation is not mechanically transferred from older styles. In the black and white version, the contrast of black on white in a bold pattern conveys the feel of the contemporary, and in the colored versions, the spots of color don’t align exactly with the black contours, and bits of the white fabric are left bare, creating what Alpatova calls a “double planarity.”

Alpatova similarly praises Andreeva’s contemporary “thematic” fabric design “Cheremushki,” a geometrically conceived pattern incorporating the abstracted, outlined buildings of Nikita Khrushchev’s new, mass-produced housing complexes (most famously constructed in the new Moscow region of Cheremushki), regularly punctuated by puffs of green treetops that, at a distance, form a geometric pattern of green diagonals across the reddish expanse of fabric.9 Once again, the areas of red, orange, yellow, and green dyes do not align perfectly with the black contours, and bits of white fabric are left bare. Her fabric design “Greetings, Moscow” mobilizes the “theme” of Moscow itself, with repeated schematic drawings of famous Moscow landmarks distributed across a checkerboard pattern of blue and white, or black and white, squares. Some of these thematic fabrics were projected into women’s fashions through Andreeva’s collaboration with her Red Rose colleague Natalia Zhovtis, the head of the factory’s artistic bureau, and fashion designers Nina Golikova and Alla Levashova from the Moscow House of Fashion—a collaboration described by critic and fashion historian Mariia Mertsalova in 1960 as the beginnings of necessary “collective work” between Soviet textile and fashion designers.10 Mertsalova’s article in Decorative Arts included fashion sketches of the “Ladoga” and “Greetings, Moscow” fabrics projected onto a woman’s dress and skirt, respectively. According to another critic in Decorative Arts, N. Kaplan, the latter fabric was hugely popular in the summer of 1961.11 As these examples suggest, even when designing patterns involving national motifs or representational “themes,” Andreeva displayed a proclivity for deft geometric ornamentation and visual experiment that was celebrated by critics.

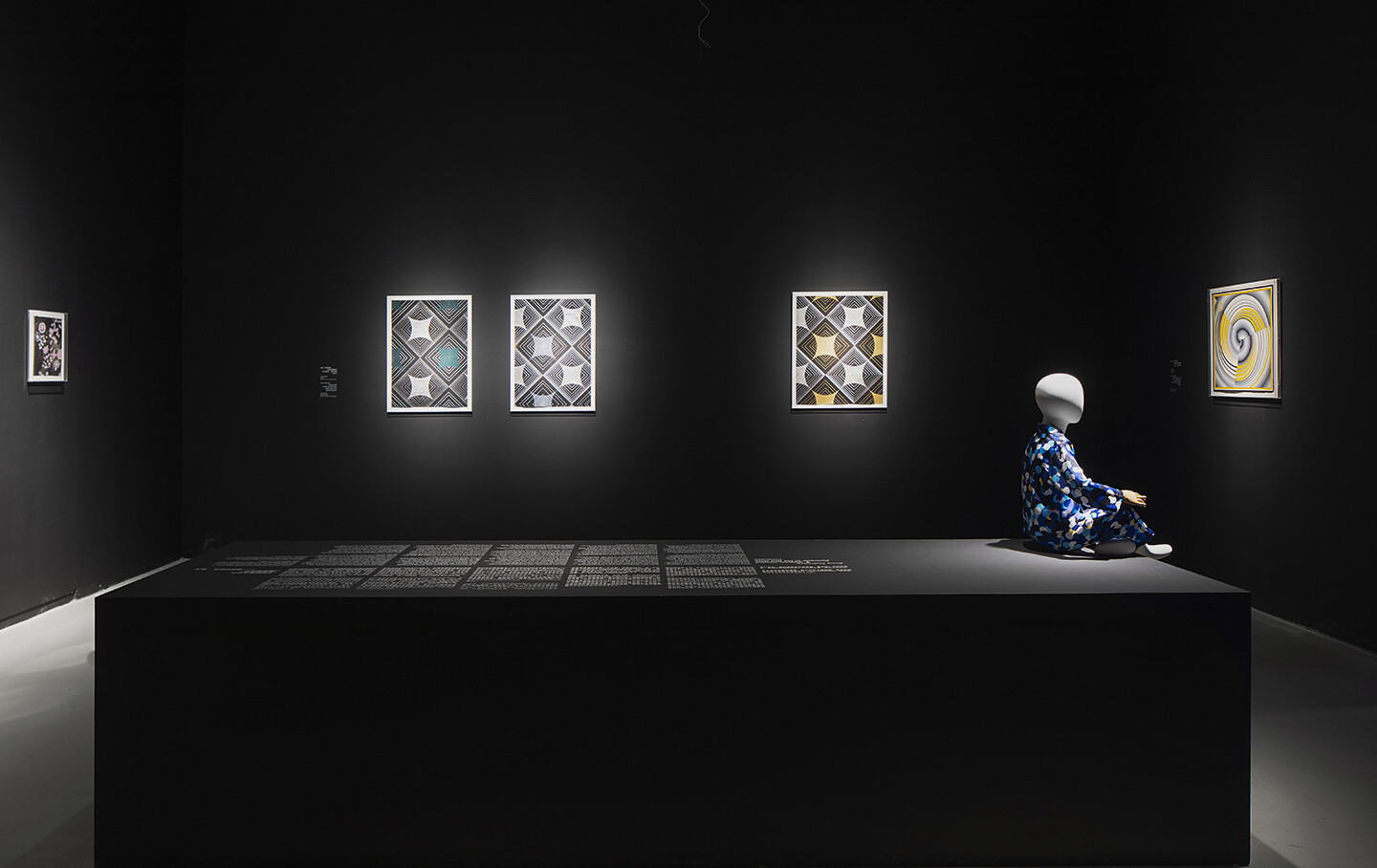

Anna Andreeva, Moon Eclipse, 1960s. Gouache and pencil on paper. Courtesy of the Estate of Anna Andreeva & Layr, Vienna. Photo: Power Station of Art.

There are early signs of Andreeva’s interest in the cosmos. For example, a 1958 drawing titled Stars-Flowers shows bursts of tiny gold flowers whose white centers cascade into showers of white dots against a dark ground, turning the floral design into a vision of comets against a starry sky.12 But the definitive shift toward cosmic designs seems to have come with a commission she received in 1961 to create a silk scarf to commemorate the first manned space flight by Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin on April 12, 1961. Such luxurious silk scarves, usually intended as official or diplomatic gifts, were a Russian tradition extending back to the nineteenth century; the Red Rose factory, with its specialization in silk production, was often tasked with such commissions.13 The Gagarin scarf design is perhaps less formally adventurous than her innovative fabric patterns. Four horizontal bands alternate between two strips in gold showing the densely packed buildings of Moscow—as if the separate drawings of landmarks in her earlier “Greetings, Moscow” design had been compressed into a single, shining mosaic—and two strips of black sky with typical white star shapes, interspersed with the words “Cosmos” and “April” and the numbers “12” and “1961,” all bordered by texts reading “Glory to the first cosmonaut in the world Yuri Gagarin, April 12, 1961.” Her design thus visually links Moscow with outer space, to emphasize Soviet domination of the space race.

Soon after designing the scarf, she would meet Yuri Gagarin himself. She was sent to the UK as part of a delegation of twenty-three Soviet clothing and textile designers to participate in the Soviet trade fair at the Earl’s Court Exhibition Centre in London, which ran from July 7 to July 29, 1961. Gagarin visited Earl’s Court on July 11, 1961, the first day of his triumphant five-day tour of the UK, where crowds thronged around him.14 The highlights of the trade fair were the section dedicated to space exploration and the fashion shows. A photo published in The Times shows Gagarin at the fair in front of a replica of a Soviet satellite and a portrait of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the Russian rocket scientist who pioneered astronautics, while another shows him grinning widely as he is surrounded by giddy Soviet fashion models, who made a splash in the fair’s twice-daily fashion shows. One of them wears a dress in a fabric with large, stylized poppies against a polka-dotted ground representative of the kinds of modernized floral designs that the Soviet textile industry aimed to produce at this time. A writer for a Liverpool newspaper wrote admiringly about the fashion shows at the fair, but wondered, with some justification, whether the fabrics and clothes on show were really mass produced, or only made in limited quantities for precisely such showcase events.15

As if to allay such doubts about the mass production of modern fabrics in the USSR, a certain “blonde Madame Olga Lashkova,” a member of the textile delegation on a visit to a Manchester factory, is cited in a local newspaper: “I am surprised that the big floral designs, which are too realistic … are still popular here. In Russia they are out of date. We go for simpler designs.”16 This article was accompanied by a photograph of Andreeva, identified by name, at the Manchester design center.17 According to Andreeva’s family, she also accompanied Gagarin on a visit to the royal palace, where the silk Gagarin scarf produced from her design was presented to Queen Elizabeth as an official diplomatic gift.

We can speculate that her experience designing the scarf and meeting Gagarin—and indeed the epochal event of Gagarin’s space flight itself—spurred her interest in cosmic-themed designs. In this she was not alone; Soviet material culture of this moment was bursting with space-race objects, including the Saturn vacuum cleaner, the Sputnik electric samovar, the Rocket Lamp, and space-themed postage stamps. Scholarship on Soviet space-inspired material design has focused largely on such objects, with almost no attention given to textiles and fashion.18 Postwar textile design has in fact been largely absent from the historiography of Soviet material culture, including what we might call the Soviet branch of “space-race fashion”: clothing design, the invention of new synthetic fabrics, and the development of new fabric patterns thematically dedicated to cosmic themes, such as those of Andreeva.19 In 1963, the name “Kosmos” was given to a new type of synthetic fabric with a corrugated surface developed by the Central Scientific Research Institute of Silk and intended for clothing production.20 It would be developed into a whole family of synthetic fabrics under the same name. I. Chizhonkova designed slim-fitting jumpsuits with helmet-like textile headgear in a rare Soviet interpretation of what were called “missile suits” in the West, whose sleek lines likened the wearer’s figure to a rocket. While Western “space-race” designers preferred white and shimmering surfaces, Chizhonkova bet on bright red and blue. In the winter of 1967–68, her designs were published in the Soviet album Moda (Fashion) with a caption suggesting that, in the future, such costumes might be worn on “the dusty paths of the Moon.”21

Andreeva’s cosmic fabric designs are less literal than space suits or Saturn vacuum cleaners. Celestial bodies are circular geometric forms or splashes of color on black grounds, invoking the wonder of deep space in a poetic rather than technological register. Her floral comets are like bursts of flowers thrown up into the air, flying against a background of starry sky or northern lights. Her moons and vortexes and planetary forms suggest more the vision of a person who gets up in the middle of the night to watch a once-in-a-century eclipse or comet, or a researcher looking through a telescope, than the specificities of sputniks and astronauts. She spoke with her family about her interest in space and natural phenomena such as lightning from a young age, and of her perhaps romantic notion that she would have been a space researcher if she had not been an artist—a desire that may have arisen partly as a response to her intensely intellectual and loving relationship with her husband, the mathematician Boris Andreev. In conversation with him, and in collaboration with her daughter Tatiana, she would go on to experiment with more cybernetic cosmic designs in the 1970s, introducing regularized patterns of rhomboids into her customary circular forms.

Anna Andreeva, 1/2 of the Moon, 1961. Ink and gouache on special gosznak paper. Courtesy of the Estate of Anna Andreeva & Layr, Vienna. Photo: Power Station of Art.

A second scarf design that she made in 1961 to commemorate Gagarin’s flight—which, as far as is known, was not produced—is exemplary of her experimental renderings of cosmic themes. Much like the other scarf design, it is organized into four horizontal strips separated by borders with text (“Glory to the cosmonauts—cosmos 1961—1/2 of the moon”) but gone are the Moscow buildings and the recognizable star shapes, replaced by rows of pure circular shapes. The bisected circles clearly evoke the moon, especially with the text “1/2 of the moon” helping that perception along. Yet the drawing is more a rigorous graphic experiment with variations of color across an irregular pattern than an image celebrating technological space travel, and the vivid shades of orange, pink, and purple stray far from the conventional yellows of the moon, suggesting the more intimate and affective nature of her relation to the cosmos.

Her more personal cosmic-themed works participate in the broader Soviet mania for space travel, but they offer an alternative to the kind of triumphalist and technocentric Soviet space imagery of sputniks, spaceships, rockets, and half-naked muscular male bodies carrying hi-tech devices that dominated official space-themed designs. On the contrary, most of Andreeva’s cosmic designs—other than the 1961 scarf commissions—do not refer at all to humans or human-made technologies. Her cosmos is a place not to be conquered technologically but to be imagined on its own terms. In the tradition of the Russian philosophy of cosmism, with its utopian and technically unspecific dreams of resurrecting all the dead fathers buried on earth and resettling them on distant twinkling planets, we might say, borrowing from Robert Bird, that she is cosmic-minded, rather than space-race minded.22

We can speculate that the artistic council tasked with selecting the final scarf design for Gagarin in 1961 opted for the one that most directly linked Russian power (through the lustrous gold Moscow cityscape) to space travel (through the representation of the familiar starry universe). This was, after all, the primary purpose of a commemorative scarf destined to become a diplomatic gift. Yet there is no reason to assume, as a number of Andreeva’s Western commentators have done, that there was an inherent problem with the abstract or geometric nature of her alternate “1/2 of the moon” design. Designers routinely submitted such designs—whether related to the cosmos or not—to factory artistic councils for approval, and many were mass produced throughout the 1960s and ’70s.23 The operations of such councils, however, as well as the rigorous structures and processes of the selection and production of textiles within the planned economy, remain opaque. Research into the textile design of this era is just beginning, having been neglected, as we have seen, in the historiography of Soviet material culture. Yet primary sources, such as the publications Chelnok and Decorative Arts of the USSR, can begin to alert us to some of the dominant structures and problems of the system within which Andreeva worked at the Red Rose factory.

Textile artists, and the artistic councils that selected designs for production, were under pressure to meet the demands of production plans decreed by the Soviet of Ministers of the USSR and the Central Committee of the Communist Party.24 A notice in Chelnok from 1960 states that artists and the entire factory collective are working to complete the seven-year plan for textiles ahead of schedule. As part of this push to achieve the plan, artists and fabric technologists entered into a competition sponsored by Mossovnarkhoz (the Moscow Soviet for the National Economy) for the best textile factory, submitting seventeen new fabric designs and sixteen new kinds of fabric to the competition jury.25 A photograph accompanying this notice shows Andreeva, along with Zhovtis and two other colleagues, who are “pleased that their designs for the competition have been printed on fabric.” A Chelnok article the following year explains that the factory has a textile laboratory, and within it, a so-called “assortment group” that analyzes the assortment of fabrics produced at the factory and “creates good conditions for more effective research into raw materials, weaving, and so on”—accompanied by a photograph of the group, including Andreeva.26 She consistently emerges as a leading member of this busy and well-organized collective.

Yet there are also signs of the pitfalls of the Soviet planned economy: necessary materials were in short supply, and textile artists found themselves at odds with other members of the factory collective, and with the wider networks of distribution and trade. Artists would see their designs radically altered, especially in their color, once they reached the chemists and color technologists who would finalize the designs for production. In a Chelnok article in 1965, Zhovtis reports on exciting new designs by factory artists approved at a recent city-wide artistic council, only to add, in a signal of trouble ahead, “Of course, we want all of our approved drawings to ‘see the light of day’ in their original form, unaltered for production. But their further fate will depend on chemists and technologists.”27 The problem was that high-quality dyes were in short supply, and fabrics often got produced in dull colors that consumers didn’t want. A scolding lead article in Chelnok from the factory leadership in 1964 urges the artists and colorists to consult with consumers about their desired colors, because piles of Red Rose fabrics are languishing on store shelves, “‘frightening’ the consumer with their dreary color.”28 An anonymous little article written from the artists’ side in the same issue seems to respond to these accusations from management, by acknowledging that consumers are not buying the fabric “Pskovitianka” (woman from Pskov) in the unappealing colors in which it has been printed, so Red Rose artists are busy reworking it in brighter colors. Yet the article also casts doubt on the very possibility of such a reworking, quoting one of the younger fabric designers at the factory: “‘The trouble is,’ says artist Irina Sudenova, ‘that we don’t have the kinds of dyes for printing fabrics that would please our customers, especially women.’”29 Working within the tightly planned collective, artists cannot influence other sectors, such as those that produce or procure dyes.

Natalia Zhovtis took the artists’ frustration with the system public in a coauthored 1961 article in Decorative Arts, combatively titled “Who’s Right? A Letter from Textile Artists.”30 Andreeva is tacitly included as a member of this letter-writing collective, because the article was published against a background of her fabric “Cheremushki.” The letter lays out the “escalating dispute” between the textile industry and the workers in the trade sector who make the decisions about which fabrics to buy from factories and actually distribute to stores and clothing manufacturers. The letter describes “a strange phenomenon of the last two-three years”: buyers exclusively order older patterns, claiming that this is what the consumers want. Thus many Soviet textiles—including Andreeva’s designs—were produced repeatedly over a period of many years, while the new designs that artists worked so hard to make “contemporary” remained at the drawing stage. The notations on the back of Andreeva’s design drawings indicate that their year of conception was often separated from their year of production by five to ten to twenty years. The aesthetic ambitions of artists to meet contemporary consumer desire—including cosmic-themed patterns in the 1960s—were thus continuously foiled by other workers in the system who also had to meet their quotas in the plan, such as buyers who were nervous about trying to sell untested novel patterns to consumers, or seamstresses who preferred to work with familiar fabric patterns rather than having to redesign their clothes to accommodate new ones.31

Despite Andreeva’s spectacular success within this complex system, in which her designs consistently reached production, it appears that few of her cosmic patterns were printed, for reasons that are not yet entirely clear. It is possible that the extended lag time from design to production negatively affected space-themed designs, because the mania for all things space related abated somewhat after the US moon landing in 1969—in other words, after the USSR was no longer winning the space race. Only two printed fabrics have so far been identified that can be securely tied to Andreeva’s cosmic design drawings: a rust-colored fabric printed in the 1960s incorporating her half-moon designs combined with fragments of her stepped “cybernetic” or mathematical patterns, and a circular striped pattern printed in 1970. The latter seems to emerge from Andreeva’s multiple cosmic-themed drawings, such as a watercolor sketch from her “Comets” series of 1961–62, whose horizontal brushstrokes seem to set the circular celestial body into spinning motion. This sensation of movement is achieved in the final printed fabric through the op-art effect of a shift in the lines between those in the floating circles and those in the background. This particular fabric is also an instance where Andreeva’s cosmic patterns intersect most directly with the experimental geometric fabrics designed by her avant-garde predecessors in the 1920s, such as constructivists Varvara Stepanova’s and Liubov Popova’s designs of striped circles.

Anna Andreeva’s designs “Ladoga” (top) and “Greetings, Moscow” (bottom) projected onto women’s fashions, in Nina Mertsalova, “Costume and Fabric,” Decorative Arts of the USSR no. 8, 1960.

Anna Andreeva, design for a scarf commemorating the space flight of Yuri Gagarin on April 12, 1961. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Yuri Gagarin meeting Soviet models from the fashion show at the Soviet Trade Fair, London, July 11, 1961. Source: ČTK

The material culture of the Soviet space race: the Sputnik samovar, 1960s.

“Glory to the Conquerors of Space,” 1962. This postage stamp depicts the monument by Lev Lavrenov and Grigory Postnikov erected in Monino, Moscow Region, 1962.

This image of I. Chizhonkova’s space-race jumpsuits appeared in the Soviet publication Moda, 1967.

Anna Andreeva with Tatiana Andreeva, Exercise with Circles and Rhombus, 1979. Courtesy of the Estate of Anna Andreeva & Layr, Vienna. Photo: Power Station of Art.

In the photo: artists A. Andreeva (left), G. Zavgorodnaia, A. Glotova and N. Zhovtis are pleased that their designs for the competition have been printed on fabric. Photograph and caption published in Chelnok, April 13, 1960.

Anna Andreeva, printed fabric, 1960s, incorporating her half-moon designs as well as her cybernetic or mathematical stepped patterns. Courtesy the Estate of Anna Andreeva & Layr, Vienna.

Anna Andreeva, fabric, printed 1970, with circular pattern. Courtesy the estate of Anna Andreeva & Layr, Vienna.

Anna Andreeva, sketch from the series “Comets,” circa 1961–62. Courtesy the Estate of Anna Andreeva & Layr, Vienna.

Liubov’ Popova, Printed Constructivist fabric, 1923-24.

Aleksandr Rodchenko, Photograph of Varvara Stepanova at her desk, 1924. She is wearing a fabric design by Liubov’ Popova.

Anna Andreeva’s designs “Ladoga” (top) and “Greetings, Moscow” (bottom) projected onto women’s fashions, in Nina Mertsalova, “Costume and Fabric,” Decorative Arts of the USSR no. 8, 1960.

Most Western commentators on Andreeva have stressed that her designs recall those of the constructivist avant-garde.32 While there are intriguing moments in her personal history that might have facilitated a knowledge of that avant-garde—whose history was largely repressed in the postwar USSR—we posit that the connection to constructivism may be more profound, and more structural, than a simple visual connection, however convincing the comparison may be.33 Constructivism had imagined a new role for artists as “artist-producers” or even “artist-engineers” within Soviet industry, using their artistic skills to improve production processes and produce new comradely objects for the new everyday life (novyi byt) under socialism.34 Stepanova and Popova famously designed fabrics in 1923–24 for the First State Cotton Printing Factory in Moscow. They were hailed as some of the most successful constructivists because their fabrics were actually mass produced, fulfilling the constructivist slogan of “art into life.” Yet they were frustrated in their stated wish to enter the work of the factory collective, create production laboratories, and participate in production decisions; instead, they sat at home in their studios designing their fabrics on their own, like traditional artists.35 This was not surprising, given that the factory had only recently been nationalized after the October Revolution of 1917 and there had not yet been time to develop the kinds of collective design processes imagined by the constructivists.

But by the time Andreeva started working at the Red Rose factory, this was exactly the preferred model of artistic labor, even if it wasn’t always successfully achieved in practice. Andreeva was a comrade among comrades in the artistic design sector, working collaboratively with other artists, participating in the artistic council and the assortment group of the textile laboratory, engaging in comradely competitions with other textile factories, producing commissions for important events in the life of the communist nation, and, beyond the factory, taking leadership roles in the Decorative Arts section of the Moscow Union of Artists (MOSSKh) for many years. As suggested by the contrast between the photographs of Stepanova alone at home at her desk and Andreeva consistently surrounded by comrades at the Red Rose factory, this was a degree of artistic participation in collective industrial processes in a planned socialist economy that the constructivists have could only dreamed of in the early revolutionary years.

Comrade Andreeva’s experiences at the Red Rose factory tie her not only to constructivist ideals, but also, in a broader sense, to Russian cosmism. Robert Bird has argued that “Marxism is fundamentally cosmist, at least in its Soviet version,” with the sober statistical approach of the planned economy always accompanied by ecstatic visions of nature, and human beings themselves, transformed and transcended through the energetic flow of collective labor.36 This transcendence was imagined in interplanetary form in the early twentieth century by cosmist philosophers and the rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, but became literalized in 1961 with Gagarin’s space flight. The cosmism of the women of the Red Rose collective, and their constructivist foremothers, differs radically from the little men in their space costumes and metal boxes. Their swatches of fabrics with frayed edges offer, instead, a sensuous poetics of material that evokes a feminine collective weaving together the threads of the universe across generations.

The term “cosmic-minded comrade” in the title of this essay is loosely borrowed from Robert Bird, who refers to Soviet writer Andrei Platonov as a “cosmist-minded comrade.” See Bird, “How to Keep Communism Aloft: Labor, Energy, and the Model Cosmos in Soviet Cinema,” e-flux journal, no. 88 (2018) →.

Details and precise dates of Andreeva’s education and work life can be found in her personal file in the archive of the Moscow Union of Artists, at the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art (RGALI), Moscow, f. 2943, op. 13, ed. khr. 38.

See the discussion of early postwar fabric designs in N. Zhovtis and S. Zaslavskaia, “Kto prav? Pis’mo khudozhnikov-tekstil’shchikov,” Dekorativnoe iskusstvo SSSR, no. 1 (1961): 8.

A. Glotova, “Novyie risunki dlia nabivnykh tkanei,” Chelnok, June 3, 1954. The weekly newspaper Chelnok was the organ of “the Party Committee, the Factory Committee, the Komsomol Committee, and the Director’s Office of the Red Rose Factory,” as stated on its masthead.

On the need to prepare for the Festival of Youth, see the caption for the photograph of Andreeva and Zhovtis in Chelnok, January 4, 1957, and the discussion in Ksenia Guseva and Aleksandra Selivanova, Tkany Moskvy (Muzei Moskvy, 2019), 139. The latter is a comprehensive catalog for an exhibition of the same name (“Textiles of Moscow”), which has inaugurated the study of postwar Soviet textiles; it has been an invaluable resource for this essay.

I. A. Alpatova, “Novoe v tkaniakh,” Dekorativnoe iskusstvo, no. 5 (1961): 9.

Alpatova writes that in some fabrics, geometric patterns can look schematic or harsh, while others can delight the eye with the clarity of contour and the sharpness of the color combinations, demonstrating that geometric patterns were not dismissed out of hand as “formalist” (the Soviet code word for modernism); see Alpatova, “Novoe v tkaniakh,” 9.

Alpatova attributed the “Ladoga” design to both Andreeva and her Red Rose colleague Natalia Zhovtis, but the original design drawing, held in the Andreeva family archive, is signed only by Andreeva; see the Andreeva collection held at the Emmanuel Layr Gallery, Vienna. Andreeva and Zhovtis collaborated frequently, and from 1960 Zhovtis held the position of “head artist” (glavnyi khudozhnik) at Red Rose, so the double attribution may reflect a collaborative creative process based on Andreeva’s original design, or even a courtesy to Zhovtis as the leader of the collective.

Alpatova likewise attributes the “Cheremushki” design to both Andreeva and Zhovtis, although, as with “Ladoga,” the design drawing appears in the Andreeva archive with her sole signature and is attributed to her alone in the Textiles of Moscow catalog; see Guseva and Selivanova, Tkany Moskvy, 143, 158–59. The “Cheremushki” design had likely entered fabric production by 1961, when it was chosen to be reproduced as the background of the letter by Zhovtis and Zaslavskaia, “Kto prav?,” in Dekorativnoe iskusstvo; see the discussion of this provocative letter below.

Nina Mertsalova, “Kostium i tkan’,” Dekorativnoe iskusstvo SSSR, no. 8 (1960): 26. Mertsalova notes that “models” of this clothing—presumably one-off samples—were exhibited in the decorative arts section of the major art exhibition “Soviet Russia” in Moscow in 1960.

N. Kaplan, “Siuzhetnye risunki na tkaniakh,” Dekorativnoe iskusstvo SSSR, no. 11 (1961): 21. Kaplan attributes this fabric design to both Andreeva and Zhovtis, and names the Moscow landmarks shown on it: the Bolshoi theater and the TsUM department store; the Kremlin; the banks of the Moscow River; and new housing complexes.

The drawing is titled and dated on the back in Andreeva’s hand; see the Andreeva collection at the Emmanuel Layr Gallery, Vienna. Judging by the uniformity of her hand, it appears that Andreeva went through all her drawings at a point later in life, dating them and giving them titles from memory. It is therefore difficult to verify this information, except in cases where published or other archival sources corroborate it.

For examples of commemorative Russian scarves from the 1890s, see Tkany Moskvy, 40–41. There are numerous references to the production of commemorative scarves in Chelnok. A 1947 article discussing preparations for the eight hundredth anniversary of the city of Moscow and the thirtieth anniversary of the October Revolution discusses an Andreeva scarf design that “picturesquely resolves the theme of the abundance of our Motherland.” See A. Glotova, “Krasnorosovtsy gotoviat k 800-letiu,” Chelnok, July 14, 1947. Another Glotova article from 1954 announces that the Red Rose artists have been given the task of designing souvenir scarves depicting “the attractions and picturesque nature of the sanatoria of our country”; see Glotova, “Novyie risunki dlia nabivnykh tkanei.” The drawing for Andreeva’s Gagarin scarf design is held in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, while a test copy of the actual scarf is held in the Historical Museum, Moscow.

See “London Welcomes Major Gagarin,” The Times, July 12, 1961, 20; for more on the crowds thronging around him, see “Crowd Traps Yuri in the Jewel Tower,” Manchester Daily News, July 13, 1961, 13. Gagarin visited Manchester on July 12 at the invitation of the Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers (AUFW).

Diana Pulson, “A Very Elegant Invasion from behind the Iron Curtain,” Liverpool Daily Post, July 7, 1961.

“Russians Trade Ideas and Yuri Badges,” Manchester Daily News, July 13, 1961, 13.

The caption of the photograph identifies Andreeva and her companion Zoya Yartseva as members of the Soviet textile delegation. Yartseva worked as a textile designer at the Sverdlov silk factory in Moscow from 1934 to 1969. See her personal file in the archive of the Moscow Union of Artists, RGALI, f. 2943, op. 13, ed. khr. 38.

For a recent example of scholarship on Soviet space-themed material culture that does not include fashion or textiles, see Alexander Semenov, “The Soviet Space Euphoria,” in Retrotopia: Design for Socialist Spaces, ed. Claudia Banz (Kunstgewerbemuseum, 2023).

The term “space-race fashion” is used today primarily to describe clothing design in France and the United Kingdom, and fashion photography and journalism in the US, in the 1960s and early 1970s. See Suzanne Baldaia, “Space Age Fashion,” in Twentieth-Century American Fashion, eds. Linda Welters and Patricia A. Cunningham (Berg, 2008).

Tat’iana Strizhenova, “Tekstil’,” in Sovetskoe dekorativnoe iskusstvo 1945–1975, ed. Vladimir Tolstoy (Iskusstvo, 1989), 61.

“Khudozhniki k iubileiu,” in Moda, special issue of Zhurnal mod, Winter 1967–68, n.p. We have not yet been able to determine Chizhonkova’s first name.

On the philosophy of Russian cosmism and its continued effects in Soviet cultural production in the 1930s, see Bird, “How to Keep Communism Aloft.”

A reversible fabric produced in 1961 for women’s coats, in a pattern of ochre spots on black, was named “Comet” (kometa); see the illustration in Alpatova, “Novoe v tkaniakh,” 6. For a good selection of abstract or geometric fabrics produced by Soviet factories in the 1960s and ’70s, see Tkany Moskvy, 178–83.

The decree is discussed in T. Kornacheva, “Mastera priatnykh novinok,” Chelnok, April 13, 1961.

O. Stuzhina, untitled notice, Chelnok, July 28, 1960.

See Kornacheva, “Mastera priatnykh novinok.”

N. Zhovtis, “Priniato na otlichno,” Chelnok, February 10, 1965.

“Etogo trebuet potrebitel’,” Chelnok, March 12, 1964, 1.

“Budut novye risunki,” Chelnok, March 12, 1964.

Zhovtis and Zaslavskaia, “Kto prav?”

On the reluctance of seamstresses to work with new fabrics, see I. Makhonina, “Luchshii sud’ia—pokupatel’,” Chelnok, February 24, 1978.

See, for example, Samuel Goff, “The Soviet Textile Artist Who Wove Together Technology and the Avant-Garde,” Elephant, August 14, 2020 →.

When Andreeva attended the Textile Institute in Moscow in the late 1930s, a number of the teachers were artists and theorists who had been active in the 1920s, and would have been in a position to show students works by the constructivists, even if these works could not be taught officially as part of the school curriculum. In particular, Aleksei Fedorov-Davydov, an art historian who had been active in the Soviet art world of the 1920s and had worked with avant-garde artists, was an important mentor to Andreeva.

On the model of constructivism as an intervention into the production process itself, see Maria Gough, The Artist as Producer: Russian Constructivism in Revolution (University of California Press, 2005); on Constructivism as dedicated to the production of new objects for the new everyday life, see Christina Kiaer, Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism (MIT Press, 2005).

The literature on Stepanova’s and Popova’s textile design work is extensive; see for example Iuliia Tulovskaia, “Risunki dlia tkani khudozhnikov avangarda,” in Tkany Moskvy, 70–79; and Christina Kiaer, “The Russian Constructivist Flapper Dress,” chap. 2 in Imagine No Possessions.

According to Bird, “There is, Platonov suggests, the possibility of a different economy, one yet to be defined, let alone achieved, where natural limitations like gravity, entropy, and perhaps even death will not have to be resisted so forcefully, where the flight of socialism will become effortless, free, and final. This would be communism, albeit in a version that owes as much to the cosmism of Nikolai Fedorov and Aleksandr Bogdanov as it does to Marx and Lenin.” Bird, “How to Keep Communism Aloft.”