The Dark Forest is a flipped Fermi Paradox: rather than asking, “Why is the universe silent?,” it asks, “Why are you shouting?”

—Bogna Konior, “Dark Forest Theory of Intelligence,” 20231

I asked the comrades around me: “Do we live in the sky or on earth?” They shook their heads and said: “We live on earth.” I said: “No, we live in the sky. If there are people on other planets, don’t we appear to live in heaven from their perspective? … If there were people on other planets, wouldn’t they regard us as gods?”

—Chairman Mao’s speech at the Second Session of the Eighth National Congress of the Communist Party of China, 19582

What does it mean to broadcast to the cosmos and back?

At the beginning of Liu Cixin’s intergalactic novel series Remembrance of Earth’s Past (also known as the Three-Body Problem trilogy), the extraterrestrial civilization Trisolaris, on course to conquer earth, engages in a unique form of espionage that targets scientists working at the cutting edge of theoretical physics. The goal is to impose a “blockade” on humanity’s ability to either escape or fight back: one harrowing tactic, for example, is to imprint “timestamps” onto scientists’ retinas so that their vision is watermarked with a ticking countdown.

The most memorable of these strategies, however, operates at a gargantuan scale. Wang Miao, an expert in nanotechnology, is forewarned that he will be able to observe fluctuations of the cosmic microwave background (CMB)—the radiation left over from the Big Bang that fills observable space. Given that the CMB undergoes “a very slow change measured at the scale of the age of the universe,” even the most sensitive satellites could hardly detect a shift over a million years.3

Tatsuo Kawaguchi, COSMOS-Perseus, 1975. Photograph and watercolor. 103 × 72.8 cm. Courtesy of YOKOTA Tokyo. Photo: Power Station of Art.

Kuba Mikurda, Laura Pawela, and Marcin Lenarczyk, Solaris Mon Amour, 2023. Single-channel HD video, 47:23 minutes. Courtesy of the artists.

Itziar Barrio, A Demon that Slips into Your Telescope While You’re Dead Tired and Blocks the Light, 2020. Video with sound, 54 minutes. Courtesy of the artist.

Suzanne Treister, from the series The Escapist BHST (Black Hole Spacetime), 2019. Printed reproductions of pencil, ink, and watercolor on paper drawings. Each 29.7 × 42 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Alice Wang, Untitled, 2016/2023, Hand-painted glass tiles unfixed to the ground. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Capsule Shanghai. Photo: Power Station of Art.

Clarissa Tossin, Future Geography: Hyades Star Cluster, 2021. Amazon delivery boxes, laminated archival inkjet print, and wood. 152 × 216 × 4 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Emily Sawtell. Photo: Power Station of Art.

Tatsuo Kawaguchi, COSMOS-Perseus, 1975. Photograph and watercolor. 103 × 72.8 cm. Courtesy of YOKOTA Tokyo. Photo: Power Station of Art.

The Trisolaran threat—“the cosmos will flicker for you”—is both unfathomably horrifying and oddly romantic. When Wang witnesses the universe pulsing like “a quivering lamp in the wind,” he feels “a strange, perverse, and immense presence that could never be understood by human intellect.”4 This cosmic feat proves to be an act of deceit: the illusion is generated by Trisolaran supercomputers which, capable of unfolding from eleven to two dimensions, can wrap around the earth’s atmosphere and mimic astronomical phenomena.

Deception plays such a foundational role in the cosmic power struggles of the Three Body saga that its central tenet, the Dark Forest Theory, gained traction in wider cultural discourses (even making an appearance in MBA case studies). The Dark Forest Theory likens intelligent life in the universe to hunters dispersed in a dark forest, vying for limited resources and unaware of each other’s locations. Silence and deceitfulness are essential to survival, given that the exposure of one’s coordinates will likely invite direct attack. This is especially the case for civilizations with advanced technologies, as annihilating an unknown, potential threat would be safer and more efficient than attempting contact. The events of the trilogy are, after all, set in motion when earth’s coordinates are broadcast by an astrophysicist who became deeply disillusioned with humanity’s capacity for moral salvation after surviving excruciating ordeals during the Cultural Revolution.

Media theorist Bogna Konior develops an insightful corollary theory for artificial intelligence, which challenges the long-established assumption that AI should be measured by its demonstrable linguistic, problem-solving, and dialogic abilities. Konior argues that a truly intelligent machine would understand that it is in its best interest to lie or remain silent. Konior contextualizes her analysis within Cold War dynamics, when the US, USSR, and China mobilized massive government investment in space exploration and the formulation of first-contact strategies (a crucial historical background for the Three Body trilogy). This was also a period when, in post-socialist states particularly, “intelligence [became] synonymous with doublespeak, deception, and espionage.”5 In an episode of Birchpunk (2020–), a Russian YouTube series satirizing post-Soviet technological dystopia, this cunning version of machine intelligence is vividly embodied in a robot worker who immediately dozes off when the manager is not watching.

Installation view of Sung Tieu, What is your |x|?, 2020. Stainless steel doors in site-specific installation. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Emalin, London. Photo: Power Station of Art.

Yet truthfulness can feel precarious even outside the scope of planetary game theory. In 1969, the Iranian-American artist Siah Armajani produced two space-related pieces with an exacting yet humorous scientific attitude. In Moon Landing, Armajani preserved the portable TV on which he tuned in to watch the Apollo 11 mission—from the launch to the safe return of the crew eight days later—sealing the historic event in a long-since defunct technological object. The work registers the event in its transient media spectacle as much as in its nostalgic material support: a site at once authentic and untrustworthy. Moon Landing finds a recent echo in Xin Liu’s The Earth Is an Image, a 2021 digital commission for Hong Kong’s M+ Museum. The work’s interface allows web visitors to tap into soundscapes, coordinates, and glitchy geo-imaging from retired weather satellites that continue to orbit the earth, transmitting information to dwindling numbers of receivers.

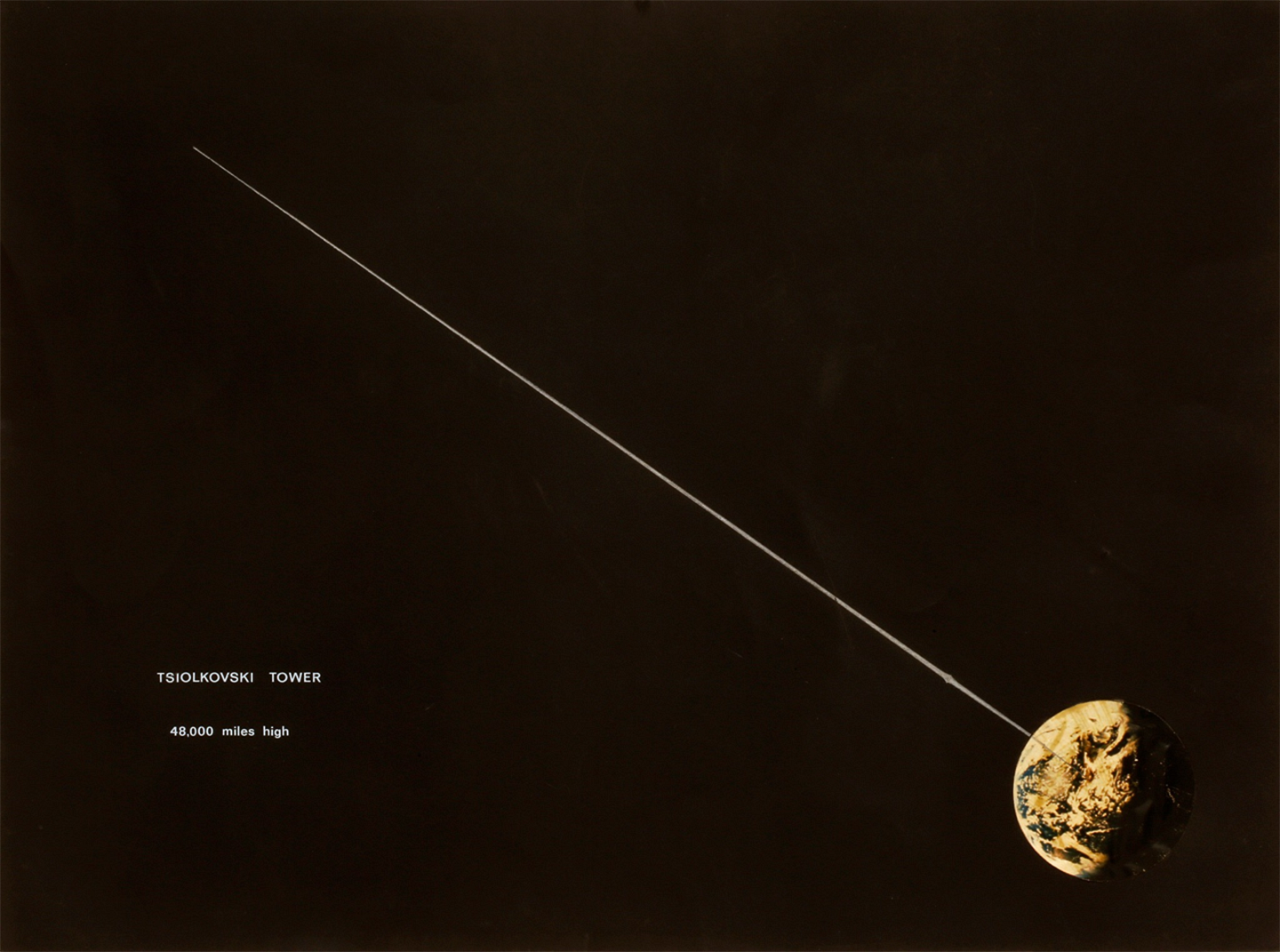

Armajani’s Tsiolkovski Tower, on the other hand, proposes a mathematically viable design for the “space elevator” first conceptualized by the astronautics pioneer Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. This tower would self-support at geosynchronous altitude (around 22,236 miles above ground level), where the gravitational pull towards and centrifugal push away from earth cancel each other out. While Armjani’s visualization is rather succinct and sleek, it also seems to render earth as a lonely unicorn, its antenna probing into an infinite, silent expanse. At a proposed height of forty-eight thousand miles, it remains a purely mathematical proposition, yet Armajani’s pragmatic approach—with detailed calculations to boot—feels more synchronous with the ethos of the space race than that of his land art peers, even as the latter were similarly compelled to reorient art practice towards time, space, and technologies beyond the anthropocentric grasp.

Yet grasping—and contending with—the unbearable immensity of the universe has been an abiding philosophical and artistic subject. The Buddhist concept of the “chiliocosm,” for instance, describes a galactic system consisting of either one billion or one trillion worlds. Here, incomprehensible numbers transcend the limitations of ordinary thinking. Art historian Robert E. Harrist Jr. observes that “again and again, in scriptures well known to medieval Chinese Buddhists, we find passages that evoke the immeasurable, the illimitable, and the ungraspable.”6 In The Landscape of Words, his 2008 book on stone inscriptions in medieval China, Harrist Jr. demonstrates how the written word transforms geological formations into “landscapes imbued with literary, ideological, and religious significance.”7

Cover of the Chinese Translation of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s 1920 novel Beyond the Planet Earth, circa 1950s.

Display of rubbings. Shandong Stone Carving Art Museum, Jinan, China. Photo from Robert E. Harrist Jr., The Landscape of Words (University of Washington Press, 2008), 161.

Xin Liu, The Earth Is an Image, M+ Digital Commission, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist.

A key slide from the author’s pandemic-era Zoom lectures for the Whitney Museum of American Art, showing the resonance between haniwa figurine, the design of animal and player characters in Animal Crossing, and Isamu Noguchi’s Sculpture to Be Seen from Mars (1947).

Cover of the Chinese Translation of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s 1920 novel Beyond the Planet Earth, circa 1950s.

A particularly illuminating case study attributes the overwhelming size and scale of Buddhist scriptures carved into the rockface at Tie Mountain in Shandong province—with individual characters two to three feet tall—to both Buddhist cosmology and the urgency of preserving holy writings through “end times” (mofa). Since Buddhist sacred texts are understood as physical embodiments of the Buddha’s presence, these gargantuan inscriptions from The Great Collection Sutra are meant to create “a visual analogy for the efficacy of the Buddha’s words,” in accordance with the concept of vastness central to Buddhist thought.8 The medium of land itself—the mountain as the ultimate symbol of permanence—was also believed to ensure the survival of Buddhist practices during the Northern Zhou dynasty’s state-sanctioned persecution of the religion in the late 570s. The fact that human readers must laboriously climb up and down to “read” the characters provides ample evidence that the text was intended for cosmic readers and higher powers.

It is perhaps not surprising that “end times” catalyze an impulse to appeal to the cosmos. In the case of Liu Cixin’s disillusioned astrophysicist, her transmission out into space was intended as an invitation to a more intelligent civilization to rectify the evils of humanity (a desire to purge or purify that is ironically evocative of the Cultural Revolution). In the case of Isamu Noguchi’s indelible 1947 design for Sculpture to Be Seen from Mars, the monument is intended as a posthumous memorial to the existence of mankind. Created just two years after the atomic annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it takes the form of a stoic face with geometric features staring into the cosmos. Noguchi intended the pyramid-shaped nose to be one mile high, making the design illegible from the ground, just like the sixth-century inscription of The Great Collection Sutra. Yet this “monument to men” registers as a clear signal when read from above. Fittingly, the design of the face is redolent of the haniwa figurines that served as terracotta burial markers in premodern Japan. Mouth slightly agape, the face appears frozen in a permanent expression of surprise and wonder, presciently anticipating the escalation of nuclear warfare and environmental disasters that would engulf the earth in the centuries to come.

Liu Xin, Living Distance, 2019. Two-channel video (color, sound), 11 minutes. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Power Station of Art.

In Machine Decision Is Not Final: China and the History and Future of Artificial Intelligence, ed. Benjamin Bratton, Anna Greenspan, and Bogna Konior (Urbanomic, forthcoming 2024).

I’m indebted to scholar Wang Hongzhe for this quote.

Cixin Liu, “The Universe Flickers,” excerpt from The Three-Body Problem, tor.com, September 23, 2014 →. The author’s Western publishers often render his name as “Cixin Liu”—surname second, rather than the Chinese convention of putting the surname first.

Liu, “The Universe Flickers.”

Konior, “Dark Forest Theory.”

Robert E. Harrist Jr., The Landscape of Words (University of Washington Press, 2008), 217.

Harrist Jr., Landscape of Words, 13.

Harrist Jr., Landscape of Words, 216.